Drawing Up the Meiji Constitution: Popular Rights and Political Wrangling

History Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Early Calls for a Constitution

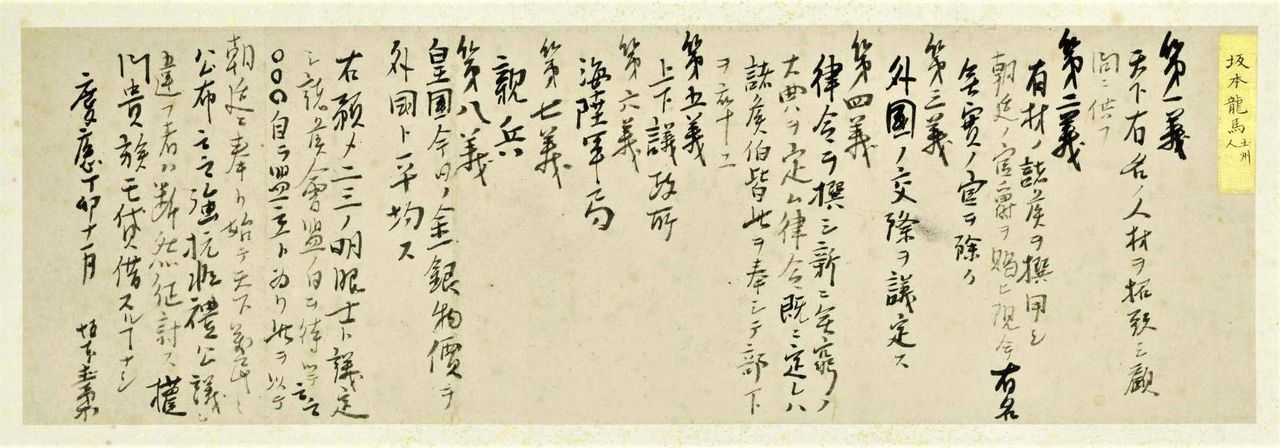

In the 1860s, shortly before the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate, research overseas by people like Nishi Amane and the influence of foreign books set off discussion of Western constitutions and constitutional governments in Japan. Sakamoto Ryōma’s influential eight-point plan, in which he outlined his vision of a new post-shogunate government, called for the establishment of upper and lower houses of parliament, as well as a new constitution.

Sakamoto Ryōma’s handwritten version of his eight-point proposal for a new government. (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

The new Meiji government was still fighting the Boshin Civil War against shogunate forces in June 1868 when it published the Seitaisho, a document that vested power in the Dajōkan, or Grand Council of State. This consisted of seven departments overseeing different areas, and took a form based on the separation of judicial, executive, and legislative powers seen in the US Constitution.

The government secured absolute power in 1871 by abolishing the feudal domains and establishing prefectures in their place. It then divided the Dajōkan into three councils with subordinate ministries and offices. Of these, the Central Council had supreme power, and was equivalent to today’s cabinet. It consisted of the dajō daijin, or grand minister, ministers of the left and right, and a number of councillors. The Council of the Left was an advisory body on forming legislation made up of government-selected members that the Central Council consulted for expert advice when preparing important laws. The heads and vice-heads of the ministries and offices met in the Council of the Right to discuss political affairs.

In 1874, eight councillors supporting a failed proposal to launch a military expedition to Korea left the government. These men, including Itagaki Taisuke, formed a society named Aikoku Kōtō (Public Party of Patriots) and presented a petition to the government, calling for the establishment of a national assembly.

Itagaki returned to his native Tosa (by then Kōchi Prefecture), where he founded the political association Risshisha (Self-Help Society). Continuing to advocate the need for a national assembly, he promoted a movement for popular rights. After other local associations sprang up, in 1875 Itagaki concentrated their power in a new group called Aikokusha (Society of Patriots) in Osaka.

