Photographer of the Wild North

Ōtake Hidehiro Learns More Lessons of the Life Giving Earth

Images Travel Environment Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Nature photographer Ōtake Hidehiro has spent decades capturing the Northwoods wilderness of North America. In 2021 he won the prestigious Domon Ken photography award for his work. In this series he revisits the ups and downs of his career and achievements. The Ken Domon Museum of Photography in Sakata, Yamagata Prefecture, will exhibit his work from October 6, 2021.

Previous Installments

Part 1: “Photographer Ōtake Hidehiro: Following the Dream Wolf.”

Part 2: “Photographer Ōtake Hidehiro Finds His Path Forward.”

Part 3: “Photographer Ōtake Hidehiro Heads into the Canadian Wilds.”

Part 4: “Photographer Ōtake Hidehiro Is Guided by the Blaze”

A Life of Coexistence

The Northwoods, where I chased after my dream of photographing wild wolves, is a world of trees and lakes spreading across the upper center of North America. This region was covered by glaciers some 10,000 years ago, but when the ice retreated, humans settled here to follow a life of hunting and gathering. The Ojibwe and Cree indigenous peoples of the First Nations, also called the Anishinaabe, still call the central woodlands area home.

I first felt drawn to spend more time in nature by my experiences of camping out and hiking in my university days, experiences which made me rethink issues of urban life and modernity. It seems only natural that I would be even more drawn to the lifestyles and culture of the Indigenous peoples who had coexisted with this natural environment for so long.

In the autumn of 2007, I got the chance to stay with Anishinaabe Elders at a cabin in Woodland Caribou Provincial Park. There were archaeologists there as well, finding stone tool fragments scattered nearly everywhere, driving home just how recently people had still been using them. When I took a three-week canoe trip through the Northwoods with my friend Wayne Lewis, it had felt like we were the only two people in the whole world, but I now realized that we had simply been visiting the true homeland of these people.

Pictograph along the Bloodvein River. (2010)

Protecting Ancestral Lands

The nation of Canada has signed treaties with Indigenous peoples guaranteeing them traditional hunting and land use rights. However, the truth is that those people still struggle to preserve their cultural inheritance. From the late nineteenth century well into the twentieth, the Canadian government forced Indigenous children into residential schools where their own cultures and languages were denied them. Their ancestral hunting grounds have often been designated public land and developed without the consent of the original residents. Indigenous communities and their lifestyles have also been under threat of physical harm, as seen at Grassy Narrows, Ontario, where runoff from a chemical plant poisoned the water with mercury, causing residents to suffer from Minamata disease.

Harvesting wild rice, or manoomin. (2012)

Manitoba-born Sophia Rabliauskas, who is a member of Poplar River First Nation, stepped up to help protect these lands. She compiled a land management plan map based on the actual way that villagers have used the land, showing how the forests and lakes are irreplaceable treasures for the Anishinaabe. To counter a proposed power line construction project, she and other community members pushed for UNESCO to designate the area as a World Heritage Site. The area she has been fighting to preserve includes the places where I have been doing my photography.

