Manga Media and Content in Postwar Japan

“Garo”: The Experimental Magazine That Took Japan’s Manga to a New Artistic Level

Culture Society Entertainment Art Manga- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Passionate About Manga

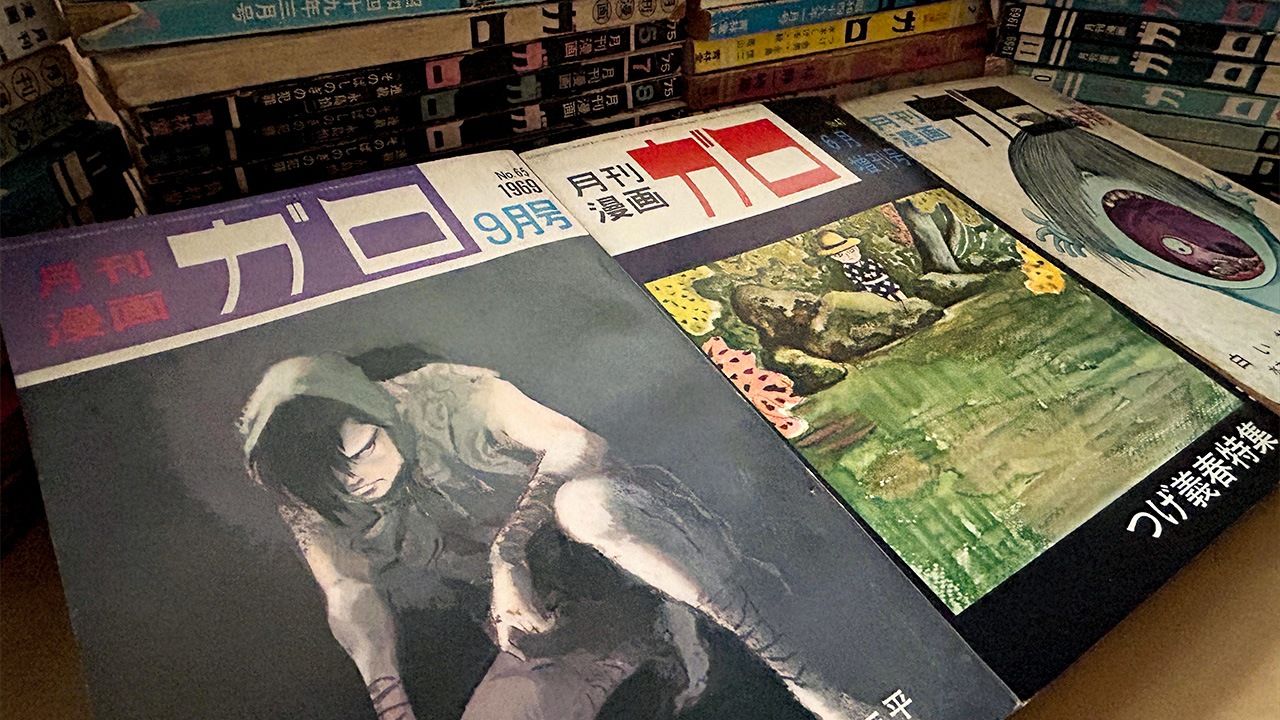

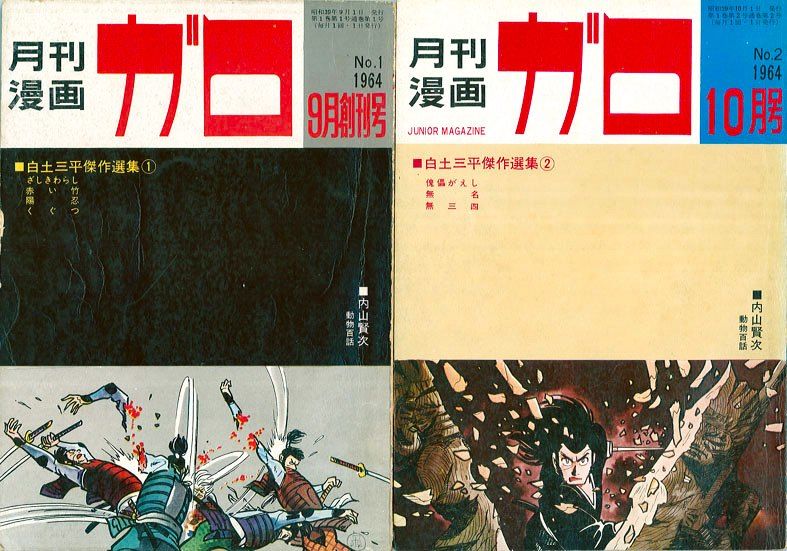

The monthly manga magazine Garo was launched in July 1964, while Japan was swept up in the excitement of rapid economic growth and anticipation of the Tokyo Olympics to be held later that year. Nagai Katsuichi, a legendary editor of numerous hit manga for rental services, conceived of the magazine while in his sickbed with tuberculosis, while Shirato Sanpei, who had caused a splash with his historical manga Ninja Bugeichō: The Legend of Kagemaru, provided full cooperation with funding and key editorial decisions. The aim was to provide a venue for Shirato to publish his next long work, as well as for manga creators faced with diminished opportunities as the rental market stagnated.

The first edition opened with four stories by Shirato and also featured one by the yōkai master Mizuki Shigeru.

Nagai later commented, looking back on this period.

“I was passionate about putting out a manga monthly. I wanted my favorite mangaka to put their hearts into creating whatever they wished to in this magazine. Thinking back on it now, it was practically the first time that I genuinely wanted to publish great manga.”

The first (left) and second editions of Garo. (© Nakano Haruyuki)

At Shirato’s suggestion, the magazine awarded a monthly prize for new creators, aiming to discover new talent in narrative-based “story manga” and the serious gekiga comic style. This was an unusual initiative among manga magazines, demonstrating the Garo editorial goal of publishing manga for a new era, emphasizing originality and individuality.

