Lafcadio Hearn’s Journey to the Center of the Japanese Spirit

History Culture Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Timeless Views

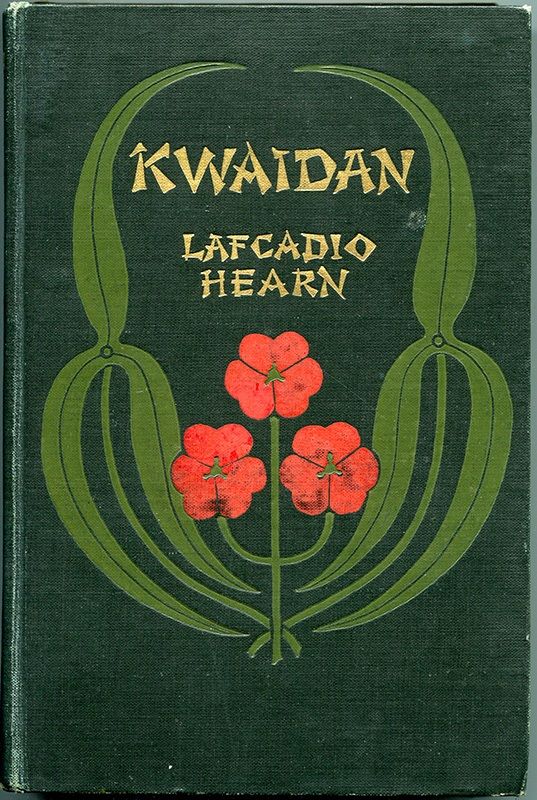

Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904) is best known for his collection Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, which includes classic Japanese ghost stories and horror tales like “The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Hōïchi” and “Yuki-Onna.” The anthology is a timeless work of art read widely in the country and around the world. In it, Hearn displays his skill as a writer and the perceptive vision of a thinker interrogating materialist civilization.

The first edition of Kwaidan, published in 1904.

The first edition of Kwaidan, published in 1904.

Here are four statements by Hearn regarding his adopted home of Japan.

I think the future greatness of Japan will depend on the preservation of that Kyushu or Kumamoto spirit, the love of what is plain and good and simple, and the hatred of useless luxury and extravagance in life.”(*1)

The real religion of Japan, the religion still professed in one form or other, by the entire nation, is that cult which has been the foundation of all civilized religion, and of all civilized society,—Ancestor-worship.(*2)

Japanese education attaches too much importance to rote memorization and does not cultivate the imagination.” (*3))

When one reflects that for thousands of years Japan has suffered [natural disasters] in precisely the same way, it is difficult not to believe that such extraordinary conditions have had no effect upon national character.” (*4)

Each brings into sharp relief issues that continue in contemporary Japan, identifying distinct characteristics of Japanese culture. Yet there is no contradiction between these views and his retelling of more than 70 of the country’s ghost stories over his lifetime. He found “a kind of truth” in the literature of the supernatural and was able to grasp the fundamental aspects of a foreign culture without bringing Western preconceptions to bear. Through an open mind and sharp observation with each of his senses, he could understand the essence of Japanese culture and view the country’s future prospects. This ability is deeply connected with Hearn’s background and life journey across half the globe, and the way his experiences of other cultures shaped his thinking to oppose an anthropocentric view of the world.

From Ireland to Japan

In 1850, Patrick Lafcadio Hearn was born in Lefkada in the Ionian Islands of Greece. His father Charles was an Irish surgeon in the British Army and his mother Rosa was from Kythira, another of the Ionian Islands.

The Greek island of Lefkada, where Hearn was born.

The Greek island of Lefkada, where Hearn was born.

When he was two, they moved to his father’s family home in Dublin, Ireland. His mother Rosa, however, suffered from mental distress and returned to Greece when he was four years old. He would never see her again. Hearn was raised by his father’s aunt Sarah Holmes Brenane, although his daily care was the responsibility of his nurse Catherine Costello, who was from Connaught, which had the richest Celtic oral tradition in Ireland. He later studied at a seminary in Durham in the north of England, but while there he lost the sight in his left eye after it was hit by a cricket ball. His great-aunt’s bankruptcy led to him leading a vagrant life in London before studying for a time in northern France. At the age of 19, he emigrated on a solo journey to Cincinnati in the United States.

Hearn and his great-aunt Sarah Holmes Brenane.

Hearn and his great-aunt Sarah Holmes Brenane.

Hearn rarely spoke of his time in Ireland, but in later life he wrote in a letter from Tokyo to the Irish poet William Butler Yeats, “I had a Connaught nurse who told me fairy-tales and ghost stories. So I ought to love Irish Things, and do.” It goes without saying that his affinity for and acceptance of Irish spirits paved the way for his subsequent investigation into Japanese ghost stories.

