Growing a New Future: A Fukushima Farming Village Strives to Survive

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Drastic Population Fall

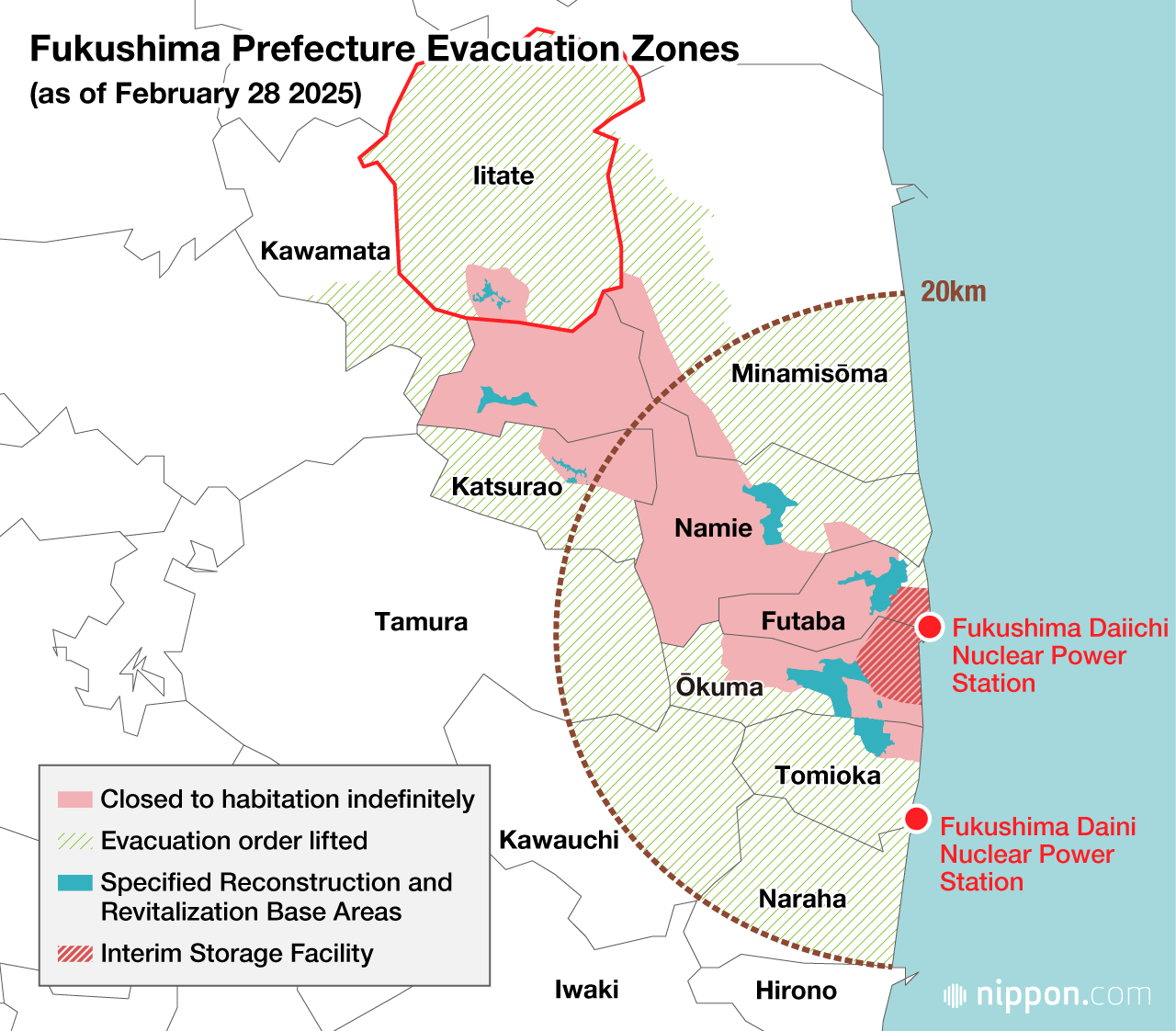

The village of Iitate is located in the hilly northeast of Fukushima Prefecture. It is 30–40 kilometers from the Tokyo Electric Power Company Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, the site of the terrible March 2011 nuclear accident.

Immediately after that accident, the government issued evacuation orders for people living within a 20-kilometer radius of the power station, and Iitate received an influx of evacuees from Futaba, Ōkuma, and other municipalities in the vicinity. Later, radioactive material from the reactor was carried northwest by the winds, and Iitate was found to have serious levels of radioactive contamination.

Despite its relative distance from the reactor, these conditions forced the evacuation of the entire town. The evacuation order came roughly a month after accident, and remained in place for nearly six years, until the end of March 2017.

Eight years have now passed since the lifting of evacuation orders, with the exception of some exclusion zones that remain in force, but the village has changed significantly during these years.

