The Gods of Japanese Myths and Legends

Myth and Legend: The Stories of Susanoo and Hachiman

Guide to Japan Culture Lifestyle History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Japanese pantheon is populated by a host of deities from mythology and folk belief who are enshrined at the some 80,000 Shintō shrines spread across the country. Among this myriad kami, Susanoo, the tempestuous brother of the sun goddess Amaterasu, and Hachiman, a god with a mysterious past, are highly revered and have a multitude of dedicated shrines. In the following I look at how the pair emerged as two of Japan’s most highly respected deities.

Villain to Hero

According to Japanese mythology, the creator deity Izanagi travels to the defiled land of Yomi to bring back his deceased bride, Izanami. Failing in his quest, he ritually purifies himself, producing a host of kami in the process. The most important of these offspring, created as Izanagi cleanses his face, are Amaterasu, the sun goddess and foremost deity in the Japanese pantheon, and Susanoo, an impetuous kami who comes into being from his father’s nose.

Susanoo, in contrast to Amaterasu, is a chaotic force, rampaging through the plain of high heaven and wreaking havoc among its divine inhabitants. He is expelled for his acts, descending to the ancient land of Izumo in what today is the eastern portion of Shimane Prefecture. A chaotic figure while in the heavens, once on earth, he goes through a dramatic transformation of character.

In Izumo, Susanoo meets an old man and woman weeping bitterly for their daughter Kushinadahime. The pair tell the deity of the impending arrival of Yamata no Orochi, a terrible serpent with eight heads, eights tails, and a body long enough to cover eight mountains and valleys. The beast devours one of the couple’s daughters each time it appears, and Kushinadahime, their eighth and last child, is soon to follow the tragic destiny of her sisters.

