Manga as a Window on Japanese Culture

“Sengoku” Manga a Historical Treat for “Shōgun” Fans

Entertainment Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Samurai: Not Just for Japan Anymore

The Japanese historical miniseries Shōgun, produced by FX together with the Walt Disney Company, was an international hit. It won 18 awards, including Best Drama Series, at the seventy-sixth Emmy Awards.

The series is based on the bestselling novel of the same name, written by British author James Clavell in 1975. It follows the adventures of John Blackthorne, a British sailor whose ship wrecks off the shore of Japan in 1600, at a time when samurai warlords battled for power.

Blackthorne meets the warlord Yoshii Toranaga, with whom he communicates via an interpreter named Toda Mariko. Although the characters are fictional, they are all based on real historical personages, and a real period in Japanese history.

Sanda Hiroyuki, who portrayed Toranaga, on the red carpet at the Academy Awards in Los Angeles on February 13, 2024. The miniseries racked up 9 million views in the first six days after its global release. (© AFP/Jiji)

A Real Japanese Game of Thrones

In ancient times, Japan was ruled by an emperor. However, a warrior class of samurai emerged, and led by a shōgun, seized power in the twelfth century. A series of emperors attempted to regain control, finally succeeding in the fourteenth century. But a warrior named Ashikaga Takauji rebelled, ultimately becoming shōgun. Again samurai ruled the land. However, the Ashikaga Shogunate, as it was known, was riven by internal strife in the fifteenth century. This led to an era known as Sengoku in Japanese—meaning the Warring States period (1467–1568). It was a period of civil war and conflict among regional warlords across the country.

The first season of Shōgun is set in 1600, in the last stages of major conflict before the relative peace of the Edo period (1603–1868). In reality, the warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu became shōgun, putting an end to the national conflict. He is the historical basis for the fictional character of Yoshii Toranaga.

Loyalty is the guiding principle of the samurai in Shōgun. Swearing total fealty to their lord, their philosophy is fatalist. If their fate is ruin, they can defy it by choosing death instead – a ritual known as seppuku.

The fictional characters of Shōgun are shaped by the idealization of what a samurai should be. The samurai of the actual period must have almost certainly have been even rougher in personality.

They were driven by desire, and loyalty was far from an absolute. If samurai felt that they were being treated unfairly, or that their lord was a fool, they would abandon him. What mattered most was getting a chance to test their mettle and gain honor.

Indeed, the samurai of the era of warring states prized life, for they were filled with passion. Such is the philosophy underpinning Miyashita Hideki’s manga Sengoku, which attempts to portray the era with realism. It began serialization in the weekly Young Magazine in 2004.

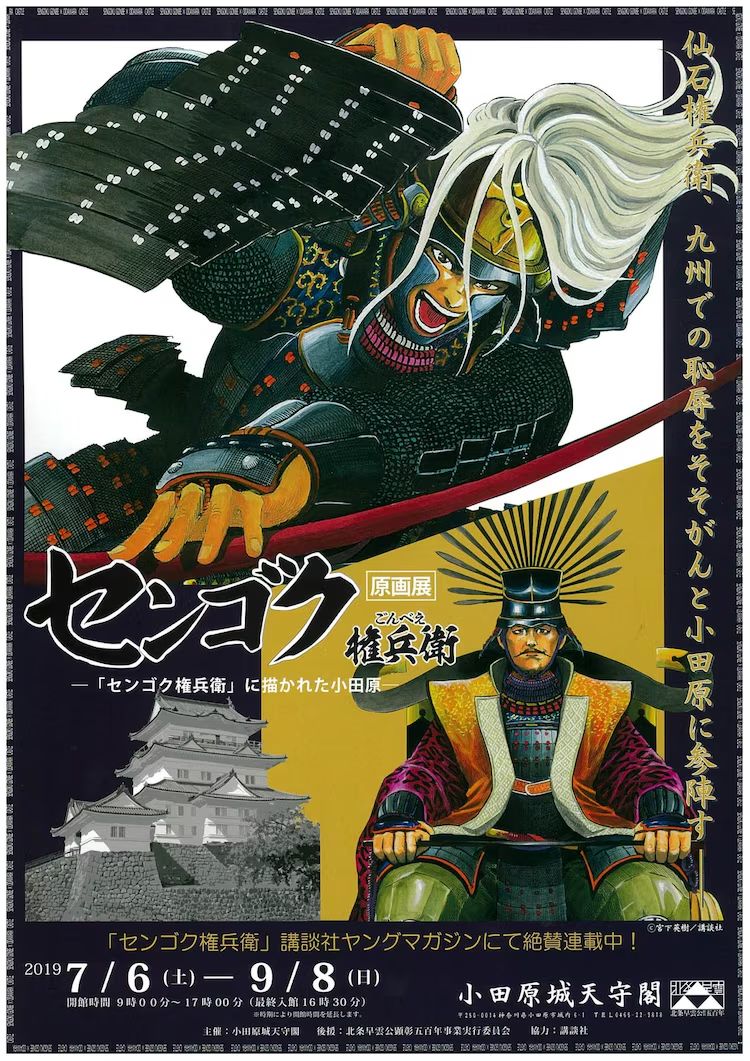

A special exhibition of art from Sengoku Gonbei was held at Odawara Castle in Kanagawa Prefecture from July to September 2019. (© Miyashita Hideki/Kōdansha)

A Survival Guide for the Warring States Period

The manga’s protagonist, Sengoku Gonbei Hidehisa, whose name shares the same pronunciation as the Sengoku period, was born in Mino Province (now Gifu Prefecture). The story of Sengoku is based on real warlords, and faithfully follows history.

