“Tengu”: The Birdlike Demons that Became Almost Divine

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Probably just about everyone in Japan knows what a tengu looks like—but unlike kappa, these long-nosed goblins have never made the transition into cute and cuddly popular characters. Tengu have a more forbidding appearance. Closely linked with the mountainous ascetic practices of the syncretic shugendō religion, they are often regarded as semi-divine creatures. Perhaps this is part of the reason why they have not found the same place in people’s hearts as kappa and many other yōkai. There is something intimidating about them.

They also have an image problem. Blame it on the nose.

The protuberant noses that are the tengu’s most obvious features are commonly understood as symbolic of a haughty attitude of snooty self-satisfaction. When someone in the public eye experiences a surge in popularity, it is common to hear other people muttering disapprovingly: “He’s turned into a real tengu recently.” It’s a common expression in Japan: to “act like a tengu” means to be conceited or arrogant.

In Demon Slayer, Urokodaki Sakonji, the master swordsman who instructs the hero Kamado Tanjirō, always wears a tengu mask, because he doesn’t like being teased by demons for his gentle face and good looks. In former times, if a person went missing, it was often said that the person had been “spirited away” or taken away by the gods (kamikakushi). Tengu were widely believed to be responsible for these abductions.

A tengu’s nose juts straight out from his face like Pinocchio’s. They are generally shown with red faces, and dress in the garb of yamabushi ascetic priests. They have a pair of large wings on their backs, and often hold a large, feathered fan. This is the image of tengu in most people’s minds. The prominent nose and ruddy complexion have led to a popular belief that the tengu might have been inspired by the unfamiliar appearance of the first foreigners to arrive in Japan centuries ago.

A typical tengu in the popular imagination today. (© Pixta)

Origins in China As a “Celestial Dog”

Despite the popularity of this theory, in fact the history of the big-nosed tengu is surprisingly recent. Although records of creatures called tengu can be found as far back as the seventh century, their depiction has varied dramatically over the centuries, and the image that people have of them today only became established during the Edo period (1603–1868).

Initially, the tengu was not a Japanese yōkai at all. Its origins lie in China, where the word tiangou, written with the same characters (天狗), means “celestial dog.” The creature was a kind of ill-omened comet or meteor, the roar of which as it entered the earth’s atmosphere was believed to resemble a dog’s bark. Even today, in China and Taiwan, the tiangou is commonly thought of as a canine monster.

