Honeybees and Swallows: The Changing Landscape of Ginza’s Rooftops

Society Science Culture Food and Drink- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Encounter with an Iwate Beekeeper Changes the Rooftops of Ginza

Lined with venerable shops dating back to the Edo period and luxury brand stores from around the world, Ginza attracts an average of 250,000 people a day. In this bustling urban setting, it is hard to imagine half a million honeybees flitting about overhead.

“When I first started musing about the possibility of raising honeybees on the rooftops of Ginza, people around me debated who should tell me that I was nuts,” says Tanaka Atsuo, senior managing director of the Pulp and Paper Building on the Ginza 3-chome block. He looks back with a wry grin to that time 15 years ago.

The apiary on the rooftop of the Pulp and Paper Building is 45 meters above ground.

After the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble, Tanaka held workshops and seminars in an effort to sustain Ginza’s standing as a thriving hub for innovation. In the spring of 2006, when Tanaka was planning a workshop on food and was seeking an instructor, he ran into Fujiwara Seita, a beekeeper from the city of Morioka, Iwate Prefecture. As it happened, Fujiwara was searching for a building rooftop in central Tokyo to set up an apiary.

Honeybees in Ginza? Tanaka was dubious, but Fujiwara assured him: “You can raise bees here and collect their honey.” Honeybees generally fly in a three-kilometer radius, but within just a two-kilometer radius of Ginza are the Hamarikyu gardens, Hibiya Park, the Imperial Palace, and other green spaces providing ample sources of nectar. Another source are the trees planted along Ginza’s streets, including tulip trees, a variety of horse chestnut trees, and linden. Even better is the fact that agricultural chemicals are not used on these plants.

“You can use the rooftop of our building,” Tanaka offered. After taking a look, however, Fujiwara demurred, saying the rooftop of the Paper and Pulp building was too small for his needs. “Why don’t you give it a try yourself?” he said to Tanaka.

“Ginza has been a shopping district since the Edo period. It would be something if we could actually produce natural honey here,” mused Tanaka. There were some who said it would be dangerous to foster honeybees in a bustling business district, but Tanaka reassured them, pointing out that honeybees do not sting people unless they feel they or their nests are being threatened. It wasn’t long before he got the support he needed. And this is how the NPO Honeybee Project was launched with three fulltime staff members and numerous volunteers including chefs and pastry chefs, bartenders, club hostesses, and others working in Ginza.

From Honey to Sake

The first year, the group only harvested 150 kilograms of honey. But by 2017, they were harvesting 1.6 tons per year thanks to improved beekeeping skills and three additional rooftop apiaries.

Made in Ginza, Ginpachi honey is distinguished by its playfully attractive package designs.

The honey is used as an ingredient in such commercial products as sweets, beers, cocktails, and even cosmetics that are sold in Ginza department stores, restaurants, hotels, and bars. The beeswax is also harvested to make candles that light up the Ginza Church for Christmas and that are sold for charity at the Matsuya Ginza department store.

Pollination by the bees has a major impact on the natural environment around Ginza. Says Tanaka, “When you are working with the roof-top beehives you realize that you are seeing a lot more, and more diverse, varieties of birds. The bees pollinate the plants in the area, causing them to bear fruit, and the birds come to eat that fruit. There is a real ecological cycle here.”

The nectar-gathering season has ended, but on warm winter days, the honeybees still fly out to collect pollen.

To secure more sources for nectar and pollen, greening of the Ginza rooftops has spread, now covering a total area of over 1,000 square meters and comprising a variety of vegetables and fruits, including potatoes, mint, herbs, kabosu (a type of citrus), and kumquats.

These plants, grown from seedlings sent in from growers all over Japan, not only provide sources of nectar and pollen for the honeybees, they are also harvested and transformed into delicious dishes by the master chefs of Ginza, and have led to all kinds of new undertakings, including sake-making.

One example of a cooperative effort leading to a new product that started with Ginpachi’s involvement is the apiary on the grounds of the prime minister’s residence in Tokyo. During the Abe administration, Ginpachi assisted the prime minister’s wife in setting up this apiary. The garden around the apiary was planted with a type of rapeseed, Asaka no natane from Fukushima Prefecture, one of the regions hard-hit by the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident. This in turn led to a project to brew Gohyakumangoku rice, originally a Fukushima sake, at a sake brewery in Yamaguchi Prefecture, where former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s family originated. Members of the Chōshū Tomo no Kai (Friends of Chōshū, an ancient name for the region where Yamaguchi Prefecture is located) participated in a voluntary expedition to Fukushima to plant and harvest the rice used to make the sake. One outcome of these kinds of efforts to support Fukushima, was the birth of a new junmai ginjō sake (made with only rice, kōji, a malted rice starter, and water, with no added alcohol). Named Seiippai, meaning “do one’s best,” this new sake was launched by Ginpachi just prior to the 150th anniversary of the which marked the start of Japan’s modernization.

