“Nihonshu” Now: How the Maker of Jikon Turned Mold into Gold

Guideto Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japanese food culture owes a monumental debt to a microscopic organism by the name of Aspergillus oryzae, also known as kōji-kin. The action of this magical mold, which grows on a variety of grains, is critical to the production processes that yield soy sauce, miso, and rice vinegar, three of the basic seasonings used in traditional Japanese cuisine. Kōji is also an essential ingredient of sake, along with rice and water—a use believed to date back to the Nara period (710–94). Small wonder that the Brewing Society of Japan named A. oryzae Japan’s “national fungus” in 2006.

To learn more about the vital role of kōji in sake brewing, we headed to the Kiyashō Brewery in Nabari, Mie Prefecture, to chat with owner-brewer Ōnishi Tadayoshi, whose kōji obsession produced the junmai daiginjō Jikon, one of the most sought-after labels on the sake market today.

The “fur” on the surface of this rice is Aspergillus oryzae. In a mature kōji culture like this one, the fungus filaments (hyphae) penetrate into each grain of steamed rice. (© Kiyashō Brewery)

The “fur” on the surface of this rice is Aspergillus oryzae. In a mature kōji culture like this one, the fungus filaments (hyphae) penetrate into each grain of steamed rice. (© Kiyashō Brewery)

Saving the Family Business

Jikon is truly a superstar of Japan’s sake renaissance and an exemplar of small-batch artisanal brewing. Only 30 sake stores around Japan carry the brand, and diehard fans line up to buy it. Top sake bars and izakaya attract discerning customers with prominently displayed signs announcing, “We have Jikon!” It is, without question, one of the most celebrated and popular sakes of our time.

And yet, when sixth-generation owner Ōnishi Tadayoshi took over the Kiyashō Brewery 15 years ago, at the age of 27, the family business was heading toward oblivion. Its Takasago brand was unknown outside the immediate area, and local sales were dwindling year by year. Ōnishi tried all kinds of clever promotions and marketing techniques to boost sales among locals and tourists, but nothing seemed to help.

Then one day, Ōnishi had a revelation. Tasting the acclaimed Yamagata sake Jūyondai, he was thunderstruck by its clean, fresh, sweet flavor. “All that time I was wracking my brains trying to figure out how to sell sake I was asking the wrong question," says Ōnishi. "I finally realized that the job of a brewery is making sake, and if we want people to buy our product, we just have to make it better.”

Like most breweries, Kiyashō had for many years left the actual production of its sake in the hands of an independent professional brewmaster, or tōji, and his crew. But after his revelation, Ōnishi decided to take charge of the process as a hands-on owner-brewer—even though he had no prior experience brewing sake commercially. He had taken a course in sake-brewing theory and technique designed to prepare people like himself to take over the family business (offered by the National Research Institute of Brewing, a quasi-governmental agency), and he had trained some with his own also brewery’s tōji. Most importantly, however, he was an indefatigable perfectionist with an appetite for hard work and the mentality of an engineer.

Kiyashō Brewery was established in 1818 along the historic Hase Kaidō leading to Ise Shrine.

Kiyashō Brewery was established in 1818 along the historic Hase Kaidō leading to Ise Shrine.

A Star is Born

After taking over as tōji in 2004, Ōnishi honed and systematized each stage of production with an eye to precision and repeatability. The focus of his most zealous efforts was the kōji-making process.

Kōji making is widely regarded as the most important and technically demanding step in the highly complex process of sake brewing. On a traditional sake-brewing crew, responsibility for the kōji lies either with the tōji himself or with a kōji-shi, who occupies the second-highest rung of the brewing hierarchy. Ōnishi learned the basic techniques from the previous tōji, but he chafed at the limitations of an approach so dependent on the intuitive judgment of veteran artisans. He was determined to optimize and standardize each stage of the process on a scientific basis.

He kept at it, adopting methods that made sense to him, and in 2005, the brewery launched its new brand, Jikon. With its clean, fresh flavor it quickly captured the hearts of a new generation of sake fans.

Ōnishi is unequivocal about the importance of kōji. “Kōji can make or break a sake. As I see it, one’s approach to kōji making is the clearest reflection of the kind of sake one wants to brew.”

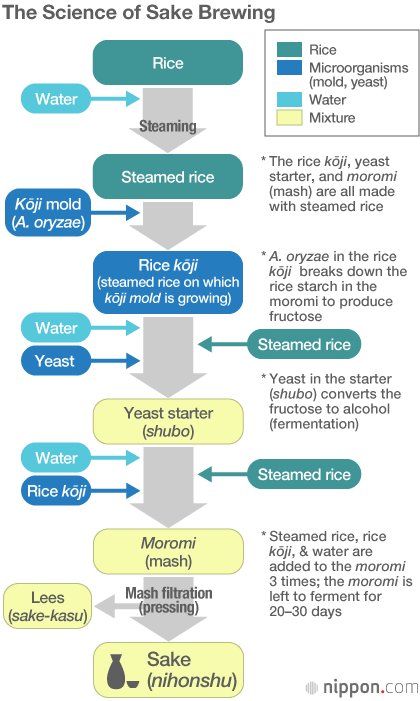

All fermented alcoholic beverages, sake included, rely on yeast (another microorganism) to produce alcohol from sugar. In the case of wine, the yeast acts directly on the juice of the grape, which has a high sugar content. But rice is mostly starch, which must be broken down into sugar before the yeast can begin the process of fermentation. A. oryzae produces enzymes that break the rice starch down into sugar so that the yeast can go to work.

