Meiji Painter Yamashita Rin and Her Journey of Faith and Art

Culture Society Arts- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Yearning for Art

“If I am to die, then I’ll die. But if I am to live, then I will live my life.” These words by Yamashita Rin, Japan’s first painter of Orthodox Church icons, stuck in the heart of novelist Asai Macate. Encountering them in a diary Yamashita wrote on a boat voyage to Russia, she was moved by their expression of powerful resolve.

Asai Macate: Historical novelist, born in Osaka Prefecture in 1959. Won the Naoki Prize in 2014 for her novel Renka (Love Poem) about the poet Nakajima Utako, also known as the teacher of Higuchi Ichiyō. Other works include Kurara (Dazzling), about Katsushika Ōi, the artistically talented daughter of the painter Hokusai. (Photo courtesy Bungei Shunjū)

Yamashita was born in 1857, the daughter of a samurai in Kasama in what is now Ibaraki Prefecture. She enjoyed art from a young age, and at around 15 ran away from home to become a painter—eager to participate in the dynamic creative world of the Meiji era (1868–1912), when new influences were pouring in from overseas—although she was brought back again. Later, she successfully journeyed to Tokyo to study traditional art forms like ukiyo-e and nihonga, as well as Western-style painting.

In 1877, she enrolled in the first class of female students at Japan’s first national art college, the Technical Fine Arts School. The following year, at a friend’s invitation she visited a Russian Orthodox church in Kanda, Tokyo, where she met the missionary Nicholas, a major figure who was ultimately canonized. Yamashita was soon baptized, and in 1880, Nicholas sent her to study the painting of icons in Saint Petersburg.

Asai’s extensive research for her novel Byakkō (White Light) about Yamashita included a trip to Saint Petersburg, during which she visited the nunnery where the artist learned how to paint icons. “Rin made a painstaking diary of her stay in Russia,” Asai says, “but sometimes she was so downhearted, she simply noted, ‘Feeling bad.’ I had to imagine what had happened and her emotions around the time.”

A Rebel in the Nunnery

Yamashita rebelled against being made to reproduce ancient Greek icons day after day in the nunnery studio. She had set her sights on modern Western art and yearned to study its techniques, so the ancient icons seemed monotonous and immature to her. In the end, she was compelled to cut short her planned stay of five years, leaving after 18 months.

“The icons had been created before the maturation of artistic techniques, so she didn’t want to study them,” Asai comments. “And as she was so naturally gifted, she hated bad art. Despite her limited Russian, she protested with full self-assurance against the nuns who taught her. Meiji women were really tough. Naturally, she was considered to be a difficult student. In the end, the stress affected her physical health, and she returned to Japan in despair. Her relationship with the nuns is generally seen as adversarial, but I’m not sure—and I also wonder about the Russian Revolution. With the suppression of churches and religious communities, nuns faced terrible persecution. What did Rin, who was sixty at the time of the revolution, think about it? There are no materials remaining that would answer that question. I had it constantly in mind, while traveling in Russia.”

There are also no detailed sources on her friendship with Nicholas, says Asai, leaving mysteries in her relationship with the church.

“After returning to Japan, she became the country’s first painter of icons, but she left the church that had supported her studies abroad. Then, she almost immediately rejoined it. I have no idea why.”

At the time, it was difficult for women who had studied overseas to win the understanding of society, and almost impossible for them to stand on their own two feet economically. But Yamashita, a skilled artist, was able to find jobs in Meiji Japan creating illustrations and portraits for translated books, as well as sketches for lithographs. Asai conjectures that financial reasons did not force a return to the church.

“When Rin left the church, there was friction between Nicholas and longstanding believers over the construction of a cathedral in Kanda,” notes Asai. “They urged him that rather than putting huge sums of money into building a cathedral, he should give money to local churches supporting believers suffering lives of hardship.” Yamashita may have returned to the church to back up her spiritual mentor.

Her trust and respect deepened for Nicholas, who learned to speak Japanese with a Tōhoku accent and insisted on the need for Japanese artists to produce icons for the country’s believers.

“He respected Japan’s old customs and words, and the ‘spirit of the Japanese people.’ He didn’t deny the value of Shintō, Buddhism, and Confucianism, and made an effort to study and understand them. There hasn’t been another Russian who loved the Japanese so much. The belief in gods in natural phenomena like forests and the wind is the starting point for all kinds of faith, and such native beliefs in Russia were absorbed into Orthodox Christianity. Nicholas may have felt nostalgia on encountering them.

“He devoted his life to translating into Japanese the Bible and the words for ceremonies and so forth. He was assisted in this task by Paul Nakai Tsugumaro, who attended the Kaitokudō, a school for kangaku [Chinese studies] in Osaka. During the Edo period [1603–1868], kangaku was like the backbone of learning for literary people. Edo culture remains in the language of the Japanese versions of the Russian Orthodox Bible and ceremonies. The Meiji era was a time of shuffling and assimilation of Edo and foreign culture before they were handed down to us today, and Nicholas played a part in this.”

