Shinjuku: Tokyo’s Hub of Diversity and Sexuality

Society Gender and Sex- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Accepting Neighborhood

I was a regular visitor to Shinjuku from 1995 to 2003, when I worked as a hostess in the cross-dressing bars and “new half” pubs on Shinjuku Kuyakusho-Dōri. Before going in to work, I would shop for clothes and shoes at the Subnade underground shopping center near the Shinjuku-Dōri thoroughfare and buy cosmetics at the Isetan department store, where the counter staff would teach me the latest make up techniques. In summer, Isetan and Marui were my go-to spots for extra-tall yukata and bathing suits. Once I even bought an allegedly silver ring from the dodgy-looking and probably illegal stall that would sometimes appear in the square outside the east exit of Shinjuku Station. I often went for Korean barbecue, Taiwanese food, or fare at standard Japanese izakaya with my friends in the area, and met dates at Nakamuraya, the glass-fronted tearooms that overlook Shinjuku-Dōri.

A cross-dresser in Shinjuku’s Kabukichō district in 1997.

I was never refused entry to an establishment for being transgender, and never had any bad experiences. On the contrary, restaurant proprietors were overly nice to me and the men at the stalls selling isobe yaki, mochi wrapped in seaweed, would compliment me on my looks and give me discounts. In Shinjuku, well before the term “LGBT” was invented, people always knew that the world was a diverse place. For business operators in Shinjuku, a diverse clientele was a given.

This acceptance of diversity was not limited to sexual minorities. During the time that I frequented the neighborhood, Iranians, Turks and other Middle Eastern men were a common sight, and I was often the subject of their advances: they told me that I would be considered beautiful in the Middle East. Shinjuku was also home to many Thai women who worked in bars and clubs, some of whom would often take me to an “underground” Thai restaurant in the early morning after we got off work. I was unprepared for the spiciness of authentic Thai cuisine! Kabukichō had also long been home to many Taiwanese, and they were later joined by mainland Chinese (comprising factions from Guangdong, Fujian, Shanghai, and Beijing) who competed with Japanese yakuza for power in a world resembling Hase Seishū’s novel Fuyajō (Sleepless Town). Shinjuku may be described as a generous area that has historically accepted diversity in terms of ethnicity as well.

Before Shinjuku Was Shinjuku

This brings us to the question of how this diverse neighborhood came into existence. The answer is long and complex.

The history of Shinjuku begins in 1698, when part of a residence located on the Kōshū Kaidō, a road running west from the city, belonging to a daimyō named Naitō from what is now Nagano Prefecture was converted into a shukuba: a post station for travelers. The shukuba was located somewhat east of the current center of Shinjuku, toward Yotsuya.

Jump forward to 1885, when Shinjuku Station was established not in Naitō-Shinjuku, but in Tsunohazu-mura, west of the fork in the road that marked the outskirts of the shukuba precinct. There was not a single house in the vicinity, and the rail station was surrounded by fields and zelkova trees. Used mostly by freight trains, the station saw fewer than 50 passengers per day. Compare that with the 3.53 million passengers who now alight or disembark at Shinjuku Station every day, making the station the world’s busiest, and you can see just how extraordinary the growth of the last 133 years has been.

As late as the 1920s, Shinjuku remained the western outpost of what was then Tokyo City: the end of the tramline. But the great Kantō earthquake of 1923 would change everything. While the bustling neighborhoods of Ginza and Asakusa were decimated by the disaster, Shinjuku, on the Yamanote—the elevated “hilly side” of the city—got off relatively unscathed. (To be precise, Shinjuku is located on the edge of what was then called the Musashino area, which outlies Yamanote.) After the earthquake, many Tokyoites moved from hard-hit areas into Musashino and Tama, causing western Tokyo to prosper. With Shinjuku Station now serving as the rail terminal for Tokyo’s western suburbs, Shinjuku would at last have its heyday as an entertainment center for West Tokyo. Shinjuku saw its prewar peak in the 1930s as a modern urban center replete with department stores, cinemas, theaters, dance halls, and cafes that catered to the demands and tastes of a burgeoning urban middle class composed mostly of professional workers.

The Black Market Years

Shinjuku’s glory days would not last forever. Most of the neighborhood was literally reduced to ashes on May 25, 1945, by the US Army’s Yamanote air raid. But in August that year, immediately after the end of World War II, black markets began to pop up amid the destruction. There were the Ozu-gumi and Nohara-gumi stalls outside Shinjuku Station’s east exit, the Wada-gumi shops between the east and south exits, and the Yasuda-gumi location outside the west exit. Of all the markets, the Wada-gumi was the biggest.

And that ends my somewhat long-winded account of the history of Shinjuku. I do believe that these vast black markets were at the root of Shinjuku’s diversity.

Shinjuku’s markets really were “black,” in that all transactions there were illegal. However, they sold a variety of goods that were unavailable in the controlled, heavily rationed economy of the day. Food, liquor, clothing: everything was for sale, and people swarmed to the markets to buy it. Sex was also for sale. Many of the south exit’s numerous streetwalkers took clients in makeshift brothels situated in black markets. Some of these were in fact male prostitutes dressed as women.

In 1949, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers ordered the removal of the stalls. The black markets around Shinjuku station were dismantled, and their proprietors dispersed throughout the Shinjuku area, with most heading to the Golden-gai or Hanazono-gai, which is currently a cluster of bars and restaurants behind Hanazono Shrine. For a period of eight years after the 1950 relocation, the Golden-gai was a blue zone (a red-light district that was not officially sanctioned and was therefore frequently raided by police), and sold both liquor and sex. Back then, the Golden-gai rivalled red-zoned Shinjuku 2-chōme (where prostitution was tacitly allowed, meaning no police raids), itself the busiest red-light district since the prewar era.

