Confronting the Years: A Photographer’s Tour of Japan’s Hyper-Aging Society

Super-Ager Food Historian Nagayama Hisao: Spreading the Gospel of Longevity Through Japanese Cuisine

Food and Drink Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

“I’ve got years ahead of me still. Gotta hang on at least until I’m a hundred, another nine years. But I could live to a hundred and twenty—it’s not a pipe dream!”

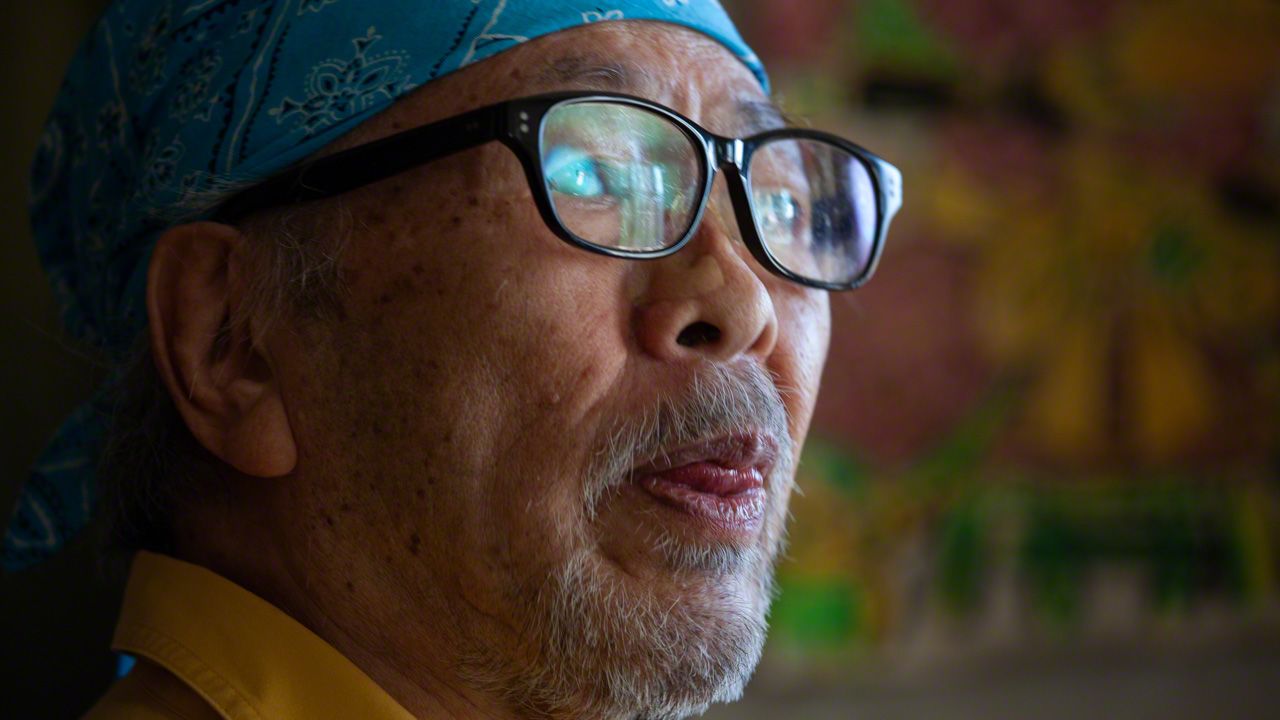

Food-culture historian Nagayama Hisao, age 91, chuckles merrily and continues chopping carrots for his model longevity meal. His back is straight, his movements quick and precise, his speech punctuated with hearty laughter. “When you laugh,” he explains, “you activate your natural killer cells and give your immunity a big boost. Laughter is the best medicine. Haha!” His enthusiasm is overwhelming. Will I be able to convey such joie de vivre at his age, 20 years hence?

Dressed in bright yellow, Nagayama Hisao greets the interviewer warmly outside his cheerful yellow house. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

A taste of homemade dashi stock elicits a beatific grin from Nagayama. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Picking Up Speed

“My work began to pick up when I was around seventy, and I got my big break at age eighty-five,” Nagayama says. “It’s never too late to learn something new.” There is no doubting the strength of his conviction. I ask him if he ever thinks about death.

“I haven’t got time to worry about dying,” he replies. “I think death is like being released from the earth’s gravity and floating up weightless to another world.” It’s not hard to imagine Nagayama gathering speed right up until he dies (unlike the vast majority of us) and then lifting off like an airplane.

We human beings developed our oversized brains when we began walking on two legs, resisting the pull of gravity. Perhaps, indeed, death is the final release from those physical bonds.

