“Shichifukujin”: Japan’s Seven Gods of Fortune

History Culture Lifestyle Guide to Japan- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The priest Tenkai, founder of the Buddhist temple Tōeizan Kan’eiji in Ueno and onetime political advisor to the shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu, stated that the seven virtues of an ideal statesman were longevity, prosperity, popularity, integrity, dignity, kindness, and magnanimity. It became a widespread belief among Japanese people that these virtues could be bestowed as blessings by the shichifukujin or Seven Gods of Fortune. Along with Ebisu, an ancient Japanese guardian deity, there are Daikokuten, Benzaiten, Bishamonten, Hotei, Fukurokuju and Jurōjin, who all originated from continental Asia.

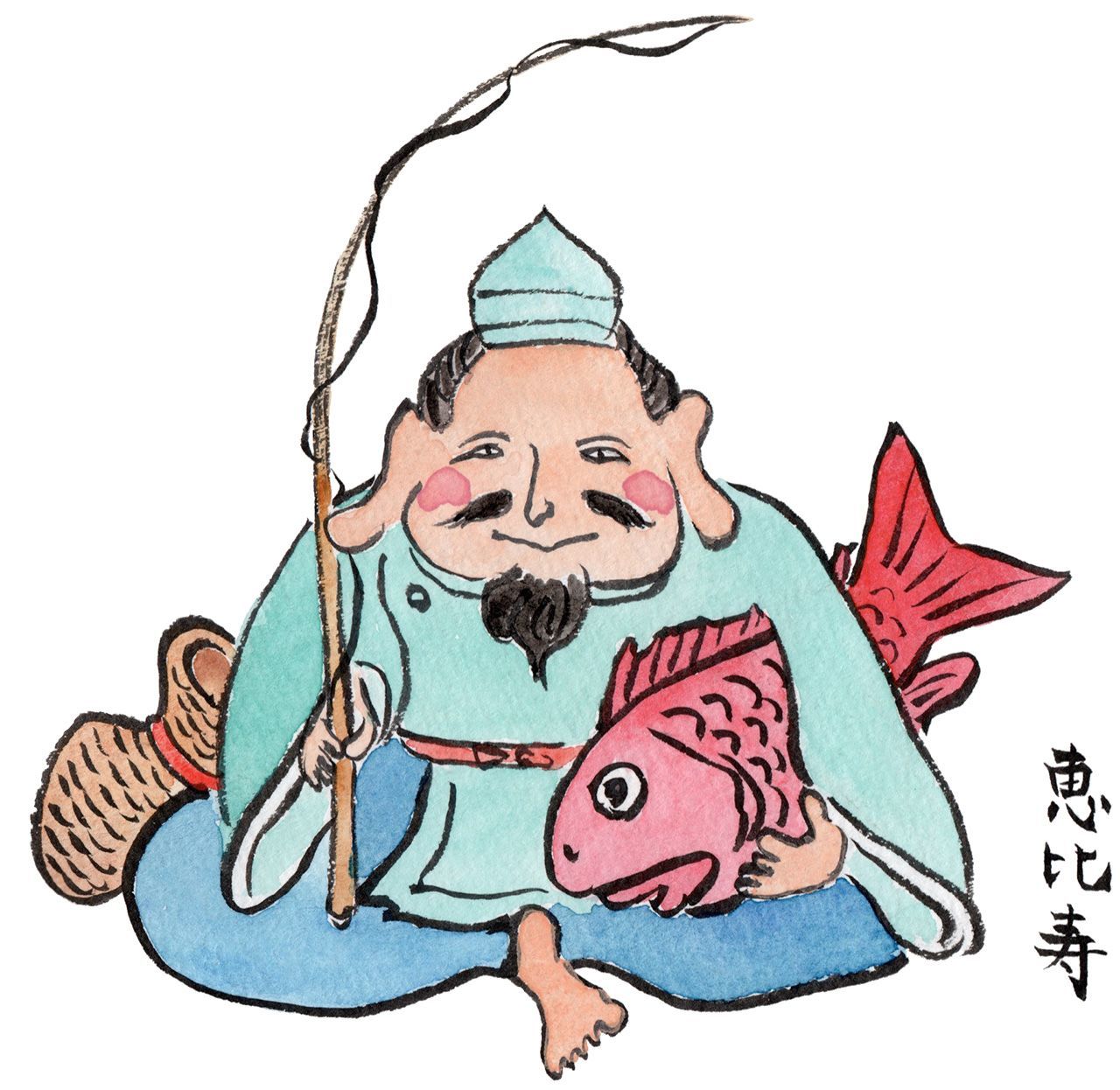

Ebisu (Integrity)

Ebisu has his origins as a child of the god Izanagi and goddess Izanami, the creator deities of Japan. Formerly known as Hiruko, he had an unfortunate start in life as, due to a birth defect, his parents cast him away to sea in a boat of reeds. However, the boat luckily drifted back to shore at a different location, where the child was lovingly raised, eventually becoming a god of good fortune.

