Mystery Solved: Helmet and Armor at Toyama Temple Determined to Have Belonged to Shinsengumi Leader Kondō Isami

History Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Buddhist temple Kokutaiji in Takaoka, Toyama Prefecture, where I live, is renowned as one of the 15 branches of the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism in Japan. Although tucked deep in the mountains, the modest temple shares the same status as such sprawling Zen centers as Myōshinji and Tenryūji in Kyoto. It has attracted a long list of notable figures over its history, including philosopher Nishida Kitarō (1870–1945) and scholar Suzuki Daisetz (1870–1966), known to many in the West as D. T. Suzuki, who in their youth spent time studying Zen at the temple.

The Sanmon gate of Rinzai Zen temple Kokutaiji. (© Pixta)

More recently, Kokutaiji has garnered attention for the surprising discovery of the helmet and armor of Kondō Isami (1834–68), who commanded the famed Shinsengumi force near the end of the Edo period (1603–1868). The vestments were gifted to the temple by Yamaoka Tesshū (1836–88), an influential retainer of the Tokugawa shogunate. The armor raises questions about the relationship Kondō and Yamaoka shared and how such important relics came to be housed at a secluded temple in the far-off Hokuriku region.

Kondō and the Shinsengumi

In the face of growing resistance by forces loyal to the emperor, the Tokugawa regime in 1863 formed a guard to protect the fourteenth shogun, Tokugawa Iemochi (r. 1859–66), while he stayed in Kyoto. The Rōshigumi consisted of some 230 rōnin (leaderless samurai), with the only requirement for enrollment being that members be able to hold their own with a blade. Kondō, an accomplished swordsman, joined the group. The shogunate placed Yamaoka, who was equally adept with a sword, in charge of supervising the band of warriors, and it is thought that he and Kondō first met through their involvement with the Rōshigumi.

Not long after forming, the group disbanded and its members were ordered back to the capital Edo (now Tokyo). Kondō was among a handful of dissenters who chose to remain in Kyoto. He went on to make a name for himself as commander of the Shinsengumi, a shogunal police force formed by the remaining members of the Rōshigumi that fought against imperial loyalists looking to topple the feudal government. Letters attributed to Kondō show that he corresponded with Yamaoka even after leaving the Rōshigumi.

Kondō would eventually pay for his allegiance to the shogunate with his life. At the January 1868 Battle of Toba-Fushimi on the outskirts of Kyoto, which marked the start of the decisive Boshin Civil War, forces of the new Meiji government led by the Chōshū and Satsuma domains routed those of the Tokugawa shogunate. As the conflict raged, the Shinsengumi’s losses mounted, and members scattered. Kondō was eventually captured near Edo and beheaded as a traitor at age 35.

A Life of Service

Yamaoka served the shogunate to the end, famously helping to broker the peaceful handover of Edo Castle in 1868 to forces led by Saigō Takamori (1828–77). He went on to become an aide to Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) at the behest of his former foe Saigō, serving the young monarch for a decade and having a hand in his moral and scholarly upbringing. In fact, many credit Yamaoka, who on occasions reproached his royal charge for his habit of indulging in late-night drinking sessions, for helping set Emperor Meiji on the ethical path that defined his long tenure on the Chrysanthemum Throne.

After stepping down from his duties, Yamaoka founded the Zen temple Zenshōan in Tokyo’s Yanaka district to commemorate those killed in service of the feudal government. The temple would later garner the patronage of such political notables as Prime Ministers Nakasone Yasuhiro and Abe Shinzō, who would come to practice zazen meditation.

Yamaoka’s decision to gift Kondō’s armor to an out-of-the-way temple in Toyama probably stemmed from his desire to honor the slain warrior without drawing the ire of the Meiji government, which considered Kondō a renegade and would have opposed the idea of him being publicly memorialized. According to Matsuyama Mitsuhiro, the chief curator of the Shinminato Museum in Imizu who has researched the history of the armor, Yamaoka held on to the artifacts until the events of the Boshin War had begun to fade from the public and political consciousness. He then chose Kokutaiji for its connection to the Tokugawa family, whom Kondō had served.