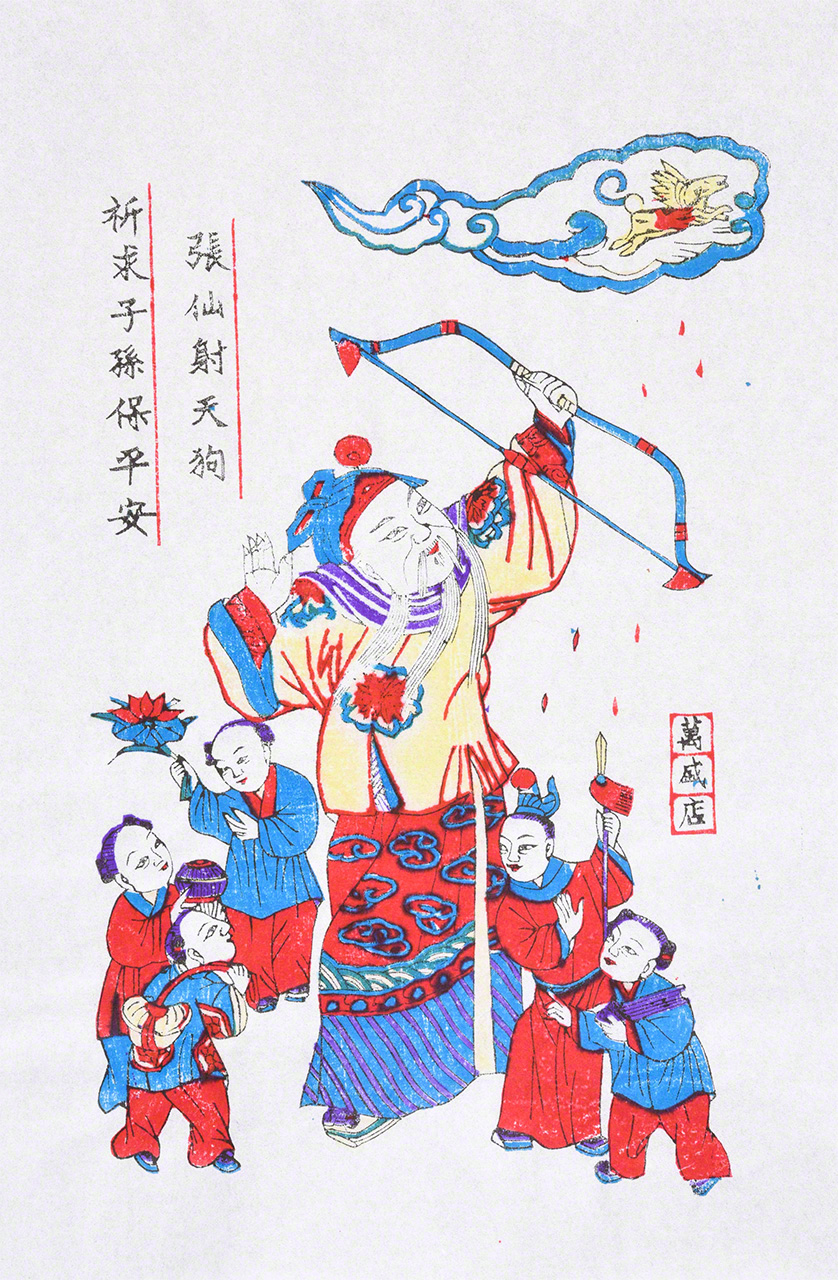

“Zhang Xian Shoots the Tiangou.” Cards like this would be hung in houses to ward off bad luck at Chinese New Year. Zhang Xian, the guardian deity of children, protects his charges from illness by shooting the ill-omened tiangou. (Courtesy Kagawa Masanobu)