Ebisu’s connection with the sea also led to him being regarded as the god of fishermen, hence his carrying of a fishing rod and a large tai, or sea bream. Sea breams are considered lucky in Japan due to the association with the word medetai or “auspicious.”

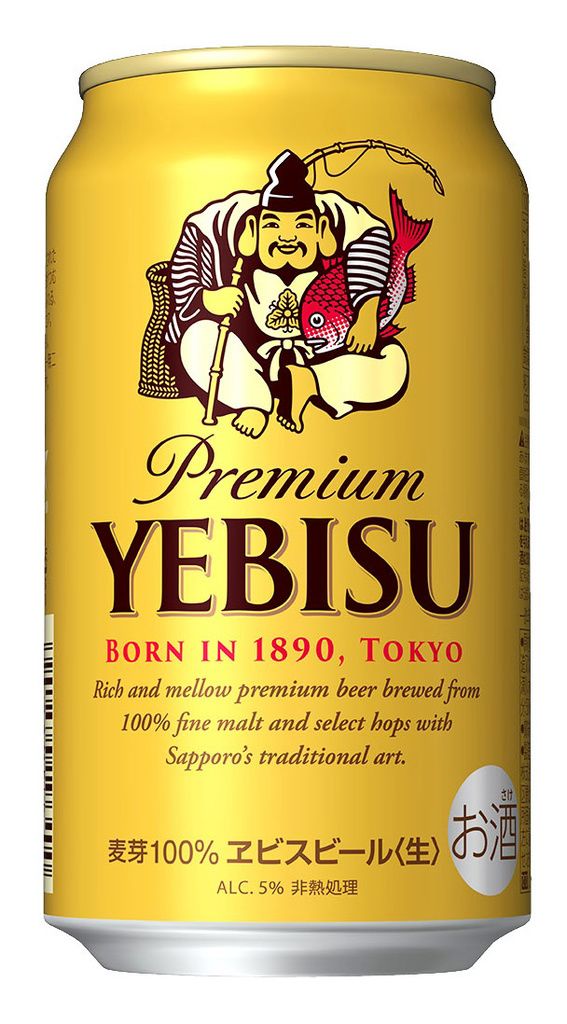

Ebisu is probably the most well-known of the shichifukujin among Japanese people. This is because he is the icon for Yebisu, Sapporo Brewery’s premium brand of beer, which is often seen in supermarkets and convenience stores.

Ebisu Station on Tokyo’s Yamanote Line was originally built in 1901 specifically for loading and unloading beer. The beer and later the district both owe their naming to this lucky god and it seems to have been a good choice as Yebisu Beer has remained popular for more than a century and the area of Ebisu has flourished.

Kansai is noted for festivals each January celebrating Ebisu at locations including Imamiya Ebisu Shrine in Osaka and Nishinomiya Shrine in Nishinomiya, Hyōgo Prefecture. The latter features a race in which the fastest runners become fukuotoko or “lucky men,” and are blessed with good fortune for the year.

