Manga Media and Content in Postwar Japan

“Moonlight Mask” and the Birth of the TV/Manga Media Mix

Culture Entertainment Manga- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Origins of a TV Sensation

In February 1958, just five years after television broadcast began in Japan, the television series Gekkō Kamen, known in English as Moonlight Mask, hit screens. The titular hero hid his face with a white mask and sunglasses as he raced through the streets on a motorcycle with cape fluttering behind. The Moonlight Mask’s slogan as he fought injustice was, “Hate not, harm not, forgive all.” The character overall was something of a “Japanese superman,” with additional influence from historical novels.

The series premiered on Radio Tokyo Television (KRT, now operating as TBS), running for 10 minutes six days a week, Monday to Saturday, from 6:00 pm. When the clock struck six, children would vanish from Japan’s playgrounds and streets, gathering at home or at friends’ places to sit in front of the small screen. Gekkō Kamen merchandise was also a hit. Children would tie towels around their necks as makeshift capes, decorate their bicycles like the hero’s motorbike, and spin toy pistols on their fingers.

Kawauchi Kōhan, who went on to earn fame as a songwriter in later years, wrote the scripts. Most of the production staff were beginners, and even the director, Funatoko Sadao, was on his first series. Still, the show as a huge hit, earning a record 60.7% viewership. It ran until July of 1959, bouncing between various time slots. The first adaptation for the big screen, which was considered the king of popular entertainment at the time, came out in 1958. Star Ōmura Fumitake took the lead role in a total of six films rushed out by the end of 1959.

Another Hit in Manga

Catching that wave of popularity, monthly kid’s magazine Shōnen Club soon began serializing a manga version. The artist was new star Kuwata Jirō, who had drawn a hit for a rival magazine. Serialization started about three months after the broadcast kicked off. The editor who had spotted the program’s potential was right on the money, and the comic helped Shōnen Club skyrocket. The series was also a success in paperback, a relative rarity at the time.