Home Minister Ōkubo Toshimichi was effectively the leader of Japan under the Dajōkan system. Rattled by the rise of the popular rights movement, he arranged a meeting in Osaka with Itagaki and Kido Takayoshi, a major political figure from the former Chōshū province (by now Yamaguchi Prefecture) who had resigned in protest against a punitive expedition to Taiwan.

At this meeting, Ōkubo agreed to gradually introduce parliamentary politics based on a constitution. In April 1875, an imperial edict was issued for establishing a constitutional government, and new bodies were formed: the Genrōin, which was a kind of nominated senate; the Daishin’in, which acted as a supreme court; and an assembly of prefectural leaders. As a body for legislative deliberation, the Genrōin began work on Japan’s first government-written constitutional draft in 1876.

At the first meeting of prefectural leaders, with Kido acting as chairman, there was a heated debate over whether local assemblies should be elected or appointed by the government; in the end, it was decided that they should be appointed.

A Promised Assembly

Repeated samurai uprisings flared up in 1876, which were suppressed by the government. The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 headed by Saigō Takamori was a more serious threat, but this was also put down. The difficulty of overcoming the government by force gave fresh impetus to efforts to bring it down through words and inaugurate a national assembly via the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement.

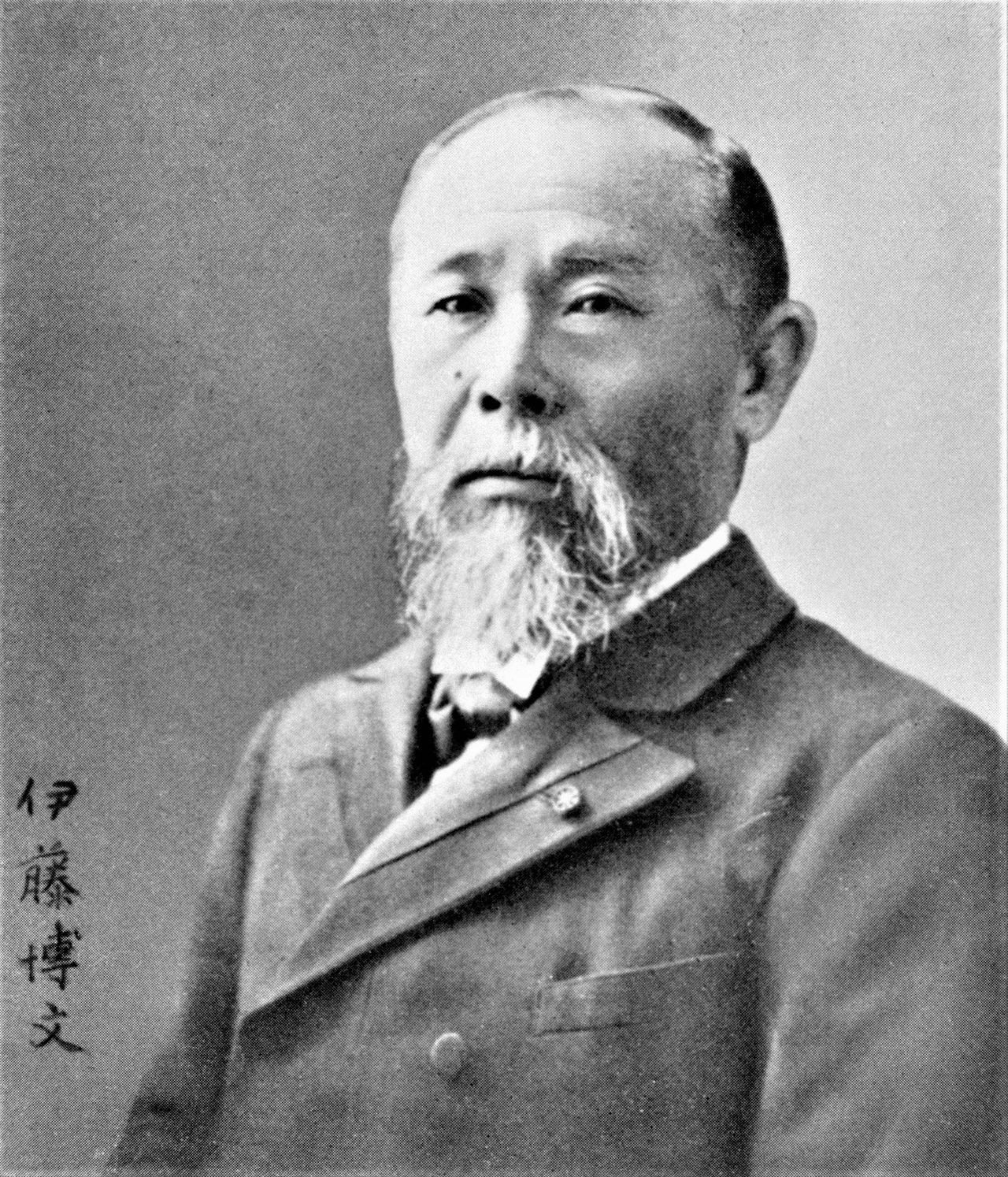

Ōkubo was assassinated by discontented samurai in 1878, and in his place Ōkuma Shigenobu originally of Bizen province (Saga Prefecture), and Itō Hirobumi of Chōshū rose to influence. Ōkuma showed sympathy to the movement for popular rights, and insisted on the rapid opening of a national assembly.