Hopefuls dash to become the fukuotoko at Nishinomiya Shrine (© Jiji)

Daikokuten (Prosperity)

Daikokuten, the god of prosperity, holds a golden mallet and sack—the mallet is the magical uchide no kozuchi, which can make anything one desires appear when swung. Daikokuten’s form is based on both the Shintō deity Ōkuninushi-no-Mikoto and the Hindu deity Shiva in his fierce manifestation as Mahākāla, known as the “Great Blackness” or the ultimate destroyer of all things. As the characters for Ōkuni (大国) can also be read daikoku, which is a homonym for “great blackness” in Japanese, that seems to be how this god became associated with the Indian deity.

Benzaiten (Kindness)

Benzaiten is the only goddess among the shichifukujin and is based on the Hindu goddess of water Saraswati. She stands for the virtues of music, eloquence, and wisdom, and is often depicted holding a biwa, a traditional Japanese lute. Although her name was originally written 弁才天 (Benzaiten), her associations with wealth in Japan mean that her name sometimes appears as 弁財天 (Benzaiten), with the center Chinese character changed from 才 (genius) to 財 (fortune/wealth).

There are shrines around Japan known as zeniarai Benten. Benten is the simplified name of Benzaiten and zeniarai means literally “to wash money.” As the name infers, you can wash your money in the spring water found at these shrines, with the hope that it may multiply and bring you wealth. The most well-known spot close to Tokyo to try this is Zeniarai Benzaiten Shrine in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture.

Washing money in the hope of increasing financial fortune. (© Pixta).

Bishamonten (Dignity)

Bishamonten is a warrior god often depicted clad in heroic armor. He was worshiped by warlords during Japan’s Warring States period (1467–1568). Uesugi Kenshin, one of the most powerful daimyō of that period and a skilled military commander, was a fervent follower of Bishamonten and would pray to him before going into battle. Due to his military prowess, some thought that Uesugi was possibly a reincarnation of Bishamonten. However, Bishamonten was not originally a god of warfare. In India, he was regarded as a heavenly king who had the power to bestow treasures. It was only after worship of this deity crossed to China that he became regarded as a warrior god. In his left hand he holds a treasure pagoda or stupa, representing Buddha’s teachings and the riches that can be achieved, and in his right a long lance to ward off evil.

