The Year of the Fire Horse: Why Did Births Plummet in Japan in 1966?

History Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Hot-Tempered Women?

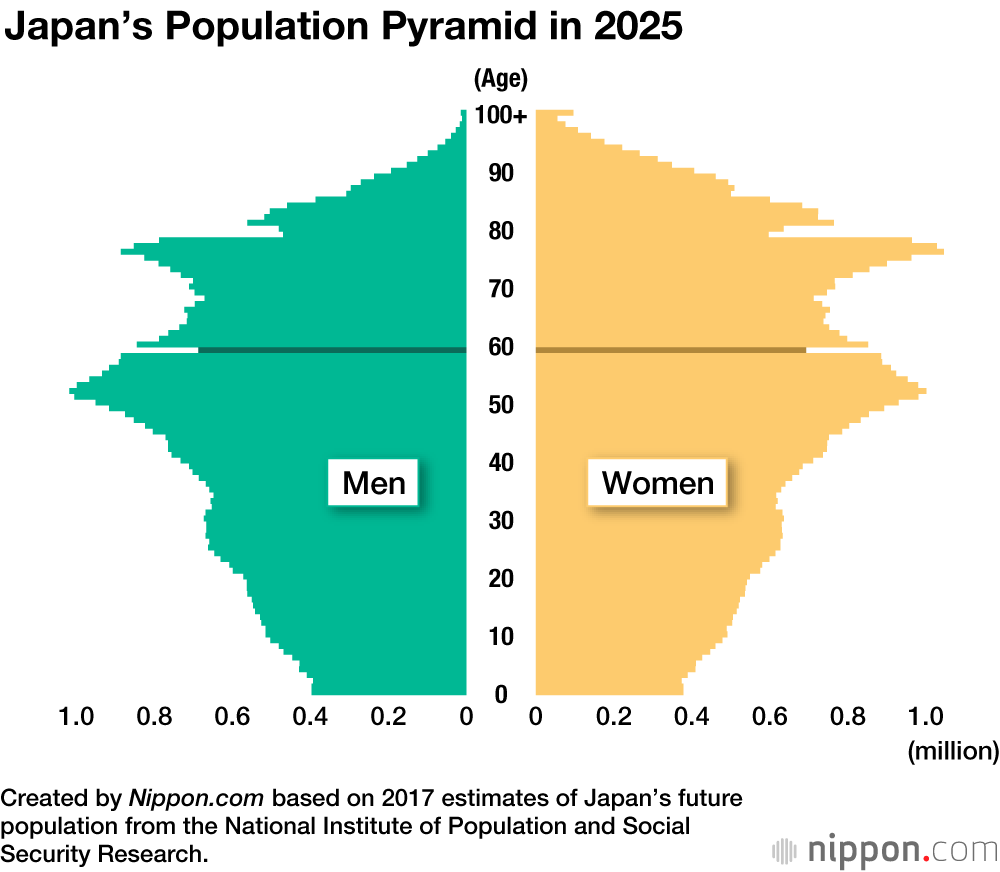

Japan’s population pyramid has a curious quirk. At the point where the 1966 births are recorded, there appear to be notches cut away on either side. In that year, there were 1,361,000 births, which was around 500,000 fewer than either the previous or following year. It may be difficult to believe, but this drop in the number of newborns is said to have been due to young couples’ fears over an old superstition.

The superstition is based on the 60-year cycle of 12 zodiacal animals associated with the five elements: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. In the early Edo period (1603–1868), a malicious story spread that women born in the Year of the Fire Horse were hot-tempered and would eat their husbands alive. This was the fake news of the day, spread via puppet theater and popular books, with no rational evidence to back it up.

The story of Yaoya Oshichi, who committed arson to try and meet the man she was infatuated with, was a favorite theme of ningyō jōruri puppet theater. Oshichi was born in the Year of the Fire Horse (1666). (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

The myth led to fewer marriage proposals for women who were born in the corresponding year. As the 60-year cycle came around again, concerns about girls’ future marriage prospects led to some couples avoiding pregnancies or recording girls’ births as having taken place either the year before or after. There were even cases of infanticide.

