Disaster and Disinformation: Spotting Fake News to Save Lives

Books Disaster Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Lessons from the Noto Earthquake

Almost before the rumbling subsided from the Noto Peninsula earthquake on New Year’s Day 2024, disinformation began to spread across social media. “My family is trapped under a collapsed building and desperately needs help,” cried one post. Ishikawa prefectural police were alerted to the request and dispatched a rescue crew to the scene only to discover that they had been sent on a wild goose chase.

The man who posted the false cry for help, a company employee from Saitama Prefecture, was later arrested by Ishikawa police for obstructing rescue efforts. He admitted to making the fake request, saying that he hoped it would get a big reaction online.

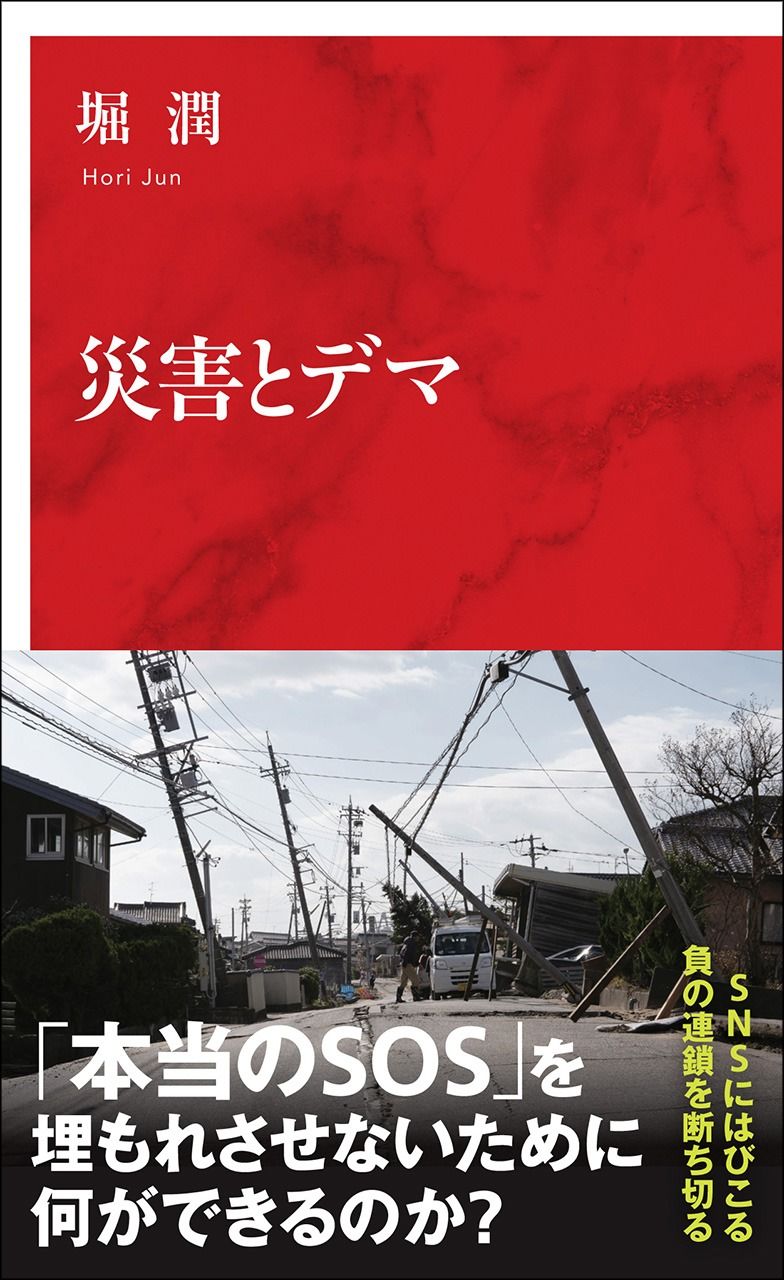

This is one of many incidents journalist Hori Jun deals with in his recently published book Saigai to dema (Disaster and Disinformation), a work that draws needed attention to the consequences disinformation has during the critical hours immediately following a catastrophe.

