Challenges Confront the New BOJ Governor: A Revised Approach to Monetary Easing and the Risk of Surging Rates

Economy Lifestyle Society Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Monetary Easing Did Little to Boost Prices

The direction the Bank of Japan will take under new leadership is attracting the interest of markets in Japan and around the world. The primary reason for this is the way higher resource prices is increasing upside pressure on prices in Japan, which is driving the BOJ to transition away from its monetary easing “of a different dimension.”

What has placed the BOJ in this predicament? The culprit is the 2% inflation target of Abenomics, a mistaken policy from the start. While the loosening of fiscal discipline had an even larger negative impact, structural factors are to blame for the sluggishness of prices in Japan. To achieve a 2% inflation target through monetary policy alone was all but impossible.

This situation can be confirmed by examining the past movements of the rate of inflation (consumer price index). While the CPI was pushed up by 1.4 percentage points with the introduction of a consumption tax in 1989, hitting 4.9% in 1990, the average annual rate of inflation was only 0.6% during the asset bubble years of 1986–89, when Japan’s economy overheated. Prices were impacted by the Gulf War in 1990 and 1991, by the increase of the consumption tax rate in 1997, and by the sharp rise of crude oil prices in 2008. When these factors are excluded, 1985 was last time inflation exceeded 2% in any normal year up to 2013, when monetary easing of a different dimension began.

How, then, do prices differ structurally in Japan? This is readily understood by comparing the difference between the US and Japanese rates of inflation. For example, by taking inflation for August 2019 and dividing it into the rate for goods and that for services, we see that there is little difference in the rate of inflation for goods between Japan and the United States, increasing 0.3% for the former and 0.2% for the latter.

However, when we consider the rate of inflation for goods and services together (CPI for all items), prices rose 1.7% in the United States but only 0.3% in Japan. Excluding foods and energy from the CPI for all items, the rate of inflation was again higher in the United States (2.4%) than in Japan (0.6%).

This difference in inflation arises from the rate for services being higher in the United States (2.7%) than in Japan (only 0.2%). Sectors where this difference is particularly large are water and sewage services, day-care fees, long-term-care fees, university fees, and hospital services. Unlike the situation in the United States, these are sectors in Japan that are strongly influenced by the government.

What this situation tells us is that the sluggishness of prices in Japan is the result of structural factors accompanying government price controls rather than being an issue of monetary policy.

War in Ukraine Marks a Change

The environment for the BOJ’s monetary policy has changed dramatically since April 2022, for which two developments can be cited. The first is the effect of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the early days of 2022, the global spread of the COVID-19 virus since 2020 was being met with the uptake of vaccinations, and the world economy was beginning to revive. It was this moment when Russia launched its invasion.

This shocked the world, which had come to believe that a war of this nature would not occur after the conclusion of the Cold War. The invasion caused resource prices and wheat, soybean, and other grain prices to soar, greatly impacting Japan as well as such economies as Europe and the United States. Although not as large a rise as in the United States, prices ascended in Japan due to the depreciation of the yen and the increase of resource prices.

The CPI (all items) rose 4.0% year on year in December 2022, and core CPI (all items excluding fresh foods) grew for 16 straight months, climbing 4.0% year on year in the same month. Such high growth has not been seen since the 4.0% recorded in December 1981, when the second oil crisis propelled prices higher.

A Distorted Yield Curve

The second development contributing to the dramatic change in the environment for monetary policy is the unraveling of the BOJ’s yield curve control policy. This is a policy that aims to hold the long-term interest rate (the yield of 10-year Japanese government bonds) and the short-term interest rate within a fixed range. In September 2016, the BOJ modified its quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (monetary easing of a different dimension) to include yield curve control. Hoping to overcome deflation, which was one of the objectives of Abenomics, the BOJ held to its stance of maintaining an expansionary monetary policy until the rate of inflation exceeded 2% in a stable manner.

