Ozu Yasujirō: A Director’s Time in Tateshina

Ozu Yasujirō and Noda Kōgo: Filmmaking Accomplices

Culture Entertainment People Cinema- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Teaming Up on Masterpieces

Ozu Yasujirō (1903–63) is celebrated as one of Japan’s, and the world’s, finest film directors. But few people recognize the fundamental role played by the scriptwriter Noda Kōgo (1893–1968) in Ozu’s career. A visit to the mountains of central Japan 120 years after Ozu’s birth, and 60 after his passing, sheds fresh light on the legacy of the writer who always worked with the famed director, producing a personal and documentary archive that tells a part of Japan’s movie history built on the close friendship between the two.

During their time together, Ozu and Noda crafted a unique filmmaking workflow that has had a lasting impact right up through our age. In the last stage of their careers, during the early postwar decades, both artists secluded themselves in Tateshina, a remote, mountainous part of Nagano Prefecture. There, they took inspiration and shaped a shared routine full of hours of work, conversations, walks, and lots of sake. This would be a place for creation, but also for a celebration of life, until the end of their days.

Noda Kōgo was born in 1893, and was thus a decade the elder of the creator of the “tatami shot.” He shared Ozu’s beginnings in silent film, and together they made their way into the color era. He was not just a prolific creator and contributor to the art in Japan, but also a good friend to Ozu.

Moving images joined them in Tokyo in the 1920s, when Ozu debuted as a director with the 1927 Zange no yaiba (Sword of Penitence), on a script by Noda. From that point onward, they would go on to make 27 films together, although there was an interruption of more than a decade between the 1935 Hakoiri musume (An Innocent Maid) and the 1949 Banshun (Late Spring).

The 1930s rise of Japanese militarism and the outbreak of World War II forked their paths, as state control and propaganda clenched their fist around the cinema industry. While Ozu was sent to China in 1937 and Singapore in 1943, to shoot documentary footage in the middle of the conflict, Noda travelled to central China in 1940 to write the script for a war movie based on the biography of writer Kikuchi Kan.

A Reunion Leads to Masterpieces

Ozu and Noda’s reunion in the postwar years kickstarted a series of films that would be called “Noriko’s trilogy,” named for the lead character given life by Hara Setsuko. These films would take them all to stardom: the 1949 Late Spring, the 1951 Bakushū (Early Summer), and the 1953 Tōkyō monogatari (Tokyo Story). The final film in the series in particular represented an artistic apex for both authors.

When shooting was over, they mainly spent time in or near Tokyo, particularly in Kanagawa Prefecture’s Kamakura. Both filmmakers worked at an inn at the nearby Chigasaki Beach, within commuting distance of the Shōchiku movie studios in Ōfuna. Here they came up with story plots, wrote dialogue, and organized the casts for each of their films. Nevertheless, they ended up exhausted, due to the fast-paced rhythm of the film industry and the inn itself, which housed many moviemakers and writers of that time, while exposing them to the public eye.

They thus decided to escape in search of inspiration. Noda knew the perfect place: an isolated mountain villa surrounded by forests, where only the clouds will come to visit. Thus, they reach Tateshina Heights, a volcanic spot in Nagano Prefecture’s impressive Yatsugatake mountain range, which would become the last retreat of both filmmakers.

Noda Kōgo (left) and Ozu Yasujirō (at center) enjoy the natural environs in Tateshina. (Courtesy of the Noda Kōgo Memorial Tateshina Writers Research Institute)

Heading North

Yamanouchi Michiko, executor to the mountain villa that now stores Noda’s personal archive, notes that the scriptwriter visited Tateshina in the summer of 1951. There Noda’s brother had acquired a tiny villa with a single tatami room that was the living room during the day and the bedroom at night. This property came to Noda, who surrendered himself to all that quiet and beauty, never parting from it again.

Yamanouchi Michiko is executor to the Shin-Unkosō, where Noda Kōgo’s personal archive is stored. (© Kodera Kei)

The rustic Shin-Unkosō. (© Kodera Kei)

“Mountains call up to the clouds, as clouds call down to people,” said Noda, giving the name to the Unkosō, the “villa calling to the clouds.” The place would see relatives, friends, and artists of the time, among them actors like Sada Keiji and Ryū Chishū. During the summer, visitors would walk in the woods or gather at night around the fire. Noda’s residence was in Kamakura, but he spent long spells in Tateshina with his wife, Shizu, and Reiko, their daughter. It was here where he decided to leave his legacy.

