Gankutsu Hotel: A Western-Inspired Vision Carved in Stone

Culture Architecture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

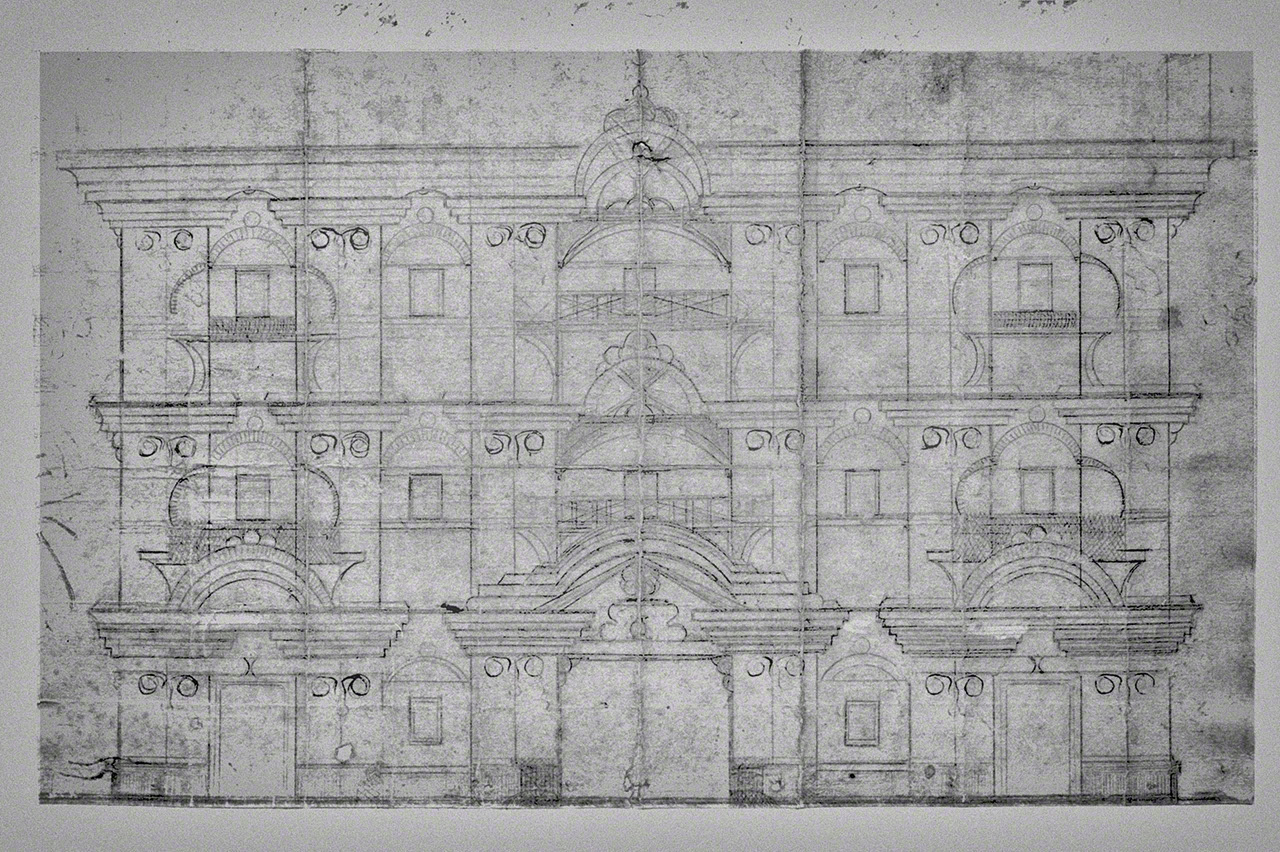

Carved into a sheer cliff face, the Gankutsu Hotel is the dream of one man, Takahashi Minekichi. A farmer, Takahashi started excavating his elaborate creation in the town of Yoshimi in Saitama Prefecture around the turn of the twentieth century, laboring for more than two decades with only simple tools.

