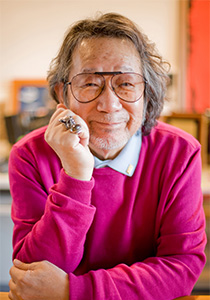

Filmmaker Ōbayashi Nobuhiko: War and Peace and Cinema

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Child of a Militaristic Nation

“I must be a very rare case among the world’s directors in that I made my first film as a child before ever seeing one.” Ōbayashi Nobuhiko, director of the cult horror comedy House, explains that he played with an eight-millimeter camera belonging to his doctor father when he was just three years old. This was in 1941, as Japan moved toward its fateful attack on Pearl Harbor. Ōbayashi was seven when the war finished in defeat. As he talks, he continually returns to discussion of this time.

“At seven, you’re still a child, but for that reason you’re able to calmly observe the adult world. I understood perfectly the grotesque and meaningless nature of war. I’d attended the schools of a militaristic nation for two years, learning that I should fight and die splendidly for my country, but I wasn’t part of the prewar or wartime generation. At the same time, I wasn’t quite in the postwar generation either. Because of this, the Japanese adults who abruptly switched to talking of peace when the war was over were the ones I trusted the least. While I respected directors like Ozu Yasujirō, Kurosawa Akira, and Kinoshita Keisuke, I thought of the 35-millimeter film cameras they used as tools of the aggressors. So I wanted to establish myself as a filmmaker with the 8-millimeter camera, which I identified as being on the side of victims.”

Shooting Hanagatami. (© Ōbayashi Chigumi / PSC)

Shooting Hanagatami. (© Ōbayashi Chigumi / PSC)

Staying Clear of “Systems”

In 1956, Ōbayashi began studying film at a Tokyo university. Although he dropped out in 1960, he continued to make 8-millimeter films, showing them in art galleries and other venues, as one of Japan’s first independent filmmakers. He won the special jury prize at Exprmntl 3, a 1963 Belgian experimental film festival, for his 16-millimeter work Tabeta hito (An Eater). His theatrical debut came with House in 1977. In the four decades since, he has made over 40 full-length films.

Before stepping up to the cinematic release of House, he made many of his own experimental films. At the same time, he was active in the television commercial production industry that thrived along with Japan’s rapid economic growth. He is said to have produced more than 2,000 commercials in a decade from the late 1960s to the late 1970s. The most famous ads featured international film stars like Charles Bronson, Sophia Loren, and Catherine Deneuve.

“You could say that I was a commercial director, but I never introduced myself like that. For me, ads were just short films. I never thought about films divided into different genres. It’s just the film business that has this system of putting fiction in one box and documentaries in another. Systems were what we hated most. They led to the war. Peace is dependent on how free people strive to be from systems. So I always think as hard as I can about how to keep a distance from them when I’m shooting a movie.”

Dragging Peace into Existence

Even when talking about films, Ōbayashi immediately starts discussing war and peace. For him the topics seem to be inseparable.

“The Japanese word happī endo [happy ending] comes from films. Cinema grew up in the era of two world wars and became a means of escaping from that strife. For the Jews who made their names in the film industry after being persecuted around the world, Hollywood was a new land that they’d traveled to seeking freedom.

“Of course, the unfortunate reality is that there will never be peace. But to admit this would mean that humanity has no hopes or dreams. So even if it’s a lie, depicting peace in film may create a truth from that falsehood. Undoubtedly, people in their hearts yearn for peace, and so the action of showing it on screen can one day drag it into existence. People in countries defeated in war longed for a cinematic happy ending. That’s why I think films were made all over the world.”

A scene from Hanagatami. (© 2017 Karatsu Film Project / PSC)

A scene from Hanagatami. (© 2017 Karatsu Film Project / PSC)

As a young boy, Ōbayashi felt a sense of betrayal at Japan’s defeat. Later, he was vehemently opposed to those postwar Japanese who did their best to act as if the war never happened. This is why the shadow of war is always present in his films, no matter how much they aim to entertain audiences.

Terminal Cancer’s New Perspective

Ōbayashi’s latest film, Hanagatami, is based on a short story written by Dan Kazuo and published in 1936, the year before the outbreak of war with China. The director first wrote a script for the piece in 1975, before the release of House.

“Both Hanagatami and House are about the same thing. Back in the days when I wrote them, nobody would watch a film based on a literary source, but they’d watch a horror flick. So I decided to make a film expressing my disgust for war—but I made it so people wanted to see it.”

Although he is pleased he was able to ultimately make Hanagatami, he offers a warning. “After more than 40 years, this film has finally come into being. I feel happy, but at the same time I’m afraid we’re in a similar period. War was approaching when the story was written, so Dan probably wasn’t able to write what he really wanted to. I imagined what he wanted to write and added it to my interpretation. If you said then that young people were considered as nothing more than cannon fodder, you’d get taken out and shot. He couldn’t express that, so he turned it into a story of young people’s love and friendship.”

Ōbayashi Nobuhiko directing actress Tokiwa Takako on the set of Hanagatami. Mitsushima Shinnosuke is seated at the right. (© Ōbayashi Chigumi / PSC)

Ōbayashi Nobuhiko directing actress Tokiwa Takako on the set of Hanagatami. Mitsushima Shinnosuke is seated at the right. (© Ōbayashi Chigumi / PSC)

In August 2016, two hours before a staff meeting the day before the start of filming, Ōbayashi was told he had stage-four lung cancer and six months to live. Then, two days after filming began, a further hospital visit halved this to only three months. Yet, unexpectedly, the director remembers feeling happy.