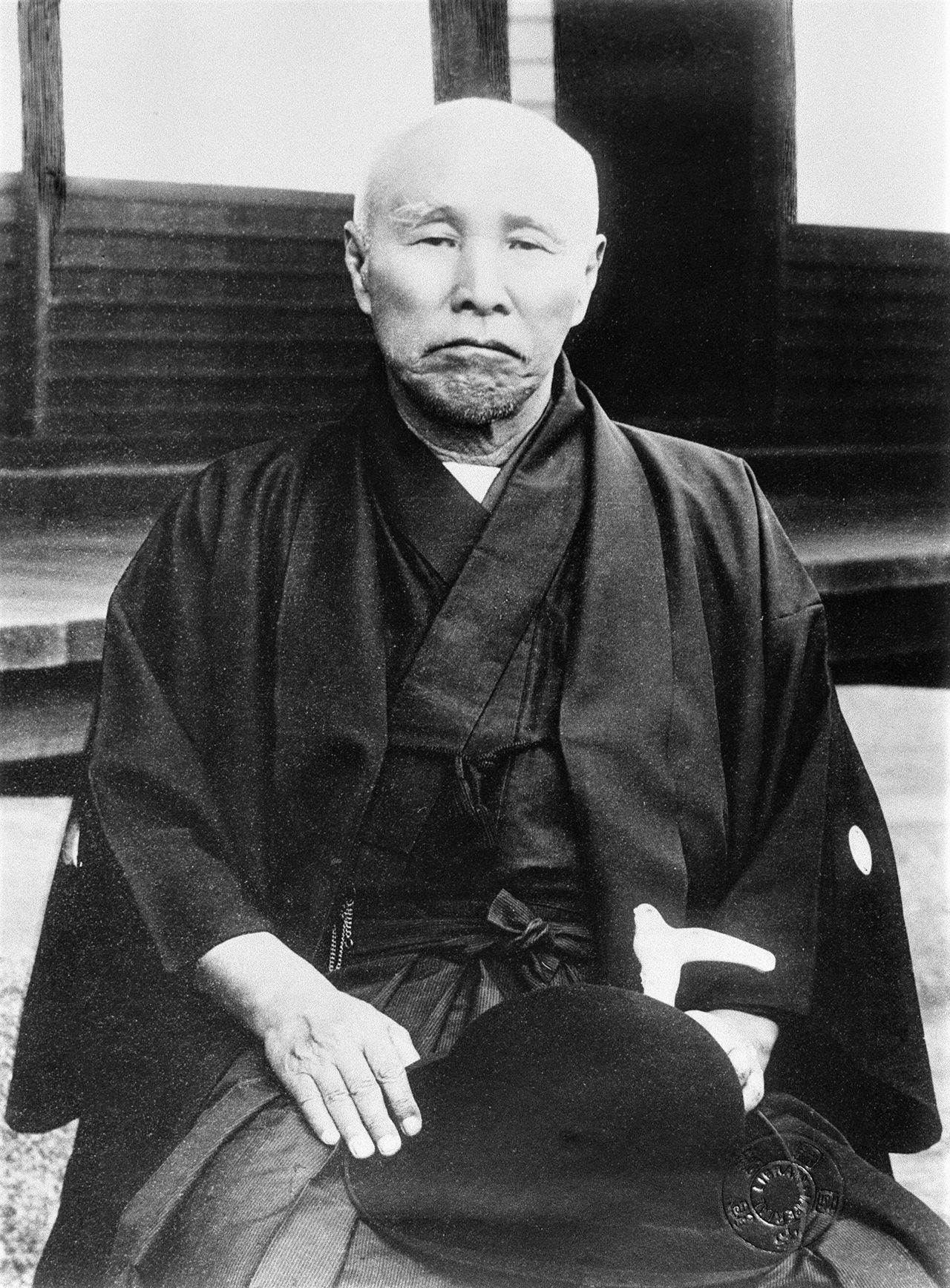

Politician Ōkuma Shigenobu favored a British-style constitution. (© Jiji)

In March 1881, Ōkuma submitted a written opinion to Minister of the Left Prince Arisugawa, saying that a constitution should be created within the year and promulgated in 1882, and that there should then be a national assembly and British-style parliamentary democracy.

When the conservative Iwakura Tomomi, who was minister of the right, showed his distaste for this suggestion, Itō joined forces with him, and the two approached Kuroda Kiyotaka, the director of the Hokkaidō Colonization Office. Kuroda was in a tight corner, under fire by supporters of popular rights for trying to sell the office’s assets and projects at a nominal price to Godai Tomoatsu, who like him was from the former Satsuma province (now Kagoshima Prefecture). Itō said that Ōkuma was working with the popular rights movement to undermine Kuroda, and they entered into an alliance.

The Sat-Chō (Satsuma and Chōshu) faction made its decisive move on October 11, 1881, opening a meeting with Emperor Meiji in attendance, and dismissing Ōkuma from his position as councillor for his alleged involvement in attacks on the government. At the same time, it had an imperial decree issued promising the people a national assembly in 1890.

This historic power seizure became known as the Political Crisis of Meiji 14 (1881). The exit of Ōkuma and his followers left the Sat-Chō faction in total control, with Itō at its head.

Itō Hirobumi was Japan’s most powerful politician from 1881 onward. (© Jiji)

Private Drafts

Around this time, the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement was at an unprecedented peak of activity, with demands for a constitution accompanied by draft proposals relayed to the public via newspapers and magazines.

These private draft constitutions came from organizations like Kōjunsha (including Fukuzawa Yukichi) and Risshisha, as well as individuals including Ueki Emori and Chiba Takusaburō.

Ueki’s French-influenced constitution draft was particularly radical, calling for a unicameral parliament, and incorporating rights to resistance and revolution in the case of a bad ruler or state. However, most of the private draft constitutions were in the British style, with a constitutional monarchy and two legislative bodies.

Meanwhile, the Genrōin completed a government draft in 1880, but this was shelved due to opposition from Iwakura and other conservatives and from the imperial court. The power within the government at that time lay with those who felt a constitution was premature or that Japan was suited to direct imperial rule. Itō, however, envisioned the same constitutional monarchy and bicameral system as his rival Ōkuma.