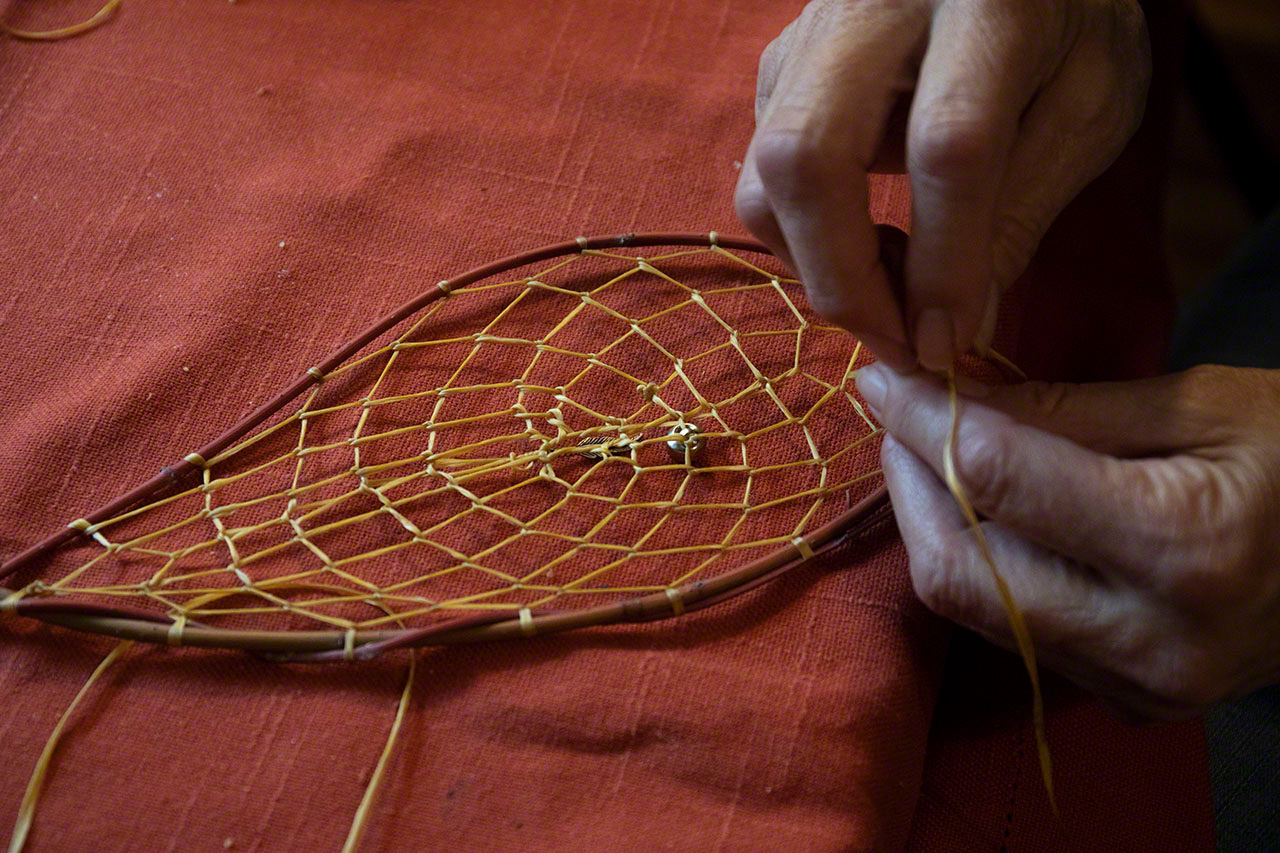

A traditional Anishinaabe dream catcher. (2019)

The Name of the White Wolf

I first met Sophia in the summer of 2010, at a Healing Camp. Anyone is welcome to join in this outdoor event, which is intended to help heal the spirit and aid people in exploring their roots. It included a sweat lodge, an important ceremony bringing purification and rebirth. A dome-shaped wooden frame is covered with cloth, and glowing-hot stones are placed in a hole in the ground, where hot water with medicinal herbs is poured over them. An Elder tells stories and sings accompanied by a drumbeat. Participants sit in a circle in the dark, wrapped in the steam and in their own sweat, and take turns telling their stories. When I told about my journey chasing my dream wolf I had begun years before, an Elder honored me with the spirit name Waabishkizi Ma’iingun, which means “white wolf.” Sophia explains that “In our stories, the wolf is one of our spiritual helpers, who carries a message between different communities or countries. In one sacred teaching, the wolf is a symbol of humility.”