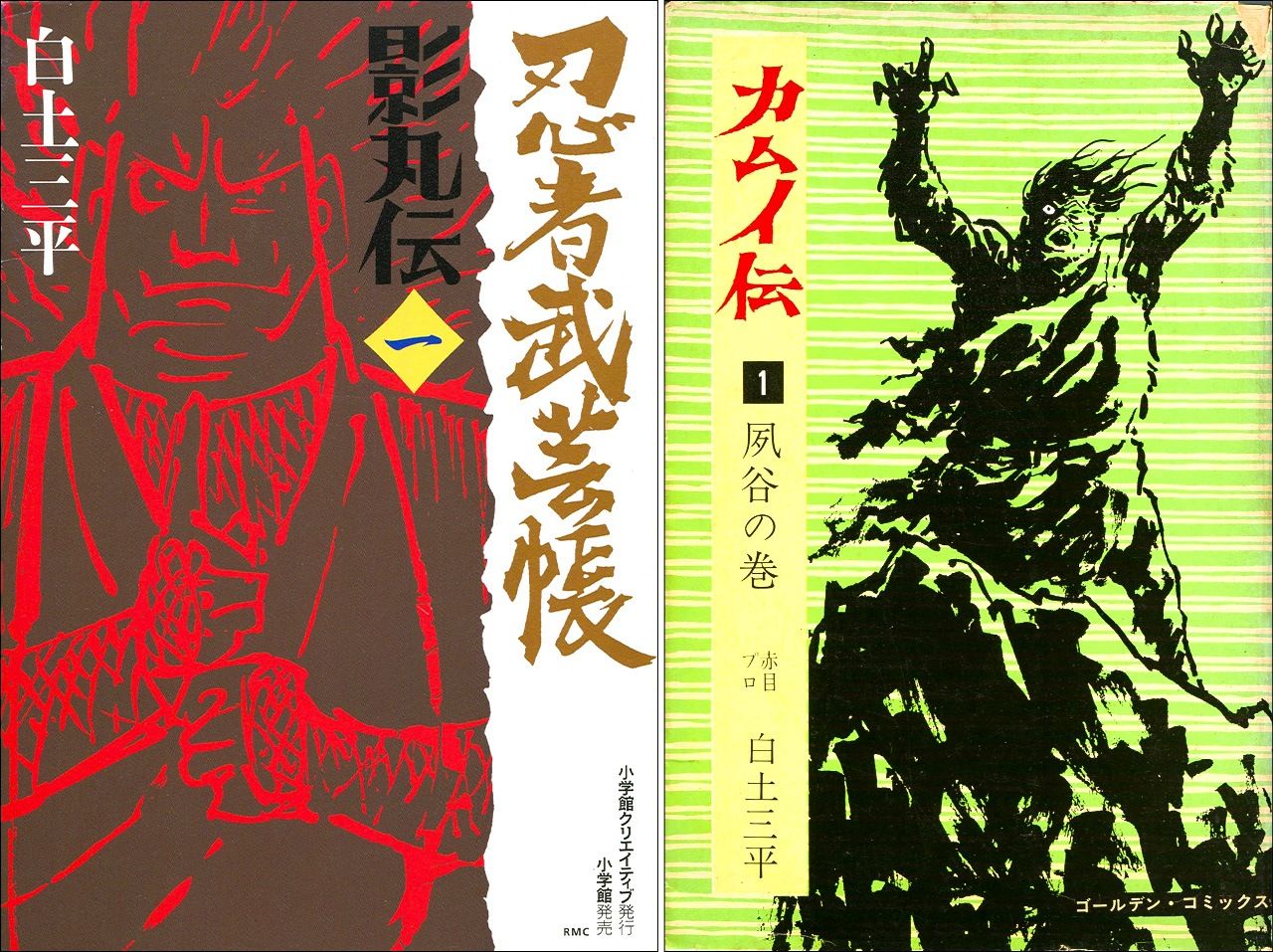

Epic History

Shirato’s new series The Legend of Kamui began in the December 1964 edition. It is set in the early Edo period (1603–1868) in the fictional domain of Hioki, and centers on three main characters: Kamui, a ninja outcast; Ryūnoshin, who left his clan seeking to avenge his family’s eradication; and the farmer Shōsuke. However, the sprawling historical narrative brings together more than 100 characters, and Shirato published over 100 pages in each issue.

The Legend of Kagemaru, the earlier collaboration by Nagai and Shirato, was set toward the end of the Warring States period (1467–1568). In this story, the ninja Kagemaru opposed Oda Nobunaga, who was close to unifying the country under his power. The manga portrays a tumultuous time when many were driven by vengeance.

Ninja Bugeichō: The Legend of Kagemaru (left) and The Legend of Kamui. (© Nakano Haruyuki)

Both works depict social structures and human suffering through characters struggling within the class system. They were described as “historical materialism manga” and won the hearts of young people in a period when student movements were making headlines. The philosopher and historian Tsurumi Shunsuke was among the intellectuals who lauded these works as a kind of ideological movement.

A Manga Outsider

“Please contact me, Tsuge Yoshiharu.”

This sentence appeared in the April 1965 issue of Garo, as Shirato reached out to Tsuge, recognizing his talent as a manga creator.

Tsuge had been fully active in the manga industry since 1955, working in various genres for the rental market. In 1958, he started creating for the major magazines, but found the editors’ demands hard to bear, and returned to rental manga. When the message to him was published in Garo, he is said to have been facing a quandary: his inability to write the manga that he truly wanted to.

After he met Nagai, who asked him to write something for Garo, Tsuge started contributing short works. The Phony Warrior appeared in the August 1965 issue. This was followed by works in 1966 including The Swamp and Chirpy, where he established his own style, influenced by the I-novel approach of basing stories on the author’s own life. Tsuge had finally found a venue giving him the artistic freedom he craved.