“While I was waiting forty years for the time to be ripe for this film, I was also waiting for myself to be ready. Mishima Yukio wrote of Hanagatami that the state had power of life and death over the young characters living in wartime. The only freedom they had was to put their all into loving someone and rebelling against the moral code. I worried whether we, who have enjoyed all the pleasures of the peaceful postwar era, had the right to make films about the youth of our parents’ generation.

“When I met Dan Kazuo forty years ago and got his permission to adapt the story, he had terminal lung cancer. Knowing I was in the same position, I felt happy that I could finally have the same experience of regret and resignation as that generation. I had to say now the words that they couldn’t say. At the same time, this means passing the message on to young people—born in a peaceful age—who will live on into the future.”

The End of the Corridor

Ōbayashi says he recently remembered a haiku by Watanabe Hakusen (1913–69), who evaded the eyes of wartime authorities while continuing his poetic activities.

戦争が廊下の奥に立つてゐたSensō ga / rōka no oku ni / tatteitaWar was

standing at the

end of the corridor

“Young people today have this sense that conflict is coming. Ask them and they will clearly say, ‘We are the children before the war.’ I might say that the film Hanagatami connects the forgotten postwar and the era of the coming war. Talking about past wars acts to create future peace. As we’re the last generation to remember the war, we have a duty to convey what it was like.”

Apparently the film has struck a chord with young viewers. “It seems to have an urgency for them, so they can’t think of it as being someone else’s business. Today’s world is increasingly convenient, comfortable, and efficient. But I’d say that half the time these changes have made humanity unhappy rather than happy. Things that make life more convenient are also easily used for bad purposes.

“In an advanced information age, people no longer take responsibility for information. Knowing or not knowing is all that’s important. People tend to value both essential and irrelevant information equally, and a result is that all kinds of information seem like they have nothing to do with the person receiving them. But when we present information as someone’s experience within a film, it gains the power to make people think. I make films to convey experiences that can’t be understood through information alone, putting viewers within a story and making them feel for themselves the horrors of war.”

On to the Next Project

Hanagatami is an excellent film. Ōbayashi’s innovative direction applies abundant digital effects in what is a kind of compilation of the director’s themes. Viewers feel the power of the characters’ desperate fight in the energy that pours from the screen. But the director does not consider his job done. He is coolly considering his next project.

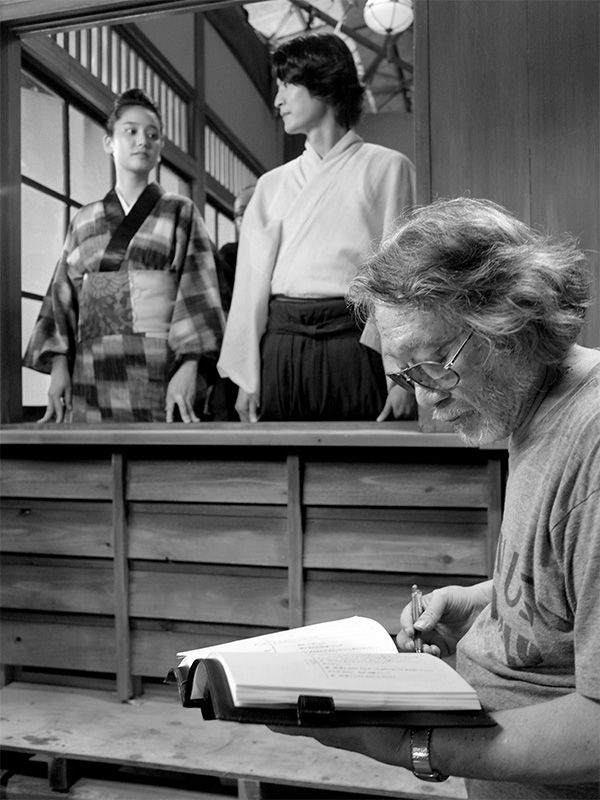

Ōbayashi Nobuhiko with script in hand on the set of Hanagatami. In the background are Yamazaki Hirona (left) and Kubozuka Shunsuke. (© Ōbayashi Chigumi / PSC)

Ōbayashi Nobuhiko with script in hand on the set of Hanagatami. In the background are Yamazaki Hirona (left) and Kubozuka Shunsuke. (© Ōbayashi Chigumi / PSC)

“I’ve lived as long as I have thanks to chemotherapy, which has extended my existence beyond my own ability to survive. With today’s medicine, it’s hard to die even of something like cancer. It depends how effective the medicine is, but they say it works better with optimists and people who live happily without worrying. It’s the same power of ’truth from falsehood‘ that you get with film.

“The possibility of a ’happy ending‘ has given me the courage to live. Even after I received my diagnosis, when I went to the film set, I felt well again. And I’ve lived on for seventeen months since then so I could finish making the movie. Now I think I’m ready to come to grips with the atomic bomb—that question with still no global solution that the film directors who came before me were unable to tackle.”

(Originally published in Japanese on January 29, 2018. Based on a December 18, 2017, interview at the studios of Niconico Live. With thanks to Dwango for cooperation. Photographs courtesy Ōbayashi Nobuhiko’s agency PSC. Reporting and text by Matsumoto Takuya of Nippon.com.)

Hanagatami

Released in Japan in December 2017. View the Japanese-language trailer below.

(© 2017 Karatsu Film Project / PSC)