Japanese Traditional Annual Events

Kisaragi: A Requiem for Broken Needles and Other Traditional Events in February

Culture Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Drumming Up Business

February, traditionally known as Kisaragi, is best known for Setsubun, with its bean-throwing and ogres, but it also hosts a slew of other traditions and holidays dating back centuries. The month is typically a sluggish economic time as spending cools following the extravagance of the New Year. The negative business sentiment is captured in the term nippachi, a phrase written with the kanji characters for the numbers 2 and 8 in allusion to the second and eighth months, both of which feel the drag of major holidays (New Year for February and Obon for August).

In the past, idle sellers looked to divine intervention to enliven business in the form of hatsu-uma, the first “day of the horse” in February. Hatsu-uma is associated with Inari, the deity of rice and cereals known for her fox messengers, and is celebrated at Inari shrines throughout Japan. It is thought to have started in the eighth century as a rite for bringing a bountiful harvest. In the Edo period (1603–1868), the custom took root among merchants, who prayed to Inari for success in commercial matters.

Hatsu-uma falls in either the first or second week of the month. In the past, a variety of other traditional events took place in the run-up to the day, one of the liveliest being the arrival of drum merchants around January 25. These taiko-uri advertised their wares to customers by thumping their drums as they made their way through the streets. Children by their nature were drawn to the clamorous spectacle and would follow the drum sellers, forming a procession that would snake through neighborhoods, culminating at the local Inari shrine.