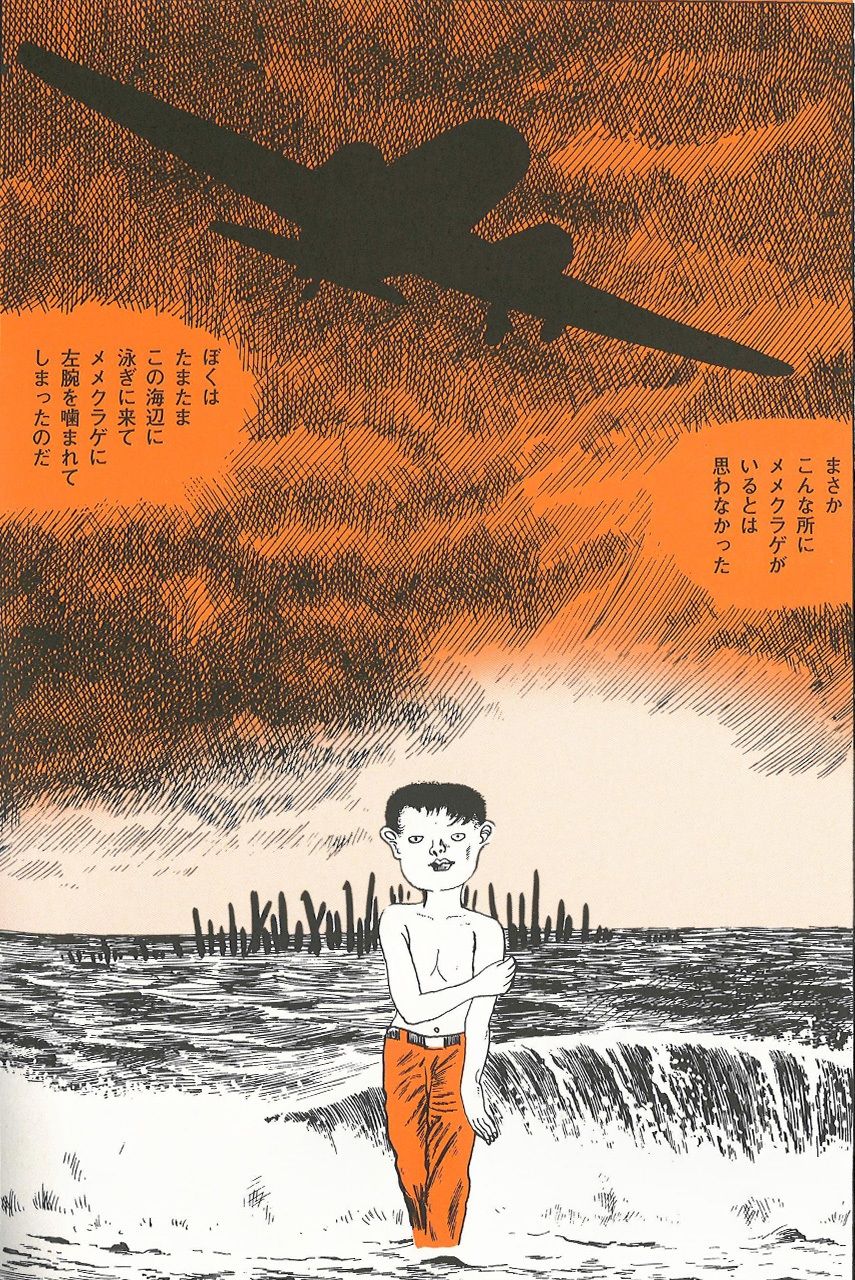

From Red Flowers in the October 1967 issue, Tsuge contributed a number of short works based on his travels, as well as masterpieces like The Mokkiriya Tavern Girl. A special edition of Garo, published in June 1968, was centered on Tsuge’s works, including his Nejishiki, which straightforwardly depicted an irrational dream and won high praise.

Tsuge Yoshiharu’s Nejishiki is one of his most famous works. (© Tsuge Yoshiharu/Seirin Kōgeisha)

After five years, Tsuge’s Master of the Willow Inn was his final contribution to Garo in 1970. He was highly influential on young manga creators, and the underground, surreal style he helped pioneer became known as Garo-kei.

In 2020, Tsuge received an honorary award at the Angouleme International Comics Festival, where he was introduced as “the Jean-Luc Godard of manga.” His works have been published in French and English, and he has enthusiastic fans around the world. Garo was the main venue for his major works.

A Literary Feeling

When Garo was founded, Mizuki Shigeru stood alongside Shirato Sanpei as one of its main stars. His works for the magazine include a remake of an earlier hit for the rental market featuring the yōkai boy Kitarō, and The Man Who Couldn’t Catch a Star, a series based on the life of Kondō Isami, who was a shogunate loyalist at the time of its fall.

Other talented creators with a rental manga background flourished in the pages of Garo. Nagashima Shinji depicted the lonely inner lives of young city-dwellers, while Tatsumi Yoshihiro, who is said to have coined the term gekiga, laid bare the reality of human existence. Takita Yū presented the nostalgic series of short stories Terashima Neighborhood Mystery Tales, and Tsuge Yoshiharu’s brother Tsuge Tadao depicted people left behind by society with an unsentimental edge.

Young winners of the prize for new creators also expressed their ambition in print. Hayashi Seiichi’s Red Colored Elegy was influential on youth culture, and even inspired a hit song of the same name, written and composed by the folk singer Agata Morio.