Art as Self-Expression and the Anonymity of Icons

Yamashita earned her living through art, never marrying.

Asai says, “In the Meiji era, Japan established a state system with the emperor at the top, and ordinary households too were based on patriarchy, as the authorities stressed the image of the ‘good wife and wise mother.’ But Rin chose early on to live as an artist. She didn’t want or hope for anything other than to paint pictures. I think it was good of her Ibaraki family to allow her to live like this. You get an idea of what her older brother and mother were like.

“She was a woman with a modern sense of self, and I think that she chose to be baptized because of her fascination with the church as part of Western culture. Then she studied abroad out of a wholehearted desire to learn about art. By contrast, however, icons were essentially unattributed and anonymous, and their artists had to efface the self. As I wrote, all kinds of issues arose. When did her faith first manifest itself? And when did she truly become a painter of icons?

An Icon Lost and Found

The Holy Resurrection Cathedral (Nikolaidō) in Kanda, Tokyo. (© Pixta)

The Holy Resurrection Cathedral (Nikolaidō) that appears in the novel Sorekara (trans. And Then) by Natsume Sōseki and poetry by Yosano Akiko was destroyed by the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923. The four icons created by Yamashita Rin that were in the building apparently burned in the fire that followed the temblor. In 1929, the cathedral was rebuilt following the original Byzantine-style architecture as much as possible.

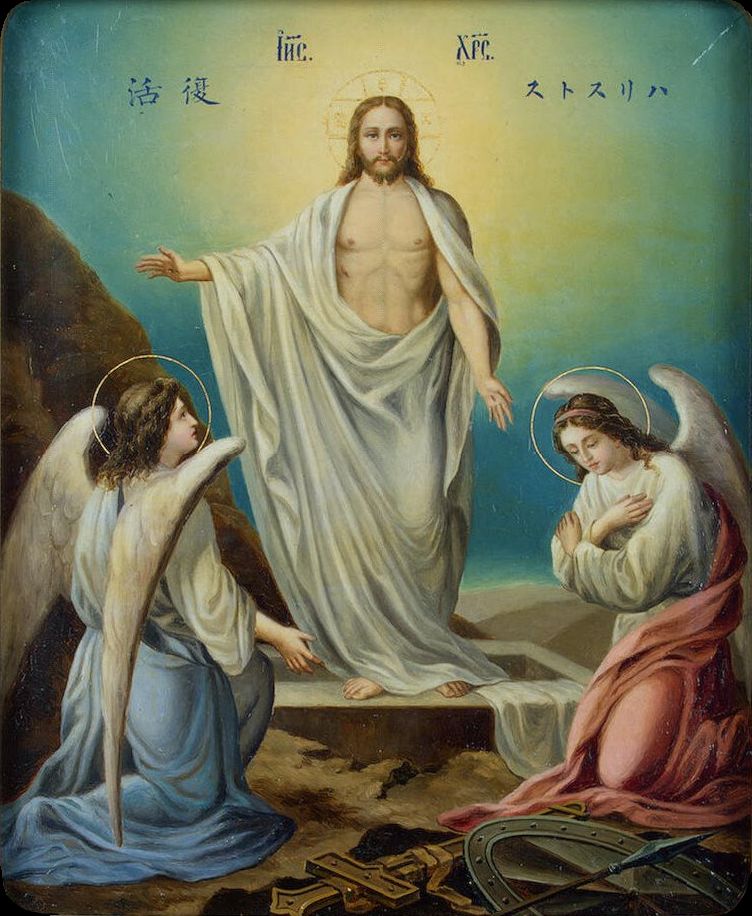

There are, however, still several hundred icons by Yamashita remaining in various churches, such as the Hakodate Orthodox Church in Hokkaidō. While unsigned, years of research by specialists have established those that are hers. Yamashita’s depictions of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary look somewhat Japanese in their facial features and have a general feeling of warmth about them.

The Resurrection by Yamashita Rin, presented to Nicholas II of Russia (then crown prince) during his 1891 visit to Japan.

There is also one of Yamashita’s works in Russia. In 1891, the future Nicholas II of Russia—then crown prince—was presented with an icon of the Orthodox resurrection during a visit to Japan. Following the Russian Revolution, it went missing for many years, but after World War II, it was found to have been preserved by the Hermitage Museum as one of the items left by Nicholas II. Yamashita had visited the museum to make copies of Western artworks during her time in Saint Petersburg. It is moving to think that she made her mark eventually in one of the places she loved.

Her vision affected by cataracts, Yamashita returned to Kasama at the age of 62. She produced no more works, tending her fields and drinking two gō (around 360 ml) of sake each day until her death at age 82.

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com. Banner image: A part of Yamashita Rin’s The Resurrection (1891), currently in the Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg.)