The title Gankutsu Hotel (cave hotel) is inaccurate, as Takahashi, who named his creation Kōshōkan, did not intend for his work to lodge guests. The story that has been passed down, though, tells how neighbors discussing Takahashi’s curious behavior exclaimed that he was gankutsu hotteru (digging a cave). In time, local pronunciation shortened hotteru (digging) to hoteru (hotel), giving rise to the name the structure is best known by.

The entrance and facade of the Gankutsu Hotel (all photos from 1978).

The main entrance on the first floor.

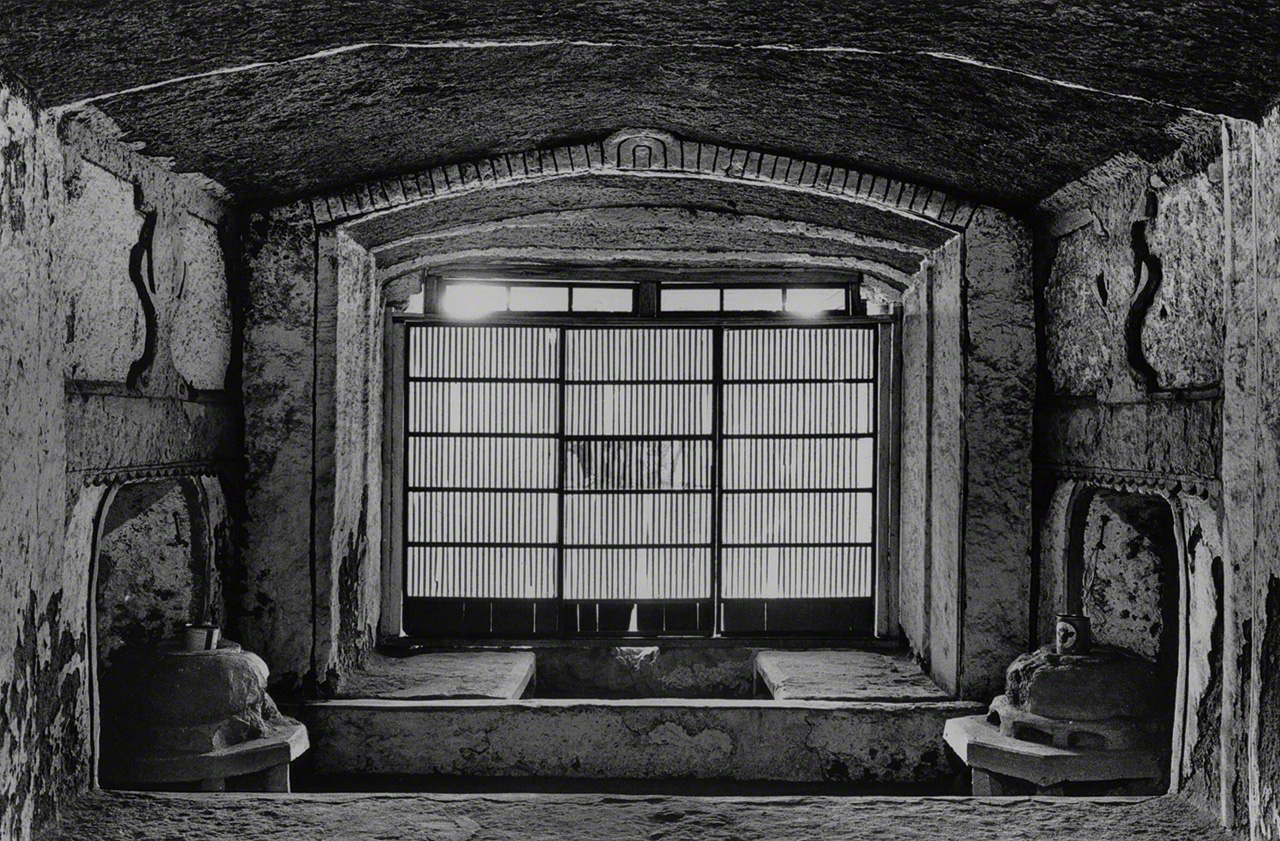

The spacious central hall boasts a delicately crafted decorative arch.

The ceiling of the central hall.