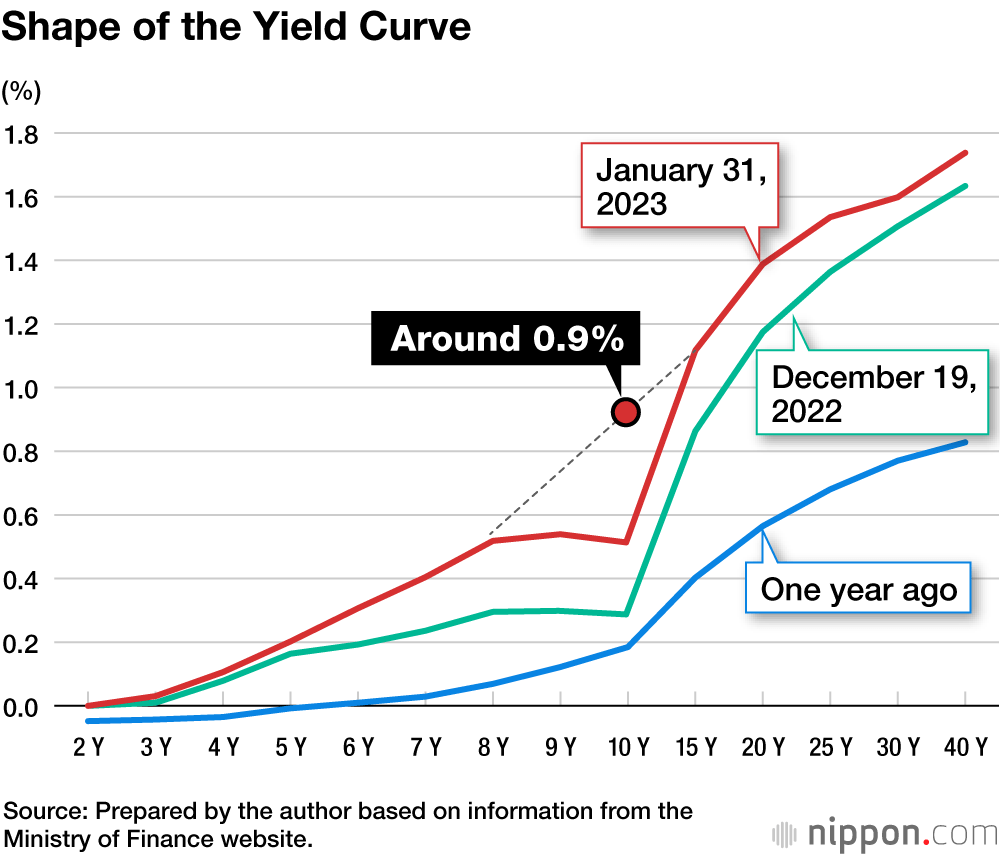

The rate of inflation, however, has already exceeded 2%. As the yen’s sharp depreciation is accompanied by mounting upward pressure of domestic prices, the distortion of the yield curve is becoming pronounced. Interest rates tend to rise as maturities lengthen, meaning that a graph of the yield curve tends to climb to the right. With higher prices placing increased upside pressure on interest rates across the board, the BOJ has purchased large quantities of 10-year JGBs to hold the yield of these bonds below an upper limit of 0.25%. As a result, the yield curve has become distorted, with the yield of JGBs maturing in 8 and 9 years surpassing the yield of those maturing in 10 years.

This distortion is not normal. Should it persist, the market will lose its functionality, and it will become impossible to know the appropriate level of interest rates. For this reason, the BOJ made an abrupt adjustment of its monetary policy at the December 19–20, 2022, Policy Board meeting to change the allowable range of the long-term interest rate (yield on 10-year JGBs) from around 0.25% to 0.5%.

The adjustment the BOJ made is effectively a rate hike, meaning an increase from 0.25% to 0.5% in the upper range of the long-term interest rate. The yield curve, however, remains distorted (see the chart above) as upside pressure on interest rates from rising prices persists. The difficulty for the BOJ is the way it is being driven to continue purchasing large quantities of JGBs to hold the upper range of the long-term interest range below 0.5%.

As a result, the JGBs held by the BOJ reached an all-time high of ¥564 trillion as of the end of December 2022. Further expansion of the bank’s JGB holdings will signal the continuation of monetary easing, magnifying pressure for higher prices and a weaker yen. Rising prices will generate upward pressure for the long-term interest rate. Seeking to curb such pressure through yield curve control will only further distort the yield curve.

To control the long-term interest rate, the BOJ will need to continue its purchases of long-term government paper, which will further augment the BOJ’s JGB holdings. There is no other way to thwart this vicious circle than to normalize monetary policy and to gradually entrust the level of the long-term interest rate to the market mechanism. Such a step, however, will also harbor significant risk for government finances.

The Risk of Exploding Interest Expense

Despite the outstanding balance of JGBs exceeding ¥1 quadrillion, the government is able to issue large quantities of such bonds without having the interest of JGBs rise greatly and without creating fiscal difficulties. This situation is made possible by the BOJ holding the long-term interest rate at a low level through yield curve control.

If the mechanism for determining the long-term interest rate is gradually transferred to the market and if the interest of JGBs rises, the interest expense of JGBs will also increase. The interest expense rising by several trillions of yen could be handled fiscally. However, this expense growing by more than ¥10 trillion would be a different situation in light of the sluggish growth of tax revenues.

A satisfactory outcome would be the BOJ succeeding in normalizing monetary policy and the long-term interest rate converging around 1%. However, if the BOJ fails in its attempt at normalization due to stronger than expected upside pressure on interest rates and if the long-term interest rate surpasses 3%, this would risk creating a fiscal crisis.

Some might argue that, given the risks of normalization, the BOJ should simply continue to control the long-term interest rate. There is, however, no guarantee that the BOJ will be able do so forever. While political forces can temporarily deform the economy (market mechanism), the likelihood is high that the economy will defeat political forces in the end. An unraveling is inevitable.

It is worth bearing in mind that, when the government and the BOJ are viewed as a single entity, the cost of their combined debt will not change regardless of whether the BOJ holds government bonds or not. The cost of debt is presently not materializing since interest rates are close to zero, but once deflation ends, the cost-free financing of budget deficits will no longer be possible, and huge debt service costs will reemerge. As upward pressure on prices strengthens, whether the BOJ will succeed in the heavy responsibility of transforming its monetary policy will depend on the abilities of the new leadership.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Ueda Kazuo, at right, the next BOJ governor, and his predecessor Kuroda Haruhiko, at left, at a symposium held in Sendai, Miyagi, in May 2016. © Kyōdō.)