Confronting the Years: A Photographer’s Tour of Japan’s Hyper-Aging Society

Inori Orchestra: Modern Memorials Crafted with Woodworking Mastery

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

What to Do with the Remains

As I get on in years, I sometimes hear a sound that had hitherto gone unnoticed—the footsteps of death. At such moments, my thoughts turn to how I will probably be cremated and how I want my remains to be laid to rest. Or if my beloved is the first to go, I wonder what I should do with her remains.

I was born in a traditional, thatched-roof house in the mountains of Nara. I have vague memories of how we used to pray to ancestors and deities at the butsudan and kamidana (household Buddhist and Shinto altars), placing fresh water, seasonal flowers, and food before them as offerings, burning incense, and chanting sutras. My eldest brother now looks after our family grave and the home altars, and I must admit that my emotional ties to my deceased parents, relatives, and ancestors have grown weaker over the years. This, I suspect, is not unrelated to the fact that I have little direct contact with a butsudan in my daily life.

The Butsudan as a Pure Land Paradise in Miniature

A gilded, Meiji-era butsudan showcasing the best of Buddhist artisanship. (Courtesy of the Hasegawa Ginza gallery)

A family altar is a miniature representation of the Buddhist Pure Land paradise, and its design has evolved with the times, coming to resemble living room furniture and then, in more recent years, taking on a more modern look. Despite this modernization, though, the share of households owning a butsudan has been declining as families have become increasingly nuclear and disconnected from multiple previous generations under one roof.

At the same time, this has been accompanied by a rise in the number of people keeping the remains—or a portion of the bones and ashes—of their loved ones at home. Some are adopting more personal approaches to memorializing the deceased, feeling less compunction to seek out a grave or butsudan.

A common issue for such people, though, is finding an appropriate casing to hold the remains.

Modern, Stylish Altars and Fittings

While searching for Buddhist furnishings aligned with my personal lifestyle, I happened upon a website offering an impressive lineup of modern and stylish butsudan and fittings. This was exactly what I was looking for! I grew so excited that I immediately contacted the maker of these items, Inblooms, and made an appointment to visit its office in the city of Shizuoka.

The company’s Inori products—a brand name literally taking the Japanese word for “prayer”—are very simple, unadorned, and unassuming, and yet have an undeniable presence. Unlike the religious solemnity of the traditional butsudan, the altars created by Inblooms are marked by airiness. Some are simply wooden frames—an unfettered design enabling wind to pass through and the sound of the altar bell to reverberate.

The A4 Butsudan is a wooden frame designed to hold an urn and an ihai tablet. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Inblooms has dramatically transformed the traditional altar for the modern lifestyle. One of its most popular products, as showcased on its online gallery Inori Orchestra, is the A4 Butsudan, whose height and width are literally the size of a standard A4 sheet of paper.

The wood surface is caressingly smooth. Holding the frame, I felt the natural wood quickly assimilating the warmth of my hands. I was fascinated by the limitless potential of the products before me. They stirred my senses, and I found myself taking one photo after another as a photographer.

The chairs in the Inblooms showroom were created by Danish furniture designer Hans J. Wegner. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

The Tenshi no Ouchi (home of angels) series serves as a casing for tiny urns. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

A Forest of Mortuary Tablets

An ihai is a mortuary tablet inscribed with a person’s posthumous Buddhist name and the date of death. The ihai is where the soul of the deceased is said to reside, and its color had, in the past, been invariably black. Inblooms, though, has created what it calls Mori no Ihai (forest ihai), a treasure trove of tablets that, when first launched, were available in over 200 types of natural wood. For my fruit-loving mother, for example, I could choose one made from an apple tree—a one-of-a-kind ihai allowing me to emotionally connect with my mom whenever I prayed.

The tablets in the Mori no Ihai series are now made from well over 100 types of trees. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

The groundbreaking series of ihai tablets was conferred a Good Design Award by the Japan Institute of Design Promotion in 2018. Jury members commented that it expanded people’s ihai options by enabling the personality of the deceased to be expressed through the chosen type of wood. Modern, innovatively designed Inori Orchestra products have been cited for the same award on a total of seven occasions.