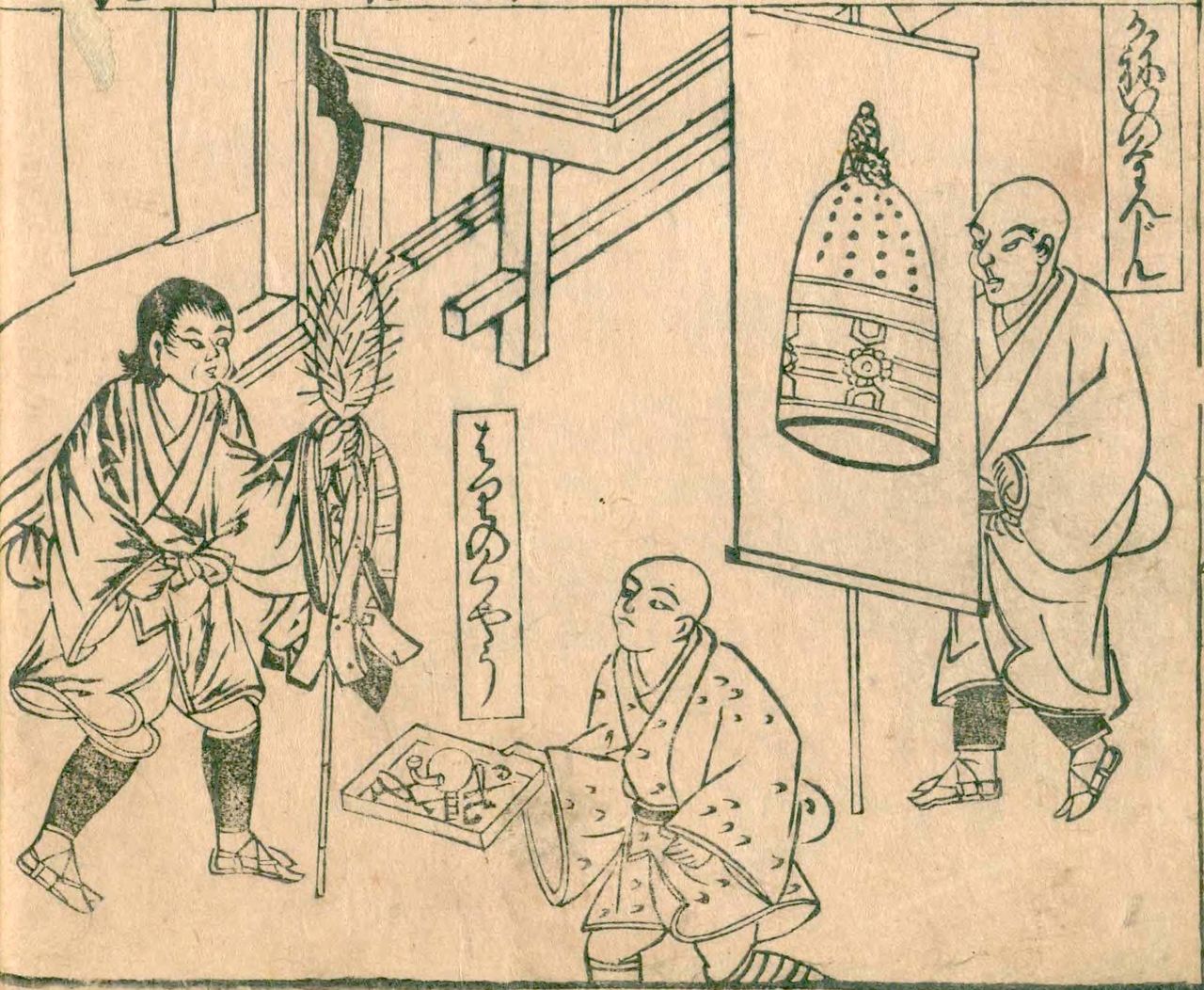

Hatsu-uma was an exciting event for children. Here curious youths eagerly watch a drum seller showing off his wares, as depicted in Kikuchi Kiichirō’s work Edofunai ehon fūzoku ōrai (Picture Book of Edo Customs and Manners). (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Joining the drum sellers were peddlers of nobori, traditional banners attached to bamboo poles (modern-day versions of these can be seen fluttering outside shops, restaurants, and other establishments as advertisements). These were equally irresistible for children, who would brandish nobori to lead the procession of their peers and drum sellers. Such spirited scenes are said to have played out in neighborhoods around the capital, turning hatsu-uma into a favorite occasion for children.

Ema, wooden votive tablets decorated with a picture of a horse, flourished during the Edo period. Those sold at Inari shrines to coincide with hatsu-uma were especially popular among the common classes. A famous print by ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Kunisada I (1786–1864) warmly depicts mothers and their children presenting ema at the Ōji Inari Shrine, which at the time was one of the most popular of the thousands of large and small Inari shrines that dotted Edo (now Tokyo). Ōji Inari remains a favorite location for modern Tokyoites to celebrate hatsu-uma.

Mothers and children—including one carrying a nobori banner—in Kunisada’s Ōji Inari hatsu-uma matsuri no zu, (Hatsu-uma at Ōji Inari Shrine). (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Ōji Inari was also the site of a kite market held around hatsu-uma. Along with being popular toys, the Japanese kite, or tako, was once considered an auspicious item associated with fire prevention. The capital of Edo was famous for its conflagrations and kites expressed the desire to “capture” the wind in order to prevent it from spreading flames throughout the city.

The second and third day of the horse in February, ni no uma and san no uma, respectively, are also important days, although not all Inari shrines observe them. For instance, Kyoto’s Fushimi Inari Shrine, the head shrine of the tens of thousands dedicated to Inari, only celebrates hatsu-uma. There are a handful of shrines that follow traditional reckoning and hold festivities in early March, which corresponds to the second month of the lunar calendar.

Prayers for Needles

A peculiar February tradition still observed today is hari-kuyō, memorial services for used sewing needles. These requiems take place at dedicated shrines and temples as well as schools where sewing is taught and typically involve sticking blunt, broken, or otherwise unusable needles in a large slab of tōfu.

Bent and broken needles are put to rest in tōfu. In some services, gelatinous konnyaku stands in for bean curd. (© Pixta)

Hari-kuyō is observed on February 8, a day traditionally marking the return to regular work routines after the hustle and bustle surrounding the New Year. The custom, called kotohajime, is rooted in agricultural society, but sewers and seamsters, who would have been busy year-round, used the day off to pay respect to the central tool of their trade.

An illustrated dictionary of occupations first published in 1690 titled Jinrinkinmōzui, describes a more sinister side to hari-kuyō. According to the work, unscrupulous people would use the memorial service as a pretext to bilk female servants and young girls of money, threatening that damnation awaited them unless they showed reverence and made offerings for their broken needles.

A man, presumably a needle maker or tailor, with a doll used for collecting old needles joins two priests conducting hari-kuyō services, as depicted in Jinrinkinmōzui. Young women were often pressured into paying for such memorial services. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Many temples and shrines still observe hari-kuyō, including Tokyo’s Sensōji, Nagoya’s Wakamiya Hachiman Shrine, and Osaka’s Taiheiji. Among the most prominent is Awashima Shrine in the city of Wakayama. The shrine is associated with Sukunahikona, a diminutive deity of medicine and healing, and is purported to be the origin of the rite. Unlike other shrines, needles are not placed in tōfu but collected, ritually purified, and buried in a “needle mound” (harizuka).

It is unclear when tōfu replaced needle mounds, but bean curd became the typical receptacle as devotees of Awashima, called Awashima gan’nin, spread the custom to Edo and other parts of the country. Fittingly, the hari-kuyō ceremony at Sensōji in Asakusa takes place at a small hall, the Awashimadō, suggesting a link with far-off Awashima Shrine.