An Unexpected Find

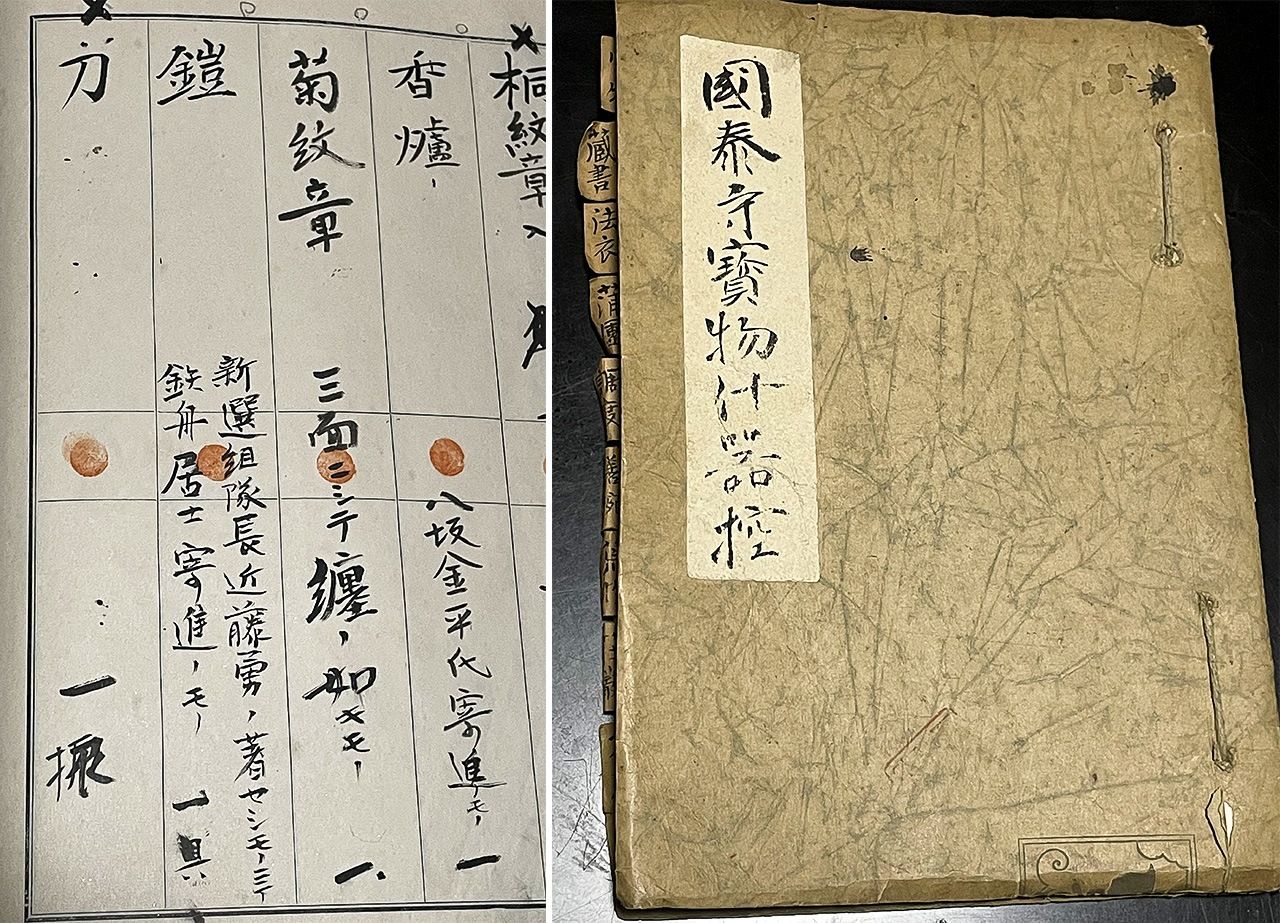

The existence of the helmet and armor themselves was not a mystery. However, any records of who the items had belonged to or how they had come to Kokutaiji had been lost. They had remained shut away at the temple in sealed wooden boxes for years, and had purportedly only ever seen the light of day one or two times. Then in 2020, the discovery of a ledger listing artifacts provided a long-awaited answer to the puzzle. Among the numerous entries in the old document was one describing Yamaoka’s contribution of a helmet and armor belonging to Kondō.

A ledger listing artifacts at Kokutaiji (cover at right). The entry in the second column from the left identifies armor and a helmet belonging to “Shinsengumi Commander Kondō Isami” and lists Yamaoka as the donor.

When an investigation turned up no other sets of armor at the temple, the pieces were determined to be the same ones referred to in the ledger. Kokutaiji then partnered with Shinminato Museum to study the artifacts. An appraisal by an expert revealed that the set had been fashioned in the Edo period using older pieces dating from the Muromachi period (1333–1568).

The helmet bears a round “snake-eye” emblem.

The helmet and armor were thus determined to be Kondō’s. However, he was known for shunning such armaments, and it is likely that he only ever wore the set once in his life.

A Chance to View the Treasures

Kokutaiji enjoyed close relations with the Tokugawa clan during the Edo period, including installing mortuary tablets for each of the shōguns starting with Iemitsu (r. 1623–51), the third head of the shogunate. However, when Yamaoka visited as part of Emperor Meiji’s tour of the Hokuriku region, he was shocked to find the temple had fallen into disrepair, in part due to the anti-Buddhist movement that had flared up at the start of the new era.

Determined to return the temple to its earlier prestige, Yamaoka used his prowess with brush and ink to raise funds, creating over 10,000 works of calligraphy to be sold. It was at this time that he gifted Kondō’s helmet and armor to Kokutaiji.

Yamaoka’s role in preventing war from engulfing Edo is often overshadowed by the meeting of the more celebrated figures of Saigō Takamori and Katsu Kaishū. However, Yamaoka preferred not to seek the limelight. Saigō famously said about Yamaoka that history can only ever be truly described by a person who holds nothing, not life, fame, or fortune, dear. The story of the artifacts belonging to Kondō Isami is just one of countless examples of Yamaoka’s adherence to this ethos.

The helmet and armor will be on display at the Imizu City Shinminato Museum until June 26, 2022.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The front and back pieces of Kondō Isami’s armor kept at Kokutaiji in Takaoka, Toyama Prefecture. All photos © Demachi Yuzuru unless otherwise specified.)