The hint for many Inori products, says Inblooms President Kikuchi Naoto, came from Scandinavian furniture design. “The chairs in our showroom were built by artisans with great care using excellent materials,” he comments. “If they break, they’re repaired, not replaced. That’s how things were done in Japan in the past. The products in our Inori Orchestra lineup aim for the same level of quality. The simpler the design, the easier it is to discern what’s essential.”

Carrying On the Woodworker’s Craft

Kikuchi’s love for wood stems from what his uncle, who worked as a carpenter at Shizuoka Sengen Shrine, taught him. In the early 1800s, some of the best carpenters from around the country were assembled by the Tokugawa shogunate to construct the buildings now standing at that shrine. The descendants of those miyadaiku, carpenters specializing in temple and shrine construction and repair, who stayed on began using joinery techniques to assemble what has come to be called Suruga sashimono: furniture, butsudan, and other wood items made without the use of nails.

Today, even these local specialties are increasingly outsourced to lower-priced, overseas suppliers. “One of my aims in launching Inori Orchestra,” Kikuchi says, “was to give local woodworkers opportunities to hone their skills.”

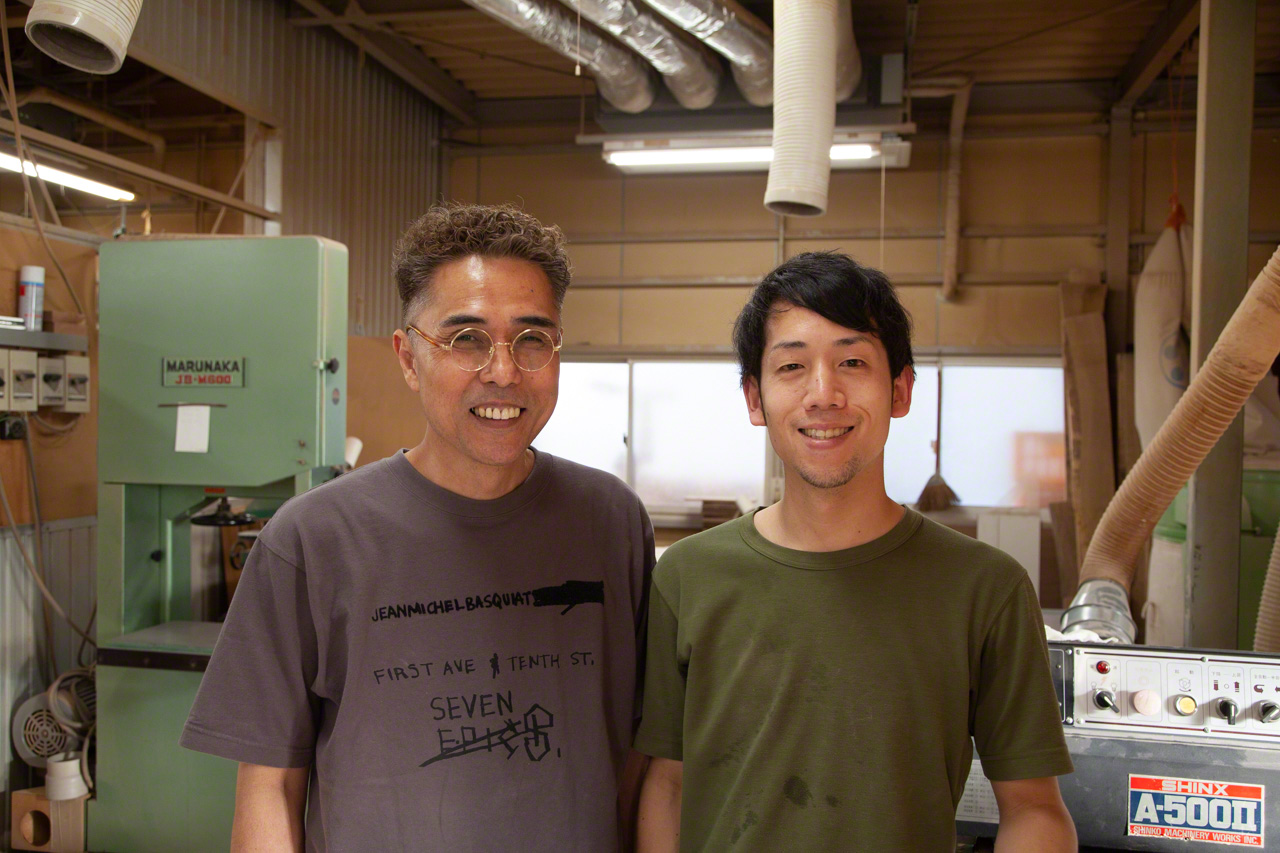

One such artisan is veteran woodworker Yasuda Masahiro, whom I visited at his workshop. “The orders I receive for Inori products are quite demanding,” he admits. “And sometimes, the requirements seem unreasonably difficult. But at the same time, I’m eager to rise to the challenge. Clearing the technical hurdles can broaden my skill set and open new doors. Kikuchi tells me what customers are saying, so that keeps me on my toes.”

Inblooms’s Kikuchi believes in delegating the assembly of his beloved products to those who truly share his enthusiasm—a description that fits Yasuda well.

Yasuda makes a point of “reading” and “listening” to each piece of wood he uses. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Inori products are painstakingly polished by multiple artisans. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Yasuda hopes Japan’s woodworking tradition will be kept alive by younger generations of artisans. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