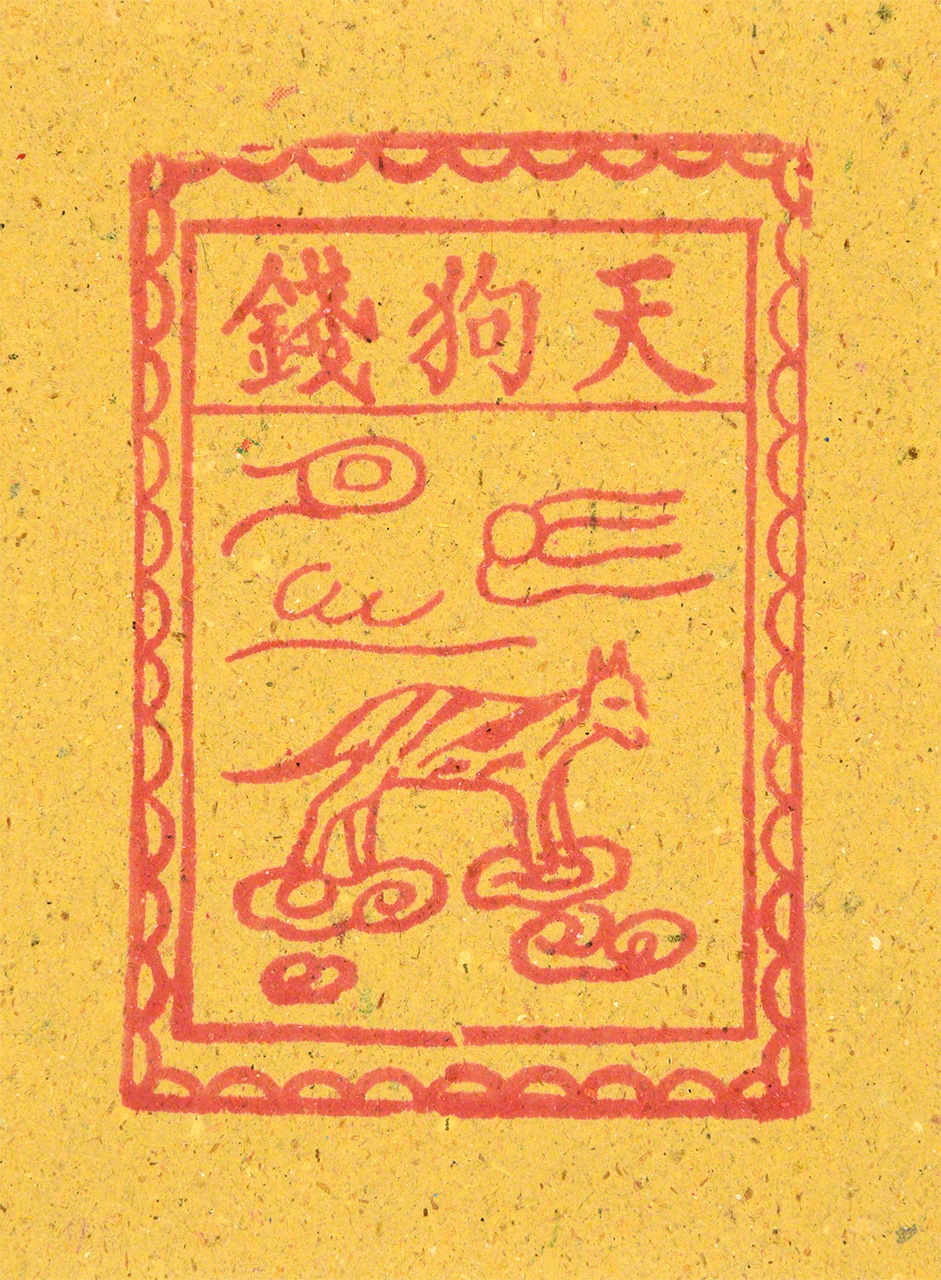

In China and Taiwan, people would pay Taoist priests to burn joss paper printed with images of the tiangou to ward off evil and ill omens. (Courtesy Kagawa Masanobu)

Japanese Versions of the Legend: The Evolution from Fox to Bird

Legends of the tengu arrived in Japan around the seventh century. According to the Nihon Shoki (Chronicle of Japan), in the second month of the year 637, a great star was seen in the sky, moving from east to west, and a rumbling noise was heard like the sound of thunder. Noticing the strange celestial occurrence, a Buddhist monk named Min observed that this was no ordinary shooting star. Min had studied in China on one of the Japanese missions to the country, and his observation must have been based on knowledge he had acquired about Chinese legends of the tiangou.

In China, the appearance of a tiangou was taken as an omen of war. And sure enough: in the Nihon Shoki, the section following this account tells of an uprising of the unruly Ezo tribes of eastern Japan. Even so, the association of tiangou/tengu with shooting stars and meteorites never become firmly established in Japan. Instead, the Nihon Shoki glosses the Chinese characters 天狗 as “amatsu kitsune” or “celestial fox.” From around the tenth century, during the Heian Period (794–1185), there was a belief that tengu, like foxes, had the ability to bewitch people. The Tale of Genji, written in the eleventh century, mentions the “tengu” as a fearsome goblin-like yōkai that tricks and abducts people.

In the later Heian Period and into the Middle Ages, the association of the tengu with the skies saw them increasingly depicted as having a birdlike appearance. Often, they were imagined as looking like black kites (tobi) and other birds of prey. Tengu make frequent appearance in the Konjaku monogatari, a collection of tales compiled in the first half of the twelfth century, where they are often described as resembling a buzzard.

The warrior hero Minamoto Yoshitsune spent his boyhood on Mount Kurama in Kyoto, where according to legend he was trained in the martial arts by a Great Tengu, avatar of the local Shintō deity Kibune Myōjin and his followers the Karasu-tengu or “Crow Tengu.” This ukiyoe print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi was produced around 1847–52, based on the nō play Kurama tengu. (Courtesy Kagawa Masanobu)

The Tengu that Prophesied the Fall of the Kamakura Shogunate

Around the same time that tengu acquired their avian appearance, they became associated with the demons and devils that were the sworn enemies of Buddhism. When the Buddha sat in meditation under the bodhi tree on his quest for enlightenment, demons appeared to distract him from his meditations. The tengu became thought of as connected with these mischievous demons, and it was believed that they would try to obstruct monks and lure them away from their lives of devotion.