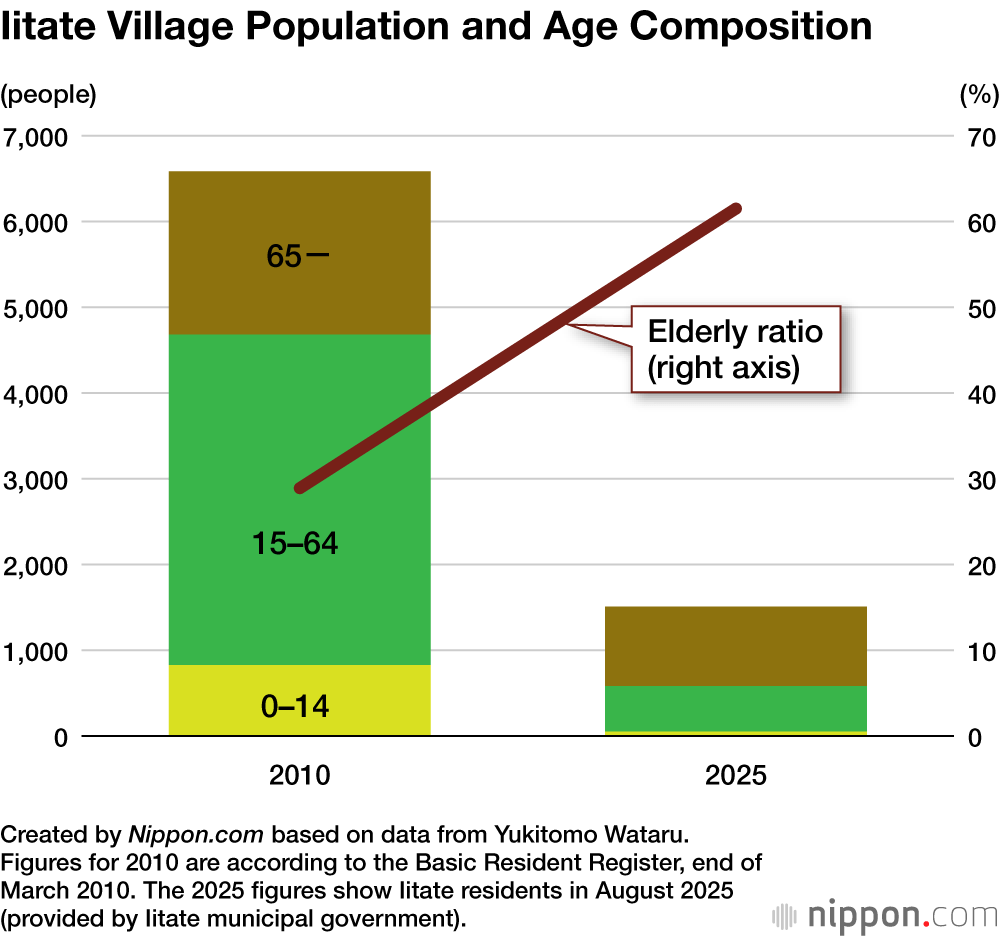

A year before the accident, as of the end of March 2010, Iitate had a population of 6,584 according to the Basic Resident Register. Officially, the population has now declined just over 30% to 4,400. In fact, though, this figure reflects the number of people who retain their official residency registration in the village; only 1,508 people are actually living there today, less than a quarter of the pre-accident level.

Some people retain their official residency in the vague hope they might move back one day, while others possibly do so in order to continue benefiting from evacuee support measures. People who evacuated from the 13 municipalities affected by the nuclear accident are entitled to medical, welfare, education, and other government services where they live without needing to update their residency.

But Iitate faces challenges other than just depopulation—the percentage of elderly people has also risen significantly. In 2010, some 28.9% of the residents were aged 65 or over, but that figure has now more than doubled to 61.5% (see graph). Returnees have predominately been elderly, while working-age former residents have not returned.

Working-age former residents who moved to urban areas have found employment, and their children have settled into their new communities, making it difficult to move back to a village whose infrastructure had collapsed. Understandably, they are reluctant to move back no matter how much they love Iitate, considering the inconvenience and limited educational options.

Looking to a New Crop as a Way Forward

The village meets the criteria of an endangered community—a genkai shūraku, literally a “settlement pushed to its limit”—and preserving the wellbeing of returned residents has become a key issue.

Most who came back have settled in their original homes, hoping to recommence their former occupation, such as farming. One such man, aged in his seventies, evacuated to temporary housing in the city of Date, Fukushima. He recalls the experience “I was surrounded by people I didn’t know. I was always anxious, sensing people’s eyes on me. I couldn’t even grill fish—I was too worried the smell would upset others. Life in our village is the best.” A woman who spent time living in prefab emergency shelter says, “What was tough was waking up each day with nothing to do.” For the villagers, farming is more than a means of livelihood—it provides them with fulfillment, and is part of their identity.

Agriculture is the foundation of the community. In the past, residents cooperated in rice planting and harvesting, a tradition that bound them together.

Replanted egoma seedlings. (© Yukitomo Wataru)

In April 2020, the farming households in Iitate’s Ōkubo-Yosouchi administrative district formed Yui Nōen, a farming cooperative, in an effort to preserve the community and its people’s sense of purpose. I joined a community revitalization group at the invitation of Nagashō Masuo (aged 78), head of the administrative district and representative of the cooperative, whom I met before moving to Iitate while surveying postdisaster reconstruction in the region.