At the same time, other enzymes in the kōji culture break down proteins into amino acids, which account for sake’s complex flavors and fragrances. “The kōji brings out the umami and produces a pleasant aroma,” explains Ōnishi. “But depending on how your rice kōji develops, it can also produce undesirable tastes and smells.” The challenge, in short, is to culture kōji that acts on the rice to create precisely the mixture of tastes and aromas the brewmaster has in mind. “I’m looking for a kōji that yields sweetness and umami and an elegant fragrance with a minimum of bitterness, astringency, and acridity.”

Meet the Real Sake Makers

The first step in making kōji is to acquire tane-kōji—A. oryzae spores in powder form—from a trusted producer. This powder is sprinkled over steamed rice spread on a surface in a special climate-controlled room known as a kōji-muro. Incubation takes about two days (precisely 50 hours in Ōnishi’s case).

“I think of it more as ‘cultivating’ than ‘making,’ says Ōnishi. “It’s actually the microorganisms—mainly kōji-kin and yeast—that are making the sake. Our job as human beings is to create the optimum environment for these living organisms to do what they do naturally.”

When it comes to kōji making, this boils down to carefully controlling the temperature and humidity at each stage in the culture’s growth to make things comfortable for the kōji-kin without letting things get comfortable for undesirable microorganisms. The techniques are many and varied, but they usually involve alternately covering, stirring, and dividing up the rice while carefully monitoring conditions.

Ōnishi ensures that the rice is exactly 30.5ºC when the tane-kōji is sprinkled over it. The mixture is then cooled to 29.8ºC before being transferred to wooden boxes and returned to 30.5ºC. Overnight, it is kept at a constant 43.0ºC. In order to control the temperature with such precision, Ōnishi must control other variables, such as the moisture content of the steamed rice. For this reason, he measures out the water in milliliters and uses a stopwatch to time how long the rice is kept soaking.

“I would never consider compromising,” says Ōnishi. “I mean to keep refining my technique in pursuit of my own idea of sake perfection, and Jikon will continue to evolve.”

Owner-brewmaster Ōnishi sprinkles kōji spores over steamed rice as he starts a new batch of rice kōji. Kōji making is regarded by many as the most critical and technically demanding step in the sake-brewing process.

Owner-brewmaster Ōnishi sprinkles kōji spores over steamed rice as he starts a new batch of rice kōji. Kōji making is regarded by many as the most critical and technically demanding step in the sake-brewing process.

The rice kōji is cultured by hand in a special room called a kōji-muro.

The rice kōji is cultured by hand in a special room called a kōji-muro.

In the kōji-muro, the brewers carefully monitor and control conditions at each stage of growth with the help of precision instruments, as well as their own sense of sight, touch, and smell. Good rice kōji has a rich, sweet aroma, similar to chestnuts.

In the kōji-muro, the brewers carefully monitor and control conditions at each stage of growth with the help of precision instruments, as well as their own sense of sight, touch, and smell. Good rice kōji has a rich, sweet aroma, similar to chestnuts.

Advances in science and technology, together with changes in sake-brewing culture, have revolutionized the sake industry in recent years, and nowhere is this transformation more evident than in the process of kōji making. Once dependent on the kind of subjective professional judgment that took decades to cultivate, brewers can now use precision instruments to quantify the action of A. oryzae and analyze growing conditions. Certainly publicly funded research facilities have hastened this evolution by offering technical guidance and acting as clearinghouses for brewing data and methods. But the biggest factor is unquestionably the relentless pursuit of perfection by young owner-brewers like Ōnishi. To what heights will their passion for improvement elevate Japan’s national beverage? Just wait and see.

Ōnishi samples freshly pressed sake in his brewery’s tasting room

Ōnishi samples freshly pressed sake in his brewery’s tasting room

The name Jikon is a reference to the Zen concept of living in the here-and-now.

The name Jikon is a reference to the Zen concept of living in the here-and-now.

(Banner photo: Owner-brewer Ōnishi Tadayoshi spreads his fragrant rice kōji out to dry. Photos by Sandō Atsuko, unless otherwise noted.)

- “Nihonshu” Now : Behind the Global Sake Renaissance

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: Understanding Sake Brewing

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: Types of Sake and Their Characteristics

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: Sake Tasting Demystified

- “Nihonshu” Now: Yamagata and the Sake Renaissance

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: Sake Wisdom for Guilt-Free Drinking

- “Nihonshu” Now: Japanese Brewery Senkin Rewrites the Sake Rulebook

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: The Many Faces of Sparkling Sake

- “Nihonshu” Now: Adventures in Creative Sake Pairing

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: How Serving Temperature Affects Flavor