Yaguchi Takao: A Life Lived for Manga

Culture Entertainment Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

I first met Yaguchi Takao, author of the legendary manga Tsurikichi Sanpei (Fisherman Sanpei) sometime in the spring four years ago, when I visited the Masuda Manga Museum in Yokote in the south of Akita Prefecture for an article I was writing. I was a journalist on one of the national newspapers and was working as head of the regional office in that part of the country at the time.

What Yaguchi told me that day and his passionate commitment to his calling as a manga artist made a big impression on me. He had played a key role in encouraging local authorities to get behind the idea of a manga museum in the town where he grew up. As a result of that assignment, I ended up spending much of the next several years researching the ups and downs of Yaguchi’s remarkable life and career, working on a critical biography that was finally completed in December 2020 and published by Sekai Bunkasha as Tsurikichi Sanpei no yume: Yaguchi Takao gaiden (The Dream of Sanpei the Fisherman: A Biography of Yaguchi Takao).

Yaguchi finally lost his battle against pancreatic cancer in November last year, shortly before the book was finally finished. It is a source of bitter regret to me that I wasn’t able to complete the book while he was still with us.

Yaguchi’s beloved Fisherman Sanpei adorns a bridge over the Saruhannai River that flows through the author’s hometown in Akita Prefecture. Photo taken in August 2017 in Masudamachi, Yokote.

There was a reason I chose to include the word yume (dream) in the book’s title. To his dying day, it was Yaguchi’s hope that the government would revive its shelved plans for a National Center for Media Arts, and that the Masuda Manga Museum would become part of this national effort to protect and preserve his beloved manga artwork. My title is an expression of my own hope that his dream will soon become a reality.

The work for which Yaguchi is best known appeared nearly every week for ten years, from 1973 to 1983, in Shūkan Shōnen Magajin (Weekly Shōnen Magazine), one of Japan’s best-selling manga publications aimed at the “youth” market.

The manga chronicles the adventures of a talented young fisherman named Sanpei, who lives with his grandfather in a poor village in a remote part of rural Akita, depicting his adventures in pursuit of exotic fish. The background of the story was based on Yaguchi’s own experiences as a boy fishing in Akita, and the author admitted that Sanpei was a kind of alter-ego. The series, widely credited with having sparked a boom in angling during the years of its serialization, became a huge hit, selling 31 million copies in its bound volume edition and inspiring TV anime and live-action movie adaptations. The anime was shown around the world, and proved especially popular in Italy and Asian markets.

Banker Turned Manga Artist

Yaguchi grew up as the eldest son of a poor farming family. He worked hard, and managed to land himself a white-collar office job with a bank after graduating high school. By the standards of provincial Japan at the time, he had joined the elite. But Yaguchi had loved the work of Tezuka Osamu ever since he was a child, and had never given up his dream of becoming a manga artist himself one day. At the age of 30, with a wife and children to support, he resolved to quit the bank and relocate to Tokyo, where he embarked on a second career as a manga artist.

Perhaps because he was a relatively late starter, Yaguchi continued throughout his career to depict the close ties between the natural world and the inhabitants of the Akita region he knew so well. He never forgot the problems of underprivileged rural communities like the one where he had grown up. His work was marked by a remarkable eye for detail and an astonishing ability to capture nature and animals and make them come alive on the page.

A number of Yaguchi’s old manga have recently been reprinted, including Matagi (1975), which depicted the fading culture of traditional hunters in the Tōhoku region, and Ora ga mura (My Village, 1973), set in a rural village in the decades after World War II. These republished old classics won Yaguchi a new cohort of fans among a younger generation of readers. But Yaguchi hung up his pen after the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami disaster of March 2011, which marked a turning point in his life.

Years later, he confessed that the disaster had filled him with a sense of impotence and despair. Even as he readily volunteered to take part in charity signings with other manga artists, he said he had felt “powerless in the face of this unprecedented natural disaster. Just impotent, as if nothing I could do had any meaning.” The year after the disaster, Yaguchi suffered a personal tragedy when his eldest daughter Yumi died after a long illness.