Reiko grew up surrounded by filmmakers, and became her father’s right hand and typing clean copies of the scripts Noda wrote. Both Ozu and Noda would ask for her input while creating, making it no surprise that she became a scriptwriter herself, under the pseudonym of Tachihara Ryū. In spite of strong initial opposition from her father, Reiko would end up marrying another scriptwriter, Yamanouchi Hisashi—a family episode that inspired the script for Higanbana (Equinox Flower, 1958), Ozu’s first color film.

From the left: Ozu Yasujirō, Noda Kōgo, his wife Shizu, and their daughter Reiko. (Courtesy of the Noda Kōgo Memorial Tateshina Writers Research Institute)

The Tateshina Diaries

With Noda as his guide, Ozu arrived at Tateshina for the first time in August 1954. In this season, at 1,200 meters above sea level, the trees are at their greenest, days are bearable, and nights are cool. That same day the filmmakers begin writing the Tateshina Diaries, a chronicle of their retreat.

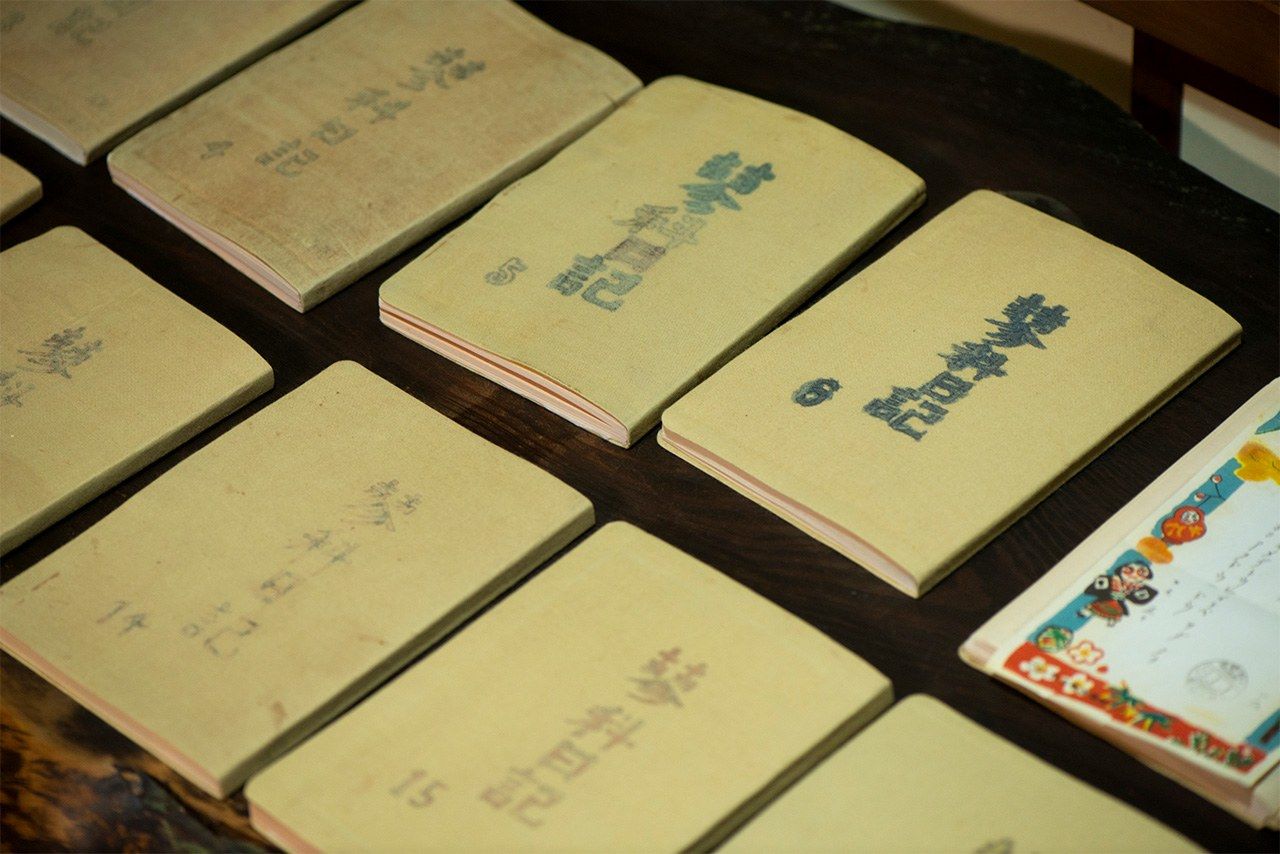

In a beige notebook of fine washi sheets they wrote down about their shared routine, day by day. They sketched and joked, and visitors also took part in the chronicle. In all they penned 18 notebooks full of anecdotes.