Yui Nōen mostly grows egoma (oilseed perilla) on a roughly two-hectare property. Egoma is an annual crop related to the type of perilla popularly known as shiso. Seedlings are grown in May, then transplanted to the field in late June. It develops ears that produce dozens of white flowers in late summer. Although egoma is relatively easy to care for, the initial replanting, as well as the harvest and threshing in late October, are labor-intensive.

For threshing, blue plastic sheets are spread out in the field, and picked ears are beaten to drop the seeds. Debris is then removed by sieve. The seeds are taken indoors, washed, and dried, and impurities are removed by tweezers. Finally, the oil is extracted and bottled.

Nagashō (right) threshing harvested egoma. The ears are beaten against a plank and the seeds drop onto the plastic sheet. (© Yukitomo Wataru)

Yui Nōen limits its use of farming machinery and agrochemicals, and harvested seeds are processed manually. Although it would be possible to reduce labor requirements with machinery, the members here deliberately adopt techniques that involve more residents.

Nagashō explains: “Producing egoma isn’t strenuous, but it takes time and effort. We see that as a benefit.” The residents can chat and share old stories during work breaks. “My granddaughter is already a working adult,” says one worker. “Oh, she was still in elementary school when you evacuated,” comes the reply. Another remarks: “Y’know, this field used to be a rice paddy, but it got overgrown with weeds because there was no one left to tend it.”

Members of Yui Nōen chat while they take a break. (© Yukitomo Wataru)

For grass-cutting and other laborious tasks, 10–20 people gather, including some who still live away from Iitate, and they share updates and news about other friends as they toil. University students and other supporters join in the replanting and harvesting, which increases the relational population—namely, the nonresidents who maintain ties with the region.

Social Functions of Farming

Egoma is mostly used to produce an edible oil that is rich in ALA, EPA, and DHA, so-called Omega-3 unsaturated fatty acids, and has attracted attention as a health food in recent years. Heating the oil destroys key nutrients, so it is usually consumed uncooked in salad dressing, on tofu, or in miso soup, for example. It has long been used in Fukushima, where it is called jūnen (which sounds like the Japanese for “ten years”). Locals say the name originates from the belief that eating it can extend your life by a decade. Egoma oil from Yui Nōen is bottled for sale at rural roadside stations. The product name is written with characters presenting a play on words that roughly translates as “happy egoma: live ten years longer.”

It sells for ¥1,250 for 45-gram bottle and ¥2,500 for a 100-gram bottle. Egoma seeds are also sold, at ¥400 for a 100-gram bag. The seeds can be lightly toasted, ground like sesame and sprinkled on rice balls, or mixed into soy sauce and sugar to make relish for mochi rice cakes.

The products are also sold through Yui Nōen’s website. Recently, the group received a bulk order from a consumer cooperative based outside of the prefecture. Yui Nōen also aims to register its produce as a reward under the government’s furuzato nōzei “hometown tax” scheme.

Egoma products from Yui Nōen (left). The Yui Nōen stand at an event held in Yokohama in November 2023. (© Yukitomo Wataru)

Late last year, I took part in local patrols to raise fire and crime prevention awareness. A civilian firefighter who accompanied us mentioned that many elderly people have lost their spouses and live alone. At night, about half of the houses have no lights on. In many cases, they are not abandoned—the owners now live elsewhere, returning just for weeding and cleaning.

There are also many fields going untended, because the farmers are too old to operate agricultural heavy machinery. A development corporation funded by the farming cooperative and the village takes care of some fields to grow rice for stock feed, but it cannot manage all of the land.

In this regard, growing egoma, which is less of a burden on the elderly, is an effective option that can harness the benefits of farming for this endangered community. From the perspective of agricultural theory, it also offers several important elements that tend to be ignored in discussions of industrial theory—the promotion of incidental social functions of agriculture, such as supporting community and providing elderly individuals with a purpose in life, all of which lead to the “human recovery” needed in the wake of disaster.

Prior to the nuclear accident, Iitate promoted a concept it termed “madei life,” or “slow living.” The word madei is local dialect for “careful.” Doing things carefully rather than prioritizing cost and time efficiency is a form of “slow living” that values the harmony between the traditional lifestyle and nature.

The 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake raised similar issues—when major disaster strikes already depopulating regions, people are quick to suggest that elderly residents should abandon their “doomed community” and relocate to urban areas. While this may seem reasonable in administrative or economic terms, it is debatable whether it is actually better for the persons concerned.

Uncertainty clouds the long-term prospects of Yui Nōen’s activities, given the age breakdown of its membership. Efforts will be needed to boost profitability if the younger generation are to take the reins. But as this year’s harvest approaches, one thing is certain—the elderly residents who gather at Yui Nōen will for the time being continue to enjoy working actively and living in their community.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Members of Yui Nōen planting egoma seedlings in Iitate, Fukushima Prefecture. © Yukitomo Wataru.)