Japanese Women’s Colleges Hang Hopes on STEM Ed: Lessons from America’s Seven Sisters

Society Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Women’s Education at a Crossroads

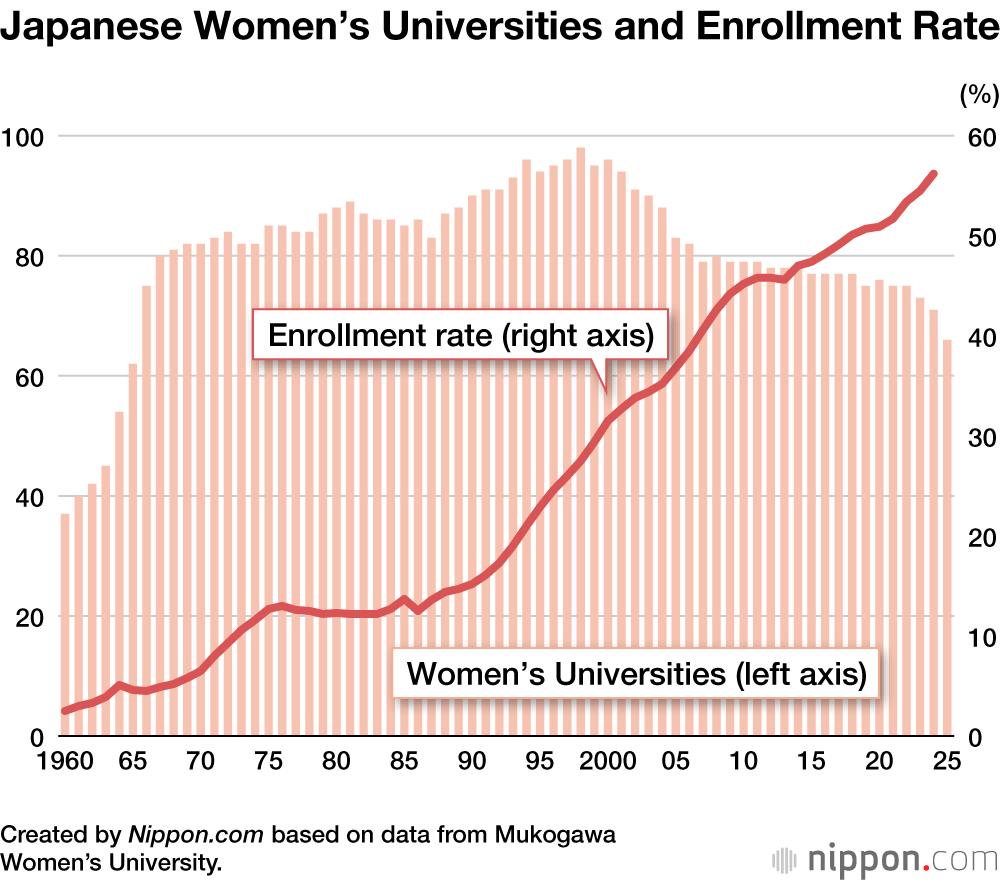

The percentage of Japanese women enrolling in four-year universities has continued to climb over the past quarter century, yet the number of women’s universities has dived over the same period. As of 2025, Japan had just 66 four-year women’s colleges, down more than 30% from the 1998 peak of 98. Of the women’s universities operating in 2025, a full 70% were under-enrolled.

A good portion of these schools seem doomed to succumb, either by opening their doors to male students or by closing them altogether. But others, inspired by the example of a few elite US institutions, are rolling out new educational programs devoted to training female scientists, engineers, and IT professionals. Will their gamble pay off?

Historical Context

Prior to World War II, single-sex education was the rule in Japan. In 1875, the government established the country’s first post-secondary educational institution for women, Tokyo Women’s Higher Normal School (later to become Ochanomizu University), for the purpose of training female teachers. Nara Women’s Higher Normal School (today’s Nara Women’s University) was founded for the same purpose in 1908. The first private women’s colleges were Tsuda University, which opened in 1900, and Japan Women’s University, founded in 1901.

