New Documentary Film about Calligrapher Kanazawa Shōko and Living with Down Syndrome

Cinema Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

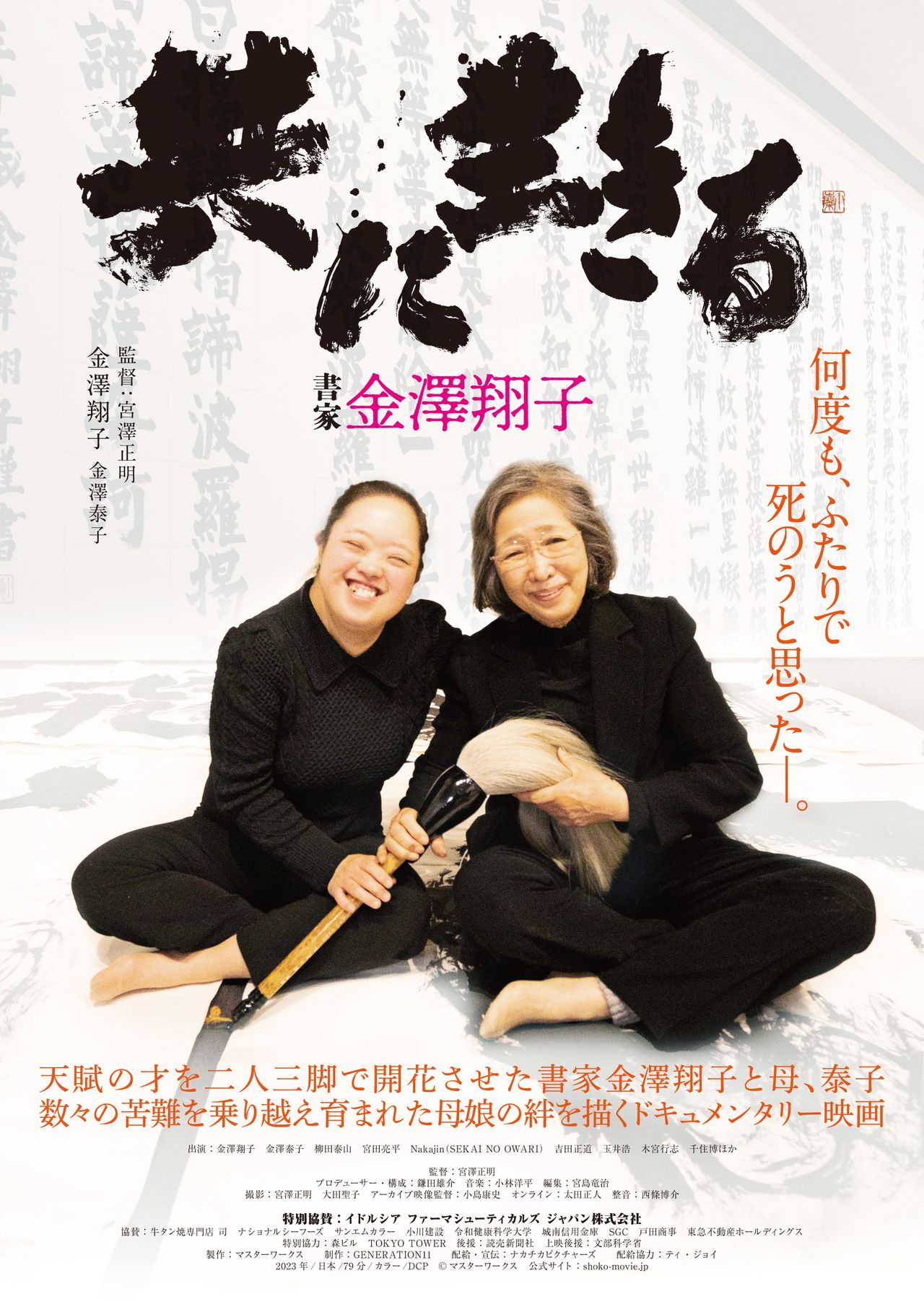

Tomo ni ikiru: Shoka Kanazawa Shōko (Living Together: Kanazawa Shōko, Calligrapher) is the second film Miyazawa Masaaki has made as a director. It was made remarkably quickly, going from initial concept to completion in just a year and a half. Eschewing lengthy explanations and voiceovers, the film focuses instead on images full of life and movement, accompanied by a moving soundtrack. Mixing intimate footage of their daily lives while looking back on the past and incorporating testimonies from people who know them, Tomo ni ikiru depicts the unbreakable bond between mother and daughter and paints a revealing picture of a gifted artist. The director’s hope is to bring the strength and energy of Kanazawa’s calligraphy to the big screen and in high definition and to reach out to audiences around the world, regardless of language and cultural background.

