Colonel Sanders Gets Ready for the Year of the Horse

Society Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

For obvious reasons, Christmas is not a public holiday in Japan—here at Nippon.com we spent December 25 in the office beavering away as usual. But it’s not quite an ordinary day either. For most of the past two months, we’ve been treated (subjected?) to decorated trees and glittering lights and “White Christmas” and all the rest of it, with Colonel Sanders resplendently clad in Santa Claus red outside the nation’s innumerable KFC outlets. KFC announced today that it sold some ¥6.61 billion of chicken over the December 21–25 period—a new record for Japan, where the jovial Colonel has become an essential part of the Christmas season in many people's minds. As the season approaches its climax, he is joined in the seasonal cosplay game by nation’s convenience store workers, who do their bit to add to the yo-ho-ho by togging up in rather fetching Santa-and-Rudolph outfits.

But Christmas Day itself tends to pass without notice. The real action takes place the night before—December 24 is universally acknowledged as the most romantic night in the Japanese calendar. Commonly referred to simply as “Eve,” this is the one night of the year when no self-respecting woman wants to end up without a date—a humiliation that inspired many a weepy J-pop hit.

On my way home on Tuesday night, the streets of Ginza were abuzz with lovey-dovey couples, many of them sporting his-and-hers surgical masks to protect them from the devilish winter germs. Remarkably for Japan, there was even one amorous couple smooching enthusiastically on a street corner. The boutiques and department stores of the nation’s most fashionable shopping district were full of salarymen hunting desperately for the perfect romantic gift, many of them looking slightly dazed and confused.

But of course, the real big deal in Japan is the New Year. Over the past day or two, the first kadomatsu (“gateway-pines”) have begun to appear in front of buildings ready for next week, when most businesses will close down for the holidays. Ancient Shinto belief holds that the spirits of the kami gods dwell in living trees. It is considered bad luck to put out the trees on New Year’s Eve, and most companies and families put them out way in advance of that. They are often placed in pairs, one on either side of the entrance, like the impressive specimens below that appeared in front of our offices in the Nippon Press Center Building yesterday afternoon.

Kadomatsu decorations in Kasumigaseki and Asakusa, Tokyo.

Kadomatsu decorations in Kasumigaseki and Asakusa, Tokyo.

View Colonel Saunders Gets Ready for the Year of the Horse in a larger map

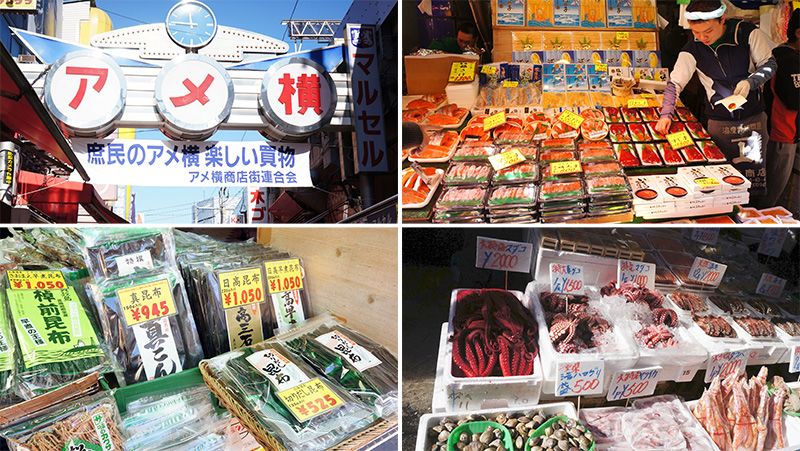

Ame-yoko, a refreshingly grungy shopping street a short hop away from Ueno Park, is one of several places that sees peak business at this time of year. It often features on TV news reports as a reliably recognizable symbol of the year-end rush. The crowds were already out in force yesterday morning, snapping up shrimp, crab, konbu, kazunoko and other goodies for the osechi-ryōri traditionally eaten at New Year. Dating from the days before refrigeration, osechi is made in advance and keeps over the holiday period when shops are closed for business. Ueno and the arcades around it are a world away from Ginza and its almost robotically choreographed bows and “irasshaimase” choruses. Here things are much more down to earth—a place where people speak in gruff and friendly tones unadorned with honorifics or fancy phrases.

