Japanese Traditional Annual Events

Uzuki: Celebrating the Birth of Buddha, Wisteria Viewing, and Other April Traditions

Culture Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Festival of Flowers

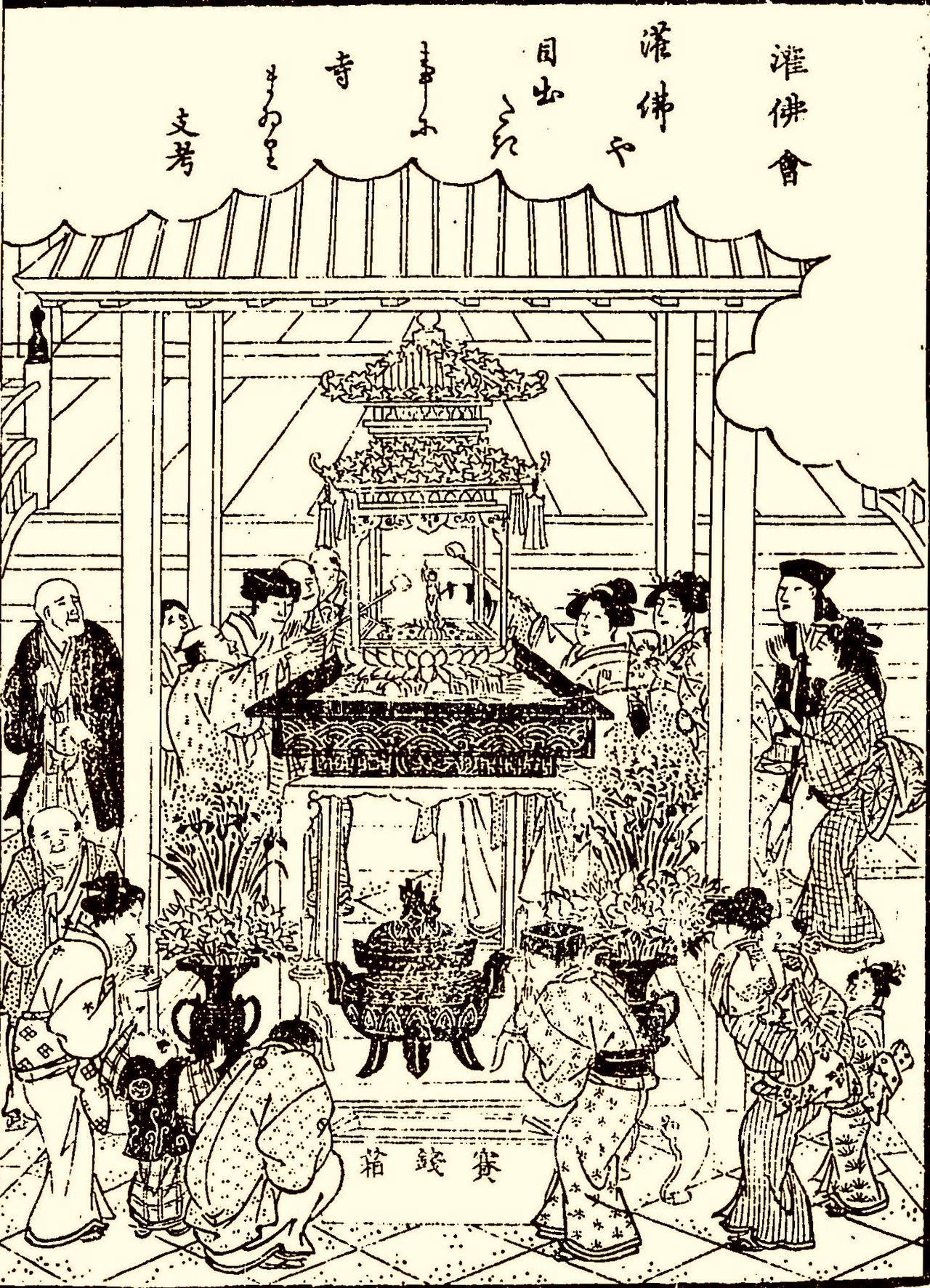

In April, Buddhist temples across Japan celebrate kanbutsue to commemorate the birth of Siddhartha Gautama, founder of Buddhism. The festival features small shrines called hanamidō (flower halls) that worshipers decorate with flowers, typically peonies and Japanese irises. From this, the celebration has also come to be known as hanamatsuri, or flower festival, an appellation coined by a Jōdo Shinshū priest in the Meiji era (1868–1912).