While the zodiacal cycle itself originated in ancient China, the irrational taboo affecting women’s marriages, pregnancies, and births is unique to Japan.

Why was it though that 1966 saw the biggest decline in births? In 1846, under the shogunate, or 1906, people paid far more attention to what the calendar considered to be lucky or unlucky than in the postwar period, but the demographic statistics do not show any noticeable dip in births at those times.

Checking the Facts

In 1966, Japan was in the middle of its high-growth period, and had already become a modern, industrialized nation not greatly different from how it is today. Why was it—in an era when television broadcasts had begun and expressways and bullet trains were starting to connect the country more closely—that an old superstition apparently reached its peak of power? How did people learn about it and react, and how did young couples avoid having children that year? And did this folk belief continue to weigh on girls born in 1966?

The Fire Horse phenomenon has long been seen as something supernatural or else an inexplicable mystery. For this reason, what actually happened has not been sufficiently investigated.

When I looked at the records, I discovered a number of little-known facts. One is that the gender ratio of newborns in 1966 shows almost none of the imbalance of previous Years of the Fire Horse. There is no sign that any girls born in this year were killed, as had happened in the past. Also, even though abortion was legal, there is no evidence that the number of abortions increased in 1966.

At this time, mothers received a maternal and child health handbook several months before birth, which generally took place in a hospital, so it was not possible to record the birth as taking place either earlier or later than it actually did. By process of elimination, the low number of births in 1966 must have been due to many young married couples consciously deciding to avoid pregnancy.

A Media Boom

Looking back, it is apparent that there was a huge amount of media coverage from 1964 about the Year of the Fire Horse in newspapers and magazines, as well as on television shows. Alongside warnings to be careful and avoid pregnancy, there were admonishments to ignore it and to stamp out superstitious belief. As a result, everyone in Japan knew the purportedly inauspicious Fire Horse was coming, whether they were likely to have a new child in the family or not.

Among the coverage, there was a strong focus on the tragedies encountered by women born in 1906, the last time the cycle came around. As they approached the age of 20 around 1925, they found it difficult to get married, and a number of unmarried women committed suicide. These stories had a powerful impression on readers.

In earlier occurrences of the Fire Horse, the average life expectancy was somewhere in the forties, so few experienced the full 60-year cycle. However, with the rapid lengthening of lifespans, there were many people born in 1906 who were still alive in 1966. It is said that older relatives warned of the calamities that a girl would face if born in the fateful year, encouraging young couples to avoid getting pregnant. This kind of harassment is unimaginable today, but it had a significant influence at the time. The flood of media information combined with shared individual memories of the previous occurrence.

