What’s Next on the Ghibli Storyboard?

What’s Up at Studio Ghibli? Catching Up with Producer Suzuki Toshio

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Almost three years have passed since legendary animator-director Miyazaki Hayao, known for such global hits as Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Princess Mononoke (1997), and Spirited Away (2001), announced that The Wind Rises (2013) would be his last feature film. With Miyazaki abandoning commercial filmmaking at the age of 72, and animated film director Takahata Isao approaching 80, it was clearly a big turning point for Studio Ghibli, the animation studio inextricably associated with Miyazaki, Takahata, and producer Suzuki Toshio. In August 2014, the studio announced that it was shutting down its production department after the release of the 2014 When Marnie Was There (directed by Yonebayashi Hiromasa).

Since then, news has emerged that Miyazaki is working on a short film called Kemushi no Boro (Boro the Caterpillar), his first venture into computer-generated imagery. The studio is also breaking new ground with an international coproduction called The Red Turtle, set for release in Japan in September this year. The dialogue-free animation was awarded the Special Jury Prize in the Un Certain Regard section of the Cannes Film Festival in May.

So, what’s going on at Studio Ghibli these days, and what does the future hold? We could think of no one better qualified to answer those questions than producer Suzuki Toshio, Ghibli’s co-founder and chairman. For over three decades, Suzuki played a pivotal role in bringing the work of Miyazaki and Takahata to the screen, collaborating and not infrequently clashing with these two visionary directors. We found Suzuki at his office at Studio Ghibli in Koganei, Tokyo.

Making the Transition

Nowadays, Suzuki divides his time between the studio in Koganei and his private office in the Ebisu district of central Tokyo. “I feel like I had more time to myself back in the days when I was actually working on films,” he laments.

So, why did he decide to suspend production?

“There were a number of reasons. One was Miyazaki’s retirement from feature films. Also, Takahata was nearing his eighties. Of course, we could have kept going on autopilot with the younger directors we were grooming, but I felt we needed some time off to take stock, and I personally wanted more time to pursue my own studies.”

Time turned out to be a scarce commodity, however. People of all walks came calling on the assumption that Suzuki was unoccupied. He now spends more time at his office in the Ebisu neighborhood of Tokyo, close to where he lives, ostensibly because it is a good place for holding meetings. But the real reason, he confides, is that he prefers not to commute to Studio Ghibli every day.

“At Ghibli, I run into Miya-san [Miyazaki] and end up spending two or three hours in conversation with him. Plus, the commute to Koganei is an hour each way. That’s four precious hours taken out of my day. At that rate, there’s no way I can finish what I need to do. That’s the main reason [I don’t go to Ghibli every day],” he says with a smile, adding that the director is “a bit less talkative” now that he has his new computer-animated short film to keep him busy.

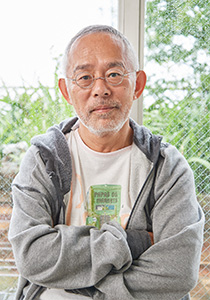

Suzuki at his Studio Ghibli office in Koganei, Tokyo.

Suzuki at his Studio Ghibli office in Koganei, Tokyo.

The irreverent tone with which Suzuki jokes about “Miya-san” and his latest endeavor somehow speaks to the strength of their personal and professional relationship. In fact, Suzuki was the one who suggested that Miyazaki try his hand at a CGI film.

“I thought it would be a good change of pace,” he says. “It could just as well have been hand-drawn, but I thought the challenge of a new technique might get him fired up again.”

A Pet Project, Resurrected in CGI

According to Suzuki, Kemushi no Boro was a piece of unfinished business for Miyazaki. He proposed the project around the same time that the Princess Mononoke concept came up for consideration.

“Miyazaki told me he wanted to do Kemushi no Boro, but I was against it,” says Suzuki. “I thought it would be difficult to make an 80–100-minute feature film out of a story with no human beings. Besides, I thought, ‘Boro is as a project he can undertake when he’s older, but the time to make an action film like Princess Mononoke is now.’ So, I suggested Princess Mononoke instead. It was a practical judgment call on my part.”

Boro came out of the mothballs after Miyazaki went into “retirement.” Suzuki knew that Miyazaki was itching to get back to animation even though he had given up making feature films. Seeing him at loose ends (“with nothing better to do than draw me into his random discussions”), Suzuki asked him if he would be interested in making a short film. He even suggested Kemushi no Boro as the subject.