Their routine began by waking up after nine, taking a bath, and having lunch with plenty of sake. They then sat down to work, and in the afternoon, if the weather was good, they went out for a walk in the woods. On special occasions they even went to the local hot springs at sunset.

The filmmakers mixed Shizu’s home cooking and sake with cycles of creation and merrymaking in nature. As Shizu and others have said, there was one creative process for a movie that ended up requiring 100 bottles of sake; these piled up at the villa entrance during the three or four months that took them to build the plot, write the script, and organize the shooting.

They would then leave Tateshina Heights and start working on the cast. They never shot in this place, but a barber shop they frequented in nearby Chino inspired a scene in Ukikusa (Floating Weeds, 1959).

Ozu and Noda used to accompany their creative moments with Daiya Kiku sake. (© Kodera Kei)

A Villa from the Movie World

Ozu fell in love with the place and the quality of the sake from this rice-growing region. Following in his friend’s footsteps, he decided in 1956 to rent another villa and build his headquarters there, a short walk from the forest. He called it Mugeisō, a name combining both art (gei) and nothingness (mu). This would be where Ozu and Noda would come up with seven more films through their final outing, Sanma no aji (An Autumn Afternoon, 1962), Ozu’s last work.

The villa stands to this day, its gates open to visitors who listen to Fujimori Mitsuyoshi, the guide, as he takes them through Ozu’s and Noda’s evenings with other cinema celebrities, filled with beef and vegetable sukiyaki cooked by Ozu himself for his guests.

Mugeisō housed a lover, too. The Tateshina Diaries mention a 1956 visit by Murakami Shigeko, an accordion player who performed a piece for one of the scenes in Tokyo Story. “Everyone knew she was Ozu’s girlfriend,” says Fujimori. Other testimonies also confirm they had a close relationship. When she stayed in the villa, and according to the diaries, her accordion provided entertainment during the evening soirees.

Fujimori Mitsuyoshi tells stories of Ozu in his retreat, Mugeisō. (© Kodera Kei)

The exterior of Mugeisō. (© Kodera Kei)

A Copy of the Diaries to Recover the Past

Noda and Ozu said their definitive goodbyes on a cold December 12, 1963, at the Tokyo hospital where the director passed away at the age of 60. The saddened Noda wrote in his personal diary, in a note deciphered only recently by the Dōshisha University researcher Miyamoto Akiko, about Ozu’s last moments:

“Ozu-kun lowered his eyes and focused on my face, as if somehow he understood what the moment meant.”

Ozu’s passing did not stop Noda from writing the Tateshina Diaries the pair had composed during their artistic retreats. Five years later, though, in the late hours of September 23, 1968, death finally reached him in his mountain villa, and it was Shizu who opened the last notebook and recorded the fact, thus closing this registry of friendship and creation. Afterwards she stored the 18 tomes in a corner of the forest house.

In 1990 a developer acquired the land where the villa stood, and Reiko built a new villa for Shizu, close enough to maintain the original’s spirit and legacy. There she stored Noda’s and Ozu’s archives. Until her death in 2001 at age 100, Shizu kept the diary notebooks intact, as well as the original scripts from films like Early Summer and Tokyo Story, among many other curiosities from the old friendship.