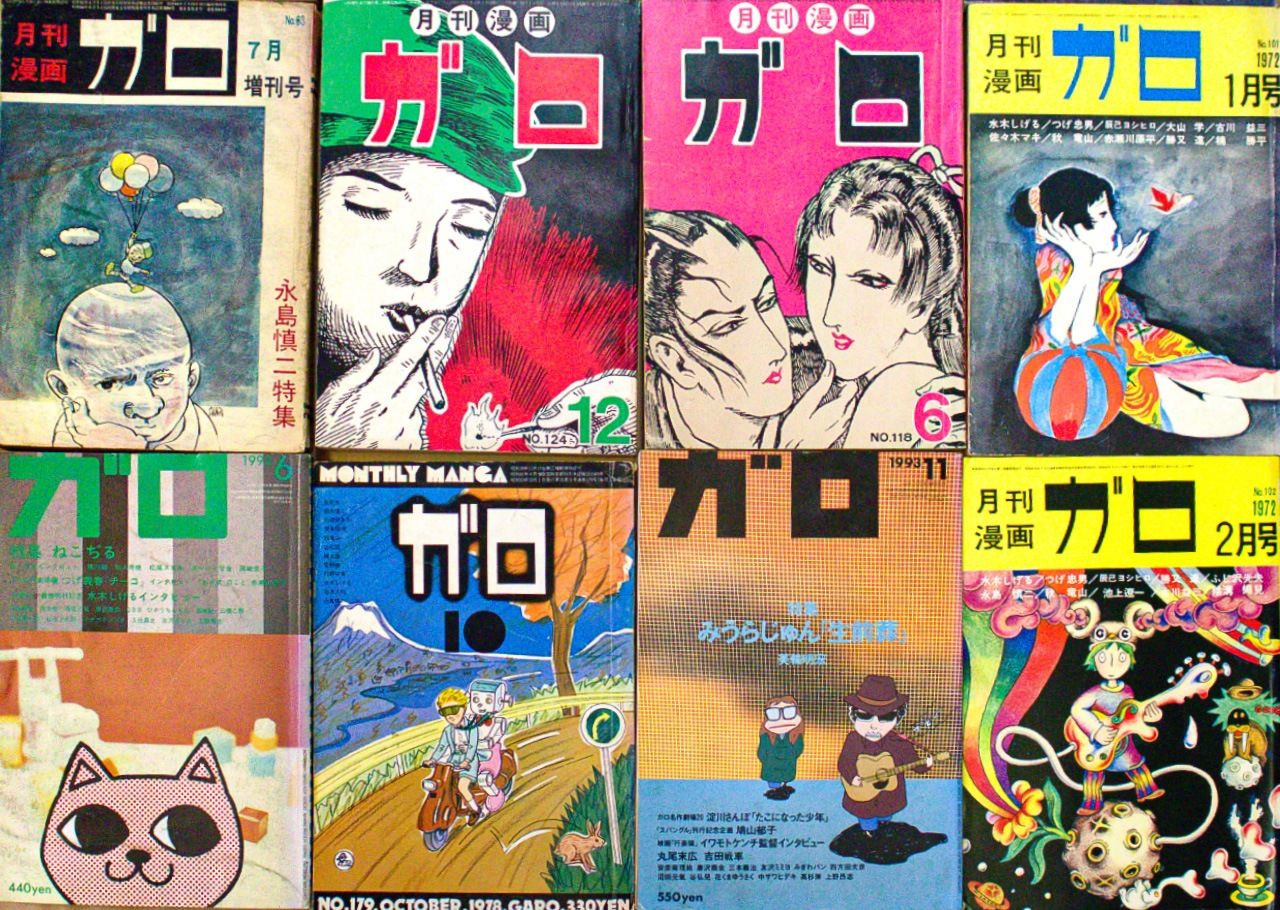

Creators working in many genres appeared in Garo. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

Garo’s achievement into the 1970s was its overturning of truisms like the idea that manga was lowbrow or only for children. The critic Kure Tomofusa saw the magazine as occupying the same space in comics that literary fiction did for the novel.