A belief also arose that tengu were the reincarnation of bad Buddhist priests. A learned senior priest who died seething with resentment after being defeated in a struggle for power might be reborn as a tengu. As a priest was supposed to rise above mundane desires and distracting emotions, ending his life still suffering from worldly attachments was a degenerate fall from grace. Like a fallen angel, these learned priests were believed to be reborn as goblins with demonic powers.

From the fourteenth century, Japan entered a period of political instability and civil war, with authority divided between two rival courts. This period of unrest served to strengthen the view of tengu as an omen of chaos and conflict. In a sense, this marked a reversion to their original significance in Chinese legend. In the historic epic Taiheiki, several tengu appear before Hōjō no Takatoki, the last regent of the Kamakura shogunate, dancing and chanting: “How we long to see the devil star appear above Tennōji temple.” The unnatural star mentioned here is an omen of imperial disorder, and suggests that a rebellion will start from close to Tennōji that will destroy the shogunate. The connection between the tengu and a mysterious celestial body also marks a return to the Chinese version of the legends. Around this time, there was a tendency to interpret anything out of the ordinary as the work of tengu. In that sense, tengu became the best-known representatives of the uncanny world of the supernatural in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Japan.

This 1887 print by Utagawa Kunimasa depicts the famous scene in a kabuki play based on the Taiheiki, in which tengu appear before the ruler Hōjō no Takatoki to perform a dance that prophesies the ruin of his government. (Courtesy Kagawa Masanobu)

Edo Period Promotion to Quasi-Divine Status

It was during the Edo period that the popular image of the tengu changed to the one we are familiar with today. The tengu were transformed from birdlike monsters to essentially human figures with long noses. It is not clear what caused this change. One theory is that the first person to depict a tengu in something close to its modern guise was Kanō Motonobu (1476–1559), the artist who brought the Kanō school of painting to prominence. Motonobu had been commissioned to paint a tengu and was struggling to know how to depict something he’d never seen, when a strange creature appeared to him in a dream. He drew exactly what he had seen in his dream, and thus was able to fulfil his commission. Although Motonobu’s tengu still exists, there is naturally no way for us to verify the truth of this story. Characters with unnaturally long noses can be found in the dramatic and pictorial arts from long before Motonobu’s time, and the idea of a long-nosed tengu may have been inspired by these earlier models.