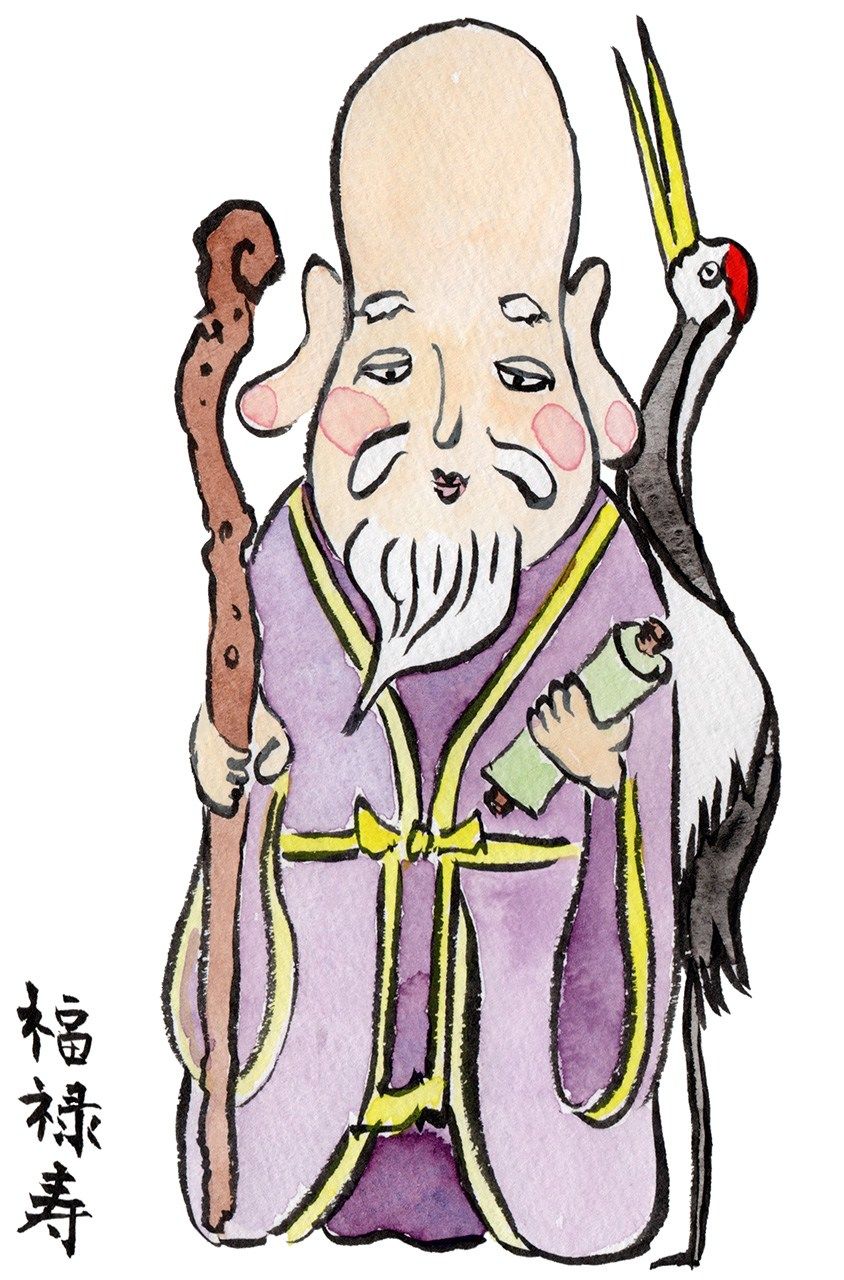

Fukurokuju (Popularity)

In Taoism, this god is considered to be the deification of the nankyokusei or southern pole star. He brings good luck for having children, along with prosperity, health, and longevity. He is often accompanied by a crane, a well-known symbol of longevity. He is sometimes conflated with Jurōjin, or they are said to be twins. One way to tell them apart is to observe which animal is standing with each one.

