Soothing Power of Traditional Architecture: “Engawa” Writer Chooses Must-See Japanese Verandas

Architecture Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The engawa is a Japanese-style veranda that exists as a space between indoor living and the outdoors. Its roots are thought to lie in awnings of the Heian period (794–1185) that allowed sheltered movement between the various buildings at estates owned by nobles. However, its history as a common feature in homes dates back only about a century.

In general, engawa are divided into two types: nureen, or “open” style on the outside of the house, and kureen, or “closed” versions on the inside. They both bear similarities to a hallway, but their us is less clear cut. It is this ambiguity that is largely behind the disappearance of engawa from Japanese homes, with builders shunning the structures for more practical features.

During Japan’s post-war period of rapid economic growth, urban land prices rose, high-density residences like apartment buildings and condominiums increased, and detached houses became smaller. As living space shrank, a family home needed a kitchen, living room, toilet, and bath, but could do without an engawa. Subsequently, the Japanese-style veranda has gradually faded from Japanese house designs.

I was born in the Heisei era (1989–2019) and grew up in a Tokyo apartment building, and as such I had almost no experience with an actual engawa as a child. To me, they were remnants of the earlier Shōwa era (1926–1989), things you might find in a Studio Ghibli movie or in an episode of the long-running anime program Sazae-san.

The experience that made me an engawa fan was a visit to Kairakuen, one of Japan’s three most famous gardens, in Mito, Ibaraki Prefecture. It is home to the Kōbuntei, which was once a vacation villa for the local lord Tokugawa Nariaki. Sitting on its engawa, I looked out over the beautiful greenery of the garden. Enjoying the feeling, I thought to myself how nice it would be to have an engawa. This got me wondering just how many engawa there were in Tokyo. Once I started down the engawa path, there was no turning back.

The engawa at Kōbuntei. (© Pixta)

In Search of Engawa

I started spending my weekends walking around hunting for engawa. I focused my search on places that seemed likely to have one, like old manors belonging to political or wealthy families that have been preserved as cultural assets, historic inns, or cafes converted from kominka, traditional Japanese homes.

I wanted to find engawa where I could actually sit down, but was disappointed to discover that many were carpeted over with nowhere to sit. I had also assumed that old buildings from the Edo period (1603–1868) would have verandas, but I soon learned that this was not the case.

I launched the website Engawa Navi in July 2013, when I was 23, with the idea of sharing information on the engawa I had visited. I reached out to friends on social media for leads on buildings with engawa, and soon I was visiting places all over Japan.

Sitting quietly on an engawa is a calming, soothing experience. While you are inside a house, you can still take in the atmosphere outside as it changes with the seasons.

A Year-Round Pleasure

My love for Japanese verandas led me to build my own engawa-equipped house in Kamakura.

Partying under the cherry blossoms at a famous hanami spot is great. But imagine the pleasure of sitting on your own engawa, looking quietly out at your own garden cherries, and hearing the call of a bush warbler echo through the air.

In the heat of summer, the engawa is a place to go when the sun has set. You can sit with friends in the evening and enjoy some takeout pizza and beer. There is no need for air conditioning when you sit there in the cool evening breeze after a bath, looking up at the starry sky.

Autumn is the perfect time to set up a little charcoal grill to cook fatty fall saury, and not worry about stinking up the house with fish.

Sanma, a traditional autumn staple, grill over coals.

Even in the cold winter, the sun being lower in the sky means it falls directly on the engawa for longer, keeping it surprisingly warm and comfortable. Hanging futons and cushions to air out on the engawa during winter is likely one way people in the past made clever use of the sun’s energy. And dogs and cats are true engawa lovers for the sunny, breezy atmosphere.

The three years of the pandemic, with its restrictions on going out and the spread of telework, have seen people spending more time at home. Keeping a clear line between work and free time, I step away from the computer and go out to the engawa for lunch or snack breaks. Sitting on the veranda in the sun releases serotonin, which aids in relaxing and relieves stress. I am convinced that “engawa soaking” can have positive effects for employees working remotely.

