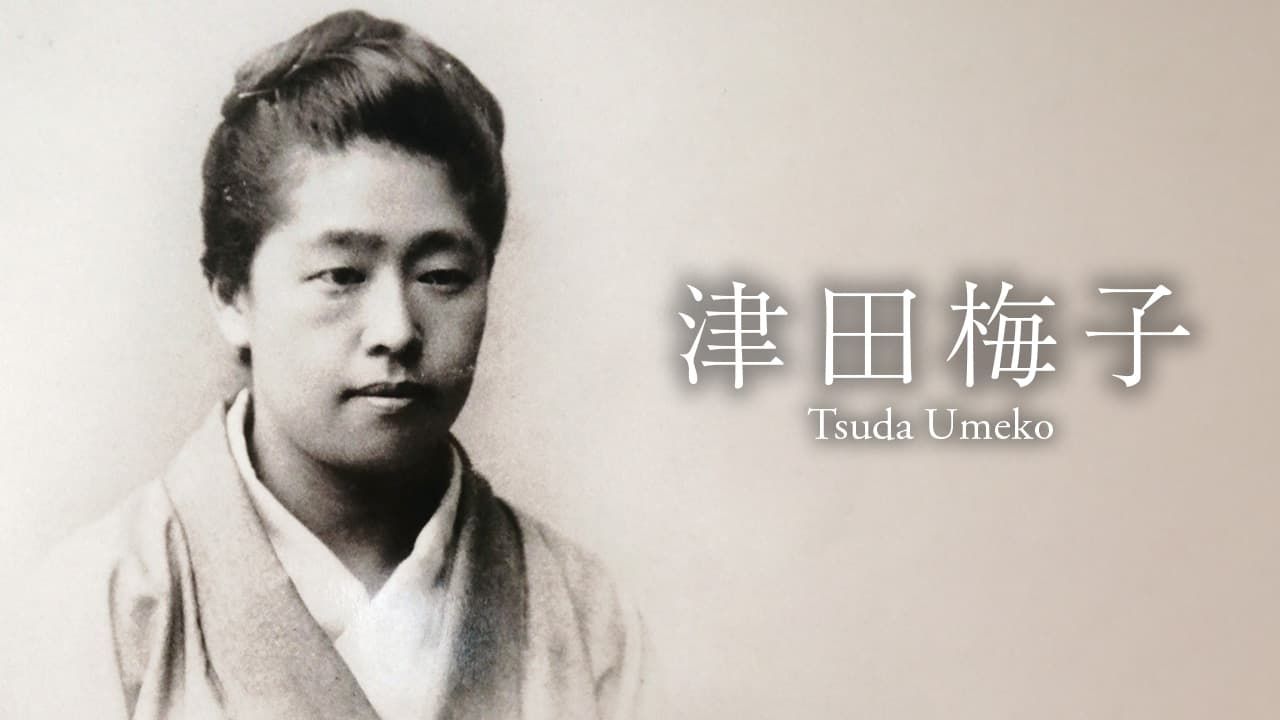

Tsuda Umeko: A Life Dedicated to Women’s Higher Education

Society Culture Education History Gender and Sex- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Childhood Spent Studying in the United States

Tsuda Umeko was born in Edo (now Tokyo) in 1864, the daughter of agriculturalist Tsuda Sen and his wife Hatsuko. In 1871, she traveled to the United States with the Iwakura Mission, becoming one of the first female Japanese overseas students. As she was just six years old, her father no doubt played a major role in the decision. Sen was a long-term acquaintance of Kuroda Kiyotaka, director of the Hokkaidō Colonization Office, who believed in the importance of women’s education, and who petitioned the government to allow women to study abroad. It was Kuroda who recommended Sen and Hatsuko’s daughter as a candidate student. Sen himself had studied in the United States at the end of the Edo period (1603–1868), and believed that Japan should look to America to catch up with the West. It seems likely that he impressed this outlook onto his daughter.

Tsuda settled in Washington, D.C. with the secretary to the Japanese legation, Charles Lanman, and his wife Adeline, where she entered school. Through her efforts, she mastered English and other basic subjects. During her time in the United States, Tsuda converted to Christianity and was baptized. Although she hoped to enter university, after 10 years abroad, and facing financial pressure, she opted to return to Japan.

The delegation of female Japanese students, photographed at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, 1876. From left to right, Tsuda Umeko, Yamakawa Sutematsu, Nagai Shigeko. (Courtesy Tsuda University; © Jiji)

While in Washington D.C., Tsuda had a significant meeting with Mori Arinori, who went on to become Japan’s first minister of education. No doubt she was influenced by his belief in Japan’s need to expand education in order to modernize, and she received support from him both directly and indirectly when she became an educator after returning to Japan.

Different Paths

Although Tsuda had mastered the English language, upon returning Japan, she struggled to find employment commensurate with her abilities. At best, she was hired as a part-time English teacher at a girls’ school, then employed as a tutor to the daughters of Itō Hirobumi, who she no doubt met on the Iwakura Mission, and who went on to become Japan’s first prime minister.