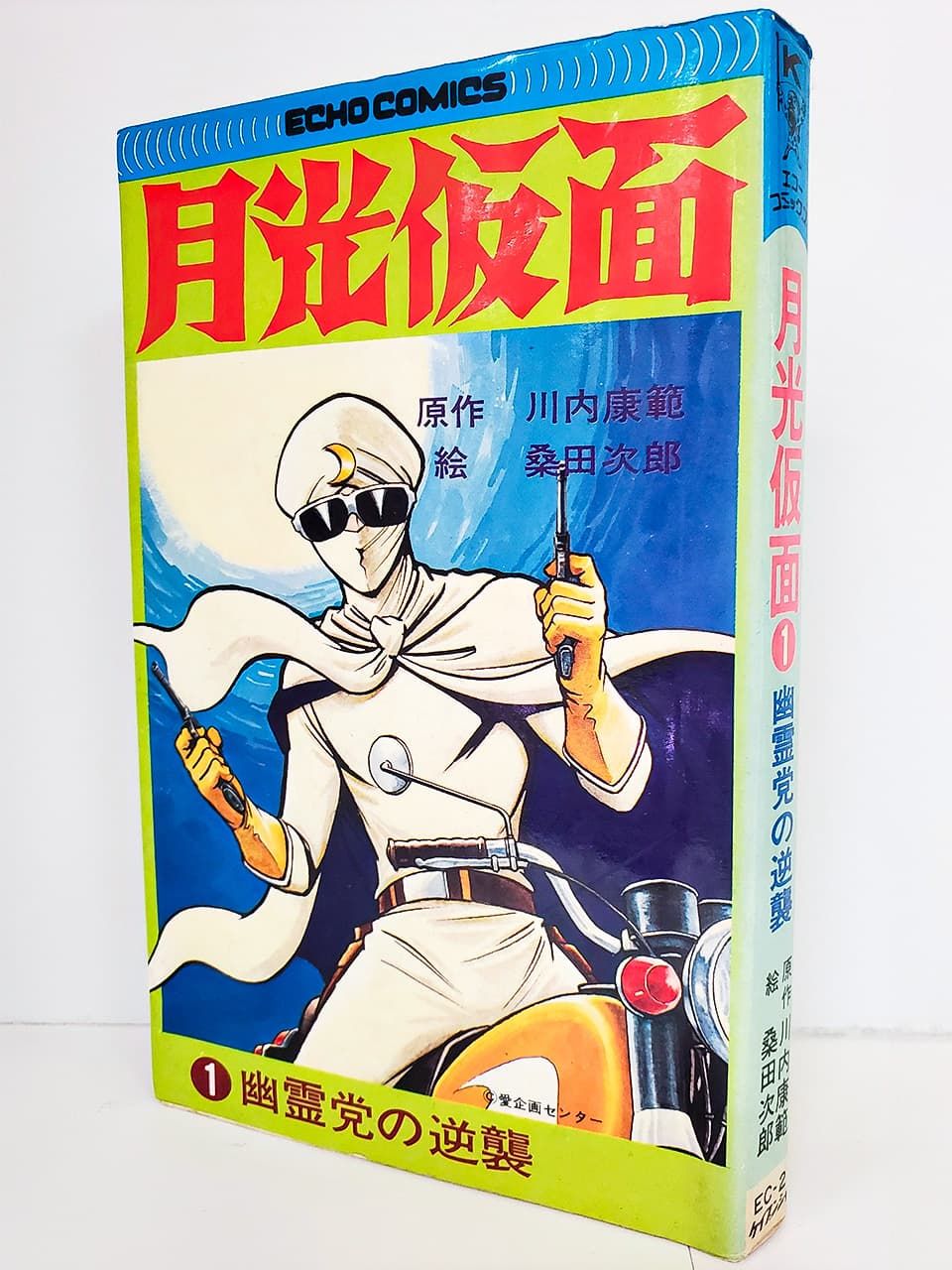

A paperback version of the Gekkō Kamen manga. (© Nippon.com)

As the battle over readership grew more frenzied, rival magazines began to appear, and many even began to copy the TV-to-manga adaptation formula. Other television channels also saw Gekkō Kamen’s success and began producing their own programming for children, so both TV and children’s magazines joined in on the battle royale of tie-ins.

For example, around 1960 both NTV’s Yūsei Ōji (Planet Prince) and Fuji TV’s Kaiteijin 8823 (Submariner 8823, or “Hayabusa,” using a goroawase pronunciation of the numbers) were adapted in Kōbunsha’s Shōnen magazine, while NET (now TV Asahi) series Nanairo Kamen (Seven Color Mask) and National Kid became manga serials in the Kōdansha magazine Bokura. Analysts say that such adaptations helped double circulation for Bokura.

A Virtuous Cycle for Two New Media

There were connections between manga and other media before World War II. The Takarazuka theater troupe adapted the serial manga Shōchan no Bōken (Shō’s Adventure) from the photo magazine Asahigraph into a stage play in 1924. Tōa Kinema then adapted it for the silver screen. After the war, Yamakawa Sōji’s Shōnen Ōja (Young Men’s Champion) went from a street-side kamishibai—a kind of “picture play” storytelling popular with children of the day—to a Shūeisha paperback manga bestseller.

However, Gekkō Kamen was the first example of a manga publisher tying up with another media form for the express goal of building readership, to great success. It showed that there was now a chance for two new forms of media to create synergy and boost each others’ growth.