“That made him mad,” says Suzuki. “He said, ‘I was just thinking about that myself, and you had to come out and say it first!’ Sure, I get it. We’ve known each other a long time.”

Suzuki offered Miyazaki two options for tackling his first-ever CGI-based anime: work with a group of animators at Pixar under John Lasseter, a friend of long standing, or hire a team of young Japanese CGI animators. “Miyazaki said, ‘I’d rather have a Japanese CGI team—because the folks at Pixar would be speaking English.’”

The first showing of Kemushi no Boro, to be screened exclusively at the Ghibli Museum, Mitaka, is probably a year or two off.

Ties that Bind

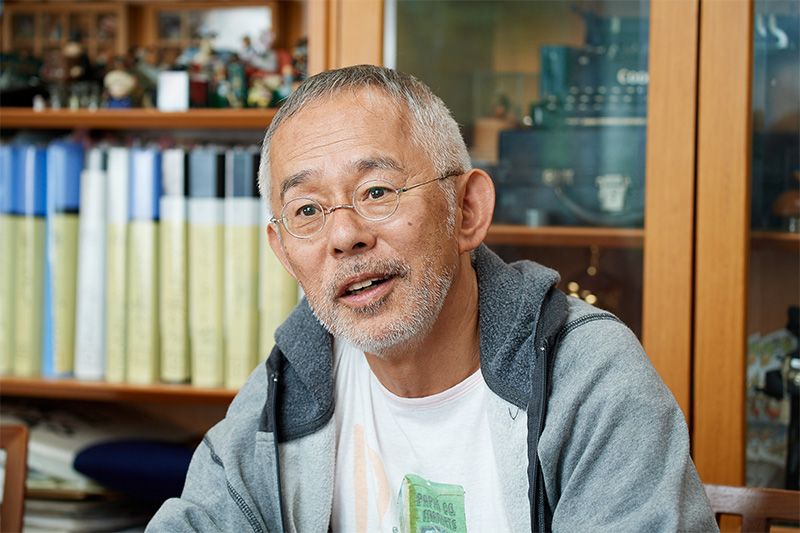

Memorabilia from past hits are among the trinkets adorning the shelves of Suzuki’s Studio Ghibli office.

Memorabilia from past hits are among the trinkets adorning the shelves of Suzuki’s Studio Ghibli office.

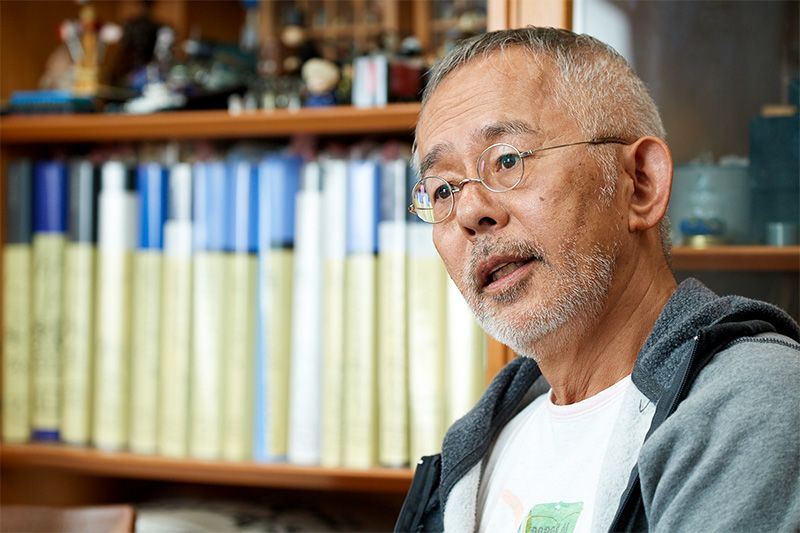

The desk where Suzuki works and occasionally watches a favorite film.

The desk where Suzuki works and occasionally watches a favorite film.

Suzuki’s advice caused Miyazaki to shift course more than once over the years. In fact, such a shift was behind his last feature film, The Wind Rises.

“Miyazaki wanted to make a sequel to Ponyo [2008],” says Suzuki, “but I wasn’t keen on that.” At the time, a magazine targeting model hobbyists was carrying a serialized manga by Miyazaki based on the life of Horikoshi Jirō, designer of the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter aircraft. Suzuki thought the story would make for an interesting feature film. It was an opportunity to see how Miyazaki, as a film director, would handle the subject of the war. Although reluctant at first, Miyazaki eventually saw the merit in Suzuki’s proposal.