It is worth noting that Tsuda had some involvement in the world of politics through Itō. In those days, it was common for politicians to use the services of geisha, and she was dismayed at witnessing men treat women as playthings. She lost her trust in men, and this was perhaps one reason why she remained single throughout her life.

Tsuda came to believe that not being able to attend university had prevented her from advancing to a professional career. Ōyama (née Yamakawa) Sutematsu and Uryū (née Nagai) Shigeko, her fellow students on the Iwakura Mission, both undertook university studies in the United States, no doubt leaving Tsuda wishing she had too. The three became close friends, helping one another after their return, despite some rivalry between them.

Interestingly, the three took very different paths later in life. Sutematsu married army leader Ōyama Iwao and became a housewife, while Shigeko married naval commander Uryū Sotokichi, and continued working while she raised their children. Of the three, only Tsuda remained single, and spent her life as a career woman. The patterns of their respective lives can still be seen reflected in the lives of educated women in contemporary Japan.

Studies in Biology

Disenchanted with prospects in Japan, Tsuda returned to the United States on her own to realize her dream of university education. The Peeresses’ School (now Gakushūin), her employer at the time, allowed her to divert her income towards her study abroad, and she also received a partial scholarship at Bryn Mawr College, in Philadelphia. As in Japan at the time, higher education for women and men in the United States was segregated, and Bryn Mawr was one of the so-called Seven Sisters group of elite women’s colleges. Tsuda lived in the university dormitory, received a rigorous education, and graduated with flying colors.

It is noteworthy that, while she majored in education and English, she also followed in her father’s footsteps in studying biology. She even cowrote papers with her adviser, Dr. Thomas H. Morgan, a prominent academic who went on to receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933. Had Tsuda continued her studies to postgraduate level, she might have led a very different life. Instead, she chose to return to Japan.

A University for Women

Tsuda returned to Japan in 1892, aged 28. She resumed her post teaching English at the Peeresses’ School, with a growing desire to found a school based on her ideals. At the time, the only higher educational institution for women in Japan was Tokyo Women’s Normal School (now Ochanomizu University), a national university. Tsuda hoped to found a private women’s university, but faced many hurdles to achieving this.

Her greatest obstacle was securing funding, as she was hampered by her low earning capacity as a woman. Around this time, Naruse Jinzō founded Japan Women’s University, thanks to funding he secured through the assistance of political and industrial giants such as Itō Hirobumi, Ōkuma Shigenobu, and Shibusawa Eiichi. However, it was not as easy for Tsuda to attract financial support. The best she could do was gather smaller donations from the United States through her church connections.

The second challenge she faced was the lack of demand for women’s education and difficulties in attracting potential students. Tsuda eventually managed to entice 10 graduates of church-operated mission schools for her school when it opened.

A third hurdle to realizing her dream was the difficulty in finding capable teachers due to the lack of educational institutions for women. Tsuda again used her connections to arrange to hire American educators including Alice Bacon and Anna Hartshorne.

After overcoming these and other obstacles, Tsuda finally opened Joshi Eigaku Juku in 1900 in a refurbished house in Kōjimachi, Tokyo. The school underwent repeated remodeling before relocating to the site of the Seishū Jogakkō three years later, thanks to the generosity of American donors. It was here that it finally took on the appearance of a real school.

The school’s main focus was English language studies, and the students excelled under the passionate training of Tsuda and the other faculty. In 1903, the Ministry of Education reorganized post-secondary schools into senmon gakkō (professional schools), and Joshi Eigaku Juku was approved as one of them. The school earned such a reputation for its teaching that graduates were exempted from the government examination for the English teaching certificate.

Tsuda’s Legacy

At the age of 53, Tsuda fell ill, which forced her to retire from her post of 20 years as the school principal two years later. Following her retirement, she continued to battle illness for many years. After she passed away in 1929, aged 64, the school was renamed Tsuda Eigaku Juku in her honor.

Tsuda University, as it is now known, remains a prominent force in women’s education in Japan. Although the university previously taught home economics, as was common at women’s schools, it has since done away with this. Today, it is a unique institution specializing in teaching and research in education studies and liberal arts, particularly English.

Tsuda Umeko remained single in a society where over 90% of the population got married. Her biographies show fleeting attractions to men. She was also encouraged to marry by those close to her, and was introduced to prospective partners, yet she chose to remain single. She may have believed that this way of life, unburdened by the responsibility of caring for a family, was best suited for achieving her dream of establishing an institution for women’s English-language higher education.

The new ¥5,000 note featuring a portrait of Tsuda Umeko, which is due to go into circulation in 2024. (Courtesy the Ministry of Finance; © Jiji)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Portrait of Tsuda Umeko. Courtesy Tsuda University; © Jiji.)