Liquor produced by Ginpachi. The second bottle from left is Seiippai, a sake, and the second from the right is Ginza Imojin, a distilled sweet potato shochu.

Commemorating the Late Dr. Nakamura Tetsu

With land at a premium in Chūō, the Tokyo municipality where Ginza is located, greening rooftops and building walls has proven to be more economical than building new parks. Still, while many of the buildings in Ginza have lawns planted on their rooftops, not a few are left untended. Ginpachi’s solution was to call for the planting of Satsuma sweet potatoes, a hardy plant that is easy to grow, and providing planters, soil, and seedlings to companies and volunteer organizations. The harvested potatoes are sent to a sake brewery in Buzen, a city in Fukuoka Prefecture, to be processed into a distilled sweet potato shōchū sold under the label Ginza Imojin.

As these examples show, Ginpachi’s business is rapidly expanding to other areas besides the making of honey.

“Ginza is a local community, and like any other community, when you have local products being made for local consumption, you start to see a lot of refreshing new ideas. A product that was not particularly valued before can take on a new face when it’s presented in a new form and with new designs. And when this product is sold in the Ginza department stores it naturally attracts a lot of attention, in turn helping to energize the local community,” says Tanaka.

Ginpachi’s success has prompted more than 100 companies and organizations throughout Japan to also try their hand at urban beekeeping. At the Hagi Iwami Airport in Shimane Prefecture, around 50 apiary boxes set up along the runway are producing some 700 kilograms of honey per year. The airport is working with a number of local businesses to use the honey in developing new products. In Aichi Prefecture, students at the Aichi Commercial High School are making ice cream using fruit and honey from Tōhoku producers hard-hit by the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, and donating part of the proceeds to the Kodomo Mirai Kikin, the Children’s Future Fund.

The Paper and Pulp Building is attracting visitors from overseas keen on learning more about the rooftop apiary business. Two years ago, Tanaka invited Dr. Nakamura Tetsu, a Japanese physician famous for his dedication to helping the people of Pakistan and Afghanistan with the building of hospitals and irrigation canals, to speak about his work at an event held at the Paper and Pulp Building. At that time, Dr. Nakamura talked about his desire to expand his activities to livestock and beekeeping and asked for Ginpachi’s support. Very soon after this, Dr. Nakamura was assassinated in Afghanistan.

His dream, however, is being carried on. It has recently been found that the nectar from citrus trees grown in eastern Afghanistan produces excellent honey. Says Tanaka, “Right now only enough honey is being produced for local consumption, but our hope is that there will soon be enough to export and sell in other countries. Hopefully, the profits from this enterprise will contribute to improving the lives of the people in Afghanistan.”

The Return of the Swallows

The so-called “honeybee effect” is showing up in another unexpected quarter as the “Ginza swallows,” once feared to be on the verge of disappearing, have started to return over the past two years.