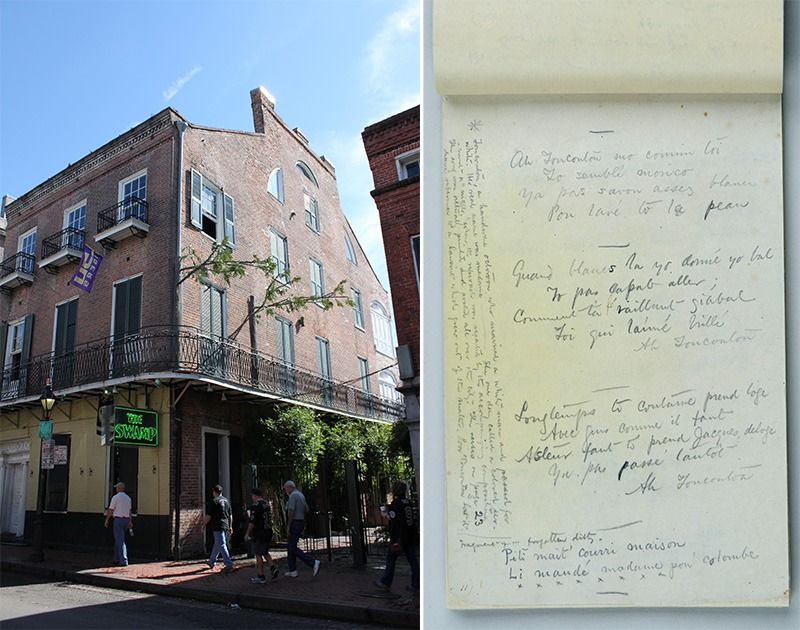

He raised himself out of penury in Cincinnati to become a journalist, but his marriage to a mixed-race woman called Alethea Foley was a violation of Ohio’s law against miscegenation. After divorcing from Foley, he moved to New Orleans, where he was fascinated by the fusion of French, African, and Native American traditions in Creole culture. He published a dictionary of Creole proverbs and the world’s first Creole cookbook. He also made frequent visits to Marie Laveau, popularly dubbed the Voodoo Queen. He became engrossed in the study of the spells and folk beliefs of Voodoo, which had its origins in Africa and had laid down local roots.

While in New Orleans, Hearn lived in rented rooms at 516 Bourbon Street (left); Hearn’s notes from journalist days in New Orleans. (© Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

While in New Orleans, Hearn lived in rented rooms at 516 Bourbon Street (left); Hearn’s notes from journalist days in New Orleans. (© Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

Hearn’s reporting on the New Orleans World Fair of 1884–85 brought a chance encounter with Japanese culture. He bought two volumes of Japanese myths abridged into French. This is when he began to take an interest in the foundational culture of the unknown East. He then spent two years in the French-controlled Caribbean island of Martinique, where painter Paul Gauguin was living in the neighboring town. He compiled his observations of the island’s folk customs into his Two Years in the French West Indies.

After returning to New York, he encountered Percival Lowell’s The Soul of the Far East. He was also captivated by Basil Hall Chamberlain’s Ko-Ji-Ki, an English translation of Japan’s eighth-century collection of foundation myths,(*5) which he borrowed from an editor of the magazine Harper’s. He decided the time was ripe to make his journey to Japan. On April 4, 1890, he sighted Mount Fuji for the first time from the deck of the Abyssinia and stepped on to shore at Yokohama. He was 39 years old.

(*1) ^ The Future of the Far East,” a lecture given in Kumamoto, Kumamoto Prefecture, on January 27, 1894.

(*2) ^ Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation, 1904.

(*3) ^ The Value of the Imaginative Faculty,” a lecture given in Matsue, Shimane Prefecture, on October 26, 1890. (Paraphrased from available resources; original text no longer available.

(*4) ^ Earthquakes and National Character,” an article in the Kobe Chronicle on October 27, 1894.

(*5) ^ Chamberlain was a British linguist who arrived in Japan in 1873, taught at Tokyo Imperial University from 1886–90, and contributed to the establishment of modern studies of the Japanese language.

Izumo, Land of the Gods

Hearn initially traveled to Japan as a special correspondent for Harper’s, but the contract was annulled and he chose to settle down locally. With help from Hattori Ichizō, a ministry of education bureaucrat he had met at the New Orleans World Fair, and Chamberlain, he obtained a teaching position at Shimane Prefectural Common Middle School in Matsue. He arrived there on August 30, 1890. At the front of Ko-Ji-Ki there was a map showing “The World as Known to the Japanese of the Mythical Era,” with the words “Idzumo Legendary Cycle” written across it. Hearn must have felt great joy and enthusiasm at his chance to live near Izumo, the setting of Japan’s early myths.