The main entrance seen from the central staircase.

Chipping Away, Inch by Inch

Little is known about what inspired Takahashi to excavate his artificial cave. However, information provided by family members and the few remaining documents suggest two possibilities.

The first is that Takahashi intended to live in the structure. The Austrian diplomat and archeologist Heinrich Philipp von Siebold, the son of early Japan scholar Philipp von Siebold, and others, had theorized that the nearby Yoshimi Hyakketsu, a cluster of small caves dating from the latter part of the Kofun period (fourth through seventh centuries CE), were dwellings. Although the caves were later recognized to be tombs, Takahashi may have been inspired by Siebold’s theory to live as the early inhabitants of the area had.

The second is that Takahashi looked to take advantage of the constant temperatures caves offer year-round. He knew from his youth that caverns were comfortable as well as ideal for purposes like storing goods. However, this is the weaker of the two theories, as it does not explain the scale of the Gankutsu Hotel, which Takahashi estimated would take multiple generations working over the better part of two centuries to complete. Whatever Takahashi’s actual motivation was, there is no doubt that he believed deeply in his vision.

Born in 1858, Takahashi came of age during Japan’s tumultuous transformation from a feudal society to a modern state. Like many of his generation, he was captivated by the influx of Western culture that promised advancements like Thomas Edison’s light bulb and Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. Enterprising by nature, Takahashi would have sensed that the country was on the cusp of a new era. A hint of this is found in an early guidebook for the Gankutsu Hotel that notes that while Takahashi received only a rudimentary education, he “enthusiastically discussed topics like architecture, physics, minerology, and philosophy.”

Takahashi Minekichi, left, and his son Taiji.

Takahashi ceremonially broke ground on the Gankutsu Hotel in June 1904 and then set to work in earnest the following September. He was 46. According to his grand vision for the project, the finished cave would be 54.6 meters wide and boast three stories. Work progressed slowly, though, as Takahashi chipped away at the rockface using only basic tools. He excavated some 30 centimeters of stone a day from a space the size of a tatami mat, or roughly 1.8 square meters. At such a plodding pace, he estimated it would require three generations laboring 150 years to complete the cave.

From the moment Takahashi started digging, the Gankutsu hotel piqued people’s interests, and it remained a curiosity until eventually it was closed to the public. Takahashi toiled away for 21 years until his death in 1925. His adopted son Taiji took up the project, working steadily, save for a hiatus due to World War II, into the 1960s. With major sections of the cave complete, from 1965 onward, Taiji, who died in 1987, focused on preserving the structure and managing the site as a tourist attraction.

