In Memory of Tanikawa Shuntarō: A Great Poet and Shaper of Literary Language

People Society Culture Art- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Loneliness of Existence

Tanikawa Shuntarō, who passed away in November this year, can be said to be Japan’s most popular poet of modern times. Many poets have won acclaim in the country over the past century or so, including Hagiwara Sakutarō, Kitahara Hakushū, Nakahara Chūya, and Miyazawa Kenji, as well as postwar writers like Tamura Ryūichi, Ibaragi Noriko, and Shinkawa Kazue. However, there is nobody like Tanikawa, who was loved by so many people, and was active as a poet for more than 70 years.

His poem “Two Billion Light-Years of Solitude” was first published in the literary magazine Bungakukai when he was 18, and many Japanese people have read it at least once in their school textbooks or elsewhere. Here is the translation by William I. Elliott and Kazuo Kawamura.

Two Billion Light-Years of Solitude

Human beings on this small orb

sleep, waken and work, and sometimes

wish for friends on Mars.I’ve no notion

what Martians do on their small orb

(neririing or kiruruing or hararaing).But sometimes they like to have friends on Earth.

No doubt about that.Universal gravitation is the power of solitudes

pulling each other.Because the universe is distorted,

we all seek for one another.Because the universe goes on expanding,

we are all uneasy.With the chill of two billion light-years of solitude,

I suddenly sneezed.

Full of the vibrancy of youth, this poem sets the joys of human life in the embrace of the vast universe against the solitude, anxiety, and longing for friends that everyone feels. From the moment that they are born into this world until their death, people are burdened with a fundamental sadness. Living amid the continual passing of four bountiful seasons, in ancient Japan people were sensitive to the changes in life, expressing the loneliness of existence in the phrase mono no aware.

Knowing their own imperfections and distortions, people have a need for others. They pursue distant dreams seeking something they feel sure will make them whole. Encountering words with a quiet warmth within their cold exterior, they can only sigh, “What a pitiful thing is to live in this world.”

The poem is reminiscent of works by the twelfth-century poet Saigyō, who set aside a promising career as a warrior to become a monk and a writer of waka. Almost a millennium ago, like the young Tanikawa, he wrote poems of self-discovery about the night sky and the quiet of nature: Nageke tote / tsuki ya wa mono o / omowasuru / kakochigao naru / waga namida kana (“Lament!” it seems / the moon wants / to tell me— / But no, my tears / only seek to blame); Kokoro naki / mi ni mo aware wa / shirarekeri / shigi tatsu sawa no / aki no yūgure (Even one who’s / renounced feeling / knows pathos— / a snipe rising from a marsh / this autumn evening).

Tanikawa’s casual, plain-spoken poem appears modern at first glance, but it may have a direct connection with traditional Japanese sentiment.

A Flexible Mind

Born in Tokyo on December 15, 1931, Tanikawa Shuntarō was the only child of the philosopher Tanikawa Tetsuzō and his wife Takiko. At a time when militarism was on the rise, his parents, raised in the liberal atmosphere of Taishō Democracy, preserved an enlightened home environment. They spent every summer in a second home in northern Karuizawa, at the foot of Mount Asama. Nature and the image of the universe that appears in his later works was strongly influenced by his feelings in this location. He was 13 years old and still at school when World War II came to an end in 1945.

How old someone was when the war ended becomes a major point when discussing postwar literary figures. In this total war, in which 3 million people died in Japan alone, were they civilians on the home front, soldiers, or still just children? A slight difference in age led to very different experiences, affecting writers’ literary sensibilities. Among Japan’s most prominent postwar poets, there were people like Ono Tōzaburō, who was involved in the wartime anarchist movement, sympathetic with proletarian poetry, and opposed to traditional lyricism. Others included Ayukawa Nobuo and Tamura Ryūichi, who were drafted into the military, and wrote a new kind of “hard” (kōshitsu), modernist poetry in the literary coterie magazine Arechi (Waste Land).