Maintaining Imperial Power

With its promise of a national assembly by 1890, the government needed to produce a constitution as the basis for a constitutional system. Itō traveled to Europe in 1882 for a survey that lasted more than one year, taking in many countries, including Germany, Austria, Britain, Russia, France, and Italy. He spoke with scholars like Rudolf von Gneist, Albert Mosse, and Lorenz von Stein, as well as the German leader Otto von Bismarck and the British politician Lord Granville.

As a result, he decided that Japan was most suited to a Prusso-German-style constitution, which maintained strong imperial power.

After returning to Japan, in 1884 Itō established the Office for the Investigation of Institutions, which was a body for researching and preparing necessary legislation and systems for constitutional government. Headed by Itō, its other main members were Inoue Kowashi, Itō Miyoji, and Kaneko Kentarō. They worked together to decide matters regarding appointment of officials, regional administration, and the cabinet, as well as drawing up the Peerage Act.

This law expanded the peerage, previously consisting of former daimyō and kuge (court nobles), by adding members for their contributions to the Meiji Restoration or who were high officials in the government. It was motivated by Itō’s wish to establish a House of Peers to stand alongside a popularly elected House of Representatives.

Completion and Promulgation

With the elements of a constitutional system in place, from 1886 Itō and the others began to draft a constitution. They examined several drafts at the Azumaya ryokan in Yokohama’s Kanazawa district, where the German legal scholar Hermann Roesler also came to offer advice.

One day, however, a bag containing draft constitutions disappeared from the room, causing shock and consternation. It would have been a major issue if a popular rights group had had an early look at the content. As it turned out, the thief was only interested in valuables, throwing the bag and its apparently worthless papers away in a nearby field.

The incident was enough to prompt a move to Itō’s villa on the island of Natsushima just offshore from Kanazawa. Here the four men were able to debate as much as they liked, sometimes escalating to heated argument. They eventually produced the Natsushima Draft Constitution in August 1887.

After repeated deliberation in the newly established Privy Council, an advisory body to Emperor Meiji, the completed Constitution of the Empire of Japan, now commonly known as the Meiji Constitution, was promulgated on February 11, 1889.