All About Timing

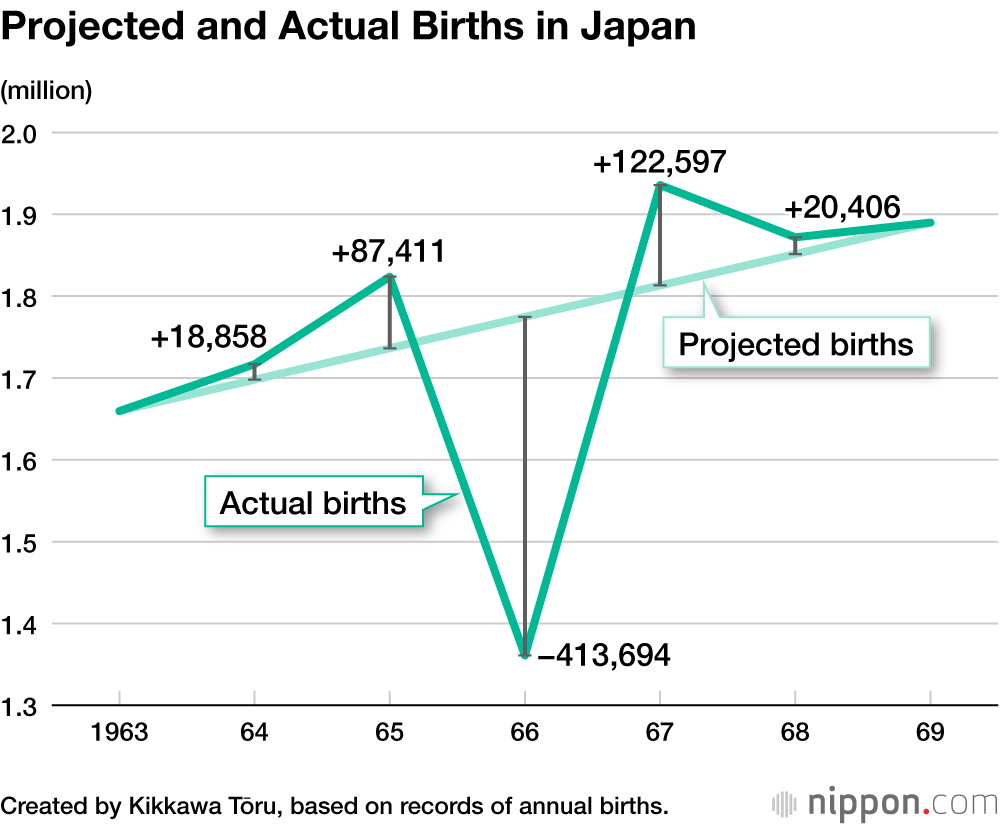

These background elements played their part, but there is a surprising decisive element that sparked the birth drop phenomenon. While the number of births in 1966 was around 414,000 lower than expected, there were 87,000 births more than expected in 1965 and 123,000 more in 1967—the extra births in these years add up to 210,000 overall. This suggests that married couples took into account the coming of the Fire Horse year and consciously shifted their timing for giving birth. The three years of rise, fall, and rise again can be seen to fit together as a set, shaped by efforts to control pregnancies.

A closer look at the data shows that 1966 had the highest proportion of first children among overall births since records first began. This suggests that birth control measures were taken among people who were already parents. There seem to have been over 200,000 cases around the time of the Fire Horse year where married couples with one child or more used contraception to adjust the timing of further pregnancies.

Behind the quiet unfolding of this major shift was an extensive campaign of social education encouraging young mothers not to have large numbers of children by spacing out births with two or three years in between. This had taken place nationwide since the 1950s through advice on birth control provided by midwives.

A conference in April 1954 celebrates the foundation of the Japan Family Planning Association. (© Kyōdō)