Meanwhile, Tanikawa was still a boy when the war ended, and while he had unpleasant experiences, like seeing corpses in burned-out ruins, he retained a flexible mind. When he was 21, he started contributing to the coterie magazine Kai (Oars). Other writers for the magazine included Kawasaki Hiroshi, Ibaragi Noriko, and calm, accessible poets like Ōoka Makoto, who was of Tanikawa’s generation.

Tanikawa Shuntarō in May 1980. (© Jiji)

A Distrust of Words and Poetry

From the 1960s onward, in Japan’s increasingly wealthy society, Tanikawa took on a range of work with words, and became better known. In 1962, he won the Lyrics Award at the Japan Record Awards for “Song for Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday,” playing word games with the names of the days of the week. The following year, he wrote the words for the theme song of the hit anime Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy), based on the manga by Tezuka Osamu

In a section from his Toba sequence in 1965, he shocked the literary world by questioning what it meant to be a poet—the English translation here is by Takako Lento.

I have nothing to write about

My flesh is bared to the sun

My wife is beautiful

My children are healthyLet me tell you the truth

I am not a poet

I just pretend to be one

The book Shijin nante yobarete (Though They Call Me a Poet), including interviews of Tanikawa Shuntarō by Ozaki Mariko. (Courtesy Shinchō Bunko)

Can poetic words grasp directly the things that exist in the world and the emotions that rise up inside people? In an interview with Ozaki Mariko, a former member of the Yomiuri Shimbun editorial committee, Tanikawa said, “I feel like I began with a kind of resignation over the extent to which words are possible or effective.”

In other interviews too, he talks about how his distrust of words and poetry drove him to search for many forms of expression.

From the 1970s, Tanikawa pursued the potential of words, undertaking new creative challenges that previous poets had not tried.

Through his Word Play Poems, published as a picture book in 1973, he aimed to make poetry more accessible by writing it in the basic hiragana script, and reached new readers. Since the late nineteenth century, Western concepts had been imported into the Japanese language using kanji characters, which could make them hard to grasp. Through his poems for children, Tanikawa made the language softer and more supple. In 1975, he won the Japan Translation Cultural Award for his rendering of Mother Goose rhymes into Japanese that hardly used kanji at all. He also translated Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts comic strip.

Despite his rich poetic activities and other writing, in his private life Tanikawa may have been forever looking for a spiritual connection with someone real, and poetic sentiment that transcended words. Beginning with his marriage at 22 to the poet Kishida Eriko, he married and divorced three times. His third wife, Sano Yōko, whom he married in 1990, was a writer and illustrator of children’s books, best known for the perennially popular The Cat That Lived a Million Times. Although his love affair with this talented woman brightened up his middle years, Tanikawa told Ozaki Mariko that “I had a never-ending series of fresh wounds.”

Looking back on modern literary history, the poet Nakahara Chūya and the critic Kobayashi Hideo were involved in a love triangle over the actress Hasegawa Yasuko. Takamura Kōtarō wrote wonderful poetry about his wife Chieko, but his overwhelming passion and intense talent drove her mad. Poets who endeavor to stay faithful to both their hearts and words are fated to struggle in love. Tanikawa was no different.

Bringing Comfort

Tanikawa’s poems have always been a familiar, nearby presence for Japanese people. His 1982 poem “Morning Relay,” which prompts reflection on the vast size of the planet, appeared first in textbooks and then in 2003 in a Nescafé commercial. After the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, Tanikawa’s 1971 poem “To Live” was widely shared online, bringing comfort to many.

His words have touched the hearts of people from other countries too. Written in simple language with superlative rhythm, the poems are appealing to learners of Japanese.