The Wind Rises was to be Miyazaki’s swan song, as The Tale of the Princess Kaguya was to be Takahata’s. Suzuki has jokingly referred to the films as severance packages for the two directors. “I really just wish they would hurry up and die,” he quips with characteristic irreverence.

“I met them in 1978, so it’s been thirty-eight years,” he goes on. “When you’ve been with people that long, you want to stick with them to the end.

“The three of us had a chance to talk together after the premieres of The Wind Rises and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. I mentioned that I had hoped we could hold both premieres on the same day and get them out of the way, but it didn’t work out, and I joked that in the future it would be helpful if they could coordinate—for example, dying on the same day so that we could make do with just the one funeral. Takahata laughed, but Miya-san looked at me like he thought maybe I meant it.”

Miyazaki and Takahata have a personal friendship and professional rivalry extending back some 50 years. Though bound by ties of affection and respect, they are both fierce individualists with highly distinct personal styles. As someone who has won the respect of both masters in the process of producing one acclaimed film after another, Suzuki has earned the right to tease.

The Red Turtle: A Long-Awaited Multinational Animation

The Red Turtle, scheduled for release in Japan on September 17, is the first feature-length film of Michael Dudok de Wit, a Dutch-born animated film director based in London. Dudok de Wit’s Father and Daughter won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film in 2000. Smitten with Dudok de Wit’s aesthetic and emotional sensibility, Suzuki approached him directly about the possibility of producing a feature film. That was 10 years ago.

“He said he had never made a film longer than eight or ten minutes, so he could only embark on a feature film if Ghibli would work with him. I asked Takahata if he would help, and he immediately agreed.

“When work began on the screenplay, they were communicating back and forth between Japan and England, and progress was very slow. Then, about eight years ago, I asked Michael if he would come to Japan to work. He rented an apartment, and over a period of a month, he commuted to Ghibli and consulted closely with Takahata. In that time, the film took shape.”

The next step was finding financial backing for the project. Eventually Ghibli was able to reach an agreement to co-produce the work with Wild Bunch, a Paris-based film production and distribution services company. Studio production was completed mainly in France.

In sum, The Red Turtle is the work of a Dutch director collaborating with a Japanese producer and a production team from all over Europe. “This is the way the industry is evolving,” says Suzuki. “People from all over the world—not just from Europe but also from the Americas, Asia, Africa, and so forth—will be coming together to make one film.”

“Nowadays people from all over the world come together to make one film.”

“Nowadays people from all over the world come together to make one film.”

Brave New World of Animation

According to Suzuki, subcontracting studios in Southeast Asia already do the production work for 60% to 70% of Japanese animation. American animation has become a global enterprise as well.

“We may soon be at the point where Japanese producers and directors are heading to Southeast Asia to make films in collaboration with local teams,” says Suzuki. “I think we’re approaching the time when Japanese filmmakers will need to learn other Asian languages, such as Chinese and Thai, in order to work efficiently. Tastes will change, too, and that’s going to make things interesting. I think it’s going to be fun to see what sort of animation emerges from this borderless world.”

The paradigm shift sweeping the Japanese animation industry goes beyond production, however. In advertising, the emphasis is shifting from TV, newspapers, and corporate tie-ups to the use of social media. “I can’t deal with it,” Suzuki freely admits. As he sees it, the future belongs to people like his friend Kawakami Nobuo, the CEO of Dwango, a company specializing in Internet services and content. “It’s not just production,” says Suzuki. “Distribution and delivery of animation are going digital as well. It’s a different world from the one I knew.”

Times have changed, to be sure, but nostalgia for the era of analog is alive and well. This summer Studio Ghibli fans can revisit their favorite works from the golden age of hand-drawn animation at Ghibli Expo, an exhibition in Roppongi Hills, Tokyo.

(Originally written in Japanese by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. Based on an interview conducted on June 13, 2016. Photos by Ōkōchi Tadashi. )▼Further reading

Future Unclear for Japanese Animation after Miyazaki Hayao’s Retirement Future Unclear for Japanese Animation after Miyazaki Hayao’s Retirement |  Nature and Asian Pluralism in the Work of Miyazaki Hayao Nature and Asian Pluralism in the Work of Miyazaki Hayao |

anime film Miyazaki Hayao Studio Ghibli Takahata Isao Suzuki Toshio The Red Turtle