Remarkable Recovery: The Modern History of Japan’s Environment

Japan’s Forests: From Lumber Source to Beloved Resource

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Government-Led Destruction of the Forests

There was a sharp decline in demand for firewood and charcoal from the mid-1950s as energy needs were increasingly met by fossil fuels. At the same time, demand for construction materials, including pulp lumber, soared as the Japanese economy rapidly expanded. To cope with this, the Forestry Agency launched a massive forest-expansion campaign to clear-cut buna forests and replant them with fast-growing conifers like Japanese cedar and cypress, which would provide more economical lumber for building. This policy, it was believed, would ensure future supplies of lumber.

Venerable buna more than a century old were relentlessly cut down over a broad area. It only takes five minutes for a chainsaw to cut through a tree 50 centimeters in diameter, but new plantings cannot grow fast enough to replace the felled trees. And in the snow country of the northeastern regions, the newly planted conifers failed to grow. Needless to say, the campaign was an utter failure.

Conifer forests are densely planted and then periodically thinned to ensure that the trees grow straight and tall. The lower branches must be pruned for knot-free, high-quality timber.

A demonstration of Kitayama sugi (Japanese red cedar; Cryptomeria japonica) branch trimming at the fortieth National Tree Tending Ceremony, held in October 2016. (© Jiji)

A demonstration of Kitayama sugi (Japanese red cedar; Cryptomeria japonica) branch trimming at the fortieth National Tree Tending Ceremony, held in October 2016. (© Jiji)

The Forestry Agency’s expanded forest-planting campaign was in fact a government-authorized program of forest destruction. It was around this time that people in the lumber industry started talking about the “buna massacre.” As a result of this policy, artificial forests that once accounted for only 27% of Japan’s total forest land had grown to exceed 44% by 1985.

During this time, it is estimated that as many as 17 million buna trees were “massacred.” On a global scale, in which artificially planted forests account for only 3.5% of all forest land, Japan’s high share is indicative of the rapid pitch at which reforestation proceeded. Now the reforested areas are in dire need of thinning, but there are not enough people to do the work, and so they remain untended.

Misguided Deregulation

Humans are not the sole beneficiaries of forest bounty—innumerable living creatures depend on forests for food and shelter. But the destruction of the native forests has deprived them of their natural habitat while the saplings and bark of the replanted conifers provide fodder only for deer and Japanese serows whose populations have burgeoned as a result. Another effect has been to drive black bears down into areas with human populations in their search for food to replace the acorns that are no longer to be found in the reforested mountains.

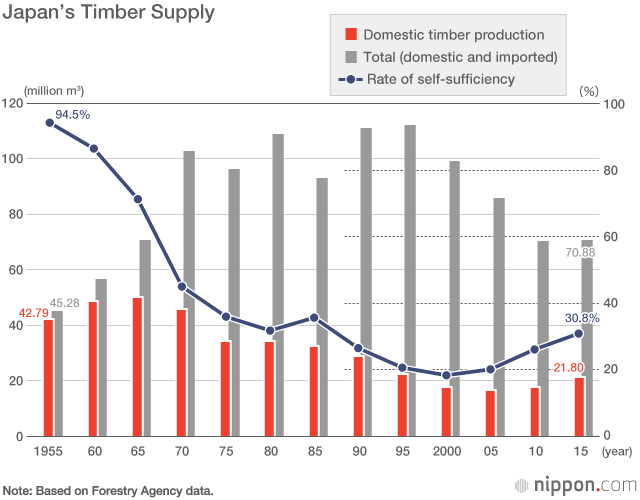

Despite the problems with the reforesting campaign, economic growth spurred the demand for domestic lumber, causing prices to soar. In an effort to correct this, the government in 1964 opened the market to cheaper imports, effectively undercutting the domestic logging industry. At one point, Japan’s self-sufficiency in lumber—which had been as high as 90% in 1950—plummeted to less than 20%.

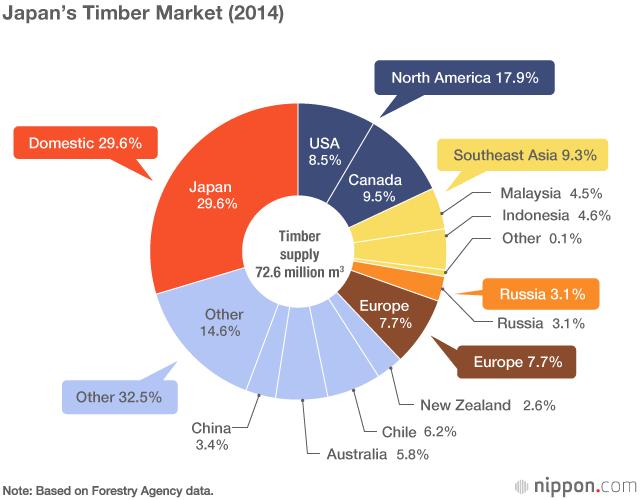

Ironically, the large-volume imports of foreign lumber led to the export of Japan’s forest-destruction policies to other countries. Japan’s postwar reconstruction created an insatiable demand for foreign lumber in the country. The first to go, during the 1960s, were the mountain forests of the Philippines. After they had been laid bare, Japanese importers targeted the forests of Indonesia, the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak, and Papua New Guinea. So destructive was the Japanese approach to logging that Japan was internationally criticized for depleting the forests of Southeast Asia.