Clockwise from upper left: A Healing Camp on Weaver Lake; singing with the drumbeat; taking an eagle feather in hand to speak during the morning gathering; smudging, or spiritual cleansing using burning sage. (2010)

The Life Giving Land

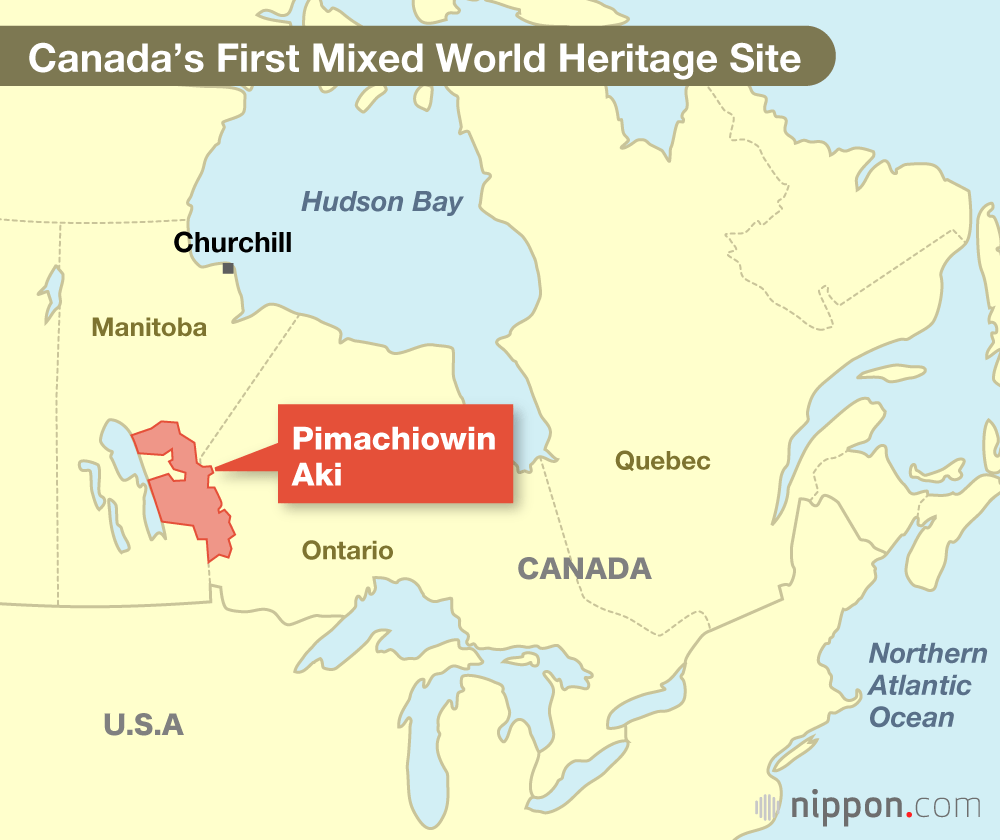

The name registered for the land in the UNESCO World Heritage application is Pimachiowin Aki , which means “the land that gives life.” Since there are no obvious objects to protect, such as large-scale ruins or endemic species, it was extremely difficult to explain the idea to UNESCO. However, in July 2018, after over a decade of hard work, the region became Canada’s first mixed cultural and natural World Heritage Site. With that, we could finally say that action to preserve this natural environment was at the starting line.

That autumn, I camped out with Anishinaabe families on a moose hunt, something I had long been hoping to do. I documented their catching fish, picking medicinal herbs, and after around a week, taking a moose. Dressing the moose carcass is not work for these hunters, it is a ceremony—an expression of gratitude for a blessing from the land.

An Anishinaabe family heading out on a moose hunt. (2018)

Reading the Environment

Churchill is a small town on the northern edge of the Northwoods, on Hudson Bay. It’s a famous place for photographing polar bears, and I first visited there in the autumn of 2013. I left for Churchill in mid-October, when polar bears begin to gather to wait for the bay to freeze. The bears’ main prey are seals. They hunt seals resting atop ice floes or when they come back for air at holes in the ice.

In February 2015, I waited near a polar bear den for a three-month-old cub to emerge into the open for the first time. I waited there for 12 days in the bitter cold, which dropped as low as –50 degrees with the wind chill. The cub finally appeared. Seeing it in the cold made it clear how well adapted these animals are to their harsh environment.