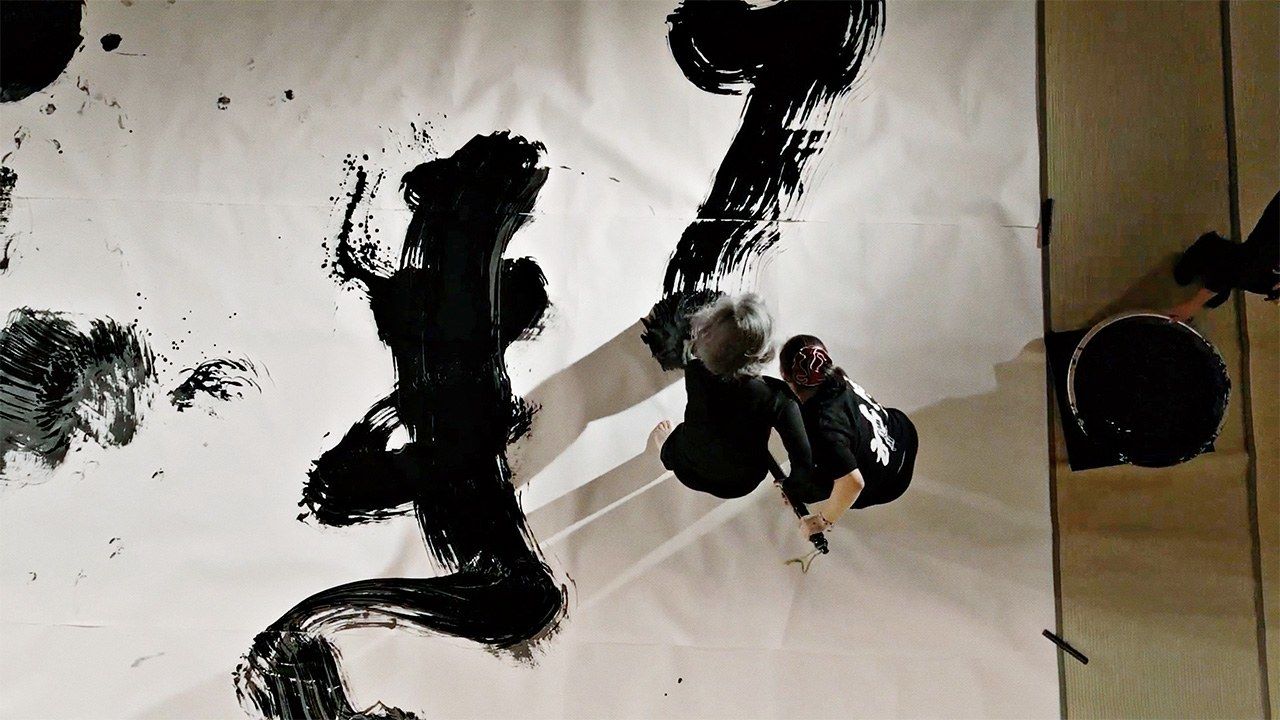

Miyazawa first encountered Shōko’s calligraphy in December 2021, when a solo exhibition of her work, Tsuki no hikari (Light of the Moon), was held at the Mori Arts Center Gallery in Roppongi Hills. Miyazawa was astonished by the energy and movement of the brushstrokes, and by the vivid contrast between the white of the washi paper and the jet black of the calligrapher’s ink. This was more than just calligraphy, he felt: This was art.

Where did this expressive power come from? Miyazawa decided the best way to answer this question was to get as close as possible to Shōko and her mother Yasuko in their daily lives. By sharing this time with them, he has produced a documentary film that gives audiences a precious glimpse of their bond and the story behind Shōko’s remarkable art.

Kanazawa Shōko and her mother Yasuko with director Miyazawa Masaaki at an event to mark the completion of the film Tomo ni ikiru: Shoka Kanazawa Shōko. © nippon.com

An Intimate Portrait of the Mother-Daughter Bond

In April 2022, Miyazawa’s camera was on hand to record an important moment as mother and daughter moved away from the house where Shōko was born, so full of memories and associations. Their new base of operations, not far from where they used to live in a quiet, everyday shopping street in Kugahara in Ōta, Tokyo, features a new gallery and studio as well as living quarters.