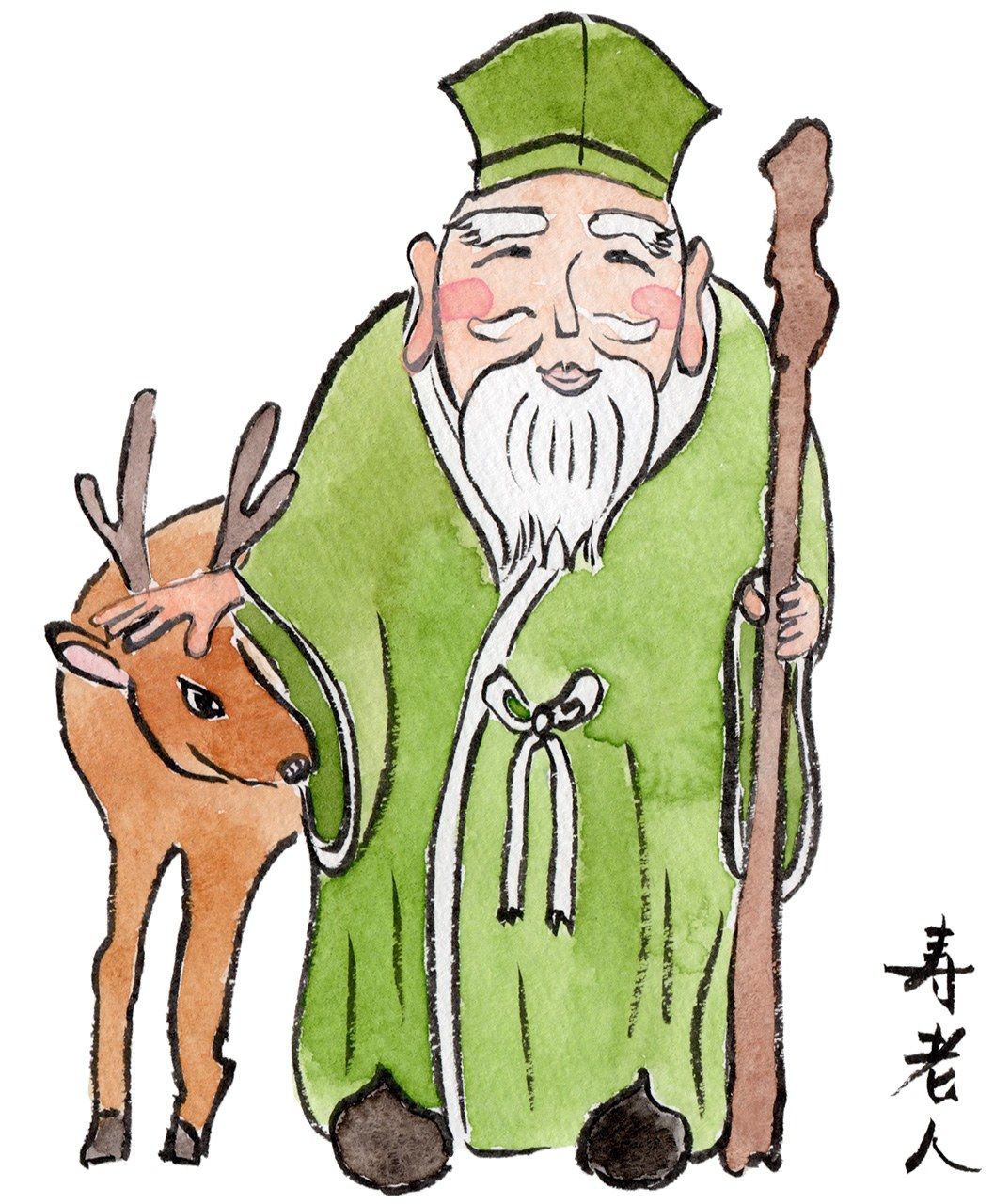

Jurōjin (Longevity)

Similar to Fukurokuju, the deity Jurōjin is regarded in Chinese Taoism as the deification of the nankyokusei, seeing which is said to extend one’s life. He is often regarded as the same deity as Fukurokuju and frequently appears standing with a deer, which is a way to differentiate these two gods. He is believed to bestow longevity and to cure illnesses.