In any case, Nagayama is one busy super-ager. He is forever receiving requests to appear on TV or YouTube, talk on the radio, and write for magazines. TV work keeps him especially sharp, he says, with its insistence on quick answers. Nagayama advocates a life of unending curiosity and “running about,” and he definitely practices what he preaches.

He is quick to pick up on commercial opportunities as well. His book Murasaki Shikibu: Gohan de wakagaeru (Murasaki Shikibu: Turning Back the Years with Diet) came out in December 2023, just before NHK, Japan’s national Broadcaster, began airing its yearlong historical drama series on the author of the eleventh-century Tale of Genji, and he is collaborating with NHK on another tie-in. With his undiminished vigor, Nagayama is a walking advertisement for his own longevity diet, and the media cannot get enough of him.

Roots in the Family Business

Nagayama was born in 1932 in Naramachi, Fukushima Prefecture. His family ran a business making kōji, steamed rice treated with a special mold—Aspergillus oryzae—to facilitate fermentation. They did a brisk business back then, when many households used kōji to brew their own miso and amazake (a sweet, low-alcohol sake). As a child, Nagayama would help out in the kōji chamber, steaming the rice and sprinkling it with Aspergillus spores.

Nagayama believes his formative experience handling kōji inspired and enriched his longevity studies. Kōji is still used to produce the soy sauce, miso, and sake that are so basic to the Japanese diet. Nagayama regards fermentation, including pickling, as fundamental to washoku (Japanese cuisine) and a key to the vaunted health and longevity of the Japanese people.

That brings us to the story of Nagayama’s treasured 91-year-old umeboshi (pickled plums).

As a young man, Nagayama left home to study at a regional university, but he contracted tuberculosis and was obliged to recuperate at home. During his convalescence, he plunged into the study of medicine, food, and nutrition while writing and submitting short stories and manga for publication. After winning a number of prizes for his submissions, he moved to Tokyo at age 25, determined to make a living as a cartoonist.

During those first few weeks of stress and uncertainty, he drew great comfort from a care package his mother sent him. At the very bottom of the wicker basket he found a container of umeboshi from the batch of salt-preserved pickled plums his mother had made when he was born, in accordance with local custom. Having long prescribed umeboshi as a prophylactic against infectious disease, his mother had shipped some to Tokyo out of maternal concern for her son’s health in a new environment filled with unknown pathogens.

The remaining umeboshi are among Nagayama’s most prized possessions. With their antibacterial properties, traditionally made umeboshi can keep almost indefinitely. Frosted with salt crystals, Nagayama’s 91-year-old pickled plums continue to safeguard his health.

Nagayama’s 91-year-old umeboshi, made when he was born. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Garlic pickled for one month in miso with rice kōji, another of Nagayama’s recipes for long life. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Trials and Triumphs of a Late Bloomer

In the middle of Nagayama’s garden stands a smiling rough-hewn stone figure holding a rice paddle. It represents the god of the rice fields, Ta no Kami, known in Kagoshima (where such images are common) as Tanokansā. The figure had called out to him as he was walking past an antique shop in Kyoto, and he just knew he had to have it. “I got the feeling it was telling me to spread the word about the importance of diet. And the more I did, the more my face began to resemble Tanokansā’s. It’s really become my guardian deity,” he says.

Stone carving of Tanokansā (Ta no Kami, or god of the rice fields) in Nagayama’s garden. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

At age 91, Nagayama is in high demand as a diet and longevity guru, but the road to success was not an easy one. His wife took ill and passed away when their child was still an infant, and Nagayama was forced to go from publisher to publisher peddling his wares with his baby strapped to his back. For decades he struggled to earn a comfortable living. In his spare time, he immersed himself in historical studies, reconstructing native Japanese cuisine from ancient times to the Meiji era (1868–1912). He traveled to famous villages around Japan to study their secrets of longevity and learned that their inhabitants’ long lives were the product of local culinary traditions, each nurtured by that region’s climate and geography.

It was not until Nagayama was 70 years old that the media and the public began to take notice of his work. That was when he published a book on fermented soybeans, riding the wave of a nattō boom. In 2013, UNESCO designated washoku as an intangible cultural heritage, fueling a new surge of interest around the world. But perhaps the biggest breakthrough for Nagayama came in 2019, when he received a Commissioner for Cultural Affairs Award for his research on the history of Japanese food culture. His star has been rising ever since.

Simplicity, Variety, Seasonality

Nagayama’s basic approach to Japanese cuisine is simplicity itself: Don’t overthink or overelaborate, just bring out the natural goodness of the ingredients. Seasonality is also important aspect of cooking in Japan, where the changing seasons have long figured prominently in culture and daily life. Each fruit and vegetable has its own season, or shun, and the shun has three separate phases: hashiri, or first harvest; sakari, or peak; and nagori, or tail end. It is important to pay close attention to these phases when selecting and preparing ingredients. As Nagayama sees it, this essential aspect of washoku is another key to longevity.