The Demise of the Forestry Industry

The value of Japan’s forestry production has been steadily declining since it peaked at around ¥1.158 trillion in 1980. By 2014, it had dropped to less than ¥450 billion. Over this time, the number of forestry workers—146,000 at the peak of production—has dwindled to a third of its former level. This dwindling of the labor force has caused untended forestland to continue to grow, and in many cases to become a cause of the flooding and landslides that seem to occur with increasing frequency every time there is a typhoon or heavy rainfall.

Currently, high global demand for lumber has pushed up the price of imported lumber, while domestic Japanese cedar prices are only about one-fourth what they were in 1980, following some extreme fluctuation in the meantime. Japanese cedar today is laughingly referred to as the “world’s cheapest lumber.” Ove the past decade, the domestic lumber supply has remained unchanged. The government’s massive reforestation project has compelled forestry cooperatives and forestry workers to rely on subsidies and grants, and this dependence continues even though the artificial forests have reached their optimal rotation age. It is truly ironic that Japan’s forestry industry is atrophying in a land so rich in forest resources.

The Riches of Japan’s Forests

Japan’s buna forests are widely distributed from southern Hokkaidō to Kagoshima Prefecture and account for 17% of the country’s natural deciduous broad-leaved forests. These magnificent trees average 30 meters in height and 1.5 meters in chest-height diameter, and the movement to save them has led to 34 municipalities selecting the buna as their symbol tree.

A deciduous tall tree of the buna family. Commonly found at relatively high elevations along the Japan Sea side of the country. Pale yellow flowers bloom in May. (© Anezaki Kazuma)

A deciduous tall tree of the buna family. Commonly found at relatively high elevations along the Japan Sea side of the country. Pale yellow flowers bloom in May. (© Anezaki Kazuma)

While buna has a beautiful grain, it tends to rot quickly and warps easily after processing, which is why, of the several kanji that can be used for the word tree’s name, the one most commonly used is 橅, an original Japanese kanji meaning “useless tree.” Up to the latter half of the twentieth century, buna logs were used primarily to grow mushrooms and as firewood. Other uses were plywood, toys, and the keys for some musical instruments. It is only with advances in processing in recent years that buna wood has come to be used for furniture and flooring.

A Hunter’s Drive to Preserve the Forests

Tsuchiya Norio was the first person to introduce me to the buna forests. He was so enamored of the broad-leaved tress of Tōhoku that he lived a life of near self-subsistence in their midst, only descending from the mountains in the worst months of the winter. He is the one who made it possible for me to see the secluded buna forests of Tōhoku for myself. It was 1970 when Tsuchiya was notified of a crisis situation by Shida Tadanori, a matagi hunter living in the Ōisawa district of Nishikawa, Yamagata Prefecture, in the foothills of the Asahi Mountain Range.

Shida was born in 1917. He made his livelihood by hunting bear and harvesting wild mountain vegetables. He was well-known as the last of the traditional matagi hunters. Shida also managed mountain huts for climbers and served on the local rescue squad. In his final years, he was a strong advocate for conserving the buna forests and served as a guide to mountaineers and forest researchers.

Matagi Shida Tadanori of Nishikawa, Yamagata Prefecture, in 1983. (© Anezaki Kazuma)

Matagi Shida Tadanori of Nishikawa, Yamagata Prefecture, in 1983. (© Anezaki Kazuma)

I always enjoyed Shida’s stories of the mountains when I stayed at his home. His deep knowledge of wild animals and the forests was phenomenal. Ōisawa is a small hamlet of only 230 people, but it has its very own nature museum, well stocked with items—some of them very rare—provided for the most part by Shida.

Shida passed away in May 2016 at the age of 101. Just two years before his death, Kadokawa Shoten published his biography, Rasuto matagi (The Last Matagi), in which he talks about his efforts to preserve the buna forests. In 1950, when the area where he lived was incorporated into the Bandai-Asahi National Park, Shida recalls that all he had to do was step out of his house to be engulfed by the natural forest. He never thought the buna trees could possibly be decimated.

