Japanese Literature in the Twentieth Century: A Shōwa Retrospective

Historical Fiction and Social Issues: Japanese Books from 1965 to 1974

Books Culture Society Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The fourth part of a series on Japanese literature in the Shōwa era (1926–89) introduces books written from 1965 to 1974 (Shōwa 40–49). While Japan’s economic miracle continued, there were also serious social issues, and the country’s writers tackled diverse themes.

Silence by Endō Shūsaku

Endō Shūsaku (1923–96) was baptized as a Catholic at the age of 12, under the influence of his mother. From the time he was studying literature at Keiō University, he published numerous works with Christian themes. These include Silence, written as he suffered from tuberculosis, and was often close to death. He thought that he would be content to pass on, if he could only complete this work.

The novel is set shortly after the suppression of the Shimabara Rebellion (1637–38), which was led by Christians. A young Portuguese priest called Rodrigo secretly enters Japan, having heard about the apostasy of his mentor, who was conducting missionary work in the country. He establishes contact with the hidden Christians, and writes about the reason he thinks the faith has rooted itself among these poor farmers (translation by William Johnston).

I tell you the truth—for a long, long time these farmers have worked like horses and cattle; and like horses and cattle they have died. The reason our religion has penetrated this territory like water flowing into dry earth is that it has given to this group of people a human warmth they never previously knew.

Even when they are cruelly tortured, they refuse to tread on a Christian image known as a fumie in a symbolic renunciation of their beliefs. Rodrigo wrestles with the question of why God has remained silent in response to such martyrdom.

Betrayed by Kichijirō, one of his Christian followers, Rodrigo is captured by the authorities and pressed to abandon his faith. Each time, he refuses, one of the Christians is executed. Kichijirō, who ultimately trampled the fumie to save his own life, had asked the priest, “Why has Deus Sama imposed this suffering upon us?” and “Father . . . what evil have we done?”

Rodrigo’s thoughts are in turmoil.

“Already twenty years have passed since the persecution broke out; the black soil of Japan has been filled with the lament of so many Christians; the red blood of priests has flowed profusely; the walls of churches have fallen down; and in the face of this terrible and merciless sacrifice offered up to Him, God has remained silent.”

Throughout his life, Endō grappled with the question of what Christianity means for Japanese people. His answer can be found in the path Rodrigo chooses amid his despair.

- Chinmoku is translated as Silence by William Johnston.

Zero Fighter by Yoshimura Akira

In the afterword to Zero Fighter, Yoshimura Akira (1927–2006) notes, “I was inspired to write by my conviction that writing the history of the Zero fighter, from its creation to its final days, would show the nature of the war that Japan fought.”

The book opens in the evening of March 23, 1939, as two heavily loaded oxcarts, carefully covered over with sheets, make their quiet departure from the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries aircraft factory in Nagoya. The men holding the oxen’s reins carry lanterns as they go.

The carts are carrying a completed prototype Zero fighter, separated into fuselage and wings, to an airfield in Kagamihara, Gifu, 48 kilometers away. It is a 24-hour journey, but due to the narrow, unpaved roads, this is the only way to transport the machine without damaging it.

While Japan could produce the high-tech Zero fighter, at the time the best fighter plane in the world, its poverty meant that it did not have the capacity to upgrade its roads, and was forced to rely on this basic form of transportation. In this scene, Yoshimura saw the essence of the tragedy of Japan’s reckless charge into war.

In putting together his substantial story based on the facts, Yoshimura interviewed key figures like the Zero designer Horikoshi Jirō. The fighter went into operation in 1940, and showed initial success in the Sino-Japanese War. Toward the end of World War II, however, mass-produced US airplanes were able to surround the Zeros and shoot them down, exploiting weaknesses like inadequate armor plating.

In January 1945, a major B29 bombing raid killed young male and female student workers at the Nagoya aircraft plant. Yoshimura shows the true nature of war by including the suffering of ordinary people who worked to produce the fighters. The author himself was born and raised in a working-class shitamachi part of Tokyo, and worked in a munitions factory as a student.