The Birth of the Inori Orchestra

Kikuchi went to work for a construction company after graduating from a land-surveying school in Nagoya and was placed in charge of designing and constructing garden cemeteries. This experience got him thinking about modern approaches to laying the deceased to rest and memorializing them. He then returned to Shizuoka, where he became a salesman for Volkswagen and emerged as his favorite car manufacturer’s top-selling dealer in Japan in his fourth year.

At around the same time, a Swiss company making “memorial diamonds” from the ashes of departed loved ones set up an office in Shizuoka. Kikuchi was struck by this novel idea and thought that it could offer a solution to the shortage of cemetery sites in Japan. He set up his own company to create Ash in Jewelry pendants and other accessories housing the remains of the deceased. The products were a hit.

A bracelet with a capsule for holding a loved one’s ashes. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Now, 18 years later, Kikuchi works with a small but trusted team of colleagues and continues to be personally engaged in everything from product development to photography, design, and packing. “We get many thank-you letters from our customers,” he notes. “They’re the ones who’ve been instrumental in getting us to where we are today. When I look around, I see many other makers offering products that look like Inori Orchestra. This means that the new genre of memorial items we’ve developed is finally gaining market acceptance.

“My wish is to become the Apple of the butsudan industry—a constant source of innovation. Perhaps someday, maybe after I die, our product forms will become as universal as a clothes hanger, prompting people to say, ‘Gee, I wonder who designed that?’”

The Yurikago miniature urn for the ashes of infants, evocative of a young child lying in a yurikago, or cradle. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

The Art Glass urn is produced by glassblowers. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