The local people cut the trees with axes and saws, but any damage they could render with such tools was minimal. Then came the 1960s, though, when contractors hired by the Forestry Agency arrived with chainsaws. Suddenly, huge lumber of trees were being felled. In no time at all, everything up to an elevation of 1,000 meters had been cut clear.

A hillside is left barren, only a small strip of trees left standing along a logging road. (© Anezaki Kazuma)

A hillside is left barren, only a small strip of trees left standing along a logging road. (© Anezaki Kazuma)

The clearing of the forests threatened the livelihood of the local people who had depended for generations on the bounty of the mountains. Wild mountain vegetables were no longer to be found and hungry bears made their way down to the settlements in search of food. Shida and others pleaded with the mayor to limit the cutting and repeatedly petitioned the local Forest Management Office (today’s Regional Forest Office), but the response was tepid.

It was this background that eventually brought Shida to me. The year was 1971, and 85 groups scattered throughout the country had just joined forces to form a national union for nature conservation headed by a man named Aragaki Hideo. I was involved in this movement as well.

Shida attended to first meeting of the union and immediately thereafter set up a group to protect the buna forests of the Asahi Mountain Range. Those of us in the capital set up a Tokyo branch for the group and rallied support from the Nature Conservation Society of Japan and similarly minded organizations. The deforestation continued, but Shida persevered, even meeting directly with the Forestry Agency director-general. At long last, the logging stopped in 1976.

This brought an end to an era in which it was unheard of for local residents to protest the decisions of the Forest Management Offices. We must never forget the courage it took for people like Shida and his neighbors to stand up to the government.

Growing Public Sentiment for the Forests

The movement against the deforestation policy grew and spread throughout the country. In 1977, the agitation reached a peak in a vigorous protest against the logging of national forest land located inside the Shiretoko National Park in Hokkaidō. Led by the local mayor, a movement arose to have individuals buy up and pool their portions of the land to create a national trust. I joined the drive and bought my own bit of forestland. By 2010, the movement had achieved its goal, and trees were planted on a total expanse of roughly 861 hectares. These new plantings will grow into lush forestland for future generations.

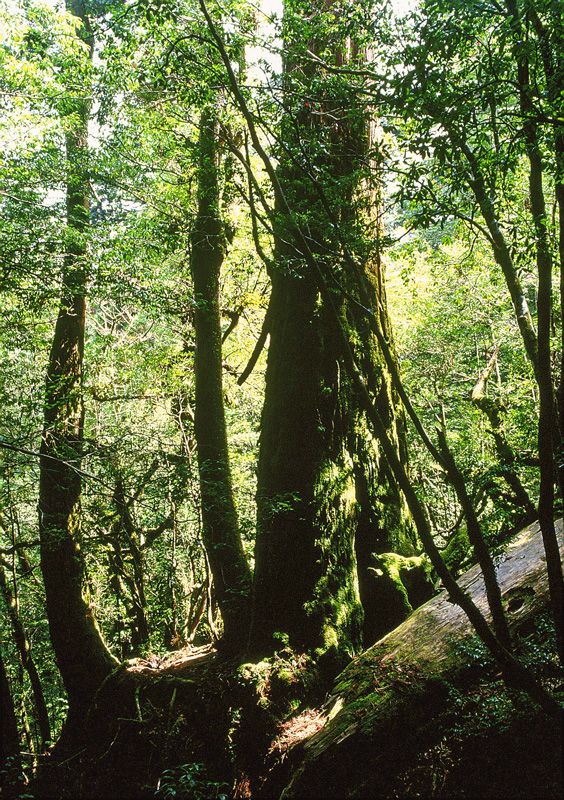

Down south in Kyūshū, people were rallying to preserve the Japanese cryptomeria, known as yakusugi, on the island of Yakushima. Ancient cryptomeria, many estimated to be more than 1,000 years old, can be found on the island. The logging of yakusugi dates back to the sixteenth century. In the Edo period (1603–1868) yakusugi roof shingles were shipped to the capital as annual tribute. Rich in resin and impervious to rot, yakusugi was a popular wood for building.

There had been a ban on logging yakusugi, but in 1957, the Forestry Ministry lifted the ban, and in response to the growing demand for lumber began logging yakusugi in the 1960s. The Agency employed clear-cutting techniques that left whole hillsides barren and bereft of old-growth trees. But then in 1966, at the peak of the deforestation drive, a huge yakusugi tree believed to be more than 4,000 years old—later named the Jōmon Sugi after the Jōmon period of Japanese prehistory (10,000–400 BC)—was discovered. This would become a mainstay of the tourist industry on Yakushima.