It is hard to find a house in the city with an engawa, but there are plenty of cafes and guest houses occupying traditional kominka that have them. My aim is to encourage more people to go out on their days off and find out what makes Japanese verandas so nice. I have personally visited over 180 engawa. Below I introduce a few I particularly recommend visiting.

Must-See Engawa

Guest House Toko

This guest house in the Shitaya neighborhood of Taitō, Tokyo, is in a remodeled kominka that is over 100 years old. It is a two-minute walk from Iriya Station on the Tokyo Metro Hibiya line. Sitting on this engawa looking out over the garden, it is hard to believe that such a wonderful veranda is only a 20-minute walk from the bustling shops of Ginza.

https://backpackersjapan.co.jp/toco/english.html

The engawa at Guest House Toko feels like stepping back in time to Japan’s quiet Shōwa era.

Shōwa House Engawa Cafe

Shōwa House is a Japanese residence with Western-style architectural elements located in Nishihokima in Adachi, Tokyo. Built in 1939, it was officially registered as a Tangible Cultural Property of Japan in 2012. It is still used as a residence today, with one section set up as a photo studio and cafe. The garden is a delight, with shidarezakura (weeping cherry tree) in spring and colored leaves in autumn.

https://Shouwanoie.jp/cafe/ (Japanese only)

The engawa café at Shōwa House.

Tsuki to Matsu

This Japanese restaurant in a remodeled century-old kominka in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, is particularly proud of its fresh-made soba noodles and homemade karasumi, a delicacy made of salted and dried mullet roe. Visitors can enjoy a view of the garden through the engawa while dining.

https://whaves.co.jp/tsukitomatsu/ (Japanese only)

The engawa has tatami mats rather than bare wood, which is typical of old residences of politicians and other prominent figures.

Kominka noie Kozuenoyuki

This guest house in the village of Otari, Nagano Prefecture, is in a building dating back some-150 years, to the end of the Edo or early Meiji era (1868–1912). The rural community is deep in the mountains, far from the usual tourist attractions, and offers panoramic views of the surrounding peaks.

http://kominkasaisei.net/ (Japanese only)

The guest house’s engawa is a place for lodgers to gather, set up tables, and get to know each other over breakfast.

Masuya Guest House

This guest house is in the hot spring town of Shimosuwa, where the old Nakasendō and Kōshū Kaidō highways intersected. It was renovated from an old ryokan, a traditional inn, that can be found on Meiji-era maps of the area. The veranda stretches around the entire building for a delightful “full-engawa” feeling.

