Stripped-Down Funerals and Untended Graves: Dealing with Death in Aging Japan

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Later Deaths in Greater Numbers

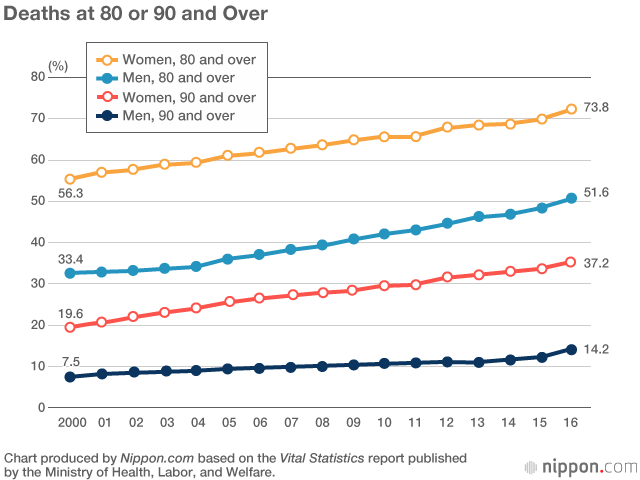

Since the turn of the century, Japanese people have been dying considerably later in life. In 2000, 33.4% of men who died were 80 or over, but in 2016 that figure had risen to more than half at 51.6%. The proportion of male deaths at 90 or more increased over the same period from 7.5% to 14.2%. The age at death for women, who tend to live longer, has shown a similar upward trend. In 2000, 56.3% of female deaths came at 80 or more, rising to 73.8% in 2016, and the proportion of deaths at 90 or more went up from 19.6% to 37.2%.

In addition to dying later, Japanese are also dying in greater numbers. Total annual deaths in Japan climbed to 0.8 million in 1990, 1.0 million in 2003, and 1.3 million in 2016. Citing this rapid increase, the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research in 2012 predicted that deaths will eventually reach nearly 1.7 million in 2040.

Nowhere to Turn for Care

Caregivers step in when people are no longer able to look after themselves. In Japan, family members have traditionally been expected to take responsibility for end-of-life care and procedures to be completed after death. However, as Japanese households continue to diversify, not all families are in a position to accept such a heavy burden. As people die later, their children and siblings are also older and may not be economically or physically capable of taking on the expected caring role.

In the postwar era, households have gradually lost their multigenerational makeup and increasingly come to consist of childless couples or parents and unmarried children. Subsequently, the practice of elderly parents requiring care to move in with their children has gradually declined. In 1975, the ministry of welfare found that 54.4% of households with elderly members 65 or over included three generations of family. Since then, though, this proportion has dropped, and in 2000 it fell below the ratio for households consisting only of a married couple. In 2015, 57.8% of households with members 65 or over were either couples or—as is increasingly typical—single residents. In 1980, there were 880,000 people aged 65 or over living by themselves, but in 2015 as many as 5.9 million formed single-person households. The NIPSSR projects that this figure will swell further to 7.6 million by 2035, at which time 23.4% of elderly women and 16.3% of elderly men will live alone.

There is also a striking rise in the proportion of Japanese people who remain single throughout their lives. In 2015, 23.4% of men and 14.1% of women aged 50 had never married. Since 1990, there has been a particularly sharp increase in lifelong single men. In the last few years, many of these men have joined the ranks of the elderly. In 2015, 9.1% of men aged 65–69 had never been married. Staying single is not a problem while healthy, but when these people need nursing care, they may have no family members to turn to. Even if such responsibilities are taken on by professionals, there are still the issues of who will arrange the funeral and look after the grave after death.

Simpler Funerals

Funerals have changed over the last 20 years. Most notable is a decline in attendance. A survey by one funeral business found that on average there were 180 attendees at its services in 1996. This had fallen to 100 in 2005 and 46 in 2013, constituting a fourfold decrease in just 17 years.