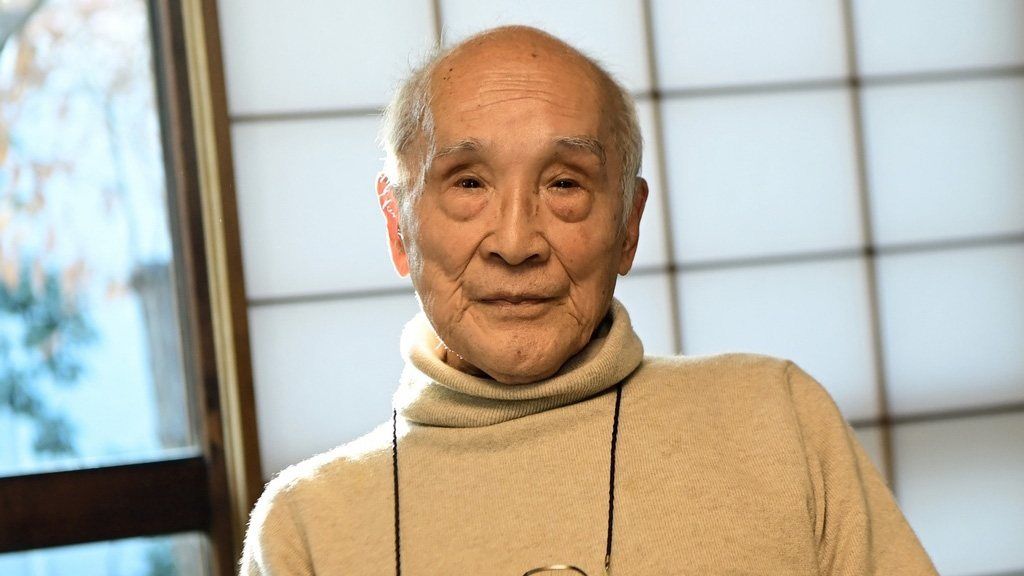

Tanikawa Shuntarō in his writing room in Tokyo in 2020. (© Kyōdō)

The Chinese poet Tian Yuan was born in 1965 and grew up through the Cultural Revolution. He encountered Tanikawa’s poetry after studying in Japan, and was deeply moved, going on to translate it into Chinese. It also inspired him to write his own poems.

What Tian took from Tanikawa was not only the richness of his language, but also his ability to shed the hard armor of politics and social systems and turn his attention to the sensations of life and nature. It is a style that cherishes the small pleasures of this world.

Tanikawa’s poetry has been translated into over 20 languages, including English, Chinese, French, and German, becoming a way to get to know Japanese culture for people around the world. He received a Japan Foundation Award in 2019. Appearing at the ceremony in a wheelchair, he drew applause from assembled reporters when he said: “I don’t want to become an authority.”

After having published more than 2,500 poems, and even into his nineties, Tanikawa was taking on new challenges. In a book published last year based on a format of correspondence with Brady Mikako, he wrote a poem describing a sense of nostalgia in wearing diapers again after 90 years. Even as his life became more restricted through the hardships of aging, he was able to evoke tender feelings through his poetry.

Tanikawa’s works will continue to shine like stars and comfort us in our loneliness.

Information on Cited Works

“Two Billion Years of Solitude,” the English translation by William I. Elliott and Kazuo Kawamura of “Nijū oku kōnen no kodoku” is taken from New Selected Poems. The excerpt from “Toba 1” comes from Takako Lento’s translation in The Art of Being Alone: Poems 1952–2009. Original Japanese titles for other Tanikawa works mentioned: “Getsu ka sui moku kin do nichi no uta” (“Song for Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday”); Kotoba asobi uta (Word Play Poems); “Asa no rirē” (“Morning Relay”); “Ikiru” (“To Live”). Sano Yōko’s 100 man kai ikita neko was translated as The Cat that Lived a Million Times by Judith Carol Huffman.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 24, 2024. Banner photo: Tanikawa Shuntarō at his home in Tokyo on December 24, 2021. © Kyōdō.)