The Awashimadō at Sensōji. (© Pixta)

Dolls for Sale

Hinamatsuri, Japan’s doll festival on March 3, is one of five seasonal festivals (sekku) observed in Japan. In preparation for the event (on the third day of the third month in the traditional lunar calendar), vendors of hina dolls would display their goods at markets called hinaichi. The most famous of these in Edo was the Jikkendana market in the Nihonbashi district. During much of the year the area housed shops offering daily goods and other items, but from the twenty-fifth day of the second month, doll sellers would line the street.

Customers peruse boxes of hina dolls at the Jikkendana market, as depicted in Katsushika Hokusai’s Ehon azuma asobi (Picture Book of Edo Amusements). (Courtesy the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room)

The seasonality and specialty of hina dolls allowed shops to dictate prices, and some accounts describe merchants making small fortunes during the brief period the market was open. Haggling was also a common practice, though, suggesting that customers were not completely at the mercy of doll sellers.

February, although more subdued compared to the event-filled New Year period, still boasts a number of notable traditional observations, including several dear to merchants, children, and women.

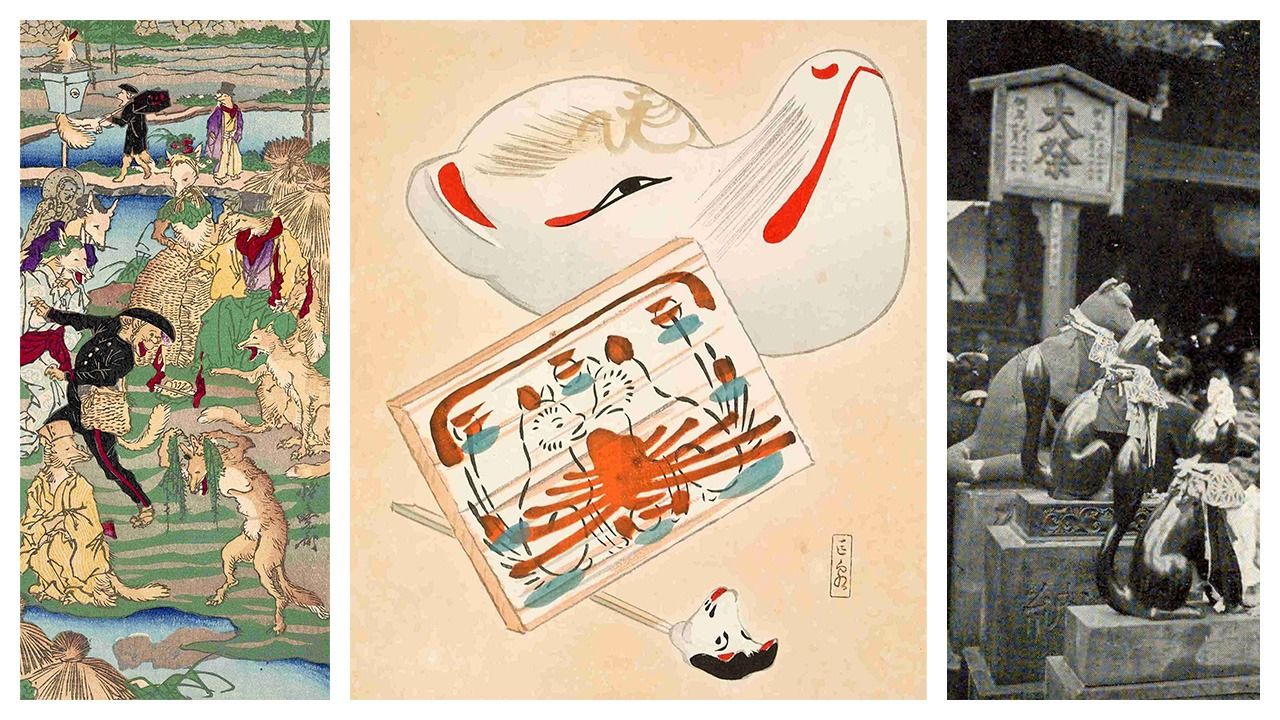

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner images [from left]: Foxes congregate at an Inari shrine during hatsu-uma in Utagawa Hiroshige III’s Famous Places in Tokyo, Ōji Inari Shrine [courtesy of the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room]; ema and other hatsu-uma items featuring foxes in Kawasaki Kyosen’s Collected Illustrations of Japanese Toys [courtesy of the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room]; and fox statues on display at the hatsu-uma celebration at Toyokawa Inari in Tokyo’s Moto-Akasaka neighborhood in Tōkyō no shiki, nenchū gyōji to kinkō no kōrakuchi [courtesy National Diet Library].)