Yoshimura’s typical approach, based on careful research and extensive use of source materials, is called “documentary literature” (kiroku bungaku). While this emphasizes an objective standpoint, he constructs rich narratives through his insight into human nature and literary expression. Yoshimura takes on a wide range of genres, and other fine works include Kuma arashi (The Bear Storm), about a 1915 brown bear attack in Hokkaidō, and Sakuradamon gai no hen (Sakurada Gate Incident), depicting the turmoil in the last days of the shogunate and the assassination of Ii Naosuke. (Neither has yet been translated into English.)

- Reishiki sentōki is translated as Zero Fighter by Retsu Kaiho and Michael Gregson.

Clouds Above the Hill by Shiba Ryōtarō

Before getting his start as a novelist, Shiba Ryōtarō (1923–96) studied at the Osaka University of Foreign Studies and was a journalist for the Sankei Shimbun. In 1960, he won the Naoki Prize for Fukurō no shiro (Owls’ Castle), earning further popularity from works like Ryōma! The Life of Sakamoto Ryōma: Japanese Swordsman and Visionary (1963), about the legendary historical figure, and Moeyo ken (Burn, O Sword) (1964), which told the story of shogunate loyalist Shinsengumi vice-commander Hijikata Toshizō. It was Clouds Above the Hill, however, that elevated him into a national author.

“A small island nation was about to enter a period of great cultural change.” The novel’s opening sentence looks ahead to the fresh vitality of the Meiji era (1868–1912).

The story begins in Matsuyama in what is now Ehime Prefecture, Shikoku. Its three main characters are Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902), who revolutionized the traditional poetic forms of haiku and tanka with a fresh focus on realism; his schoolmate Akiyama Saneyuki (1868–1918); and Akiyama’s older brother Yoshifuru (1859–1930). Based on historical events, the narrative follows this trio from their youth until the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05.

Saneyuki joins the navy, where he serves as an officer under Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, contributing to the spectacular destruction of Russia’s Baltic Fleet at the Battle of Tsushima. In the army, Yoshifuru commands the cavalry, which defeated Russia’s formidable Cossacks with machine guns. This is the climax of the story.

Shiba writes of the Meiji era as follows.

The Meiji Restoration [in 1868] saw the end of the arrogant sonnō jōi [revere the emperor and expel foreigners] attitude of the last years of the shogunate. It was also the start of the period of opening up the country to the West, in which there was a realistic attitude that was sometimes almost obsequious. The Japanese of the late nineteenth century were more pragmatic than at any other period in history.

Concerning the Russo-Japanese War, he notes: “It would be a difficult war to win, and indeed, the military itself had tipped its hand, honestly revealing its weakness and its willingness to deploy diplomacy to bring the conflict to a halt if necessary.”

This presents a striking contrast with Japan’s military in the Shōwa years, which he describes as “shrouding itself in secrecy, so that both it—and the state as a whole—became mystical, false images.” Shiba concludes that the delusion of being a great power after the Russo-Japanese War detached Japan’s leaders’ thinking from reality, laying the path to the devastation of World War II.

Incidentally, a survey at the Shiba Ryōtarō Memorial Museum found that the author’s favorite work among readers was Clouds Above the Hill, followed by Ryōma! and Burn, O Sword.

- Saka no ue no kumo is translated as Clouds Above the Hill by Juliet Winters Carpenter, Paul McCarthy, and Andrew Cobbing.

- Ryōma ga yuku is translated as Ryōma! The Life of Sakamoto Ryōma: Japanese Swordsman and Visionary by Juliet Winters Carpenter, Paul McCarthy, and Margaret Mitsutani.

The Twilight Years by Ariyoshi Sawako

After graduating from Tokyo Women’s Christian University, Ariyoshi Sawako (1931–84) made her debut in 1959 with The River Ki based on her own family’s history in Wakayama Prefecture. Her bestselling works cover a broad range, from classical performing arts to social issues. Although she died at just 53, she was one of the leading female writers of her time.

