Japanese Traditional Annual Events

Satsuki: Children’s Celebrations, Fireworks, and Other May Traditions

Culture Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Carp Swimming in the Wind

May is traditionally a time to celebrate the health and wellbeing of children. Today families observe the national holiday Children’s Day on May 5, which is rooted in the ancient festival tango no sekku.

One of five seasonal festival based on customs originating in China held on auspicious days throughout the year, tango no sekku was first celebrated in the Nara period (710–794). It became associated with male children during the Kamakura period (1185–1333) through the influence of the military class. A vestige of this is found in one of the festival’s main symbols, the iris or shōbu, which is a homonym for words meaning “battle” and “militaristic spirit.” While tango no sekku has become a celebration for all children, it remains traditional for families to display dolls dressed in military regalia or decorative samurai helmets that symbolize strength and courage.

These customs spread from samurai families to the rest of society, becoming common among all classes during the Edo period (1603–1868). Townspeople and others began to mark the festival by flying koinobori, colorful windsocks shaped like carp. The fish is revered for its strength and features in a popular legend originating in China that tells of a carp that ascends a raging stream to the gates of heaven, where it transforms into a dragon. Like the carp in the tale, the windsocks are believed to instill children with vigor and determination to succeed in life.

Artwork and other documents from the Edo period show other types of banners alongside the windsock, including those emblazoned with drawings of the Japanese folklore characters Kintarō and Momotarō, both heralded for their strength and bravery. Over time, though, these gave way to koinobori as the dominant symbol of the festival.

From left: Children play in front of banners celebrating tango no sekku in the series Kodakara gosechi no asobi by artist Torii Kiyonaga; koinobori flutter over the water in the print “Suidō Bridge and Surugadai” from Utagawa Hiroshige’s series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. (Both images courtesy Colbase)

The custom of flying koinobori has declined as more of Japan’s population clusters in crowded cities. There are efforts to keep the tradition alive, including large-scale displays of windsocks featuring hundreds to thousands of koinobori. The best-known of these are held in Tsuetate Onsen (Kumamoto Prefecture), Tatebayashi (Gunma Prefecture), and Shimanto (Kōchi Prefecture).

Another tango no sekku tradition that remains popular today is soaking in a bath steeped with iris leaves, a practice called shōbuyu in Japanese. The iris is believed to ward off malevolent spirits (jaki), and in the Edo period public bath houses were known to offer iris leaves around tango no sekku, with customers paying a few extra coins for the additions to their bath.

Bathers enjoy shōbuyu in a print by Utagawa Kunisada from Gosekku no uchi, a series depicting seasonal customs. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Boating and Fireworks

One of the great seasonal hallmarks for residents of Edo (today Tokyo) was the opening of boating on the Sumida River. During the season, leisure boats of varying sizes crowded the waters around Ryōgoku Bridge, with the cooling river breezes bringing passengers a welcome respite from the rising heat and humidity. The numerous stalls that sprang up along the nearby avenues added to the festive mood. A fireworks display held on the first day, May 28, was a much-anticipated spectacle that drew spectators from around the city. The tradition continues in the form of the annual Sumida River Fireworks Festival.

The leisure boats, called yakatabune, ranged in size from small, open craft to large vessels with roofs. It is unclear how much operators, often local fishermen, charged to rent out boats, but it was certainly a luxury only the well off could afford. The most affluent Edoites were known to hire large boats for themselves or to entertain friends and business associates, while members of the lower classes could only watch longingly from the bridge or along the banks of the river.

Yakatabune passengers revel under the fireworks in Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s “Enjoying the Cool at Ryōgoku” in the series Famous Places in the Eastern Capital. Among the boat’s passengers are two female entertainers holding shamisen. Hosting such an extravagant cruise would have been a costly endeavor. (Courtesy Colbase)