Eight years earlier, Shōko moved out to start living on her own, within a few minutes’ walk of where her mother lived. With this latest move, their lives were about to enter a new phase. On the ground floor of the new apartment is a gallery that will exhibit Shōko’s work. On the second is a classroom where Yasuko will give calligraphy lessons. The upper floors are where mother and daughter will live together again—although this time, on separate floors.

Shōko looks out from the balcony of her new home. (© Masterworks)

“For any mother who has a child with a disability,” Yasuko says, “one question matters more than anything else: Will my child be able to survive after I’m gone?”

Shōko has always been sensitive to the feelings of people around her. She picked up on her mother’s wish to see her established on her own two feet, and one day announced an ambition to move out and live on her own when she was 30.

At first her mother had misgivings and even suspected that Shōko’s new life of independence might not last long. She was happy to be proven wrong. Shōko quickly learned to cope, with the people in the neighborhood keeping a watchful and affectionate eye on her as she grew used to life on her own. Rather than patronizing big supermarkets, Shōko preferred to visit small outlets in the traditional shopping street where she lived, clutching her money in her hand as she went from shop to shop. The shopkeepers and other residents of the neighborhood extended an affectionate welcome, and soon took Shōko under their wing. Yasuko felt reassured that here was a place Shōko could live in safety and security, even when her mother was no longer around to help.

Sutras Stained with Tears

The film looks back to the early days of Shōko’s first encounters with calligraphy, through old photographs and Yasuko’s memories. When Shōko was born in 1985, the situation for people with disabilities was more difficult than it is today. When Shōko was five, her mother started giving calligraphy classes to local children as a way of helping Shōko make friends before she started attending school.

Kanazawa Yasuko stands in front of Shōko’s “tear-stained Heart Sutra” calligraphy, at left. (© Masterworks)

Shōko started off at a regular school, and was blessed with understanding teachers. Yasuko felt valued when Shōko’s teacher told her, “Having Shōko here makes for a gentle and relaxed atmosphere in the whole classroom.” But this didn’t last long. When she was 10, Shōko was asked to move to a special needs school. Wrenched away from her familiar environment, she felt rejected, as if she had been told she was worthless and unwanted.

Her mother tried desperately to find an outlet for those negative emotions. The idea she came up with was to have Shōko copy out the Heart Sutra (Hannya Shingyō), a distillation of the wisdom sutras that is commonly recited by Japanese Buddhists and consists of just 272 characters in its Chinese translation.

“Thinking back on it now, it was a bit of a reckless thing to do,” recalls Yasuko. “She was only in fourth grade, ten years old. To ask a child with a disability who didn’t even know kanji to copy out a thing like that . . .”

Partly to assuage her mother’s distress, Shōko took to copying out characters almost all day every day, crying all the time. Her tears fell onto the paper as she wrote, but this didn’t stop her from writing out the sutra. The practice gave her remarkable powers of concentration and helped her master the kaisho (regular script) of calligraphy. Her talent for calligraphy was soon recognized by her mother’s teacher, Yanagida Taizan, fourth-generation head of the Yanagida school of calligraphy, which dates to the Edo Period (1603–1868) and specializes in this script. The pieces she produced at this time later became famous as her “tear-stained Heart Sutra” series.

A “One-Off” Solo Exhibition

When Shōko was 14, her father Hiroshi died suddenly. Several years later, Shōko and her mother were feeling depressed and defeated. Shōko had been looking for work, but without success. One day, Yasuko remembered something her late husband had once said: “When Shōko turns 20, let’s put on a show of her work. Just for once in her life, let people see what she can do as a calligrapher.”

And so, in December 2005, Yasuko helped to organize a solo exhibition of her daughter’s calligraphy in the Ginza district, center of the capital’s commercial art galleries. She felt certain this would be a one-off: the first and last time Shōko’s work would be put before the public. Against all her expectations, the show “Shōko: The World of Calligraphy” drew impressive crowds, and Shōko soon found herself in the national limelight, fêted as the “genius calligrapher with Down syndrome.”

Achieving a State of “No Mind”

The film is full of moving scenes of Shōko with brush in hand. Before writing calligraphy in her public appearances, she sits in formal seiza style and offers a prayer to the spirit of her deceased father. There is a hushed silence and something intangible seems to descend on the calligrapher. An instant later, she takes up the heavy brush and sweeps it apparently effortlessly across the paper. “I just want to make people happy,” she says. Even in front of large audiences, she says, she’s never felt nervous.