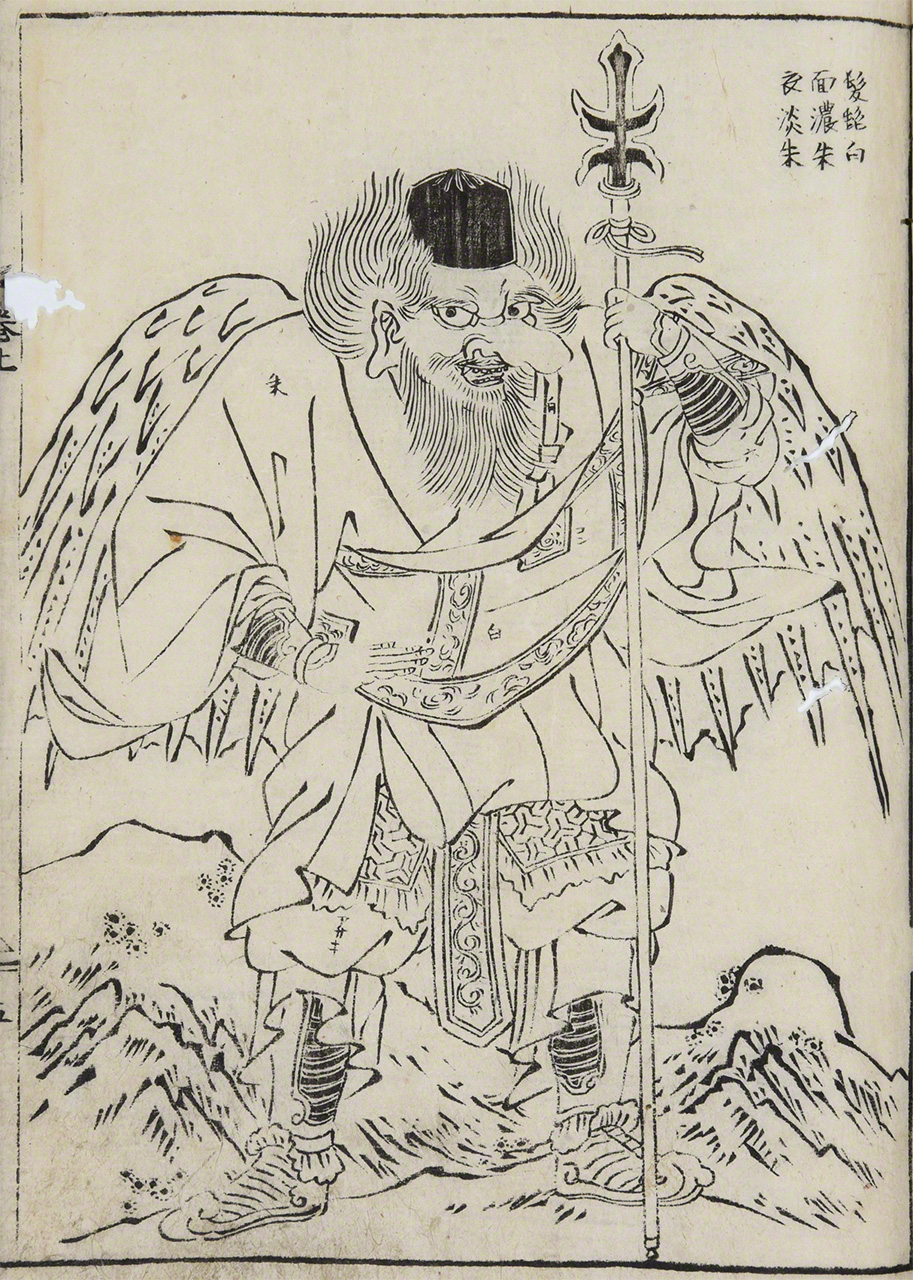

Sōjōbō, the tengu priest of Mount Kuruma in Kyoto, attributed to Kanō Motonobu. Published in the Ehon tekagami (An Illustrated Book of Model Paintings), in 1720 by Ōoka Shunboku. (Courtesy the Hyōgo Prefectural Museum of History.)

It was also during the Edo Period that the tengu achieved “promotion” from a mere yōkai to something close to divinity. Primarily regarded as a kami of the mountains, tengu were also credited with the ability to put out fires. For example, the Akiha Gongen avatar worshiped on Mount Akiha in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, is famous for its firefighting abilities. This same god, which gives its name to the famous “otaku paradise” of Akihabara in Tokyo, became closely associated with a giant tengu called Sanjakubō. The belief that tengu could prevent fires and other disasters seems to have developed as the flip side of their reputation as demon-like supernatural beings with the ability to start fires.

Talismans like this, inscribed with the image of the tutelary deity Akiha Sanjakubō Daigongen, are distributed at the festival held to honor the fire-quenching deity each January at Entsūji temple in Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture. Sanjakubō, depicted as a crow tengu standing on a fox, is often regarded as a manifestation of the Akiha Gongen deity, and these talismans are believed to have magical powers to ward off fire. (Courtesy Kagawa Masanobu)

Folklorist Yanagita Kunio believed that many yōkai are former kami that had been reduced in status after their cult lost favor for one reason or another. It is hard to apply Yanagita’s theory to what we know about tengu. If anything, these creatures enhanced their reputation over the centuries, rising from birdlike demons to something close to full-fledged kami at their peak. In the Edo period, it was common for tengu to castigate people for their arrogance, rather than being creatures that had fallen to become demons as a result of their own pride. The tengu of the Edo period, despite their big noses, were not the haughty figures they are often seen as today.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The famous tengu at Mount Kurama in Sakyō-ku, Kyoto, where Minamoto Yoshitsune was trained in swordsmanship as a boy. © Pixta.)