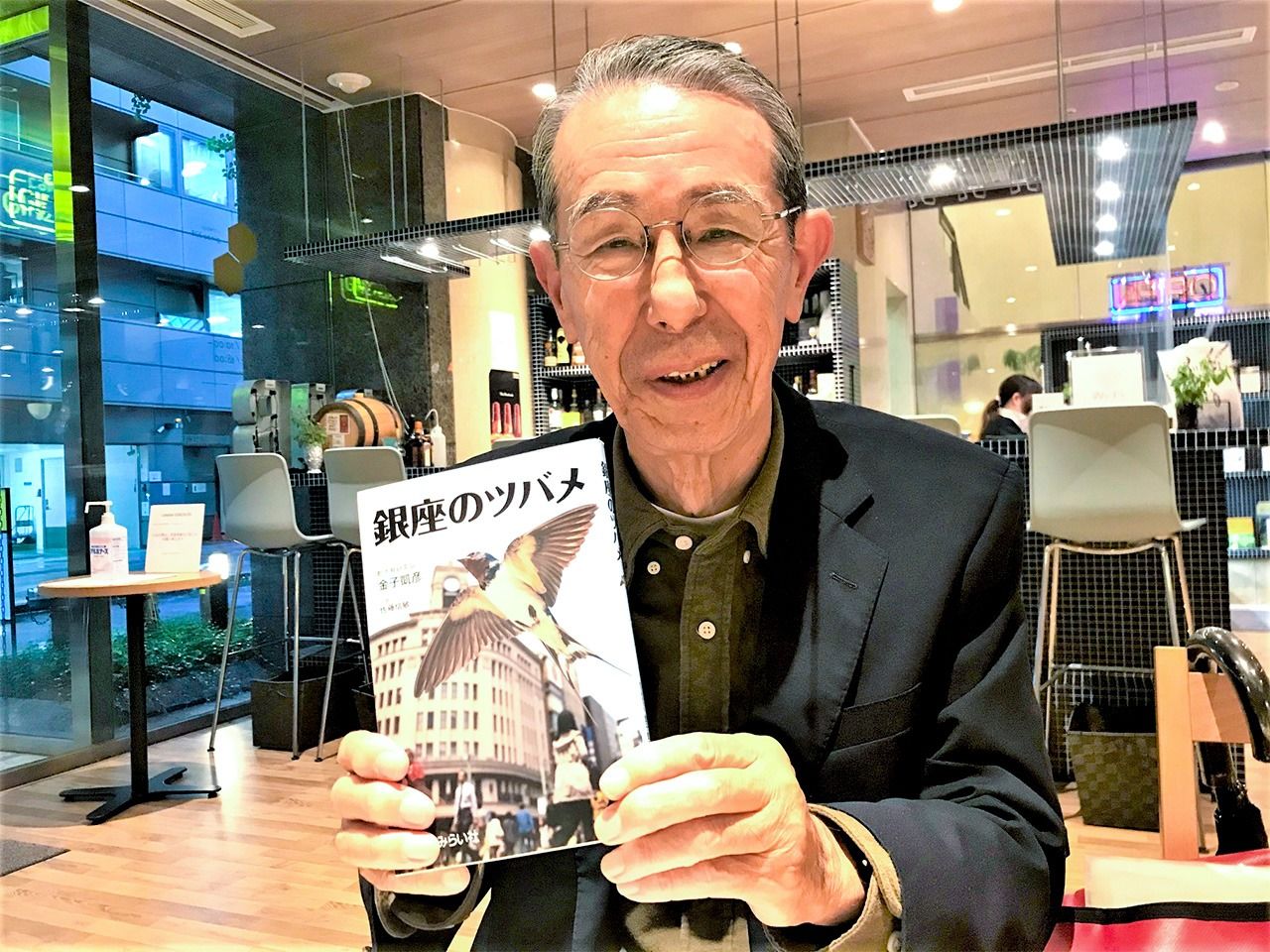

“In 2019, we were able to confirm swallow nests in six locations throughout the Ginza area, a significant increase over the two nests found in 2017. One reason the swallows are returning are the honeybees. Swallows feed on flying insects, usually in a radius of about 300 meters. The honeybees on the rooftop of the Paper and Pulp Building are a great food source for the birds,” explains Kaneko Yoshihiko an authority on urban birds who has been studying the Ginza swallows for nearly four decades.

”We need to preserve the environment in Ginza so that the swallows will return every year,” says Kaneko Yoshihiko, who has studied the birds and their urban habitat for years.

Swallows have been traditionally prized in Japan because they eat the harmful insects that threaten rice crops. Also, because swallows often build their nests in areas where there is a lot of human traffic, they are viewed as harbingers of profitable business. The Ginza swallows were once so famous that they were even featured in a popular song.

Since the 1980s when Kaneko began his research, however, the Ginza swallow population has been steadily diminishing. Back then he confirmed eight nesting areas, but the number has dropped since then. Swallows purposely build their nests under building eaves where there is likely to be a lot of human traffic to protect their young from predators such as crows and sparrows. In recent years, however, many of the old buildings in Ginza have been torn down or rebuilt, depriving the swallows of the shelter they need for their nests. For Kaneko, who launched a project to create artificial nests to attract the swallows, the news that there numbers are growing is very welcome.

Tanaka, on the other hand, who has put all his energy into the honeybee project, has more complex feelings. His fears that the swallows might decimate his honeybees, however, were soon put to rest after he happened to watch a televised film of bees taken by a high-speed camera. When they feel threatened, honeybees respond quickly, suddenly changing direction or slowing down to escape. It was clear only the most seasoned swallows would be able to catch Ginpachi’s bees.

“I realized that this is how the natural food chain works,” says Tanaka. “Both the swallows and the honeybees are surviving as best they can in Ginza. And after all, the swallows were here first.” In the midst of the novel coronavirus pandemic, the Ginpachi staff are taking over the tasks of keeping track of the swallows for Kaneko, who has been unable to visit the Ginza area himself.

Tanaka says the pandemic has shown him how his bees can play a role in society. Honeybees cannot survive in an environment polluted by agricultural chemicals, and because of this they often serve as bioindicators of environmental pollution.

“Society will be a little different after the pandemic dies down. Hopefully, we will change from a society dominated by big things to one in which people can coexist with our little honeybees that are the indices for a clean, pollution-free environment.”

The apiary boxes are opened to check on the honeybees before it gets too cold.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: at left, the Ginpachi staff, with President Tanaka Atsuo at left; at right, worker bees gather around the queen bee. All photos by the author.)