Worshipers celebrate kanbutsue by decorating a hanamidō with peonies in a print from the Tōtosaijiki, a work recording different seasonal events in Edo (now Tokyo). (Courtesy National Diet Library)

The hanamidō consists of a basin of water containing a statue of the newly born Buddha. Visitors “bathe” the image with amacha, a naturally sweet herbal tea made from a variety of hydrangea, while praying for the health of children and the general wellbeing of themselves and society.

During the Edo period (1603–1868), it was customary for celebrants to take amacha brewed by temples home to make ink with. This was then used to create a charm by writing a special phrase on a piece of paper referring to five great bodhisattvas (godairiki bosatsu), imbuing it with the ability to repel troublesome insects, among other magical properties.

Although kanbutsue is generally observed on April 8, some temples still celebrate the flower festival according to the traditional lunar calendar date, which corresponds to early May by modern reckoning.

Seasonal Tastes

Traditionally, April was a festive culinary time as it heralded the arrival of schools of bonito to Japan’s coastal waters. Hungry residents listened anxiously for to the spirited call of fishmongers announcing hatsugatsuo, the first catches of the season. The excitement over the delicacy was captured in verse by haiku poet Yamaguchi Sodō (1642–1716), who wrote: “The sight of green leaves / the song of the cuckoo in the mountains / the first bonito of the season.” Another haiku poet, Kobayashi Issa (1763–1828), was similarly inspired by the call of fish sellers, writing: “Hearing the cry / I rush in high spirits / chanting katsuo.”

Much sought after, bonito was a pricey treat. Documents from 1812 list the cost of three fish at two ryō and one bu, equivalent to an eye-watering ¥400,000 in today’s money. But bonito was so coveted that it was deemed worthy of “pawning your wife” to acquire.

Bonito long remained a dish enjoyed by the well-to-do, who could afford the exorbitant cost. As the price came down over time, it became a more accessible delicacy. Even at 250 mon per fish, or around ¥7,500 in today’s money, it was a luxury, but one that members of the common class were willing to pay for. The banner image at the top is a famous print by Utagawa Toyokuni III that depicts servants in rear tenements drawn by a fishmonger hawking bonito in a side street. Knowing poorer residents would pay a premium for the fish, vendors gouged buyers and focused their efforts on where they could make the most money. This led Jippensha Ikku, a famed writer of humor and travel tales, to quip that bonito sellers “now snub the rich,” perhaps because they were likely to be more knowledgeable about the appropriate price for the delicacy.

Preparing for Summer

The month of April was traditionally a time to stock up on items needed for the coming sweltering summer months. Homes were open and drafty, and mosquito nets, called kaya, were necessary and much sought after to keep the troublesome insects at bay, particularly at night. Goldfish were also popular seasonal items. Sellers of these and other summer essentials appeared in towns and villages around April to hawk their wares.

From left: A print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi depicts a hungry cat eying a bowl of goldfish. (courtesy Colbase); an image from the work Shokunin-zukushi ekotoba (Illustrated Story of Craftsmen) shows a seller of mosquito nets (courtesy National Diet Library).

Wisterias (fuji) were much admired flowers that bloomed in April, with different locations becoming famous for blossom viewing. One of the best known in the capital of Edo was the Kameido Tenjin Shrine, which boasted a large number of the plants strung along trellises. A passage from a famous guidebook for flower viewing, Edo meisho hanagoyomi, eloquently describes how the blooming wisteria, reflected on the surface of a pond at the shrine, seemed to turn the water purple. People today can still enjoy the sight and fragrance of Kameido Tenjin’s wisteria at the shrine’s fuji matsuri, held each year when the some 50 wisteria on the grounds bloom.

From left: A print by Utagawa Hiroshige II depicting the wisteria at Kameido Tenjin Shrine, from the series Thirty-Six Views of the Eastern Capital (courtesy National Diet Library); Wisteria and Wagtail (Fuji sekirei) by Katsushika Hokusai (courtesy Colbase).

Another seasonal pleasure was freshwater clams. In Edo, those caught near Narihira bridge, which spanned a tributary of the Sumida River, were especially coveted. Crowds coming to view wisteria would purchase the succulent items at stalls set up among the trellises.

For those in the upper echelons of society, April marked the seasonal change of wardrobes, called koromogae. The practice originated at the imperial court in Kyoto, with the first of April being when heavier garments containing cotton were changed for lighter, lined kimonos known as awase. During the Edo period, members of the warrior class were expected to conduct koromogae several times a year. The practice spread among the other classes, although only those of means observed it as most common people lacked the resources to purchase more than a few articles of clothing.

It is said that koromogae changed the atmosphere of neighborhoods overnight. One can get a sense of this today when students swap their uniforms, typically in June and then again in October, offering a traditional reminder of the changing of the seasons.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A print by Utagawa Toyokuni III depicts women gathering to buy bonito from a fishmonger. Courtesy of the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room.)