In addition, Nagayama has identified eight “longevity foods”: vegetables, dried legumes, fish, chicken, sesame, garlic, umeboshi, and konbu (kelp). All of these healthy ingredients are simmered together in a delicious miso-seasoned stew that Nagayama calls hyakusai nabe (roughly, centenarians’ pot-au-feu).

Nagayama, a talented cartoonist, displays a colorful illustration of hyakusai nabe, a simmered dish incorporating a variety of longevity foods. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

The ingredients of hyakusai nabe (clockwise from top): carrots, daikon radish, konbu, long onions, garlic, yellow onions, shiitake mushrooms , chicken, miso, and katsuo bushi (bonito flakes). (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Nagayama serves up his hyakusai nabe, a miso-seasoned stew of vegetables and chicken. The breast meat of chicken is rich in carnosine, an antioxidant that can slow down the aging process. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

People typically consume three meals a day, and the nutrients in our daily fare are what build and maintain our bones, teeth, muscles, and organs. It only follows that diet can impact our health and longevity. On the basis of his studies, Nagayama has concluded that one of the keys to a long and healthy life is the traditional Japanese rule of thumb for main meals, ichijū sansai (one soup and three dishes.) What this means is that every dinner should include a soup and at least three other dishes (in addition to rice and pickles.)

Eating a variety of dishes at each meal is one of the keys to longevity, according to Nagayama. The rice at left is mixed with carrots and flavored with butter and perilla oil. It is flanked on the right by Nagayama’s miso-pickled garlic. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Appreciation Is the Key

But there is more to healthy eating than the food. Nagayama places great emphasis on mindful eating, as epitomized by the mealtime mantras itadakimasu and gochisō-sama deshita.

“The meals we eat each day aren’t produced by our own efforts alone,” he says. “We owe that bounty first of all to the energy that comes from the sun and the natural environment. It’s important to express your gratitude to those forces by putting your palms together and saying itadakimasu before you dig in. You should also take time to observe and appreciate the food you’re eating. Imagine the energy concentrated in that morsel entering your body and blossoming inside you. That will enrich every meal.”

At the end of a meal, we put our palms together again and say gochisō-sama deshita to convey our gratitude to whoever prepared or provided the meal. “The ‘chisō’ part of the phrase is written with kanji meaning ‘to gallop about,’ conveying the trouble someone has taken to prepare the food,” Nagayama says. “It’s important to show our appreciation for those efforts.”

Nagano stresses appreciative, mindful eating, as expressed in the phrase itadakimasu, typically uttered at the start of a meal. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Nagayama takes a moment to admire a piece of broccoli, noting its resemblance to a large tree. Mindful eating makes for more delicious and healthful meals. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Transmitting the Spirit of the Rice Ball

As a student and apostle of washoku, Nagayama is deeply concerned about recent trends in domestic food production and consumption. “Japan is much too dependent on foreign imports for food, fertilizer, livestock feed, and so forth. Over the past fifty years, imports have become a huge part of the typical Japanese diet. As a result, domestic production has declined and cultivated land has degraded, so it’s necessary to use more and more fertilizer, which leads to a vicious circle. Our worst fears of environmental degradation threatening the survival of the human race are becoming a reality.”

Between jobs, Nagayama likes to recharge by practicing kendō. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Nagayama attaches great significance to the humble but increasingly popular Japanese rice ball as the embodiment of the spirit of washoku. Now widely known as onigiri overseas, they are often referred to as omusubi in Japan. Nagayama prefers the latter term, with its implicit sense of two hands coming together.

“The reason omusubi taste so good is that they’re imbued with the soul of the person who put their hands together to form them. These rice balls are enjoying quite a boom overseas, where they’re known as onigiri. I think the next challenge for the Japanese is to transmit the spirit of omusubi.”

Consumption of onigiri, a.k.a. omusubi, is booming worldwide. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Nagayama, who once dreamed of earning a living as a manga artist, uses whimsical cartoons to help spread the gospel of washoku. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

In one of his inimitable cartoons, Nagayama portrays himself as Hanasaka Jiisan of the Japanese folktale “The Old Man Who Made Trees Blossom,” helping longevity bloom worldwide.

At age 91, Nagayama has a new ambition: to spread the word about washoku and longevity far and wide—not just in Japan but all around the world.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Food-culture historian Nagayama Hisao, age 91. © Ōnishi Naruaki.)