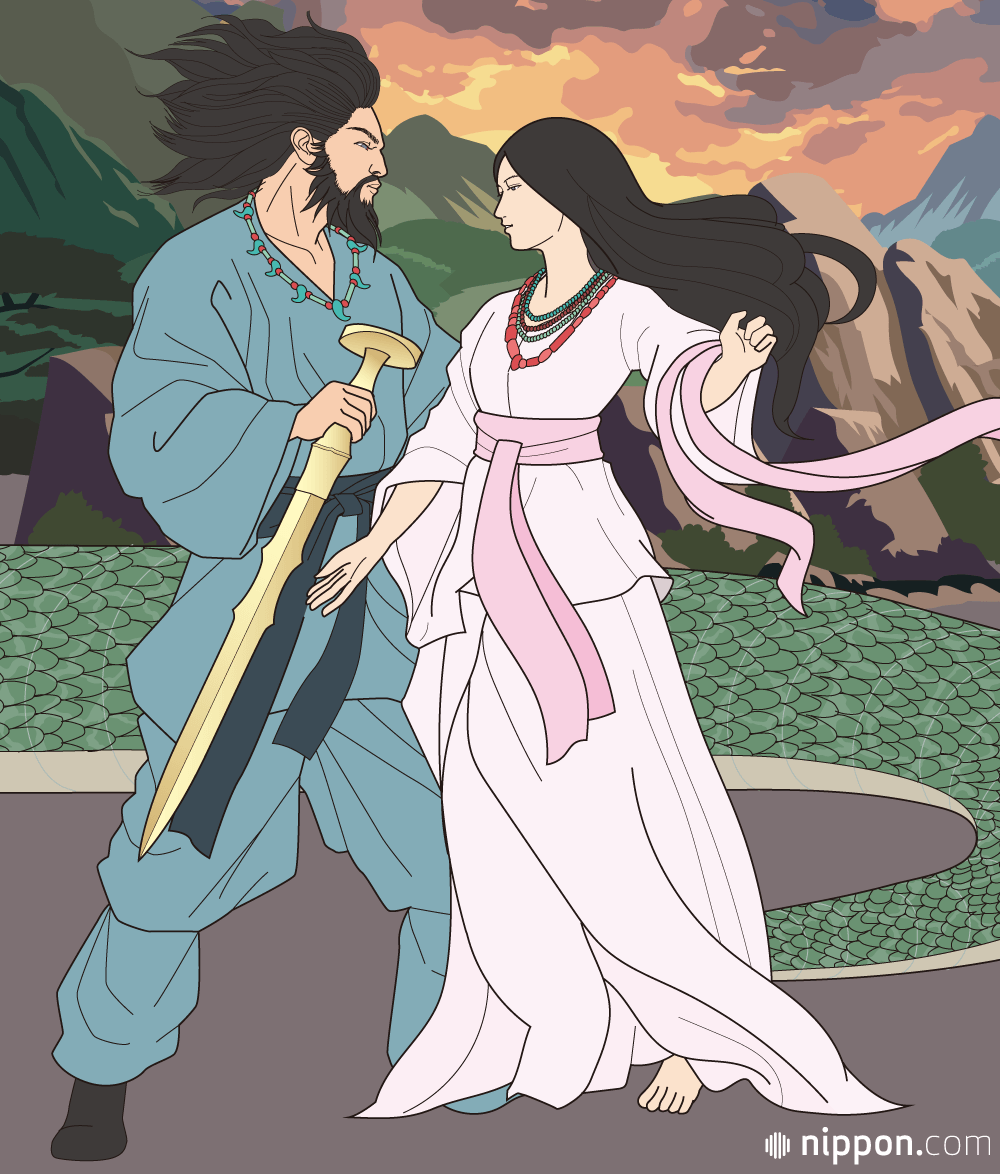

Moved by their predicament, Susanoo agrees to vanquish Yamata no Orochi on the condition that Kushinadahime become his bride. Turning his attention to ensnaring the beast, he has strong sake brewed and placed in eight earthenware vessels. Drawn by the sake, Yamata no Orochi drinks its fill and falls asleep, at which time Susanoo swoops in and lops off each of its heads. From the body of the dead creature emerges the Kusanagi no Tsurugi, a sword revered as one of the three sacred treasures of the Japanese imperial household.

Susanoo and Kushinadahime. (© Satō Tadashi)

The story of Susanoo and Yamata no Orochi is in the fashion of such tales as Perseus and Andromeda from Greek mythology that describe valiant warriors rescuing maidens. The legend sets the stage for Susanoo’s dramatic turnabout from a detested, temperamental kami to a revered hero.

A Kami for Lovers

As the setting of the story, the Izumo region boasts a number of shrines dedicated to Susanoo. Not all patrons visiting these sites come to pay homage to the kami’s heroic deeds, though. As the tale of Susanoo and Kushinadahime is as much a love story as a heroic account, the two lovers are regarded as providing assistance in matters of the heart.

After defeating Yamata no Orochi, Susanoo and Kushinadahime begin searching for a place to live. Finding Suga in Izumo much to their liking, the couple construct a palace, marry, and produce a host of divine children. Suga Shrine stands on the legendary site and houses three sacred rocks dedicated to Susanoo, Kushinadahime, and their child Yashimajinumi. Today, the shrines are famous for enmusubi—bonds that link people, most notably in love and matrimony—drawing worshippers looking for romance along with couples hoping to ensure a long and fruitful relationship.

Suga Shrine. The stone at center is inscribed with a waka, purportedly the first ever written, attributed to Susanoo and said to be the origin of the name Izumo. (© Pixta)

Yaegaki Shrine in Matsue in the eastern part of the Izumo region is, according to legend, where Susanoo constructed an eight-layer fence to protect Kushinadahime from the Yamata no Orochi. Like Suga Shrine, it is associated with enmusubi. Visitors anxious about their prospects for romance come to Kagami-ike, a pond connected with Kushinadahime, to divine their fortunes by placing a coin atop a square of paper floated on the water’s surface. The time it takes for the coin to sink and its proximity to the edge of the pond foretells how soon, or late, love will come and whether the prospective lover is someone near or far.

Kagami-ike, or Mirror Pond, at Yaegaki Shrine. (© Pixta)

The writer Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904), famous for his compilations of classic Japanese tales, visited the shrine after reading the Yamata no Orochi legend. Illustrating Susanoo’s standing as a god of enmusubi, Hearn noted the number of youthful patrons at the shrine praying for luck in love.

This reputation for enmusubi is shared by Susanoo’s descendent Ōkuninushi-no-kami, who is strongly associated with the myth of the Hare of Inaba that appears in the eighth-century chronicle Kojiki. In the legend he comes across the injured hare, who has been stripped of its fur by sharks while crossing the sea from the Oki Islands, and advises the animal to ease its pain by washing in fresh water and rolling in pollen of the bulrush. However, it is his reputation as a lover—he had six wives and sired 180 children—that installed him as a god of enmusubi at Izumo Taisha, one of the holiest shrines in Shintō.

Hikawa Shrine

The Kantō Region, centering on Saitama Prefecture and the Tokyo Metropolis, also has a strong tradition of worshipping Susanoo. The area is home to a vast array of Hikawa Shrines, some 280, dedicated to Susanoo. The name Hikawa is thought to originate from Shimane’s Hiikawa (Hii River), where Susanoo slayed Yamata no Orochi.

The haiden (hall of worship) at Hikawa Shrine. (© Pixta)

The highest ranking of this conglomerate of shrines is the Musashi Ichinomiya Hikawa Shrine in Ōmiya Ward in the capital of Saitama. The title ichinomiya, literally “first shrine,” comes from a Heian-period (794–1185) system for ranking shrines in each province. As the name indicates, the ancient shrine was an important place of Shintō worship in the former Musashi province, which included most of what today is Saitama and Tokyo and parts of Kanagawa Prefecture.