Hori, a former NHK announcer who has covered major calamities across Japan, describes how the deluge of fake news unleashed in the wake of the Noto earthquake brought attention to “impression zombies” (inpure zombi), a Japanese internet slang term for accounts, particularly on X, making nonsensical comments on popular threads or posting misinformation to increase visibility with the goal of earning advertising revenue. He is strongly critical of users who capitalize on disasters, saying that “it takes a few million views for a poster to earn a meager reward of ¥10,000. Putting others’ lives at risk like that is more than reprehensible.”

Lion on the Loose

Hori uses the string of earthquakes that rattled Kumamoto and Ōita in 2016 as an example of the speed at which disinformation spreads on social media post-disaster. In around a half hour after the initial 6.5-magnitude temblor struck, a photo of a lion standing on a street corner was shared on Twitter with a caption exclaiming that the animal had escaped from the Kumamoto City Zoo and Botanical Gardens and was on the loose in the city. The claim stoked the flames of panic already gripping residents, and within an hour the post had been shared over 20,000 times.

People worried about dangerous beasts roaming the streets phoned the zoo in droves while others vented their fears online, with one user exclaiming that they were too terrified to evacuate their home. To make matters worse, the quake had knocked the zoo’s webpage offline, hampering its ability to refute the claim and quell public concern. It was not until two days later, when a local newspaper ran an article debunking the post, that the story finally subsided.

Three months later, Kumamoto prefectural police apprehended a 20-year-old Kanagawa man for posting the false tweet, marking the first time in Japan an individual was arrested for spreading fake information on social media. The suspect admitted to having made the post as a joke, but charges were eventually dropped after he and his parents apologized in person to the zoo.

In yet another case, Hori describes interviewing a man who posted an AI-generated image of homes purportedly inundated by a typhoon that struck Shizuoka in 2022. The individual had no specialized knowledge of flooding but was still able to generate a convincing image using AI in around one minute, illustrating the power of such tools to spread disinformation.

Forms of False Information

Hori emphasizes how greater public awareness along with the establishment of fact-checking organizations have played a vital role in stemming the flow of fake news. He points to work by the Japan Fact-Check Center, which after the Noto earthquake established five categories to help authorities and residents better identify misinformation.

The first type is a post that uses photos or footage from previous disasters to distort the actual situation on the ground. The second is false calls for help, followed by fake donation drives, unsubstantiated reports of crime, and conspiracy theories (such as unscientific claims of manmade earthquakes or massive radiation leaks).

Hori says that the uneasy mental state of people during disasters makes them more susceptible to the pull of false rumors, stressing that the terrifying power of misinformation is its ability to sow suspicion and distrust by warping the truth. In extreme cases this can lead to persecution of and violence against innocent individuals, such as occurred in Japan when panic fueled the massacre of Koreans in the aftermath of the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake.

Far-Reaching Impact

Hori warns that such atrocities are not a thing of the past but that the toxic mixture of fear and rumors that arise in times of crisis remain a looming threat, especially when amplified through the megaphone of today’s social media. Malicious actors are able to take advantage of social upheaval to spread disinformation on platforms, influencing public perceptions and behavior and undermining social order.

Social media users themselves play a central role in this process by sharing or reacting to fake news posts. At the same time, they are also subject to the impact of disinformation, making them both accomplices and victims. Hori declares that the propagation of misinformation constitutes a secondary disaster by amplifying the effects of the initial event, stressing that “we as individuals need to be acutely aware that we aren’t just consumers of information but are the ones spreading it.”

After the work’s publication, Japan became awash in rumors of an imminent megaquake based on a 1999 manga. While Japanese authorities assured the public that there was no scientific evidence for such a disaster, the prophecy spread on social media and even deterred people in Hong Kong from visiting Japan. The purported date for the megaquake, July 5, passed without incident.

In a society bombarded by nonstop media, Hori’s book is a reminder that more than ever, the public as both consumers and transmitters of information needs to prevent the spread of rumors and fake news so as to limit their impact on the world we all share.

Saigai to dema (Disaster and Disinformation)

By Hori Jun

Published by Shūeisha in 2025

ISBN: 978-4-7976-8154-3

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image © Pixta.)

disaster book review social media books information technology