The bereavement came as an enormous shock to Yaguchi, who had been planning to leave his original artwork and copyrights to his daughter one day and had hoped that she would take care of his legacy after he was gone. And then came more bad news: while tending to his daughter during her final illness, Yaguchi himself was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He went into the hospital for an operation almost immediately after attending Buddhist memorial services to mark 49 days since his daughter’s death.

The whole process robbed him of his physical strength and any appetite for new work. “I used to draw with my right hand, bracing my left elbow to hold the paper I was drawing on. But I lost the strength in my left elbow. I can’t do it anymore; I just don’t have the strength to draw.” Yaguchi had already drafted a new Sanpei story inspired by a fish that lives in Africa’s Lake Tanganyika, but he eventually abandoned the idea and decided to shut down his studio for good.

After retirement, he lived a solitary life of seclusion in his Tokyo residence. Yaguchi was distressed when one of his fellow manga artists died, and his friend’s original artwork came perilously close to being sold off to pay off his debts. “I fought tooth and nail to stop it,” Yaguchi told me. But the experience left a bitter taste, and he continued to worry about what would happen to his own papers once he was no longer here to look after them himself.

“My eldest daughter passed away, and my other daughter left home to get married and start a family of her own. So when I die, there is no one I can leave my artwork and copyrights to. They might be eligible for inheritance taxes; they might be sold off. After I worked so hard to build a career as a manga artist, after I sweated blood to create those stories, the thought of it all being broken up and dispersed God knows where . . . it just doesn’t feel right. The thought is too depressing. So I started to think, if there was a museum or some other facility I could leave them to, then I could rest easy . . . I want the Masuda Manga Museum to be that place.”

Crowds wait to get inside the Masuda Manga Museum on the day of its grand reopening in May 2019

Manga Artwork Fetching High Prices at International Auctions

In recent years, manga has come to occupy an increasingly prestigious position as one of the leading exemplars of the “Cool Japan” phenomenon. One sign of this growing prestige are the high prices paid for original artwork for on the international market.

In May 2018, original artwork for Tezuka Osamu’s Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atomu in Japanese) sold for €270,000 at an auction in Paris. Representatives of the artist’s production company in Tokyo said they weren’t aware of how the artwork, originally created in the mid-1950s, had found its way onto the market. At the time, the original drawings for manga were regarded as just one preliminary stage in the printing process, of little value once the manga had been printed. Tezuka himself apparently gave little thought to keeping track of his artwork once it was printed.

By contrast, many manga artists today struggle to cope with the work involved in storing and taking care of their substantial collections of manuscripts and original artwork. With nowhere to store their collections, some artists have resorted to selling off their drawings to fans for next to nothing. Others simply throw their drawings away. If no relatives are alive to inherit the manuscripts, these papers sometimes simply disappear without trace after the death of the original artist. The artwork can sometimes be assessed for inheritance taxes: the position of the tax bureau and the Ministry of Finance is that a decision is made on a case-by-case basis, depending on previous sales of the artist’s creations and the opinions of experts in the field.

As the artistic valuation of manga increases, it becomes increasingly likely that artwork will be assessed for inheritance tax in the same way as paintings and other types of art. In the case of manga, where the original artwork can easily run into many thousands of manuscript pages, these payments can become astronomical. Donating the artwork to a museum means that it is removed from an artist’s estate and is no longer eligible for inheritance tax.

In 2015, Yaguchi donated around 42,000 of his own original papers and manuscripts to the Yokote Masuda Manga Museum. With support from the Agency for Cultural Affairs, work on preserving and looking after the collection of manuscripts began in earnest.

Changing the Image of Manga

The manga museum was established in 1995 in Yaguchi’s hometown of Masudamachi (since absorbed into Yokote). Yaguchi himself played a leading role in the campaign to persuade the local government of the merits of the idea. When Tezuka Osamu (1928–89), Yaguchi’s great idol, was producing his masterpieces, the prestige of manga as a genre could hardly have been lower. Tezuka fought against this prejudice, frequently appearing on television to advocate for manga as an art form in its own right, and one that deserved respect. Yaguchi continued the fight. In a provincial town where old-fashioned feudalistic ways of thinking were still strong, it took great self-belief and stubbornness to throw away an elite white-collar position as a bank employee and plunge into the ink-stained world of manga.