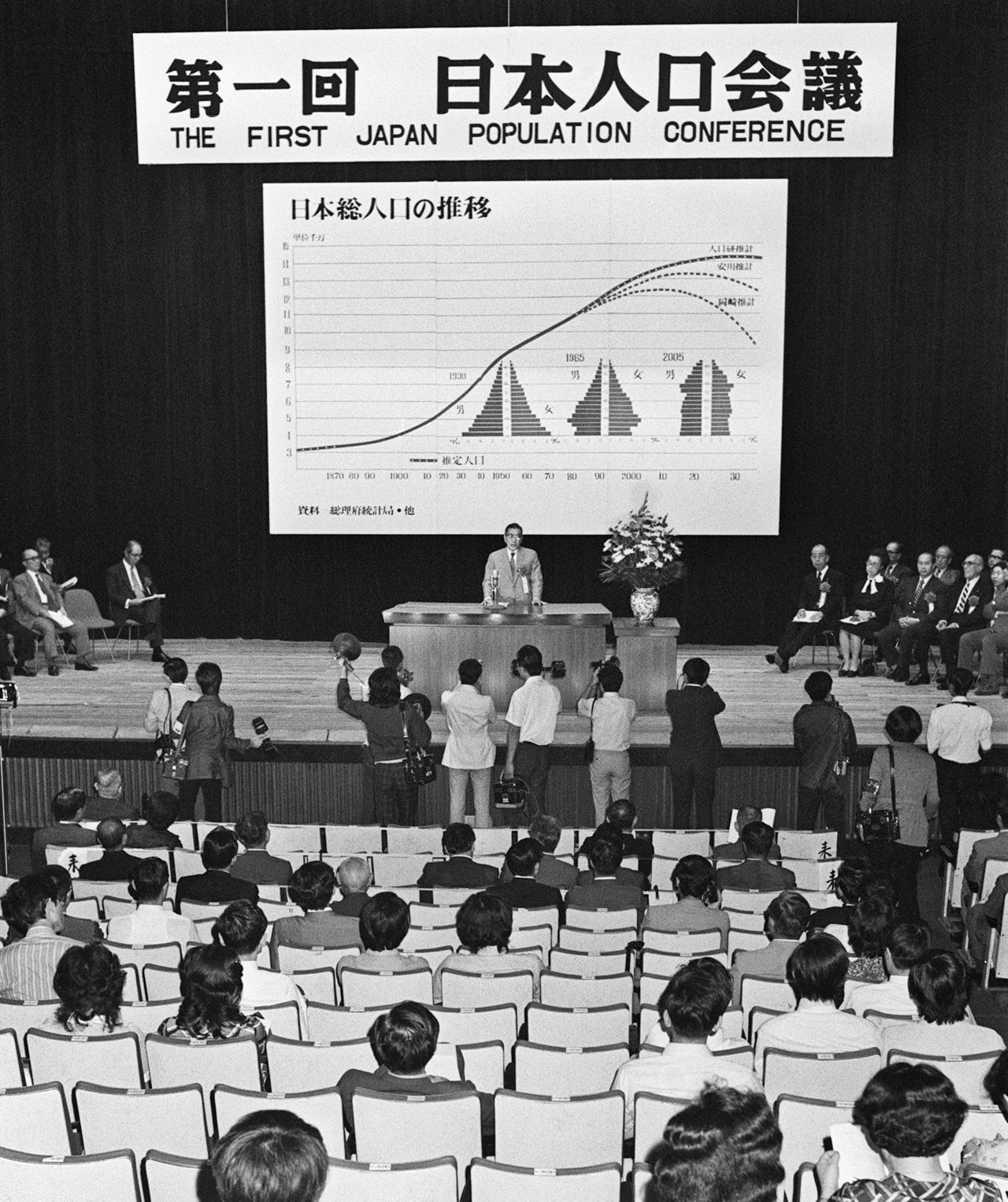

The first Japan Population Conference in 1974 adopted a declaration stating that effective measures are needed to keep population increase under control. Photograph taken on July 2, 1974. (© Jiji)

The plunge in the number of newborns in 1966 was not a tragedy where people gave up on getting pregnant or had abortions due to superstitious terror or reluctant acquiescence to peer pressure. Instead, the Fire Horse phenomenon acted as a nudge or excuse for married women to actively pursue planned timing of births through contraception, as was being encouraged at the time, over the course of three years.

The Fire Horse belief is an old superstition, but the drop in births came about due to a public boom in interest, fueled by the mass media, in combination with a generation of women of childbearing age making rational decisions protecting their reproductive health and rights, based on scientific knowledge.

This miraculous blending of tradition and modernity could only have taken place when it did.

What Will Happen in 2026?

In 2026, it will be the Year of the Fire Horse once again. With Japan’s births in steady decline, online discourse shows concern about people’s susceptibility to fake news, and the possibility of a large drop in the number of newborns.

A phenomenon based on superstition rooted in the patriarchal thinking of a century and more ago will surely not take place. And even if one might consider whether something like 1966 could happen again, young married couples in Japan are already routinely using contraception to prevent the unexpected birth of a child and accompanying changes to their lifestyle. In other words, not having babies is now the default state, which is a great difference from 60 years ago, when birth control was being encouraged. In which case, even if the 2026 Fire Horse were to encourage planned childbirth, it would not have much effect. In today’s Japan, with its serious birthrate crisis, a further significant reduction is impossible.

(Originally published in Japanese on October 2, 2025. Banner photo: A mother with her baby in the 1960s. © Kyōdō.)