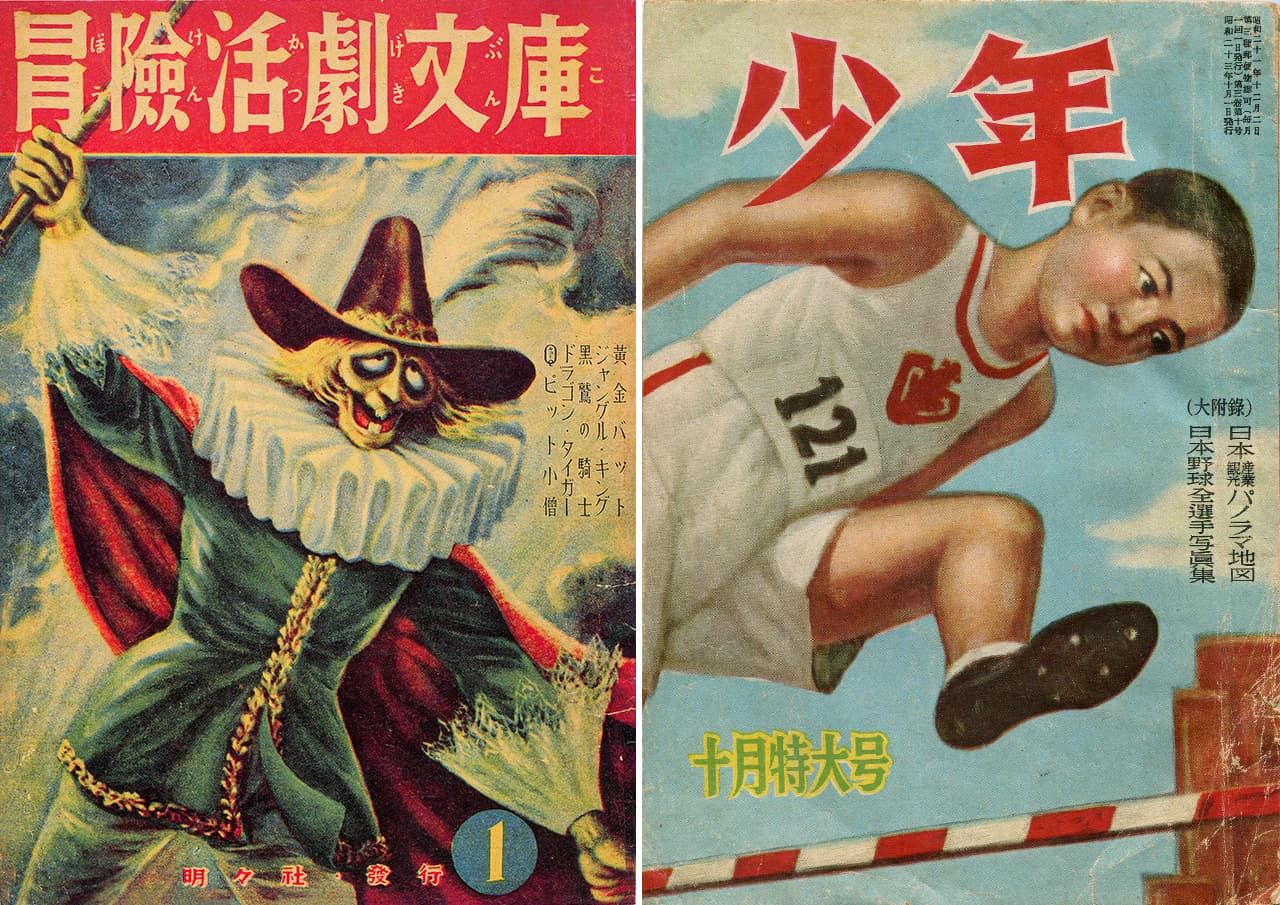

At the time, children’s monthly magazines were in a constant cycle of fresh launches and renewal, and competition grew ever fiercer. Shōnen Club, which had grown with Gekkō Kamen, had started out before the war as Shōnen Kurabu (written in kanji), renaming itself in 1946. That same year was when Kōbunsha founded Shōnen and Gakudōsha started Manga Shōnen. In 1948, Meimeisha’s Bōken Katsugeki Bunko, which later became Shōnen Gahō, joined them, and in 1949 Shōnen Shōjo Bōken Ō and Omoshirobukku appeared on bookshelves. Girls’ magazines also appeared, with Shōjo Bukku (now Ribbon) coming in 1951, and Nakayoshi starting in 1955. It was a free-for-all.

Children’s magazines battled it out over reader numbers by adapting television series into manga. (© Nakano Haruyuki)

All the magazines centered on short stories, nonfiction articles, and photo features of movie and sports starts, with manga relegated to a supporting role. A September 1955 manga journal report states that manga only accounted for about 20% of the content in magazines targeting children. That truth is, though, that publishers often attached separate booklets, around 36 pages long, of manga to their magazines.

Public opinion held that manga was of lower status than narrative fiction or photo layouts, with some considering the style mere “kid’s stuff.” It proved enormously popular, though, and soon became an essential weapon in the industry’s sales battles.

A selection of manga booklets that came attached to children’s magazines. (Courtesy Nakano Haruyuki)