In The Twilight Years, Akiko struggles alone to look after her father-in-law Shigezō, who is in his eighties and suffering from dementia. Her husband Nobutoshi works at an elite trading house and is in the prime of his career; he leaves all caring duties to her, paying no attention. Meanwhile, their only child Satoshi is busy studying for university entrance exams.

The family lives in a house built by Nobutoshi in Suginami, Tokyo, which had an extension in the garden where his retired parents could live. But after his mother died, his father rapidly developed dementia. Shigezō could no longer recognize Nobutoshi, and he would forget he had eaten, complain of hunger, and gobble up all the prepared dishes in the kitchen. Later, he began to leave the house and go wandering off.

Akiko has a job in a law office, but she is forced to take leave. Remembering Shigezō’s unpleasant comments about “working women,” she nonetheless devotes herself to his care. However, she finds it impossible to look after him in his severe state, and when she asks for help at a welfare office, they cannot find a care facility for him. Akiko laments how Japan is lagging behind in care for the elderly, with no measures for tackling issues relating to the aging population.

Even so, this 1972 novel provides a bright depiction of Japan in its high-growth era. There is humor in Shigezō’s activities, while Akiko tries to look after him after at home, gradually winning the cooperation of the rest of the family. Evocative phrases recall the period through its leisure boom, electric rice cookers, two-day weekends, driving enthusiasts, and pants fashions, as well as its rising prices and photochemical smog.

The book became a hit, raising awareness about the problem of dementia. Ariyoshi writes that the life expectancy of the time in Japan was 74 for women and 69 for men. By 2024, these figures had risen to 87 for women and 81 for women. Japanese lives have become longer, and the issues of dementia and caring that Ariyoshi warned about have become more serious, leading to further tragedies.

- Kōkotsu no hito is translated as The Twilight Years by Mildred Tahara.

- Kinokawa is translated as The River Ki by Mildred Tahara.

The Grand Family by Yamasaki Toyoko

The novel Karei naru ichizoku (The Grand Family) paints a vivid picture of the ambitions and desires of entrepreneurs in Japan’s high-growth era. The finance and steel industries at the heart of the story were symbolic of the prosperity of this time. (As yet, the novel has not been translated into English).

Yamasaki Toyoko (1924–2013) was born in the merchant town of Senba, Osaka. After graduating from Kyoto Women’s University in 1944, she joined the Osaka bureau of the Mainichi Shimbun. There she worked under future author Inoue Yasushi, who encouraged her to start writing, and at first, she took merchant families as her subject. However, after the bestselling success of her 1965 novel Shiroi kyotō (The White Tower), which was set in a university hospital and probed deeply into medical taboos, she focused on social issues.

The Grand Family centers on Manpyō Daisuke, who heads a bank and one of the leading zaibatsu in the Kansai region. Hearing of planned government mergers of financial institutions, Manpyō schemes to come out on top. However, his son Teppei, who is executive director of a steel company subsidiary in Manpyō’s business empire and a man of firm principles, constantly clashes with him, leading to catastrophe. According to Yamasaki, the book is about three types of evil: “ politics, corporate skullduggery, and bureaucratic misdoings.”

Meticulous research underpins her writings. In The Grand Family, she received cooperation from Tajitsu Wataru, the head of Mitsubishi Bank, who gave a detailed account of the failed talks about a merger with Dai-Ichi Bank, which would have shaken up Japan’s banking industry. In a pacifist Japan, she said that corporate battles gave the clearest pictures of people, revealing their cravings and ugliness or wisdom and pure hearts.

Almost all of Yamasaki’s works have been adapted and The Grand Family is no exception, with film and television versions. She took profound themes and presented them on an epic scale, and no other writer has since emerged with such a grand vision.