Battling Stone and Groundwater

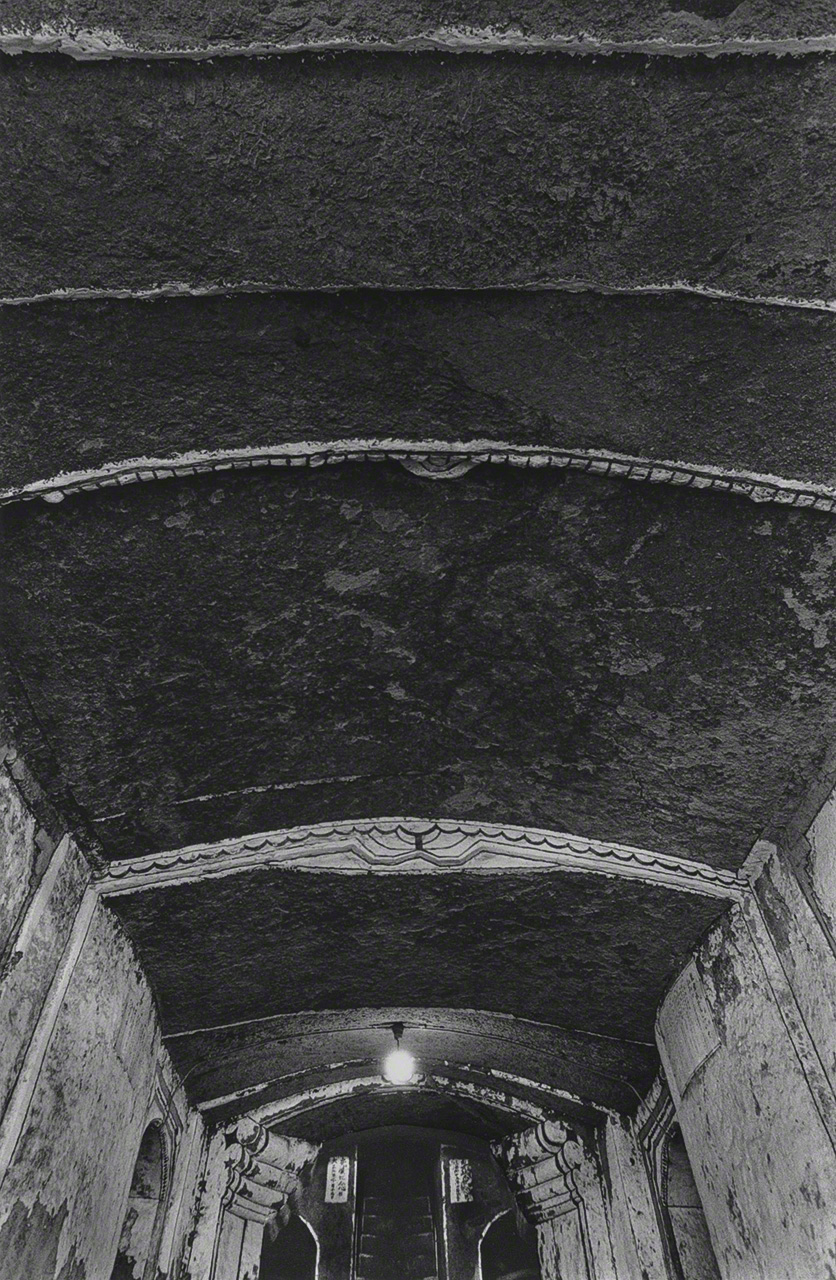

Takahashi’s original sketch of the Gankutsu Hotel shows a 21.8-meter, three-story façade of Western design. The proportions between the various parts are close to the so-called golden ratio, although it is unclear if this was intentional. The draft does not show the interior, but the symmetrical proportions suggest identical, independent wings connected by a large, central hall. Takashi might have envisioned the rooms in each wing having a specific purpose, such as the science laboratory on the first floor.

Takahashi’s original sketch of the façade of the Gankutsu Hotel.