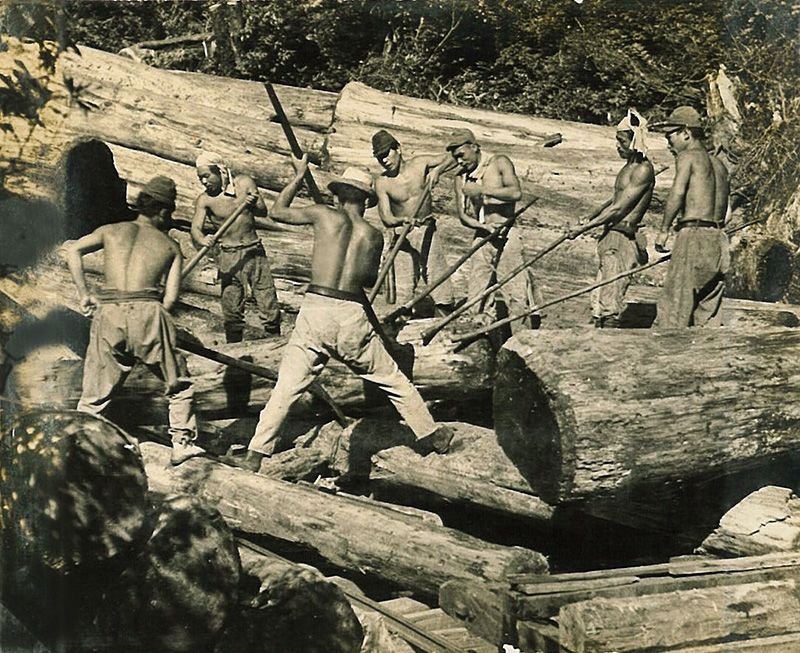

Workers gathering yakusugi logs at Kosugidani in the early postwar years. (Photo courtesy the Forest Agency’s Yakushima Forest Ecosystem Conservation Center)

Workers gathering yakusugi logs at Kosugidani in the early postwar years. (Photo courtesy the Forest Agency’s Yakushima Forest Ecosystem Conservation Center)

Local and former residents of Yakushima feared that the ancient denizens of their beloved forests would be toppled. In 1972 they formed the Society to Protect Yakushima. At the time, however, logging was the primary industry for the area, and the society was isolated with little support.

Attitudes changed, however, when disaster struck in 1979 with a huge landslide caused by deforestation, and again when it was learned in 1980 that there were plans to build a petroleum storage facility on the island. The local people finally had enough of the indiscriminate development being pursued by the government. Their vocal protests forced the national and prefectural governments to review their deforestation policies and implement new policies to protect and expand national and prefectural parks.

In 1980, what remained of the Yakushima natural forestland was declared a World Network of Biosphere Reserve as part of UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Programme, and in 1992, the Forestry Agency designated the whole area as a Forest Ecosystem Reserve. In 1993, Yakushima and Shirakami-Sanchi became Japan’s first Natural World Heritage Sites. The last logging of yakusugi was in 2001.

A magnificent yakusugi specimen. (© Anezaki Kazuma)

A magnificent yakusugi specimen. (© Anezaki Kazuma)

Increasing Public Scrutiny

The predecessor of the Nature Conservation Society of Japan was the Oze Marsh Conservation Union formed by scholars and mountaineers in 1949 to protest plans for a dam that would have drowned the Ozegahara marshes beneath the new reservoir. The issue was resolved in 1996 when the Tokyo Electric Power Company gave up its plan to build the dam, and the union later evolved into the Nature Conservation Society of Japan.

Since its launch, the society has prepared and submitted 191 opinion papers and petitions to prevent the destruction and indiscriminate development of the national parks, many of which include national forests. The group has battled against a wide-ranging set of development schemes, including plans to drain the marshlands of the Rishiri-Rebun-Sarobetsu National Park at the northern tip of Hokkaidō and proposals to build a new airport and cut down forests in the Iriomote-Ishigaki National Park of Okinawa Prefecture to the south.

In most cases, the society’s efforts are driven by local residents who have fought against the Forestry Agency’s arbitrary management of the national forests in their areas. The 191 papers and petitions are a testimony to the zeal for conservation of large numbers of the Japanese people. Shimura Tomoko, head of the society’s Conservation Project Division, notes that much of their success is due to the change in attitude of the government authorities who have come to take the petitions seriously. Still, she says, there are local administrative offices that tend to automatically defer to government policies.

In 2014, the Cabinet Office carried out a survey on peoples’ interest in nature. A very high 89.1% responded that they were extremely or somewhat interested in the natural environment. While I have yet to find similar surveys from other countries to make an informed comparison, having nearly 90% of the population showing a keen interest in nature is certainly among the highest rates in the world.

(Originally published in Japanese on July 19, 2017. Banner photo: The forests of Yakushima, a Natural World Heritage Site. © Anezaki Kazuma)