An Ossuary of Light and Resonating Souls

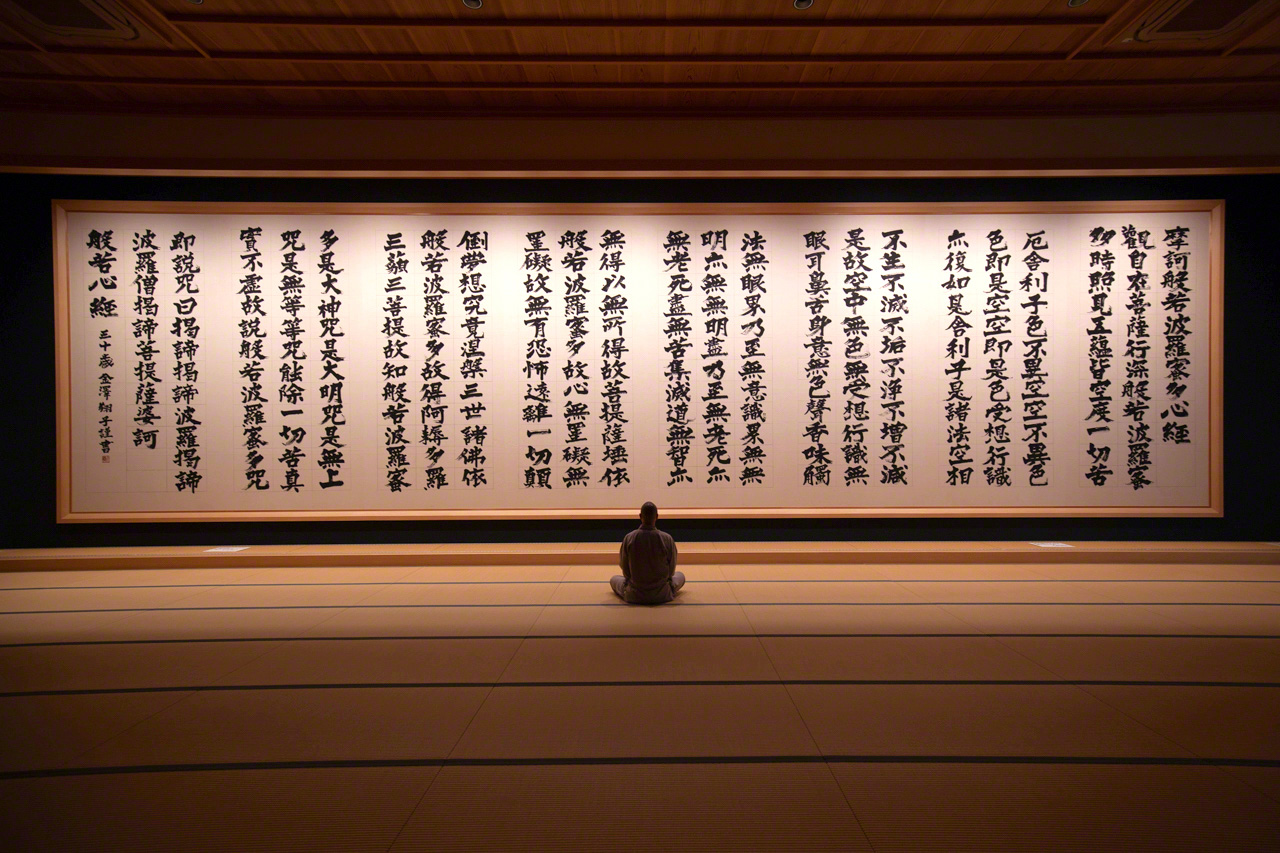

Fascinated by the skills of glassmakers, Kikuchi launched a line of urns made by glassblowing. An avid fan of these beautiful urns is Kimiya Kōshi, head priest of Ryōunji, a Buddhist temple in the city of Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, home to the world’s largest version of the Heart Sutra, written by calligrapher Kanazawa Shōko. I decided to make a visit to the temple.

Ryōunji head priest Kimiya Kōshi sits before the Heart Sutra, drawn by Kanazawa Shōko, a calligrapher with Down syndrome. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

At the other end of the hall is an ossuary with 266 illuminated glass urns—the same number as the characters in the Heart Sutra. I was struck by the sight of a visitor who arrived after dusk and stood before an urn for a very long time.

Urns permeated by light resemble stars in the evening sky. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

A woman stood praying before the ossuary for a long time as dusk turned to night. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Tenshi Jizō statues were made to pray for an early end to the COVID-19 pandemic. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

In praying and making offerings to the dead, we are extending our thoughts to them, feeling their presence, and resonating at the same vibrational frequency. Like the sun and moon, light shines forth from one and is reflected by the other. And like our two hands, one meets the other in silent prayer.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Inori Ouchi is a natural wood butsudan that is perfectly at home in modern surroundings. © Ōnishi Naruaki.)