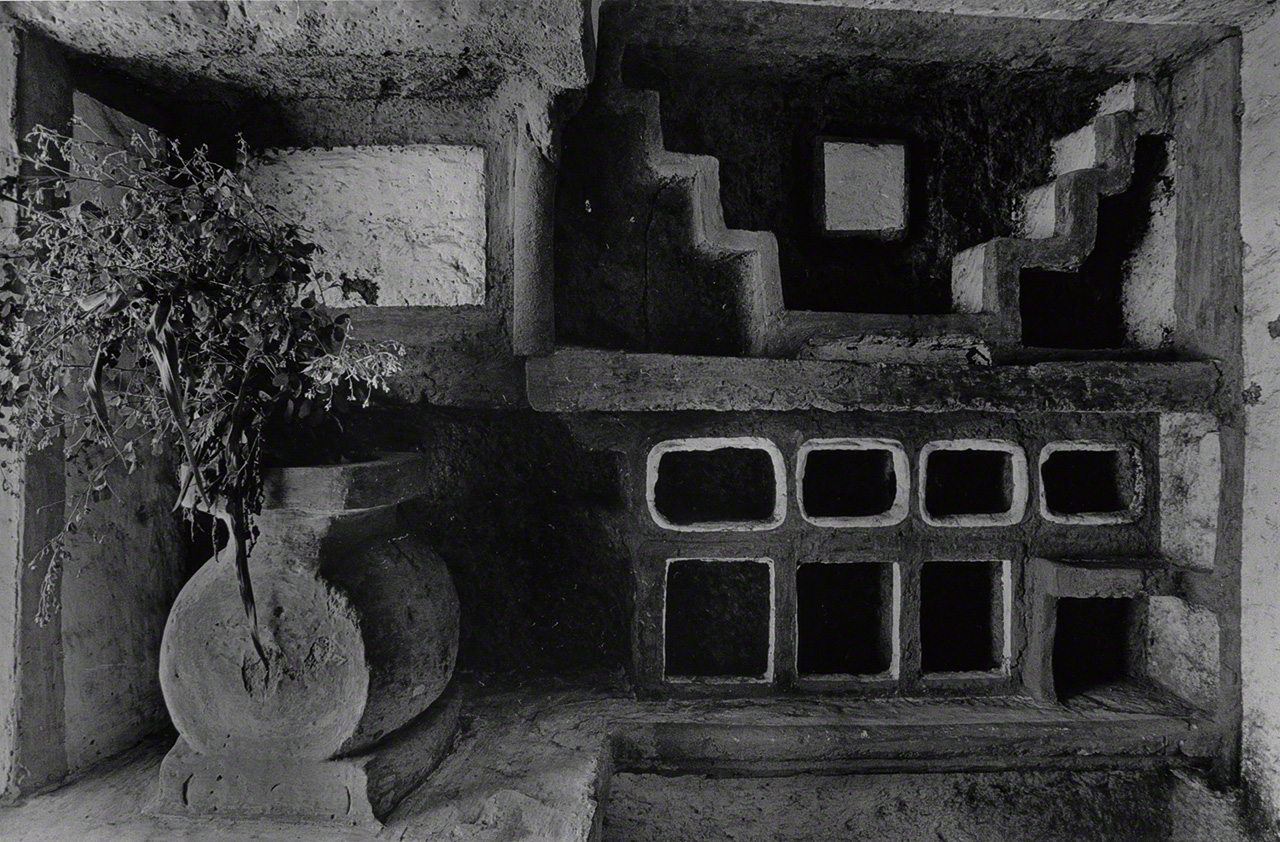

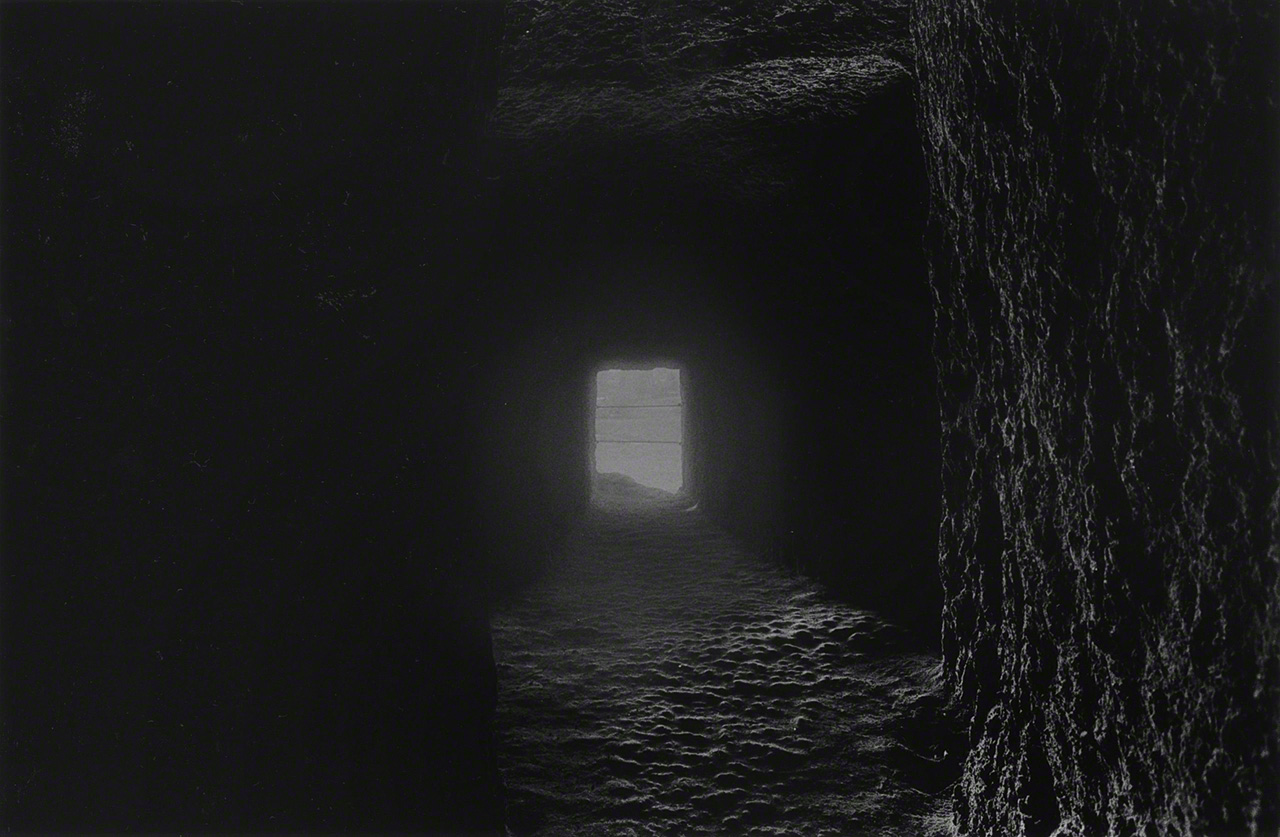

The beginnings of Takahashi’s façade are etched into the cliff face, but the work is incomplete, measuring only 20 meters wide and rising two stories. A partial outline of a window is the only hint of where the third floor would be. The cave is likewise unfinished, and the rooms and features that exist lack the symmetry implied by Takahashi’s design. These shortcomings are attributable to the challenges of excavating by hand. Although the cliff housing the Gankutsu Hotel consists of a soft, porous volcanic rock called tuff, it also contains dense strata that thwarted Takahashi’s primitive tools. Groundwater seeping from the cracks also blocked his progress in places, leaving him no alternative but to diverge from his original layout.

Takahashi’s digging tools.