The postwar education reforms forced other universities to open their doors to women. Yet for many years, two-year junior colleges (instituted in 1950) were the choice of most women who continued their education past high school. The main reason was that Japanese corporations typically hired their female support staff from the graduating classes of these women’s colleges. Placed on a non-career track known as ippanshoku, female employees were expected to leave the labor force as soon as they married. At junior colleges, accordingly, the educational focus was on nurturing “good wives and wise mothers.”

This system began to come under pressure after the passage of the 1985 Equal Employment Opportunity Act. With companies abandoning blatantly gender-based hiring and assessment, women’s educational needs shifted accordingly.

In 1985, only 13% of female high school graduates went on to four-year universities, as compared with 35% of men. By 1996, the university enrollment rate for women had climbed above 20%, surpassing the ratio for junior colleges. As of 2024, the university enrollment rate for women was 56.2%, as compared with 61.9% for men.

But women’s universities have struggled during the same period. The decline of single-sex education at the primary and secondary levels was a factor, along with the passage of equal opportunity legislation. In addition, many women’s colleges have found themselves unable to meet growing student demand for an education in such traditionally male-dominated fields as economics, business, science, and engineering.

Lessons from the Seven Sisters

Women’s colleges in the United States have also been under pressure to admit male students, and many have succumbed. But of the so-called Seven Sisters—a group of prestigious, historically female private colleges located in the Northeast—five have bucked the trend while exploring new horizons in women’s higher education. Japan has much to learn from these American efforts to update and rebrand women’s colleges.

Amid the rise of feminism in the 1960s and early 1970s, gender-separated schooling was increasingly perceived as discriminatory, just as the Civil Rights movement had discredited the notion of a “separate but equal” education. When America’s all-male Ivy League schools started going coed during this period, they triggered an exodus from the Seven Sisters and other top women’s colleges. Between closures and mergers, the number of all-women’s colleges in the United States plunged from 230 in 1960 to 35 in 2023.

With more and more top-tier female students choosing the Ivy League schools, the Seven Sisters responded to the crisis in different ways. Vassar College (Poughkeepsie, New York) went coeducational on its own in 1969 after rejecting a proposal to merge with Yale University. Vassar’s Board of Trustees was unwilling to see their own school’s educational tradition and identity subsumed by Yale’s—which, in fact, is what happened to another Seven Sisters school, Radcliffe College (Cambridge, Massachusetts), as a result of its gradual integration with Harvard University. Radcliffe has ceased to function as a college and now exists only as the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard.

Vassar, on the other hand, chose to go coed while preserving its educational integrity, particularly its longstanding emphasis on small classes. In its 2026 ranking of American colleges and universities, US News and World Report ranked Vassar number 13 in the category of liberal arts colleges.

The remaining five “sisters” have chosen to preserve their all-women status. They include Wellesley College (Wellesley, Massachusetts), the alma mater of former Secretaries of State Hillary Clinton and Madeleine Albright, and Bryn Mawr College (Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania), where Tsuda Umeko, the founder of Tsuda University, pursued her studies. They are part of a movement to redefine such institutions as “laboratories” where women can develop their leadership without deferring to men.

In 2015, Wellesley launched a massive, high-profile fundraising campaign extolling the so-called Wellesley Effect—that is, the positive and lasting impact of a Wellesley education on women and, by extension, on society as a whole. The campaign surpassed its $500 million goal, the largest fundraising target in the history of women’s colleges.

Iino Masako, former president of Tsuda University, once related the following observation from Drew Gilpin Faust, the first female president of Harvard University (2007–18). According to Iino, Faust told her that Wellesley had given her the confidence to do anything she set her mind to. Faust maintained that had she studied at Harvard, she would have felt too intimidated to develop her full potential. At women’s colleges and universities, women play a leading teaching and administrative role. This helps create an environment that gives women students the confidence to express themselves freely. By nurturing self-esteem in this way, women’s colleges serve as incubators for female leadership.

America’s Strong Track Record

Smith College (Northampton, Massachusetts) has also worked hard to preserve its all-women status by rebranding. In 1999, Smith became the first US women’s college with an accredited engineering program. Its first class of engineers graduated in 2004. A $73 million science and engineering facility, christened Ford Hall, was completed in 2009 with the aid of generous grants from the Ford Motor Co. Over the past 25 years, Smith College has trained hundreds of graduates in the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields.