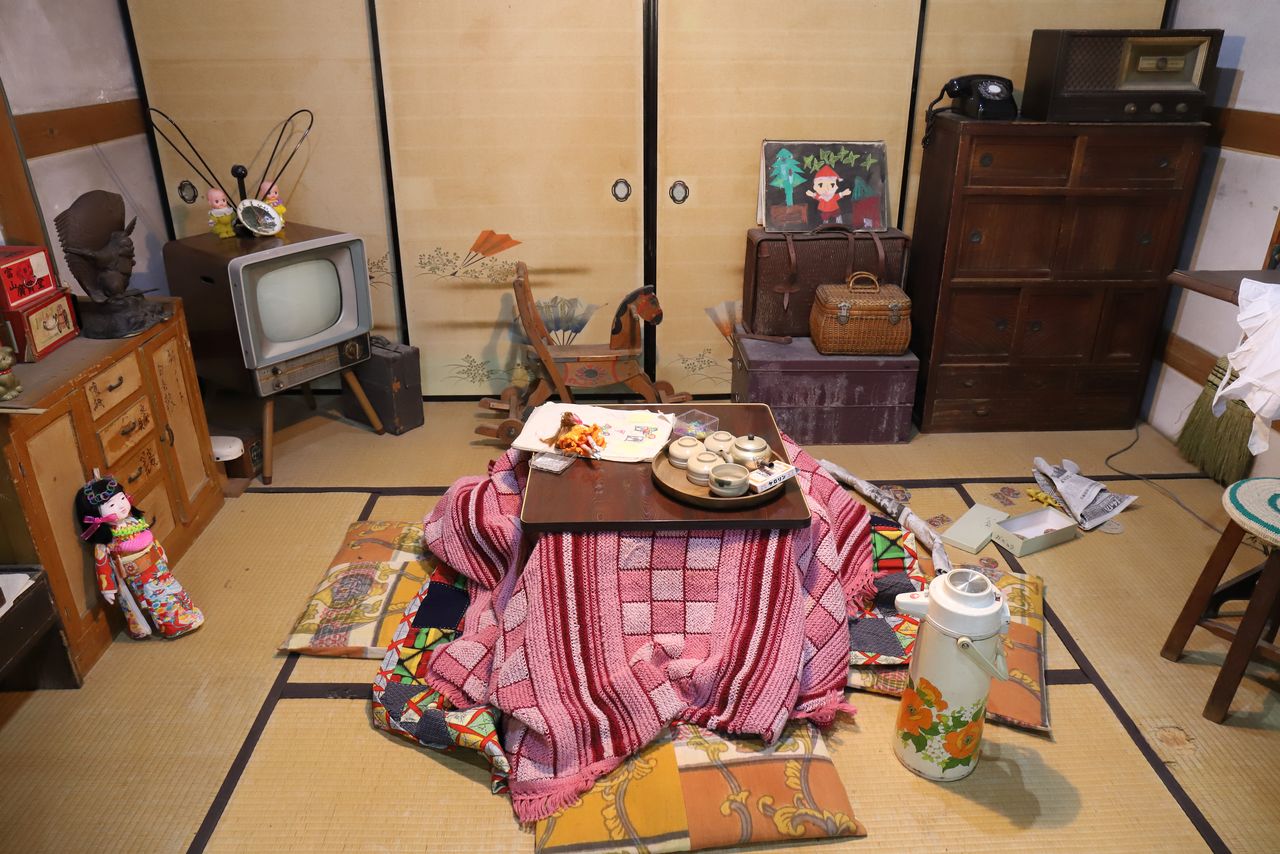

Television was also seeing a huge jump in growth. When broadcasts began in 1953, there were only 866 reception contracts with NHK. Most people watched TV through the sets put out in public locations, like those on streets in front of train stations. Two years later, when KRT began operations, NHK contracts numbered 100,000. The next year, in 1956, stations opened up in Osaka and Nagoya, kicking off a nationwide TV rush. NHK contracts surpassed 1 million in 1958, and construction on Tokyo Tower, the nation’s largest broadcast antenna, was finished. The presence of television sets soon dominated home living rooms.

Even so, TV was often derided as “electric kamishibai” and considered of low cultural impact. The country’s five largest film companies signed an agreement to limit the broadcast of old productions and appearances by actors with exclusive contacts.

This is also when the flow of adaptation from manga to TV took off. In 1957, the hugely popular historical fiction manga Akadō Suzunosuke was adapted into a radio play, and then into a live broadcast series by both KRT and Osaka TV. KRT televised Maboroshi Tantei (The Phantom Detective), a manga by the same artist who drew the Gekkō Kamen comics, in 1959. Fuji TV made a series out of Shōnen Jet (The Jet Boy), a detective manga by Takeuchi Tsunayoshi, the artist behind Akadō Suzunosuke. These television adaptations also helped raise public interest in manga.

Synergistic Growth

The coincidental overlap between manga’s sudden rise in popularity with television’s appearance very likely led to rapid development for both.

Both new media forms made full use of their unique visual formats, and shared an ability to be enjoyed at home. Another shared point is that despite their massive popularity, they were widely perceived as lowbrow culture. Manga earned fans by using its position in children’s magazines, or as attachments to them, to both offer adaptations of television content and to offer content for adaptation on television.

Televisions appeared rapidly in Japanese homes in the 1950s. (© Pixta)

Today, nearly 70 years since Gekkō Kamen appeared, manga enjoys a nearly unparalleled position as a content generator, and it is not at all unusual to see it as a source for TV and movie stories.

However, the road from its beginnings in children’s magazines to becoming a fundamental part of the television media mix through anime was a long one.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Gekkō Kamen, the grandfather of all Japanese TV heroes, with young fans. He went on to become a manga star, as well. Taken in 1958 at a Tokyo studio. © Kyōdō.)