Tezuka’s Rival Com

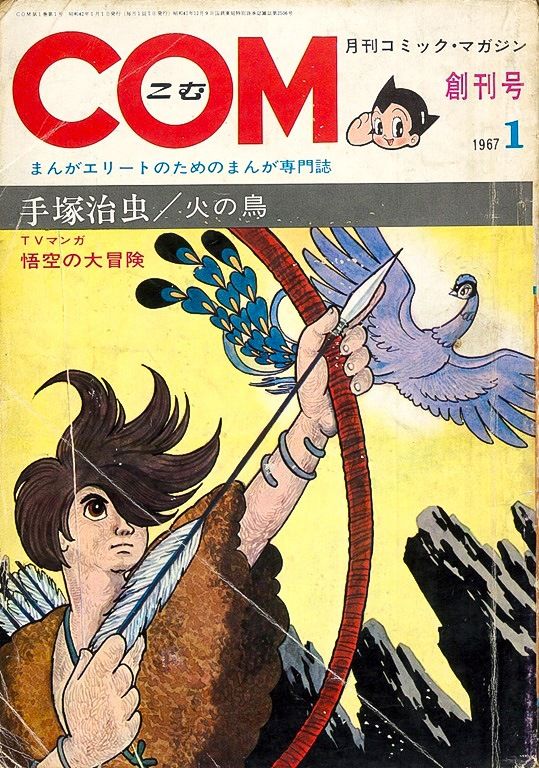

In December 1967, Tezuka Osamu’s company Mushi Pro Shōji launched the magazine Com. This was a platform for Tezuka to publish experimental works like his masterpiece Phoenix, which was seen as a response to The Legend of Kamui. Ishinomori Shōtarō’s Jun and Nagashima Shinji’s Fūten also appeared in Com. The magazine’s focus on discovering new writers, as well as reviews and industry news, showed the influence of Garo.

The first edition of Com. (© Nakano Haruyuki)

New creators who appeared in Com included Takemiya Keiko, who later became well known for her manga aimed at girls like The Poem of Wind and Trees. Manga enthusiasts across Japan got in contact via the magazine and formed networks. This led to the holding of manga fan festivals, and gatherings like Comiket focused on the exchange of dōjinshi or self-published works.

Various editions of Com. (© Nakano Haruyuki)

In February 1968, major publisher Shōgakukan launched a new magazine called Big Comic targeting young men; the first edition included work by Tezuka Osamu, Shirato Sanpei, Ishinomori Shōtarō, Mizuki Shigeru, and Saitō Takao. The chief editor is said to have commented, “We’re aiming to produce Shōgakukan’s version of Garo.” A sequel to the original The Legend of Kamui was published in the magazine from 1988.

Around 1970, there was a wave of new comics from major publishers, and many young mangaka active in this manga boom got their start in either Garo or Com.

Expanded Possibilities

In 1967, the top manga aimed at boys had a circulation of over 1 million. By contrast, at their peak, the circulations of both Garo and Com remained in the tens of thousands. As it struggled to make a profit, Garo became notorious for its meager payments to mangaka. Com ceased publication at the end of 1971. The first part of The Legend of Kamui finished the same year at Garo, but the magazine continued to scrape along through a shakeup in its management, the death of Nagai in January 1996, and other trials, before effectively halting publication in 2002.

Garo played a huge role in the development of manga by placing more weight on what authors wanted to say and have readers experience than on commercial viability. It published distinctively original and novel works that appealed to adult readers with a depth to compete with films and novels, expanding the possibilities of expression for manga.