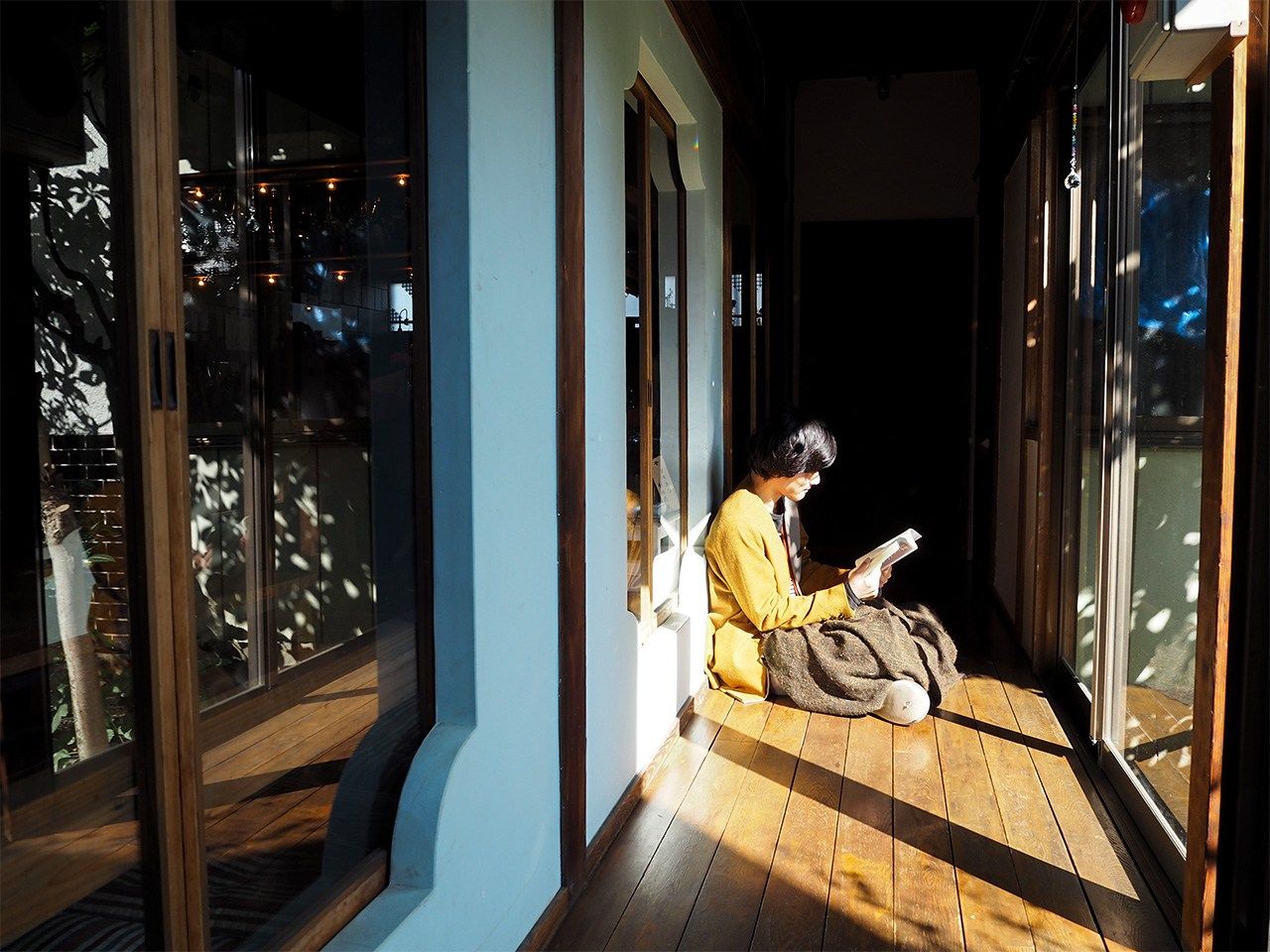

Sun filters into the engawa at Masuya Guest House.

Hanatone

This bagel shop occupies a thatch-roofed home, the former residence of the Maeda family, built over 260 years ago in the mountains of Kobe. The location is quite out of the way, being over an hour and a half walk from the nearest station and with only 10 buses a day serving the nearest stop, but it still has quite a few regular customers who make the long trip.

http://hanatone.jp/ (Japanese only)

Customers at Hanatone can ask to have their bagel heated up to enjoy on the engawa.

Imanishike Shoin

An example of shoinzukuri architecture of the early Muromachi period (1336–1568), this building in Nara is registered an important cultural property. It was once the residence of Fukuchi’in, an important monk at the prominent Buddhist temple Kōfukuji, but was taken over by the Imanishi family, who have run a sake brewery in the city since 1924. From the cafe, visitors can look out over the garden—also an important cultural property—over matcha and Japanese sweets for a moment of pure bliss.

https://www.harushika.com/study/cafe.php

The ancient engawa and garden at Imanishike Shoin.

(Originally published in Japanese. All photos © Naruse Natsumi except where otherwise noted.)