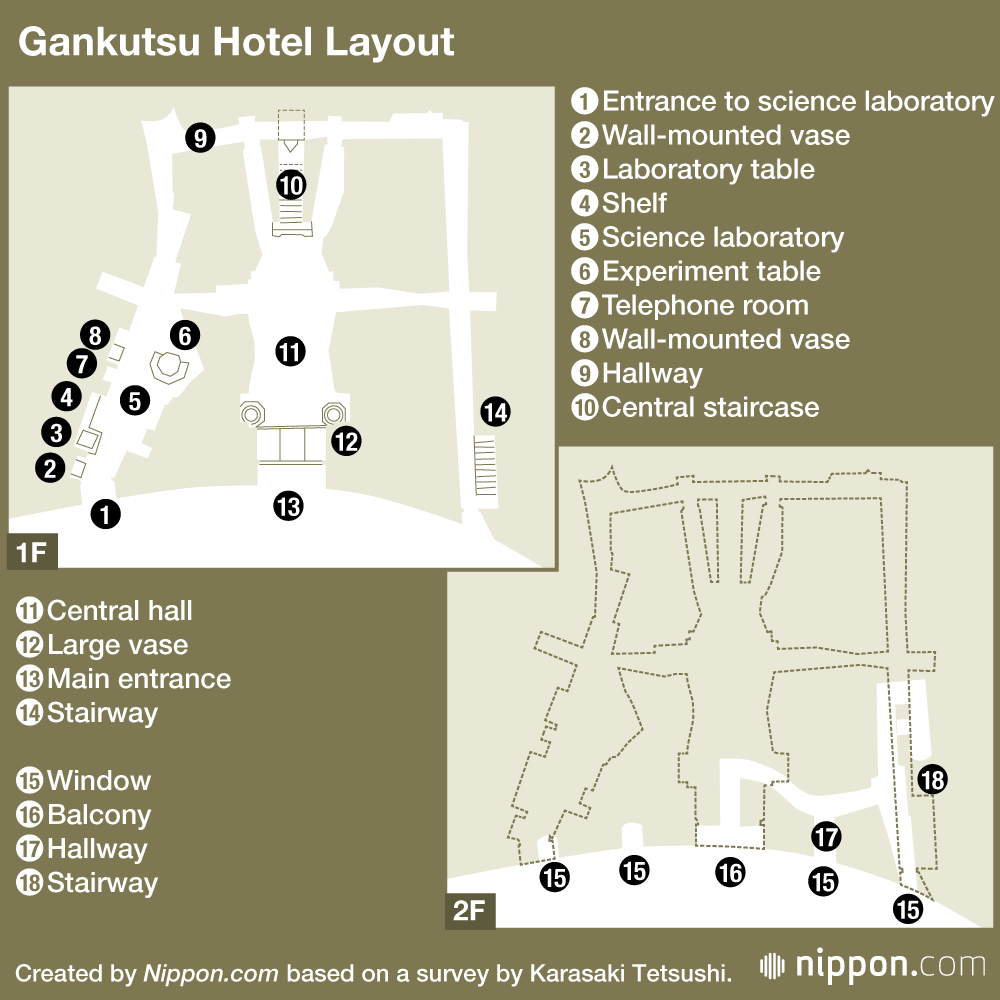

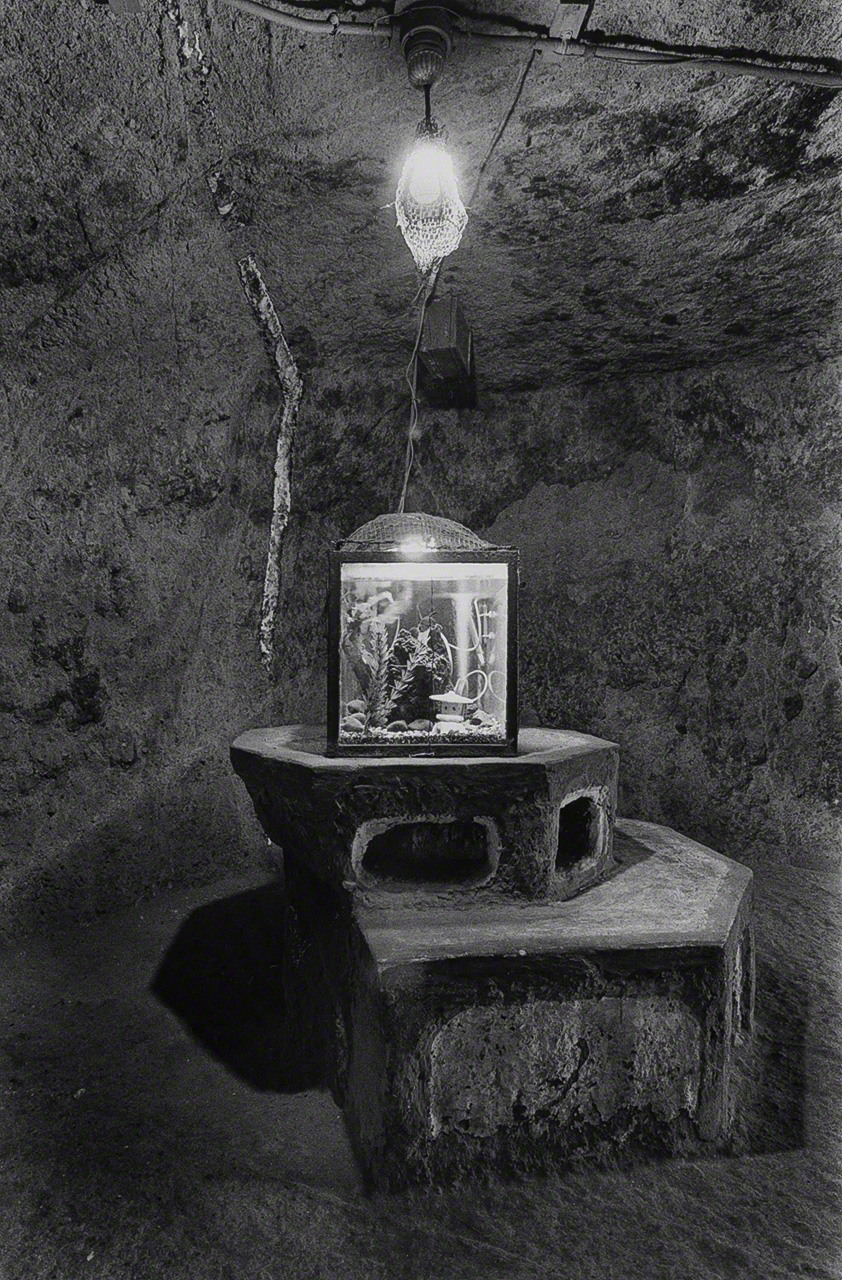

This lack of symmetry, however, does not make the Gankutsu Hotel any less impressive. In an amazing feat of skill and determination, Takahashi and his son Taiji carved all the elements of the cave from ceiling to floor, including the furnishings, from the surrounding rock. Only the first-floor door and railing on the second-floor balcony are not made from stone.

The central hall.

The back of the central hall looking toward the main entrance.

The science laboratory.

The science laboratory, looking toward the entrance.

The interior of the science laboratory.

A laboratory table.

A table and shelf in the science laboratory.

Expressing a Scientific Spirit

The Gankutsu Hotel is an enigma. Although thoughtfully designed, its features contrast with a defining characteristic of architecture, that of striking a balance between beauty and functionality. The laboratory tables, flower vases, and shelves are fixed in position, rendering them impractical, and the stone pillars and beams are superfluous substructures. It is hard to make sense of these items in practical terms, but that might have been Takahashi’s intent. The few documents that remain suggest that he wanted the Gankutsu Hotel to be a “manufactured landmark” and planned from the outset for it to be marveled at as a curiosity.

It is easy to imagine that Takahashi intended the Gankutsu Hotel to express the spirit and lifestyle of a newly emerging Western-influenced age, one that captivated his imagination. Communicating through the medium of architecture, he looked to convey Western culture as a model that brought with it the dawning of a new scientific era and the concepts of beauty, justice, and rationality. These feelings he expressed in the exacting scale, symmetrical design, and golden ratio of his Western-style three-story façade as well as in interior features like the vaulted ceiling of the central hall, the science laboratory, and the telephone room.

A first-floor hallway.