In Matsue, Hearn found a kindred spirit in vice-principal Nishida Sentarō, among others. In the dreamlike, gentle sunlight and rich variations in the surface of Lake Shinji, he discovered an Eastern beauty he had not previously encountered. He also began to live with Koizumi Setsu, the daughter of a samurai family in Matsue introduced to him by Nishida. Hearn originally heard many of the famous tales he later retold in Kwaidan from Setsu.

He was warmly welcomed to Izumo Taisha Shrine by the chief priest Senge Takanori, becoming the first Westerner to enter the honden, or main sanctuary structure. He later made two more visits to study Shintō through direct experience. Partly prompted by a request from Chamberlain, he began collecting protective amulets from many shrines in Izumo, sending more than 80 to Edward Burnett Tylor, the head of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum, whom he loved and respected.

Milk delivery was already established in Matsue, and the chef of a Western restaurant brought steaks to his home. He could also find beer at a local pharmacy. Although a Japanophile, it took time for Hearn to accustom himself to local cuisine, so with some irony, he found solace for mind and body in this Westernized environment.

Investigating the Japanese Spirit

Stunned by the cold of Matsue in winter, after a year and three months Hearn set off on fresh travels. He lived successively in Kumamoto, Kobe, and Tokyo. While in Kobe, he gave greatest consideration to his future home life, marrying into Setsu’s family in 1896 and taking the Japanese name Koizumi Yakumo. As he cheerfully explained in a September letter to his friend Elwood Hendrick, “‘Yakumo’ is a poetical alternative for Izumo, my beloved province, ‘the Place of the Issuing of Clouds.’ You will understand how the name was chosen.”

Lafcadio Hearn (left) with his family in Kobe. (© Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

Lafcadio Hearn (left) with his family in Kobe. (© Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

From his Kumamoto days onward, he encountered a Japan that had lost its humility and was pressing forward with Westernization, modernization, and militarism; he had sensed none of these in Matsue. His disappointment brought with it a mature, objective outlook on the country. Reducing his fieldwork, he shut himself in his study to investigate the Japanese view of kami (gods). At the same time, he listened to Setsu’s ghost tales, becoming engrossed in creating versions imbued with a literary spirit.

Many in the West saw Shintō, with its lack of religious texts or precepts, as heathen. Hearn, however, believed that Shintō lived not in books but in Japanese people’s hearts, deeply resonating with a form of folk spirit that lay at the foundations of superstition, legend, and the occult. He found himself sympathetic to the notion that sometimes living people could become gods and the broad-minded view that could accept spirits living in artificial objects.

Reading Hearn in Occupied Japan

In Hearn’s final work, Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation, he wrote a history of the Japanese spirit. He took ancestor worship as passing through stages from a “domestic cult” via a “communal cult” to a “state cult,” in which imperial ancestors are worshiped at Ise Shrine. In other words, he saw ancestor worship as inseparable from the reverence shown to the emperor. One of the later readers to agree with this assessment was US General Bonner Fellers, who served under General Douglas MacArthur during World War II.

US Army General Bonner Fellers.

US Army General Bonner Fellers.

Fellers read all of Hearn’s works and, shortly after arriving in Japan as part of operations immediately following the end of the war, he sought out his descendants and visited his grave. The general contributed to the drawing up of a memorandum on the imperial institution and a memoir by Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito). He also proposed that the emperor should not be subjected to the Tokyo Trial, and that instead his authority should be applied in a new democratic direction. This would avoid removing the Japanese people’s spiritual anchor. Fellers made a great contribution to the realization of today’s symbolic role for the emperor.

The MacArthur Memorial, a museum in Norfolk, Virginia, houses 5,000 of the general’s personal books, including seven written by Hearn. Works like Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation and Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan were important sources of reference during MacArthur’s time in Japan.

Lafcadio Hearn Japanese Gardens in Tramore, Ireland. Hearn often visited the coastal town together with his great-aunt when he was a young boy living in Dublin. It consists of 10 gardens introducing Hearn’s life.

Lafcadio Hearn Japanese Gardens in Tramore, Ireland. Hearn often visited the coastal town together with his great-aunt when he was a young boy living in Dublin. It consists of 10 gardens introducing Hearn’s life.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 28, 2018. Banner photo: Lafcadio Hearn in 1889. Photographs courtesy the Koizumi family, unless otherwise stated.)