Naka-Dōri in Shinjuku 2-chōme during the red-zone years (1958).

The Great Switch

The Anti-Prostitution Act of 1957 put an end to the sex trade and caused the blue zone to go into decline. This cleared the way for the arrival of cross-dressing male prostitutes who had saved money from turning tricks near Shinjuku Station’s west exit and the Tachikawa military base. These “girls” bought the rights to businesses on the cheap and started up small bars, a few of which were still operating in the Golden-gai when I frequented it in the 1990s. It was against this backdrop that Kamo Kozue, a Yomiuri Shimbun employee and senior member of Fuki, a secret society for cross-dressers, established a cross-dressing bar of the same name in the Hanazono Gobangai. Later renamed Kozue, this bar would go on to be a touchstone for the cross-dressing culture to follow.

Members of the secret cross-dressing club Fuki posing for a photo in front of the refurbished Shinjuku Station building in June 1964.

My former employer—the bar June, located in the Hanazono Gobangai—opened after Kozue closed, and was the heart of the cross-dressing community in the 1980s and 1990s. The bar that June replaced had been run by a beautiful cross-dressing male prostitute, since deceased, whose photo was always on display next to the bottles of liquor.

The role as provider of liquor and sex that had been performed by the blue-zoned area behind Hanazono Shrine was subsequently transferred to Kabukichō 1-chōme, on the West side of Kuyakusho-Dōri (behind the city office).

The Chidori-gai, situated to the south of the intersection of Shinjuku-Dōri and Gyoen-Ōdōri (the road that separates 2-chōme from 3-chōme), was full of small bars that had their origins in the black markets. As early as the 1950s the Chidori-gai had a reputation for having lots of gay bars, but the extension of Gyoen-Ōdōri in 1968 forced those bars to close. From 1969 through 1972, there was a surge in gay bar openings on the other side of Shinjuku-Dōri, in the formerly red-zoned Shinjuku 2-chōme. As I recently discovered through my research, Shinjuku’s gay area has its roots in the Chidori-gai, but it was the closure of the Chidori-gai that caused the 2-chōme gay area to come into existence.

Finally, I had solved the mystery of the neighborhood-wide switch in in sexual orientation—highly unusual even by international standards, with a place that had for many years been where men went to meet women transformed almost overnight into a gay “Mecca.” Thus, one may see how the sexual diversity of Shinjuku—including its segmentation into straight Kabukichō, Hanazono-gai (the birthplace of the cross-dressing community), and gay (and subsequently lesbian) 2-chōme—was rooted in the postwar black markets, nurtured by the bars that those black markets spawned, and forced to reorganize by the passage of the Anti-Prostitution Act.

Tips for a Night Out

Let me close with a few tips for a night out in diverse 2-chōme.

Naka-Dōri in the gay area 2-chōme as it is today.

While the area around Shinjuku’s Naka-Dōri is home to over 200 gay bars and around 20 lesbian clubs, many of these are run by traditionally minded proprietors and only allow gay men or only lesbians into the premises. Recently, however, the area is seeing more bars that welcome anyone as long as they’re LGBT-friendly, such as gay book café Okamaruto and lesbian foot spa café Don’yoku. I believe we are going to see more such “open” spaces in the future.

While the prevalence in the 2000s of the term “gender identity disorder” and the resultant medicalization of transgender people caused a reduction in the number of cross-dressing bars, in Kabukichō and Hanazono Sanbangai, where it all began, Jan June (a descendent store to the original June) remains in business, keeping the tradition alive. Open to both men and women, bars like this are an inexpensive option for a casual drink.

For those who want to drink in style, I recommend “new half” club Memory on Kuyakusho-Dōri in Kabukichō 2-chōme, whose proprietor is just as pretty now as she was 20 years ago. And if you want to see a “new half” show, I recommend Black Swan Lake in Kabukichō, which has been in business for 40 years and is even included on the Hato Bus night sightseeing route.

In Shinjuku, you never know whether the tall woman you just walked past is in fact transgender. That’s what makes it such fun! I urge you to visit Shinjuku if you get the chance.

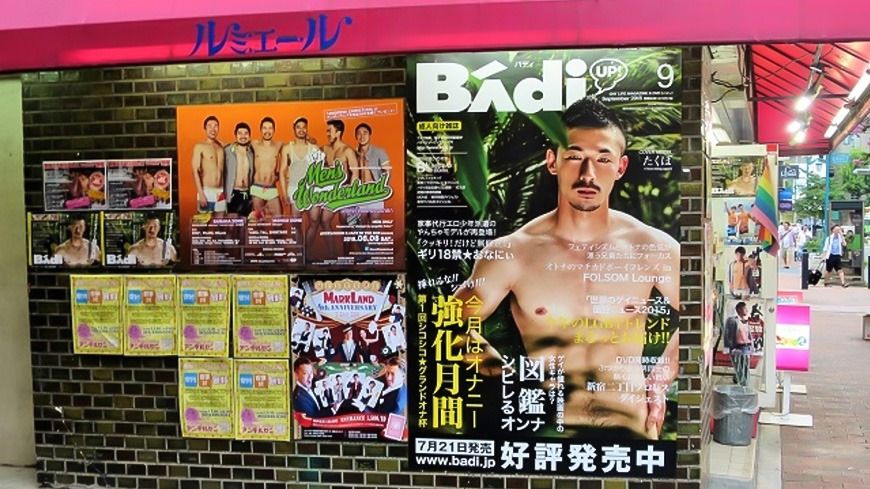

(Originally published in Japanese on February 5, 2019. Editing by Power News. Photographs supplied by Mitsuhashi Junko. Banner photo: Lumiere, an adult gay boutique in Shinjuku 2-chōme.)