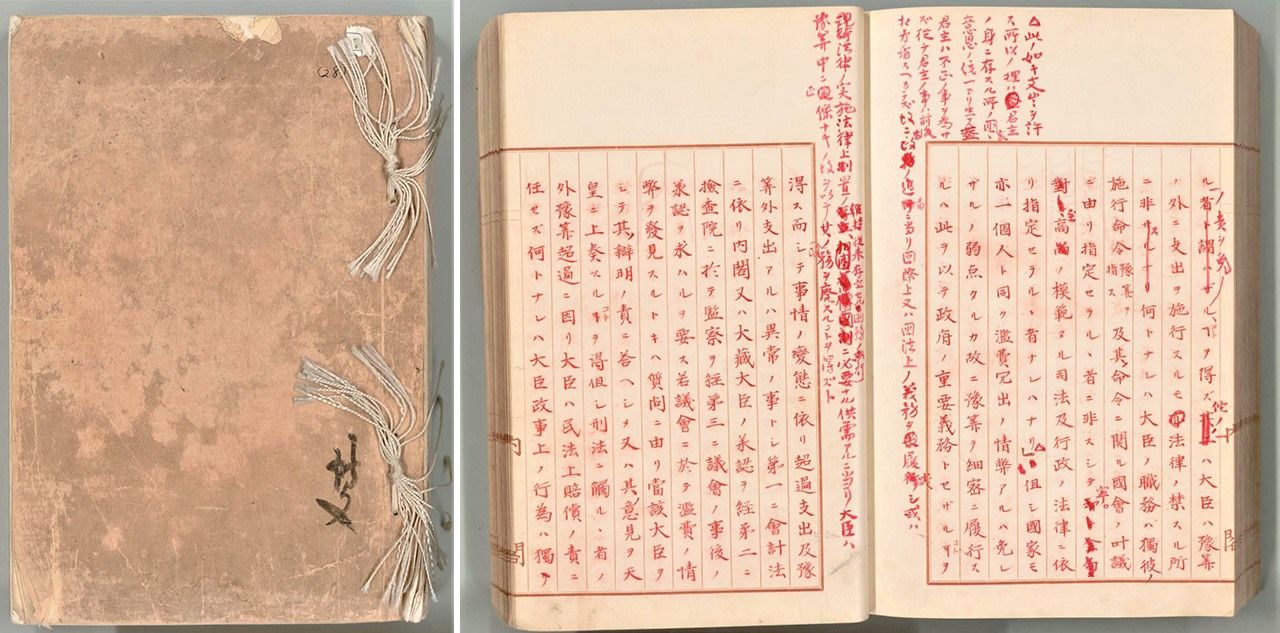

After some polishing, the Natsushima Draft Constitution was ultimately completed in March 1888. It is signed on the cover by Itō Hirobumi, who is said to have penciled notes on required editing during Privy Council meetings. (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

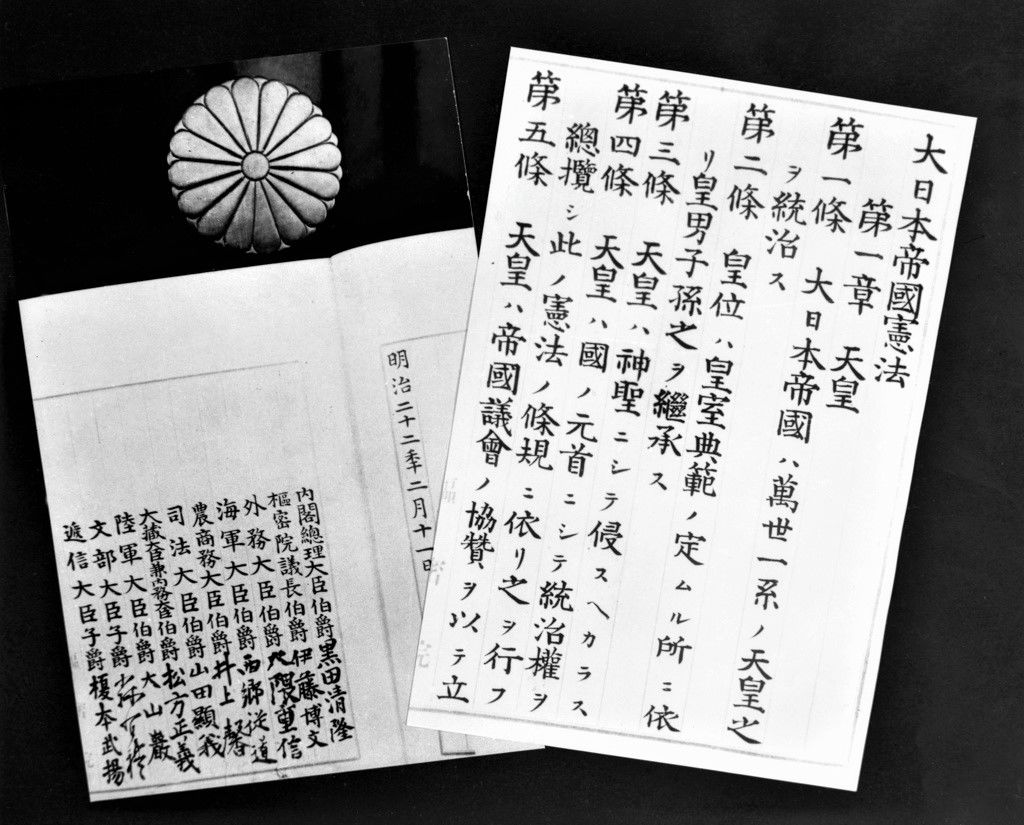

A copy of the original Meiji Constitution. (© Kyōdō)

Coming in the form of a constitution bestowed by the emperor upon the people, the document was based around imperial sovereign power (tennō taiken). The emperor could declare war, make peace, enter into treaties, and appoint and dismiss government officials, and was also the commander of both the army and navy. The first article of the Constitution states that “The Empire of Japan shall be reigned over and governed by a line of Emperors unbroken for ages eternal,” while the third says that “The Emperor is sacred and inviolable.”