Selected Japanese Literature (1965–74)

- Shiroi kyotō (The White Tower) by Yamasaki Toyoko (no English translation) (1965)

- Freezing Point by Miura Ayako, translated by Hiromu Shimizu and John Terry from Hyōten (1965)

- The Doctor’s Wife by Ariyoshi Sawako, translated by Wakako Hironaka and Ann Siller Kostant from Hanaoka Seishū no tsuma (1966)

- Silence by Endō Shūsaku, translated by William Johnston from Chinmoku (1966)

- The Silent Cry by Ōe Kenzaburō, translated by John Bester from Man’en gannen no futtobōru (1967)

- Zero Fighter by Yoshimura Akira, translated by Retsu Kaiho and Michael Gregson from Reishiki sentōki (1968)

- Clouds Above the Hill by Shiba Ryōtarō, translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter, Paul McCarthy, and Andrew Cobbing from Saka no ue no kumo

- The Japanese and the Jews by Isaiah Ben-Dasan (Yamamoto Shichei), translated by Richard L. Gage from Nihonjin to Yudayajin (1970)

- The Twilight Years by Ariyoshi Sawako, translated by Mildred Tahara from Kōkotsu no hito(1972)

- Karei naru ichizoku (The Grand Family) by Yamasaki Toyoko (no English translation) (1973)

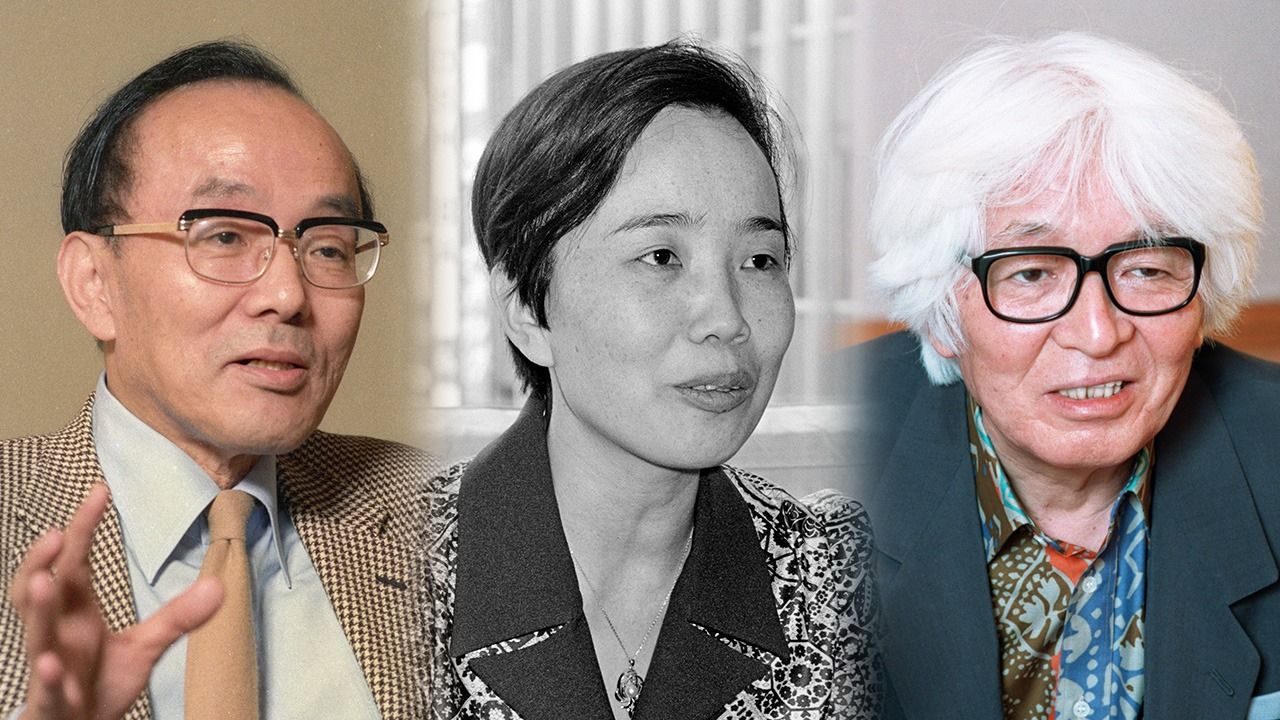

(Originally published in Japanese on October 16, 2025. Banner photo: From left: Endō Shūsaku [© Kyōdō], Ariyoshi Sawako [© Jiji], Shiba Ryōtarō [© Jiji].)