A polar bear mother and cubs huddling in the twilight. (2015)

Dr. Jim Duncan also helped me better understand the woods. Duncan is one of the world’s leading owl experts, and he has studied great gray owls for over 30 years. In the spring of 2015, he helped me document great gray owl rearing, from egg laying to leaving the nest, from a hide about five meters above the ground. I was also able to observe barred owls, long-eared owls, and great horned owls in the nest.

I learned many things in that time. No species of owl builds its own nests, Jim taught me. They use tree cavities or woodpecker holes, or take over abandoned crow, eagle, or hawk nests. Every type of owl also has their own preferred nest shape and prey, and their own habitat. Learning all this about owl lifestyles also showed me how to recognize the subtle variations in the forest, which I had once seen as a single thing.

A great gray owl bringing a meadow vole back to the nest. (2015)

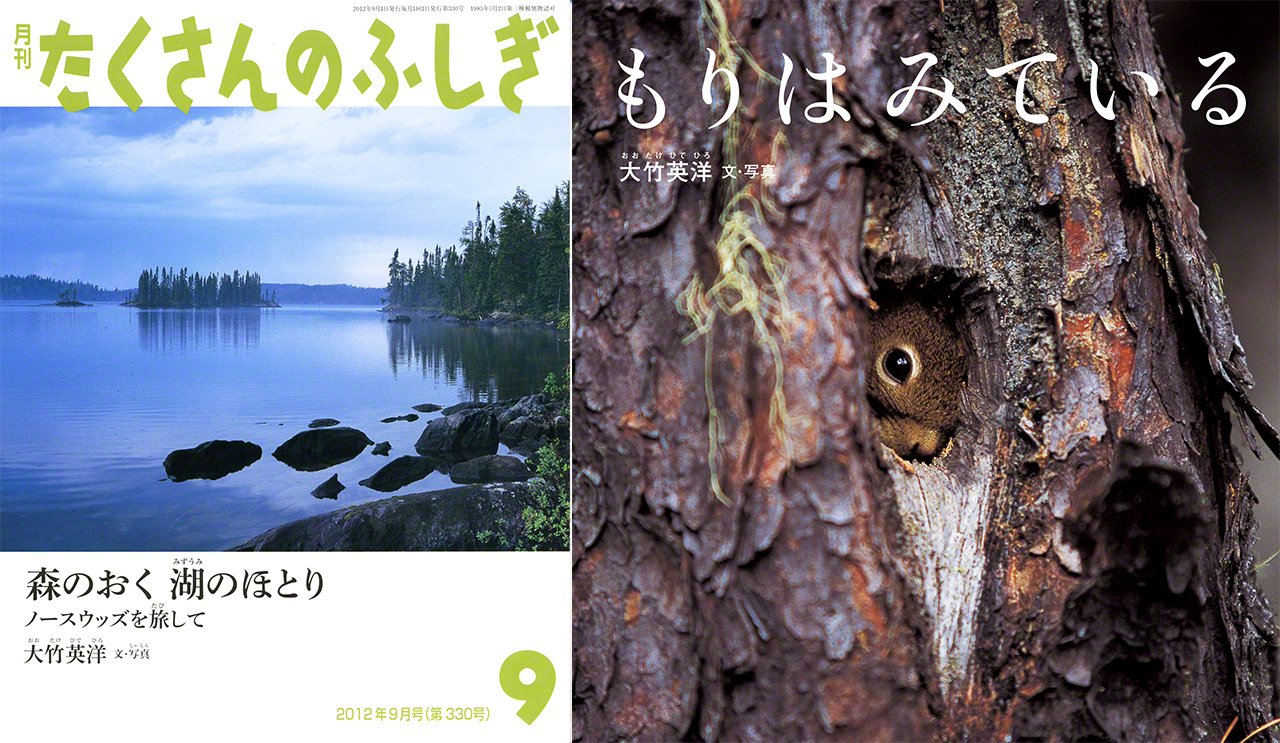

I continued to put out books of pictures for children every few years as I kept traveling to the Northwoods. Just why have I spent so many years visiting these woods? To help people understand that, I collected pictures that I find particularly important, with my own explanations, in Mori no oku mizuumi no hotori (Deep Among the Trees, Down Beside the Lake). I also put out the book Mori wa miteiru (The Watching Woods), a publication through which I wanted to show how I may have felt as if I was watching the woods, but actually I was the one being watched.