This has led to the belief that the Meiji Constitution was an undemocratic affirmation of dictatorial power for the emperor. This is not true, however, as I will explore in a subsequent article.

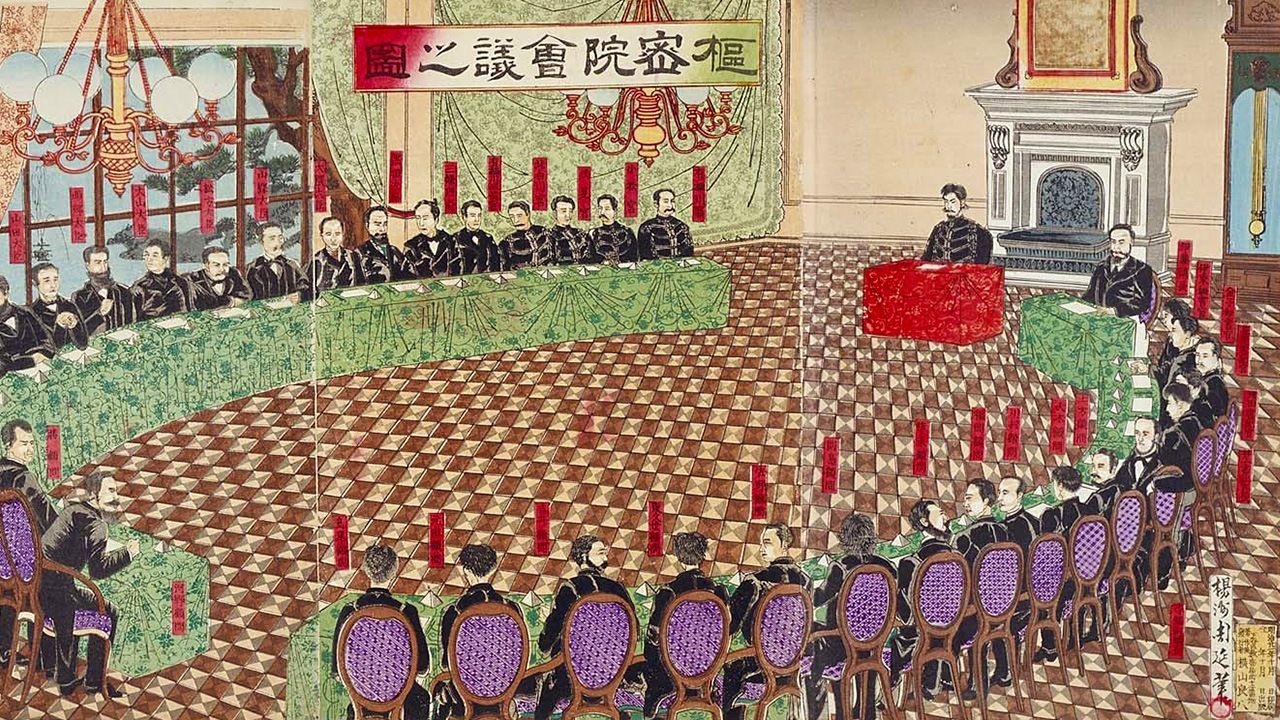

(Originally published in Japanese on March 1, 2023. Banner image: The Privy Council, founded in 1888 to discuss the Constitution. It consisted of Meiji politicians and high-ranking bureaucrats and the emperor attended its meetings. Sūmitsuin kaigi no zu (A Meeting of the Privy Council) by Yōshū Chikanobu. Courtesy the National Diet Library.)