“I remember once in junior high, a bunch of us were passing around a manga at school and got caught by the teacher. I remember how angry he was. He told us that manga were just trash: something that would have an awful influence on our education and would bring us only negative things, like a pest that would descend on the fields and ruin the crops. Of course, when I grew up I wrote a manga that became a massive hit. I wanted to rehabilitate the image of the genre, so that people would no longer look down on it anymore. That’s what gave me the idea of putting manga into a museum—of setting up a public facility where people would be able to see the original artwork. That’s where you can really sense the living, breathing presence of the author, I think.” Yaguchi told me he didn’t want the museum to be named after himself, because the plan was always that the museum would work to collect and preserve the works of other artists besides himself.

Yaguchi approached other mangaka and asked them to donate their papers to the museum. One who responded was Higashimura Akiko, known for Kurage-hime (Princess Jellyfish), a big Yaguchi fan who says she used to keep copies of Sanpei by her side for inspiration whenever a story required her to depict natural scenery. She remembers when Yaguchi suggested the idea over dinner at his favorite neighborhood sushi restaurant.

“All my original artwork was just piled up in a closet at home gathering dust, so when Yaguchi-sensei offered to take it into the collection of this new museum, I couldn’t have been happier. Now I know that whatever happens, at least my artwork is safe, even if the house burns down. It was a real weight off my mind.”

After building up its collection of original artwork and manuscripts, the Masuda Manga Museum reopened after extensive renovations in May 2019. It is the only place of its kind in Japan engaged in preserving original manga manuscripts and using the artwork to bring the stories and their creators to new audiences. The Yokote city government invested around ¥900 million to cover the costs of the project, and hopes that the museum will help to put the city on the map as a tourist destination. Yaguchi described the museum mission to me in the following terms.

Yaguchi Takao talks about manga in a video panel at the Masuda Manga Museum. (Photo taken October 2020)

“Manga has developed over the years, combining all the elements that make it so entertaining: sadness, excitement, love . . . this museum contains everything you need to learn about what Japanese manga is and what makes it so unique. The original artwork, the manuscripts that authors poured their life experiences and their ideals talents into . . . all this you can see with your own eyes. I hope that the museum will be a place where people can come to learn about manga, and that it will help to nurture and encourage new generations of manga artists into the future.”

Preservation and Digitalization

The museum’s preservation work consists of two complementary strands. As well as preserving the original manuscripts, the museum also converts the papers into digital data for future use. First the original artwork is scanned, sheet by sheet, at a high resolution of 1,200 dpi, more than three times higher than the normal printing resolution of around 400 dpi. It takes around 10 minutes to read one page. Next, each sheet of the original artwork is carefully wrapped in acid-free paper, and then placed inside special acid-free envelopes, each containing one installment of a serial, for storage in a temperature-controlled warehouse facility. Everything is done by hand. The original artwork is used for museum exhibitions, while the digital data can be used for reprints and similar uses. In fact, when Matagi, Yaguchi’s manga about the traditional hunters, was republished in 2017, it was the museum’s digital data that was used as source material for the reprinting.

The “manga warehouse” at the Masuda museum, where original artwork is preserved in carefully climate-controlled conditions. (Photo taken October 2020)

Impressed by this painstaking high-quality preservation work, increasing numbers of manga artists have been signing up to donate their manuscripts. By the end of 2020, around 180 authors had deposited their papers at the museum, which now has around 400,000 items in its collection. Artists like Satō Takao, author of Golgo 13, and Urasawa Naoki, known for Yawara! and 20th Century Boys, have donated their entire collections of papers. Other big-name donors include Kojima Gōseki (Kozure ōkami/Lone Wolf and Cub), Nōjō Jun’ichi (Gekka no kishi/Moonlight Shōgi), and Higashi Akiko. The museum has enough storage space for up to 700,000 items.