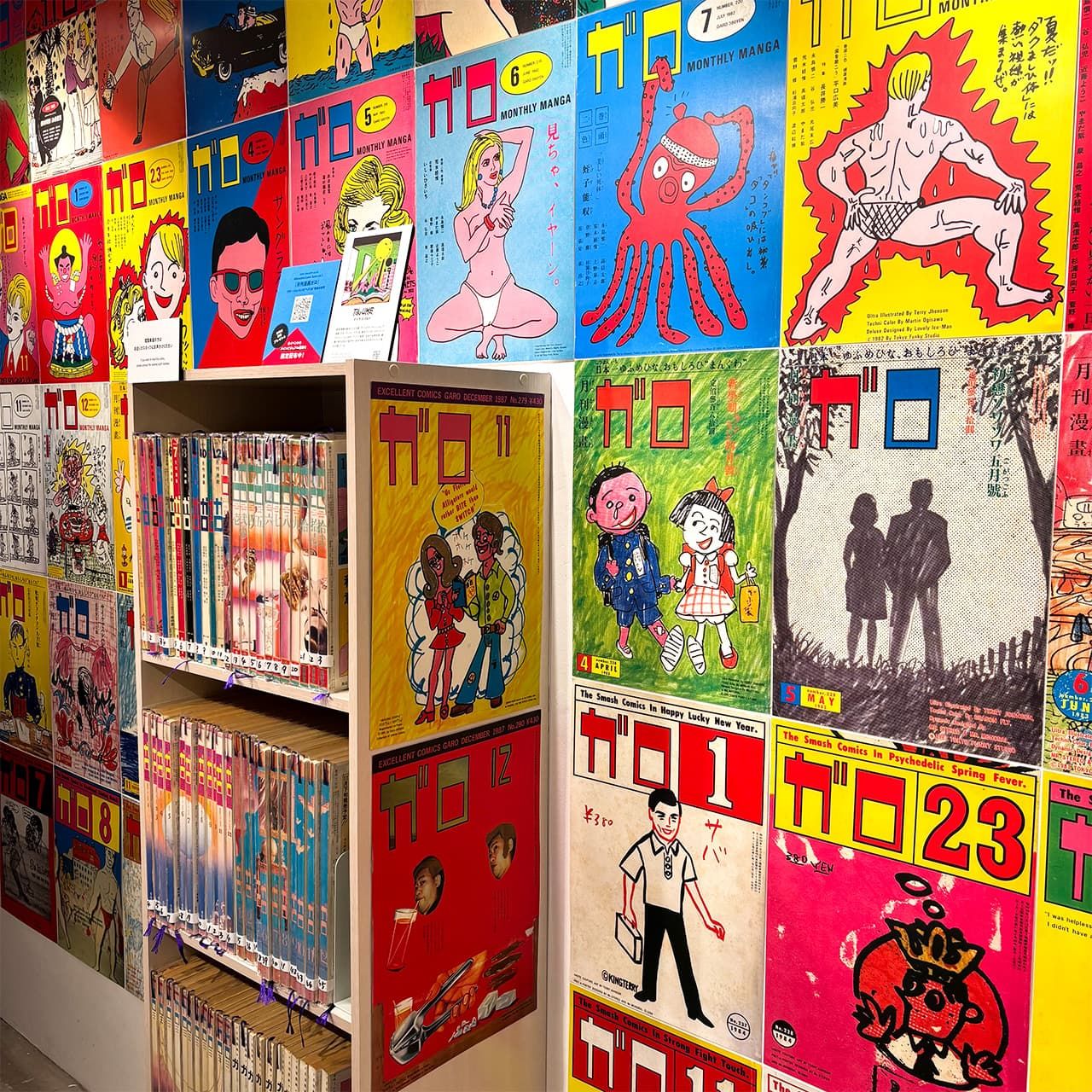

An exhibition of the works of Yumura Teruhiko, who drew covers for Garo in the 1970s and 1980s, and is an exemplar of the hetauma “bad but good” aesthetic. Photograph taken in July 2025 in Tokyo. (© Kenelephant)

Information on Works Mentioned

Note that details of English translations are based on readily available information and may be incomplete.

- Shirato Sanpei’s The Legend of Kamui is translated by Richard and Noriko Rubinger from Kamui den. His Ninja Bugeichō: Kagemaru den (Ninja Bugeichō: The Legend of Kagemaru) is as yet untranslated.

- Works by Tsuge Yoshiharu are translated by Ryan Holmberg in various collections: The Phony Warrior (Uwasa no bushi), The Swamp (Numa), and Chirpy (Chīko) in The Swamp; Red Flowers (Akai hana) in Red Flowers; and Nejishiki, The Mokkiriya Tavern Girl (Mokkiriya no shōjo), and Master of the Willow Inn (Yanagiya shujin) in Nejishiki.

- Hayashi Seiichi’s Red Colored Elegy is translated by Taro Nettleton from Sekishoku erejī.

- Tezuka Osamu’s Phoenix is translated by Dadakai (Jared Cook, Shinji Sakamoto, and Frederik L. Schodt) from Hi no tori.

- Mizuki Shigeru’s The Birth of Kitarō, translated by Zack Davisson from Kitarō no tanjō as the first episode in a collection of the same name, is taken from Garo (the other episodes come from other magazines). Mizuki’s Hoshi o tsukamisokoneru otoko (The Man Who Couldn’t Catch a Star) is as yet untranslated.

- Terashima chō kitan (Terashima Neighborhood Mystery Tales), Jun, Fūten, and Kaze to ki no uta (The Poem of Wind and Trees) are untranslated.

(Originally published in Japanese on September 22, 2025. Banner photo: The pioneering manga magazine Garo. © Matsumoto Sōichi.)

manga art publishing Mizuki Shigeru Tezuka Osamu Manga and Anime in Japan Tsuge Yoshiharu