A 2005 survey by the Fair Trade Commission showed that 67.8% of people in the funeral industry said attendance had dropped compared with five years earlier. In another survey in 2016, 86.8% responded that attendance had fallen.

The main reason for the decrease is the later average age of death. In the past, both the deceased’s family and other mourners were particularly concerned about putting on appearances. When the children of the deceased are over the retirement age of 60, however, it is natural for attendance by work colleagues to drop and for small-scale funerals to become more common. Some families do not hold formal ceremonies, only gathering in small numbers to spend an evening together at a simple cremation. In the 2016 FTC survey, 26.2% of people in the industry answered that this practice, known as chokusō, is becoming more common. Although only 5.5% of funerals across the country are chokusō, there is great regional variation. In Tokyo more than one in four funerals already fit this description.

Untended Graves

Graves themselves have changed a lot. Graveyards with a bright atmosphere, such as those in parks surrounded by grass and flowers or where trees are planted instead of placing markers, are becoming more popular. Rather than formal references to family ancestry, graves increasingly feature inscriptions of words like “love” (愛) or “thank you” (ありがとう), and more interest is being shown in design. The growing trend since the 1990s of choosing one’s own grave while still healthy is a factor in this shift.

Japanese graves have traditionally been shared and passed down through a family, with successive generations taking responsibility for looking after them. However, the tendency toward smaller families and the decline in marriage has put a strain on this cultural practice, and increasingly graves are becoming neglected.

The population drain from the countryside to big cities means the problem is particularly acute in smaller municipalities and rural areas. Surveys conducted in Kumamoto Prefecture and Takamatsu in Kagawa Prefecture revealed that over one in four graves were no longer being looked after.

Some people have moved distant ancestral graves closer, so that they are easier to tend. Even those with children may choose to avoid placing a burden on the next generation by deciding to be buried in common graves that do not require family members to look after them. Some do not even want a grave at all. There is no legal problem with keeping cremated remains at home or disposing of them properly in the sea or on a mountain.

Approaches in Taiwan and Sweden

How are funerals handled in other countries? Taiwan has a long-standing tradition of mutual aid within families and religious groups, but it is undergoing the same kind of demographic shift as Japan. It too faces new social problems like the limit to care within families and increasingly solitary elderly people.

In the last few years, major Taiwanese cities like Taipei, New Taipei, Taichung, and Kaohsiung have been overseeing combined funerals for several people at a time that cut down effort and cost for the family of the deceased.

In Taipei, the system is financed by donations from citizens and covers funerary expenses like transportation, the coffin, enshrinement, funeral services, and cremation. When the service was introduced in 2012, funerals were only held once a week and there were 832 burials in total. In 2017, they were held three times a week with a total number of 1,594 burials.

Some form of grave is also provided free of charge, and each municipality offers environmentally friendly options. In Taipei, for example, no payment is required for tree planting or scattering of remains in a garden or the sea. This last option is only available through the municipality, and in 2017 a designated boat belonging to the city made nine trips between March and November.

Sweden has a kind of funerary tax called begravningsavgift that is used to pay for services and related expenses. Individuals do not save specifically for their own funerals, but instead pay into a pool used for all citizens.

In the capital Stockholm the tax is deducted directly from the salaries of residents, but in other municipalities members of the Church of Sweden include the amount in their monthly payments to the body. Payments vary depending on the municipality and the size of the church. As well as funeral expenses, the money pays for a gravesite for 25 years. Catholics, Muslims, atheists, and others who do not belong to the Church of Sweden also contribute through salary deductions.

Japan faces a new issue of citizens dying with nobody to take charge of their funerals and remains. When society and families undergo transformation, it is only natural that funerals should too. This needs to be seen as an issue for society as a whole rather than just for individuals and families.

(Originally published in Japanese on February 22, 2018. Banner photo: A grave made from processed cardboard for home use. Photo taken at a funeral industry trade show at Tokyo Big Sight in 2015.)