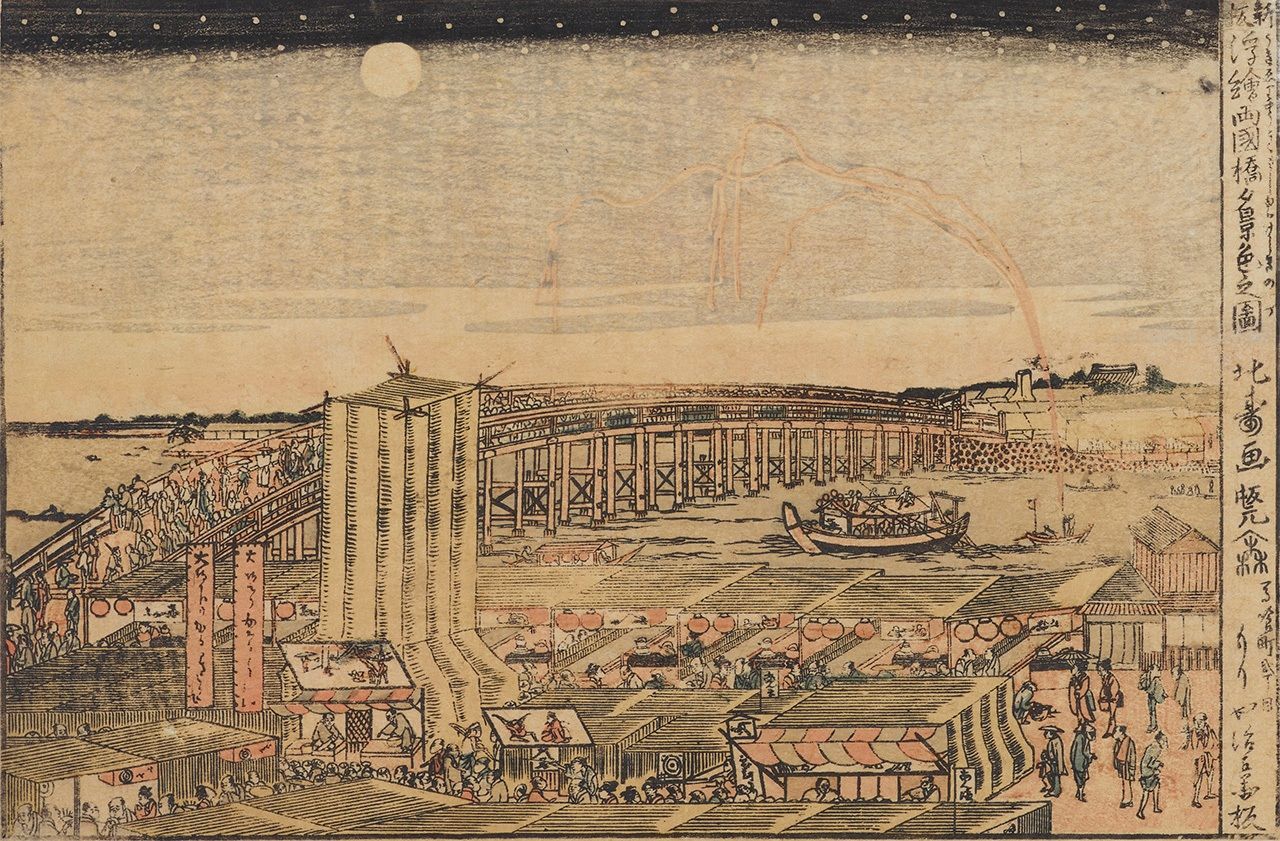

Shōtei Hokuju,a pupil of Katsushika Hokusai, depicts a lively atmosphere of stalls and fireworks along the banks of the Sumida River in “Night Scenery in the Evening at Ryōgoku Bridge” from the series Shinpan ukie. (Courtesy Colbase)

Edo was famous for its fires, with the devastating conflagrations consuming large swaths of the city. Authorities built a wide alley, the Ryōgoku Hirokōji, at the west end of the bridge as a firebreak, which also served as an escape route for residents. In principle, the alley was to be kept clear, but it was known as one of Edo’s most popular night spots, particularly during the boating season when it filled with stalls offering food, drink, and entertainment.

Shōtei Hokuju’s print “Night Scenery in the Evening at Ryōgoku Bridge” (above) shows the tightly packed rows of stalls along the Ryōgoku Hirokōji along with a tall structure showcasing street performers and other entertainers. The hastily built stalls were taken down at the end of the boating season.

Among the stalls along Hirokōji were those selling seasonal treats like tokoroten, jellylike noodles served cold with a sweet sauce or a mixture of vinegar and soy sauce, and biwayōtō, a tea made from loquat leaves, both of which were enjoyed for their cooling properties. There were also vendors selling powder and devices for making shabondama (soap bubbles), an enduring summer activity for children.

A peddler of tokoroten produces the noodles, derived from tengusa seaweed, with the aid of a special utensil called a tentsuki in a print from the series Shokunin zukushi ekotoba by Kuwagata Keisai. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

A traveling salesman offers cups of biwayōtō to customers in Kyokutei Bakin’s print “Biwayōtō seller” in the series Kinseiryūkō akindo kyōkaezu. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Children watch as a seller blows soap bubbles in Katsushika Hokusai’s “Kokuchō” in the series Shinpan daidō zui. (Courtesy Colbase)

It is unclear exactly when the fireworks tradition was first held at the start of the boating season, but most sources date it to 1733. There are conflicting theories as to its roots, however, such as that it started as a requiem for victims of a plague that had ravished the city. Whatever the reason, the seasonal tradition of firework on the Sumida River as well as yakatabune remain a part of life in the capital.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image: Hashimoto Sadahide’s “Summer View at Ryōgoku Bridge” from his Eastern Capital series. Courtesy National Diet Library.)