Yoshida Masamichi, head priest at Kenchōji temple in Kamakura, describes Shōko and her work as the epitome of what adherents of Zen aim for in their meditation practices. “Most of us, when we do calligraphy, are conscious of pressure to write the characters as well as we can. Shōko doesn’t seem to feel any of that. Her calligraphy captures perfectly the state of mushin or ‘no mind,’ when a person is totally immersed in the moment and free from feelings of anger, fear, or ego.”

Doing calligraphy in the prayer hall at the temple Ryōunji. (© Masterworks)

Many figures from the world of Japanese Buddhism have been impressed by Shōko’s calligraphy. One of her greatest admirers is Kimiya Kōshi, priest at the temple Ryōunji in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, where an exhibition of Shōko’s work is held every year. Kimiya praises Shōko’s work in the highest possible terms: “It perfectly encapsulates the philosophy of sunyata, or emptiness, that is the subject of the Heart Sutra. Her calligraphy looks inspired, as if it might have been written by a Buddha.” At Ryōunji, they rebuilt the main prayer hall to accommodate a huge version of the Heart Sutra that Shōko did to mark her thirtieth birthday. The completed calligraphy, 4 meters tall and 18 meters long, has been called “the biggest Heart Sutra in the world.”

An Empathy with Children

Shōko has written calligraphy at some of the most famous holy places in Japan: historic Buddhist temples like Hōryūji and Tōdaiji in Nara, Kenninji in Kyoto, and Kenchōji in Kamakura, as well as Ise Jingū, the most important of all the country’s Shinto shrines. When she makes appearances to write calligraphy at famous temples and shrines, members of the public often attend. It is not unusual to see parents with Down syndrome children.

A piece of Shōko’s calligraphy at Kenninji temple in Kyoto, next to Tawaraya Sōtatsu’s famous painting of the Wind and Thunder Gods, a national treasure. (Photo courtesy of Kenninji)

The young mothers listen to Yasuko’s talk and look on expectantly. Next to them sits Shōko, gently stroking the heads of babies and children on the tatami, or cradling them in her arms.

“When a child is crying, we normally think of what we can do to make it stop. But Shōko comes close to the child and strokes them on the head. She feels an enormous empathy, and sheds tears herself with them,” says head priest Kimiya. “Even more than her wonderful calligraphy, she has a lot to teach us about empathy and human kindness.”

What the Future Holds

Praise for Shōko’s work has also come from the art world. “There’s no doubt about it—she’s a true artist,” says Miyata Ryōhei, a metalsmith who has served as president of the Tokyo University of the Arts and commissioner of the Agency for Cultural Affairs. Senju Hiroshi, a New York–based Nihonga-style painter who has himself created huge works for famous temples including Kongōbuji at Wakayama Prefecture’s Kōyasan, says he feels in Shōko’s “tear-stained Heart Sutra” calligraphy the “same impact and strength that you find in the work of master sculptors like Constantin Brâncuşi and Isamu Noguchi.”

At the end of the film, Senju explains why Shōko’s calligraphy is exactly the kind of art we need in our present age, when life itself sometimes seems to atrophy and wilt under the weight of anxiety and stress. To the spectators who have watched warmly as Shōko writes her calligraphy, these challenging words seem to come like a splash of cold spray from one of his famous waterfall paintings.

The film is well worth seeing to hear what Senju has to say. Words of encouragement and praise from a more senior artist to his junior, his message will surely have an effect on audiences too, inspiring in them an interest to see how Shōko lives her life in the years to come, and an excitement to see what unseen works lie ahead in her future.

Shōko and her mother offer prayers before a calligraphy session in the prayer hall at Ryōunji, decorated with the “world’s biggest” Heart Sutra, in Shōko’s calligraphy. (© Masterworks)

Tomo ni ikiru: Shoka Kanazawa Shōko (Living Together: Kanazawa Shōko, Calligrapher)

- Calligrapher: Directed by Miyazawa Masaaki, 2023

- Cast: Kanazawa Shōko, Kanazawa Yasuko

- Produced by Kamata Yūsuke, © Masterworks

- Running time: 79 minutes

- Website (in Japanese only): https://shoko-movie.jp

(Originally published in Japanese on June 2, 2023. Banner photo: © Masterworks.)

calligraphy documentary Kanazawa Shōko Down Syndrome calligrapher