Along with Susanoo, Hikawa Shrine preserves the spirits of Kushinadahime and Ōkuninushi-no-kami, from which it has in recent years garnered a reputation for enmusubi. Another indication of the shrine’s origins in the Yamata-no-Orochi legend is the Ja-no-ike, a pond within the shrine precincts whose name suggests the mythological serpent. Formed by natural spring water bubbling up from deep underground, the pond is thought to be the birthplace of the shrine, with its water flowing into the sacred Kami-ike that extends over much of the shrine grounds.

Kami of Emperors and Samurai

Standing alongside Susanoo in terms of the breadth of worshippers is the god Hachiman. Shrines dedicated to the deity are the most abundant in Japan, outnumbering even the ubiquitous Inari shrines, recognizable by their vermillion torii and guardian foxes.

Although a widely revered kami, Hachiman’s origins are shrouded in mystery. The deity is not among the kami that appear in the Kojiki and Nihon shoki, Japan’s two oldest chronicles, nor does he appear in other ancient records. The most that is known is that worship of Hachiman first arose in the Usa district in modern day Ōita Prefecture on the island of Kyūshū, and that in time the deity came to be identified with the legendary emperor Ōjin. This latter development is significant as it raised Hachiman’s status, making him another ancestor deity of the imperial family, alongside the sun goddess Amaterasu.

The events that lifted Hachiman from an obscure kami worshipped in far-off Kyūshū to a deity revered by the imperial court date back to the construction of the Great Buddha at Tōdaiji in Nara. At the time, an oracle declared that Hachiman would watch over the construction of the Buddhist image. An oracle would again call on Hachiman to help quell unrest within the imperial family over succession to the throne and ensure a stable line of emperors. The establishment of the Iwashimizu Hachiman Shrine in Kyoto made him an important kami in the capital, and he was also bestowed by the imperial family the Buddhist title Daibosatsu, becoming a protector kami of Buddhism worshipped under shinbutsu shūgō, a belief system combining both Buddhism and Shintō.

The main hall of Kyoto’s Ishishimizu Hachiman Shrine. (© Pixta)

During the middle ages, the powerful Minamoto clan took Hachiman as their ujigami (clan deity), helping propagate the worship of the deity even further. In his youth, famed military commander Minamoto no Yoshiie (1039–1106) conducted his coming-of-age ceremony at Iwashimizu Hachiman Shrine and later came to be known by the title Hachimantarō, or “firstborn son of Hachiman.” When Yoshiie’s descendent Minamoto no Yoritomo founded a new government in Kamakura in 1185, he established a branch shrine, the Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine, in the new feudal capital.

Yoritomo inaugurated nearly 700 years of warrior rule in Japan, and subsequent military leaders sought the divine support of Hachiman, bolstering the popularity of the deity among the warrior class. Branch shrines were built throughout the country, and in time Hachiman became the mostly widely venerated kami in Japan.

Protector of Children

Adding to Hachiman’s popular appeal is the deity’s reputation for looking over the wellbeing of people, particularly small children. This status comes from the legendary tale of Emperor Ōjin and his mother, the Empress Jingū. The empress is commonly enshrined at Hachiman shrines alongside the spirit of her husband, Ōjin’s father Emperor Chūai, and various himegami (the wives and daughters of the main shrine deity).

According to the Kojiki and Nihon shoki, Chūai was preparing to lead his troops against a hostile foe in Kyūshū when Jingū became possessed by a kami who told the emperor to invade Korea. Chūai ignored the order and was killed by the vengeful spirit. Jingū, who was pregnant with Ōjin, took up her husband’s banner and led the army across the sea to Korea, where in the heat of battle she was overcome by labor pains. Tying a stone to her waist, she suppressed the pangs and continued the campaign, keeping her son in her womb until she returned to Japan.

Back in her homeland, Jingū had plans of putting Ōjin on the throne, but she faced fierce competition from supporters of the children of Chūai’s other consorts. Feigning Ōjin’s death, Jingū cleverly deceived her rivals into dropping their guard, enabling the empress to defeat them on the field of battle and install her son as emperor.

Stones are piled around a statue of Jingū holding the infant Ōjin at Umi Hachiman Shrine in Fukuoka, which is said to be where the empress gave birth. (© Pixta)

From the legend, Hachiman shrines became associated with anzan, safety in pregnancy and childbirth, and even today, expectant mothers visit to pray for protection. The most revered site is the Umi Hachiman Shrine in Fukuoka, where Jingū is purported to have given birth to Ōjin upon returning to Japan.

The status of Hachiman as both a god of war and a guardian of children illustrates the multifaceted character of many Shintō kami, including the hero-cum-villain Susanoo, whose attributes draw worshippers of all stripes to shrines.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image © Satō Tadashi.)

Buddhism kami Kojiki myth Amaterasu shrines and temples Shinto Izumo Taisha