Mori no oku mizuumi no hotori (Deep Among the Trees, Down Beside the Lake), the September 2012 issue of Takusan no fushigi (A World of Wonders), and Mori wa miteiru (The Watching Woods).

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Delayed Dreams

I never stopped searching for wolves. I slowly expanded my network of people and information, and eventually it bore fruit. In March of 2018, I witnessed a pack of wolves eating a deer carcass outside of Ely. Finally, I was able to get a glimpse of how wolves lived in the wilderness. Ten days later, my book Soshite, boku wa tabi ni deta (And So I Set Out) won the seventh Umesao Tadao Literary Prize for Mountaineering and Exploration. That book covered my first trip to Ely, back in 1999, when I set out to chase the dream wolf. It seemed as if, finally, my long journey was showing signs of real progress.

Wolves eating a deer on a riverbank. (2018)

I had talked to a publisher about publishing a photobook collection when I succeeded in scheduling a major exhibition. I was able to do just that, with a two-week exhibition planned from the end of February 2020 at Fujifilm Square in Tokyo Midtown.

A Canadian lynx sits by a fireweed plant. (2010)

As discussed, we began planning my first major photobook. I couldn’t think of anyone better than the photographer I most admired, Jim Brandenburg, to write the foreword. When I went to Minnesota to ask him, he said yes immediately. Reading the foreword he sent me brought tears to my eyes. He wrote, “Shared and lived passions like this create a brotherhood bond—we chose the same path.” Twenty years before, my dream of becoming Jim’s assistant fell through, but I realized that in itself had been important.

An arctic hare in its winter fur. (2015)

However, life is full of unexpected turns. Just as my book was finally published, and my exhibition at Fujifilm Square was set to go, the pandemic struck. The opening day lecture was canceled, and then the exhibition itself ended halfway through. The State of Emergency declaration meant that many bookstores closed, and my dreams of a truly big release for my book were pushed back yet again by the coming of COVID-19.

The North Star above my head. (2018)

Still Guided by the Wolf

In February 2021, I set out for Hokkaidō, the northernmost of Japan’s four main islands, on a job. I thought it would be a good chance to also learn more about Hokkaidō’s Indigenous Ainu people, so I visited the Nibutani Kotan of Biratori, where many of their traditions are kept alive, and Upopoy National Ainu Museum in Shiraoi, a new facility established to promote understanding and awareness of the Ainu people. I visited the museum on a very windy day just after a blizzard settled. As I was walking around outside the museum, though, I received word that I had won the fortieth Domon Ken Award—one of the most prestigious awards for photography in Japan. I felt an exhilaration like the wind blowing through me; my effort had been rewarded at last. At the same time, the cold wind made me feel tense, as I realized all of the things that I had not yet been able to do.

I had been feeling my way through the dark woods for these past 20 years. I had hit dead ends, and had wandered off on detours. But I had been able to keep moving forward thanks to the many people who had helped me on the way.

I was not done, though. There are still so many places in the Northwoods I have not gone. I still want to document the Anishinaabe’s traditional lifestyles, which are rapidly changing. And above all, I still want to capture a portrait of the wolves that truly satisfied. Could I, a son of metropolitan Tokyo, get truly close to the wild wolf? That is exactly the story of the relationship between humanity and nature I want to tell.

On the day I set out to become a photographer, I wondered where that dream wolf was going to lead me. I will continue to pursue this quest so that I can see it with my own eyes.

Ice glittering in the morning light on the shores of Lake Superior. (2018)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Two polar bear cubs sparring alongside their mother, 2015. All photographs © Ōtake Hidehiro.)

nature animal environment Ainu photographer indigenous Domon Ken