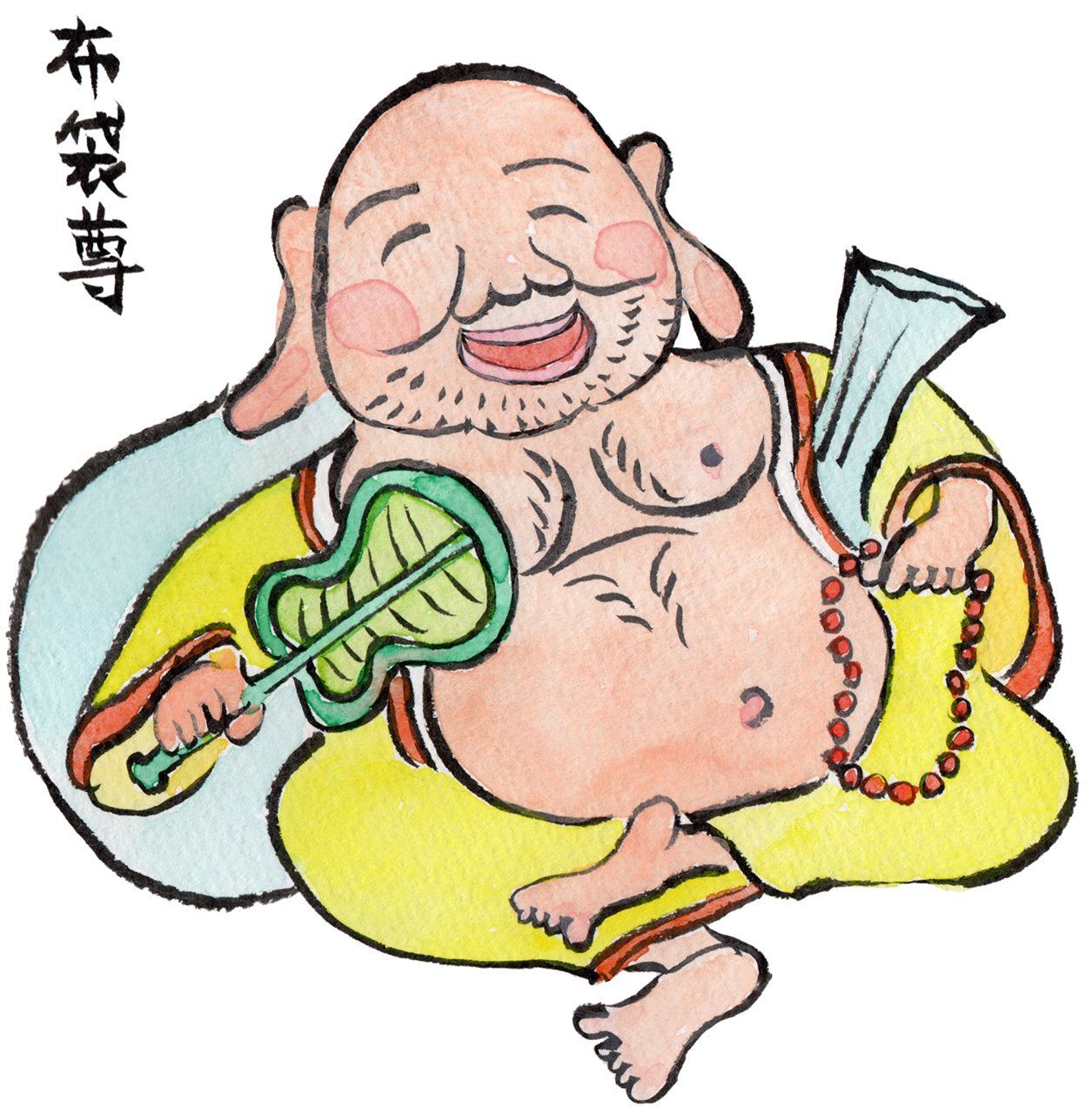

Hotei (Magnanimity)

Hotei is the only one of the shichifukujin who actually existed as a person. He was based on Budai, a Chinese Buddhist monk who lived around the tenth century and is said to have wandered half-naked through towns predicting people’s fortunes. The Chinese characters for his name 布袋 (Hotei) can also be read as nunobukuro, literally “cloth sack”, and he is often shown carrying a large sack, from which he pulls out rice and sweets to give to the poor and to children. The fan that he holds in his right hand represents the authority to grant wishes. He brings happiness in the form of laughter and harmonious marriage.

Shichifukujin Meguri (Lucky God Pilgrimages)

For ordinary people in Edo (now Tokyo), making a shichifukujin meguri, or tour of the shrines where each of the seven gods were enshrined was both a matter of faith and a way to enjoy a little bit of leisure time. These pilgrimages can still be undertaken today. In Tokyo, the most renowned walking courses to visit all seven lucky gods in each of their shrines are Yanaka, thought to be the oldest of these pilgrimages and which takes one through Arakawa, Taitō, and Kita near Ueno; Yamate, a shorter pilgrimage around Meguro Station; and Sumidagawa, which as its name implies, is a pilgrimage that takes one along the Sumida River starting near Tokyo Skytree. There are many more such pilgrimages all across Japan.

Originally, it was considered appropriate to visit the shichifukujin at New Year. A related custom is the placing of a slip of paper with a drawing of a “treasure ship” carrying the seven gods (as seen in this article’s main picture above) under one’s pillow to encourage a lucky “first dream” of the year. In more recent times as part of promotion for tourism, some places advertise these pilgrimages as fun trips and walking courses that can be done all year round. Why not go on one yourself and see what fortune these seven lucky gods can bring you?

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)