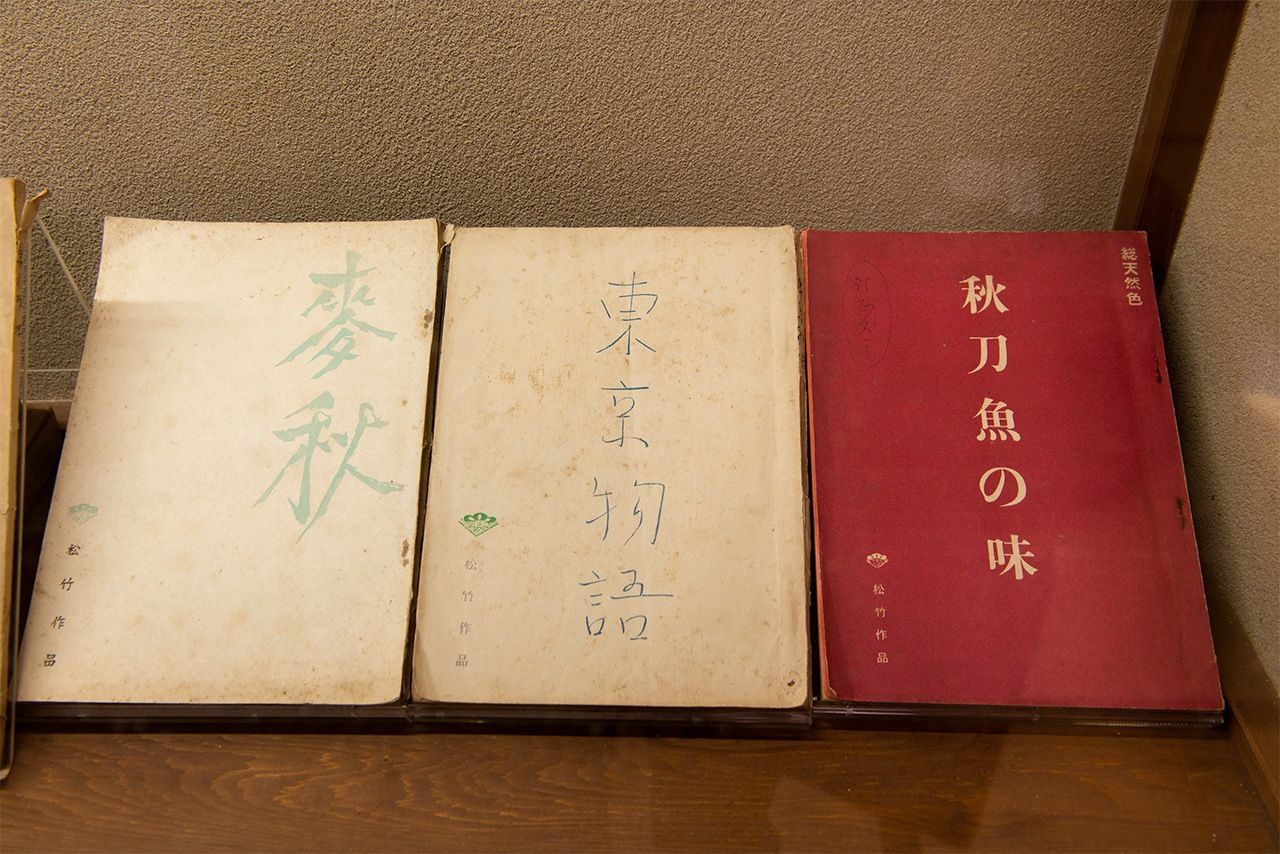

From left to right, the original scripts from Early Summer, Tokyo Story, and An Autumn Afternoon, as exhibited in the Shin-Unkosō villa. (© Kodera Kei)

Among the archives are some 8-millimeter films showing black and white images of their years in Tateshina. Ozu filmed Noda, and Noda, Ozu. These films include recordings of scenes of local life including nearby residents the locals, along with the natural bueauty of the area. Ozu plays golf wearing yukata and geta sandals in the woods, showing how these creators sought to break up their days of quiet filmmaking preparation.

At the beginning of this century, Noda’s daughter Reiko and her husband, Yamanouchi Hisashi, launched their own villa in these woods, with an eye on the legacy of her father and his celebrated friend. In 2013 their curation resulted in a publication of a limited edition of the diaries. After Reiko’s passing in 2012, her heirs thought it too valuable a legacy to keep it private, leading to the 2016 opening of the Shin-Unkosō and the launch of the Noda Kōgo Memorial Tateshina Writers Research Institute, which has made all the documentary assets available to film lovers and researchers, scanning and reprinting the fragile originals as color reproductions of the same exact size.

Reproductions of the Tateshina Diaries. (© Kodera Kei)

September 19, 2020, was a celebration day in Noda’s villa. In spite of the pandemic-related restrictions, Yamanouchi Michiko decorated the path to the house with flower arrangements to welcome the president and technicians of Fuji Xerox, which had worked to scan and reproduce the diaries; Chino’s mayor; the researcher Miyamoto; and a few friends and film celebrities. Yamanouchi Chiaki, also a scriptwriter, could not keep the emotion at bay. The small group commemorated the recovery of the diaries: a set of color reproductions lined on in the porch, under the forest clouds.

“Were Noda and Ozu to be here,” says Yamanouchi Michiko, Noda’s granddaughter, “they’d mock us for turning all this into a place for film history research.” Tireless workers of a golden age of cinema, but also fond of jokes and frugal in their celebration of life, Ozu Yasujirō and Noda Kōgo made their way through Tateshina decades ago, but their friendship remains evident in these white birch woods.

Ozu Yasujirō, at left, and Noda Kōgo in kimono. (Courtesy of the Noda Kōgo Memorial Tateshina Writers Research Institute)

(Translated into English from the Spanish original. Banner photo: Ozu Yasujirō, on the right, walks along a Tateshina Heights path with Noda Kōgo and Shizu, at far left. Courtesy of the Noda Kōgo Memorial Tateshina Writers Research Institute.)