Ame-yoko in Ueno, a popular spot for year-end shopping.

Ame-yoko in Ueno, a popular spot for year-end shopping.

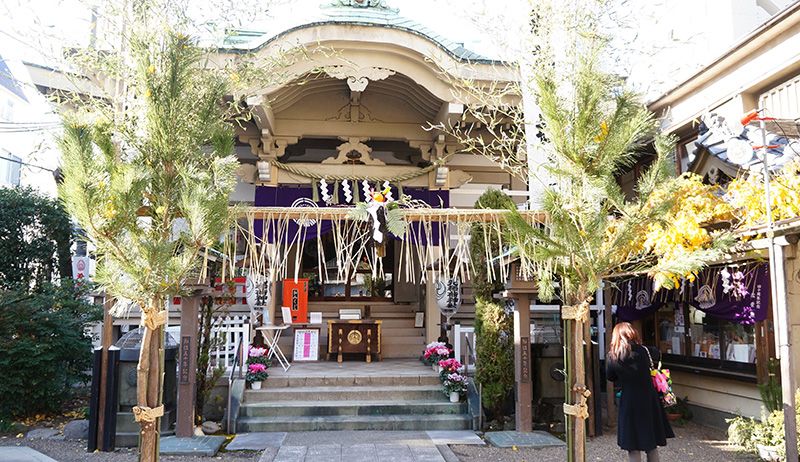

A short subway ride from Ame-yoko is the Yasaki Inari Shrine, where the New Year decorations were already out yesterday afternoon. The shimenawa combination of sacred rope and paper is a Shinto symbol of the presence of the kami and a reminder of the invisible world of the gods. At New Year, many people hang a shimenawa at the entrance to their home. This is believed to prevent bad luck from entering the house. They are also hung inside the house in places where people use water or fire to protect against mishaps in the coming year: another place you often see them is on the front of people’s cars.

The Yasaki Inari shrine, dressed up to receive the New Year crowds.

The Yasaki Inari shrine, dressed up to receive the New Year crowds.

The famous Sensōji temple in Asakusa throngs with crowds on every day of the year. In late December, the throng becomes a crush. Huge banners over the Nakamise shopping street that leads to the temple mark the season with illustrations showing traditional New Year decorations and games: traditional pastimes like tako kites, karuta playing cards (used in a game in which family members compete to match lines from famous old poems), hagoita (decorative wooden paddles traditionally used to play a kind of battledore game) and koma (spinning tops).

Decorations featuring New Year pastimes at Sensōji temple in Asakusa.

Decorations featuring New Year pastimes at Sensōji temple in Asakusa.

There are also all kinds of auspicious New Year’s symbols to bring health and good fortune in the coming year—the most prominent of which is the kagami mochi, a pair of rice cakes made from pounded sticky rice and topped with a daidai orange. The mochi cakes are thought to resemble the mirrors used in Shinto rituals as a symbol of the kami. The daidai is auspicious too, since it is homophonous with a word meaning “many generations.” It is traditional to display the kagami mochi on the family’s Shinto altar or elsewhere in the home until January 11, when the rice cakes are eaten in a ceremony called kagami-biraki (opening the mirror).

Kagami mochi for sale outside a local supermarket, Ueno.

Kagami mochi for sale outside a local supermarket, Ueno.

Come New Year’s Eve, these places, like most of Japan’s thousands of temples and shrines, heave with crowds that make Tokyo rush-hour look like a stroll in the park. At midnight, temple bells ring out to welcome in the New Year. Over the first few days of January, millions of people visit their local Shinto shrine to pray for peace in the coming year. Perhaps that’s what Prime Minister Abe thought he was doing this morning, when he made the first visit by a prime minister in seven years to the world’s most controversial war shrine.

One of countless horse-themed trinkets on sale at Nakamise, Asakusa.

One of countless horse-themed trinkets on sale at Nakamise, Asakusa.

A very Happy Year of the Horse to all our readers!