Looking down the central stairway from the second floor.

A hallway flanks the central stairway leading to the second floor.

Looking down a hallway toward a second-floor window.

The first-floor hallway. The main staircase is on the left.

A hallway opens onto the second-floor balcony.

A Crumbling Architectural Dream

The Gankutsu Hotel is an example of architecture that falls into what is sometimes categorized as naïve art, defined as a sophisticated work by an individual with little or no formal training. There are a number of well-known architectural creations of this genre around the world, including the Palais Idéal, a structure in Hauterives in southeastern France by Ferdinand Cheval (1836–1924), whose life is the subject of the 2018 film The Ideal Palace. The Watts Towers by Simon Rodia (1879–1965) in Los Angeles is another, an intricate creation that is designated a US National Historic Landmark and remains a popular tourist stop.

Japan, however, has been slow to recognize the value of such architecture. Inventor Miyake Sakae was in his seventies when he began to piece together his studio in what is now Minami Bōsō in Chiba Prefecture, a project that would occupy him for nearly two decades. Although it gained fame in certain circles, the building was demolished in 1987.

The Gankutsu Hotel is suffering a similar fate as it slowly deteriorates into dust without ever being completed. A section of the cliff face collapsed in a 1982 typhoon, and most of the façade sloughed off in another storm in June 1985. Erosion has also taken a harsh toll on both the exterior and interior of the structure, and today the only way to see Takahashi’s creation in all its splendor is in the 1978 photos by Arai Hidenori.

An iron gate now separates the Gankutsu Hotel from the outside world. Isolated, Takahashi’s grand dream remains unfinished as the cliff gradually crumbles.

(Originally published in Japanese. Text by Karasaki Testsushi; all photos © Arai Hidenori. Banner photo: The remains of the Gankutsu Hotel are just visible through the surrounding overgrowth in this photo from 2022.)