The main character never played a leading role in any major battle, nor did he ever gain significant political power. And though he was brave on the battlefield, he also made frequent mistakes, such as failing to receive orders. Had he been alive in the seventeenth century, he likely would have been held accountable for his failures early on and forced to commit seppuku. However, his time was the sixteenth century—right in the middle of the Warring States period.

Sengoku Gonbei fails over and over, but never gives up. No matter the predicament, he keeps going. He achieves greater deeds in the end, becoming a warlord, and even more, “a man who overcame failure like no one else.”

An Edo-period picture of Sengoku Hidehisa from Sengokuke bunsho (Record of the Sengoku Family). (Courtesy Toyooka City municipal government)

Originally a vassal of the Saitō family, Sengoku was recognized by the enemy general Oda Nobunaga (equivalent to the character Kuroda Nobuhisa in the drama Shōgun) and assigned to a unit of Nobunaga’s subordinate, Kinoshita Tōkichirō.

Kinoshita Tōkichirō wasn’t born a samurai; he was of the peasant class. But Nobunaga recognized his skills, and made him one of his clan’s warlords.

The Odas were not a high-ranking clan to begin with. Nobunaga rose to prominence by acquiring territory through his own strategies. In the era, this was known as gekokujō, or “low trumps high,” where talented people in lower positions were recognized for overthrowing incompetent people of higher ranks.

The Charisma to Unify Japan

The historical Nobunaga aimed to unify Japan in a time of strife. He was quick to introduce new weapons such as guns, and create a distinction between farmers and warriors. Nobunaga is said to have held a cosmopolitan, international outlook, and possessed a knack for finances. He also had highly refined artistic sensibilities, harnessing the “soft power” of tea as part of his project to unify Japan.

He was also unusual for possessing a rational outlook, untainted by superstitions. The missionary Luis Frois (1532–97), who knew Nobunaga well, wrote that the warlord “believed neither in the immortality of the soul, nor in judgment after death.”

He had no regard for hereditary authority, whether in the form of emperors, shōguns, or religions, banishing those who were of no use to him, and burning the holy sites and followers of religious orders that defied him. In Sengoku, Nobunaga is portrayed as charismatic but clumsy, blind to the delicacies of human relationships.

The actor Kimura Takuya, playing the role of Oda Nobunaga, responds to cheers during the Nobunaga Cavalry Procession, one of the performances at the Gifu Nobunaga Festival held in Gifu on November 6, 2022. (© Jiji)

Akechi Mitsuhide was a warlord who rebelled against Nobunaga. He was not a hereditary retainer, but a commander who was valued for his abilities and given a prominent position. Nevertheless, he turned on Nobunaga and killed him. Ever after, Mitsuhide was reviled as a “king-slayer,” the most famous backstabber in Japanese history.

Mitsuhide’s daughter was Hosokawa Gracia, represented by Mariko in the drama Shōgun. Her husband was the warlord Hosokawa Tadaoki, a skilled military leader and a distinguished man of culture. However, when Gracia’s father killed Nobunaga, their fate dramatically changed.

Samurai were allowed to change lords and could even serve multiple masters. However, betraying a lord with whom they had a contractual relationship was seen as gravely dishonorable. Moreover, the warlord Mitsuhide betrayed was a highly charismatic leader with a dream of unifying Japan. Tadaoki would normally have had to kill his own wife to protect his position. Instead he sent her into seclusion deep in the mountains.

Yet he had a twisted sense of love. It is said that once he killed a gardener simply for having looked at Gracia, and even showed the severed head to her. Yet, she reportedly continued her meal without flinching. Perhaps seeking escape from this tormented relationship, she converted to Christianity and was secretly baptized. She was held hostage during the lead-up to the decisive Battle of Sekigahara, and under Tadaoki’s orders, she was not allowed to escape. In the end, she chose death.

Taking Control of an Out-of-Control Era

In the end, Sengoku Gonbei’s superior Kinoshita Tōkichirō won the war of succession after Nobunaga’s death, unifying Japan in the process. Later known as Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he is depicted as the Taikō in the Shōgun series.

Nobunaga was a genius with innovative ideas. Hideyoshi also possessed the smarts to understand and further develop Nobunaga’s vision.

The Ōtemon Gate, in Komoro, Nagano Prefecture, is a relic from the ruins of Komoro Castle, which was governed by Sengoku Hidehisa during the Edo period. (© Pixta)

What kind of person was Tokugawa Ieyasu? In Sengoku, the young Ieyasu is depicted as a gambler who deliberately engages in risky battles. Eventually, he grows powerful enough to defeat Hideyoshi in open battle, but he acknowledges Hideyoshi’s talents as superior to his own, and shows a willingness to learn from him.

Ieyasu lacked the originality of Nobunaga or Hideyoshi. However, he possessed the ability to learn, plus the patience to bide his time for opportunities. As depicted in Sengoku, it is these qualities that are necessary for one to assume the title of shōgun.

Seasons 2 and 3 of Shōgun are said to be in the works. The series offers an excellent way for people everywhere to learn about and enjoy Japanese history.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Sengoku ran in weekly Young Magazine from 2004–07. It was later collected in 15 volumes. Including the sequels Sengoku Tenshōki (2008–12), Sengoku Ittōki (2012–15), and Sengoku Gonbei, (2015–22), the series has over 10 million copies in print. © Nippon.com.)

manga Warring States period samurai Manga and Anime in Japan