The 2023 report “Why You Should Consider Applying to an All-Women’s College,” published by the college planning consultancy Top Tier Admissions, provided quantitative data comparing women’s college alumnae with female graduates of coeducational schools. It reported that women’s-college graduates were more likely to be employed in STEM fields than coeducational-school alumnae, by a margin of 37% to 29%. It also found that the proportion of women rising to senior management positions within a decade of graduation was 23% for women’s-college graduates, as compared with 19% for coed-school alumnae.

These statistics suggest that, far from being a relic of the past, America’s top women’s colleges are flourishing, having rebranded themselves as places where women can go for a premium educational experience leading to career opportunities.

Merits of an All-Women Learning Environment

It has been 40 years since the enactment of Japan’s Equal Employment Opportunity Act. Yet in 2025, the World Economic Forum ranked Japan 118 out of 148 countries in its Global Gender Gap index, far below the other Group of Seven countries.

Tsuda University President Takahashi Yūko, an expert in gender studies, had this to say in her April 2025 entrance ceremony address: “Living each day in an environment where everything revolves around women is an experience you will never have again after you enter society. Here, it seems perfectly natural for women to be central and to show their full potential. That creates the conditions for self-affirmation, higher expectations of oneself, and greater self-esteem.”

Of course, some will question the point of studying in an all-female environment at a time when women are competing head to head with men on the labor market. But Professor Nagata Junko of Osaka Metropolitan University, citing her own experience with corporate training programs, argues that “female-only learning spaces are all the more important now that gender equality is an issue.” When women trained alongside men, she notes, the results were disappointing, but when they were placed in a women-only management training program, they flourished. “Whether in a corporate or academic environment, women often do better in a female-only learning space.”

Riding the IT and Engineering Wave

Over the past few years, Japanese women’s colleges have also begun shifting their academic focus to STEM disciplines and launching new faculties dedicated to engineering and computer science.

In the field of engineering, Nara Women’s University established Japan’s first women-only faculty of engineering in 2022. Ochanomizu University made the leap in 2024, when it opened its Faculty of Transdisciplinary Engineering. That same year, Japan Women’s University upgraded its Department of Housing and Architecture to Japan’s first women’s Faculty of Architecture and Design.

In 2023, meanwhile, Kyoto Women’s University launched Japan’s first Faculty of Data Science for women. Ōtsuma Women’s University followed in 2025. Shōwa Women’s University’s Faculty of Information Science is scheduled to open in April 2026, and Tsuda University plans to establish a (tentatively named) Faculty of International Math and Computer Science in 2028. Anticipating the migration of students from the social sciences and humanities, most of these schools are highlighting an integrated, multidisciplinary approach.

This shift toward the STEM disciplines may pay off in Japan, as it has in the United States. Still, there are concerns. The proliferation of data science programs seems a bit excessive, notwithstanding the field’s gender imbalance. Opportunities for women in science and engineering are expanding at coeducational universities as well, with a growing number of institutions setting admissions quotas for female applicants to STEM programs. Under the circumstances, the women’s universities could have their work cut out competing for science and engineering majors.

A Path to Survival?

Education journalist Gotō Takeo is optimistic, however. “At coeducational universities, male students completely dominate the science and engineering faculties, which can create an uncomfortable learning environment for female students. That’s not an issue at women’s universities, so they should find it easy to attract applicants.” Furthermore, with a growing number of students at all-girls high schools choosing the math and science track, Gotō believes that “the shift toward science and engineering offers a path to survival for women’s universities.”

Japanese women’s universities that decide to admit men should probably follow Vassar’s example and develop a strategy that allows them to maintain their traditional strengths even while capitalizing on the merits of a mixed-gender environment. Women’s schools that simply go coed in a desperate bid to attract qualified applicants are unlikely to survive over the long term.

The future of Japan’s women’s universities, like that of their American counterparts, will hinge on their ability to successfully rebrand while raising awareness of their unique and enduring contribution to society.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Tsuda University, a private women’s college based in Kodaira, Tokyo. Established in 1900, it is one of most prestigious higher educational institutions for women in Japan. © Pixta.)