A plan to establish a National Center for Media Arts was first discussed during Asō Tarō’s time as prime minister, but the scheme was widely lampooned as a “national manga cafe” and was scrapped when the Democratic Party of Japan took power in 2009. Before his death, Yaguchi often used to look back on the scheme and insist that reviving the idea was more important than ever, a decade on. “If we could establish something like a national manga archive, I would ultimately like the Masuda Manga Museum to become a kind of annex part of that wider facility. We have plenty of space out here, and we could serve a useful purpose as a storage center for manuscripts and original artwork.”

Through acquaintances, I sent copies of my biography to Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide, who also grew up in Akita Prefecture, and Deputy Prime Minister Asō Tarō, a self-described manga and anime obsessive. I received prompt letters of acknowledgement from both leaders, in which they took the time despite the ongoing coronavirus crisis to write about fond memories of Akita and working to gain public support for the idea of a National Center of the Media Arts. I am hopeful that the necessary political steps will be taken to turn Yaguchi’s dream into a reality in the not-too-distant future.

The “Manga Wall” installation at the Masuda Manga Museum in Yokote, Akita. (Photo taken May 2019)

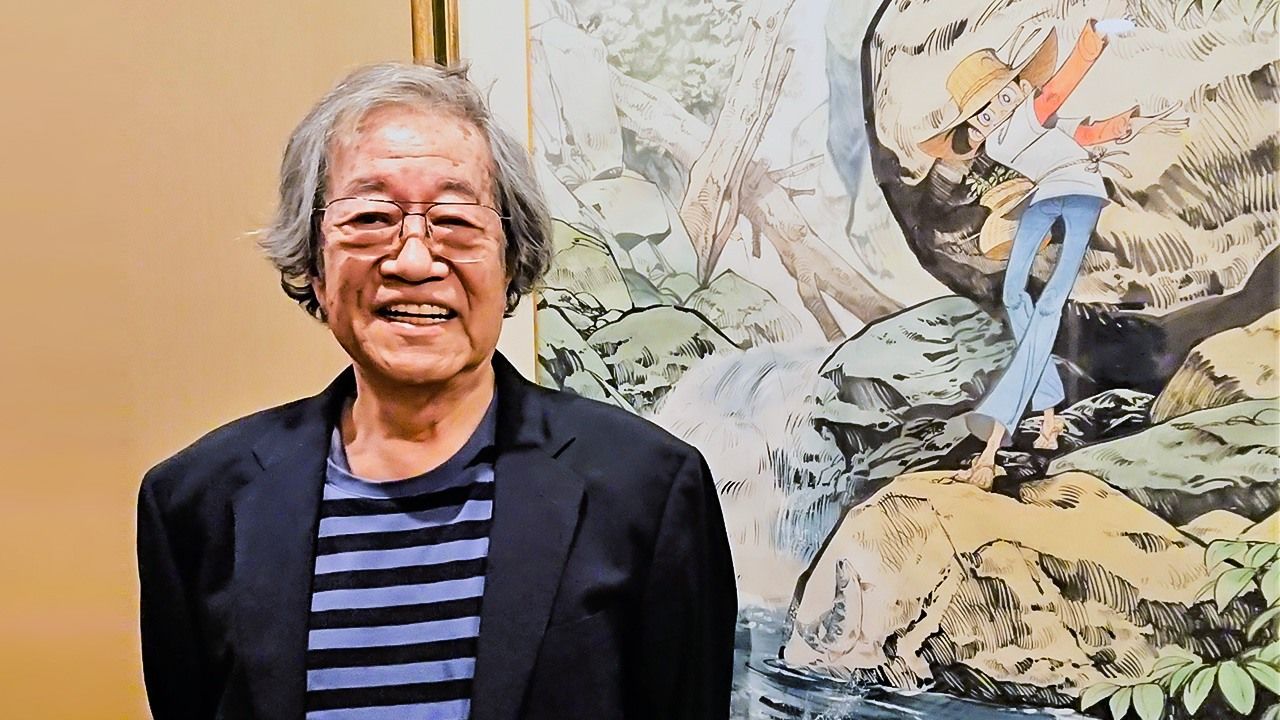

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A smiling Yaguchi Takao, photographed at his home in Setagaya, Tokyo, in January 2020. All photos by the author.)