Crossing Borders Without Translation: US Writer Gregory Khezrnejat Wins Award for Japanese Novella

People Culture Society Language- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Yearning for Kyoto

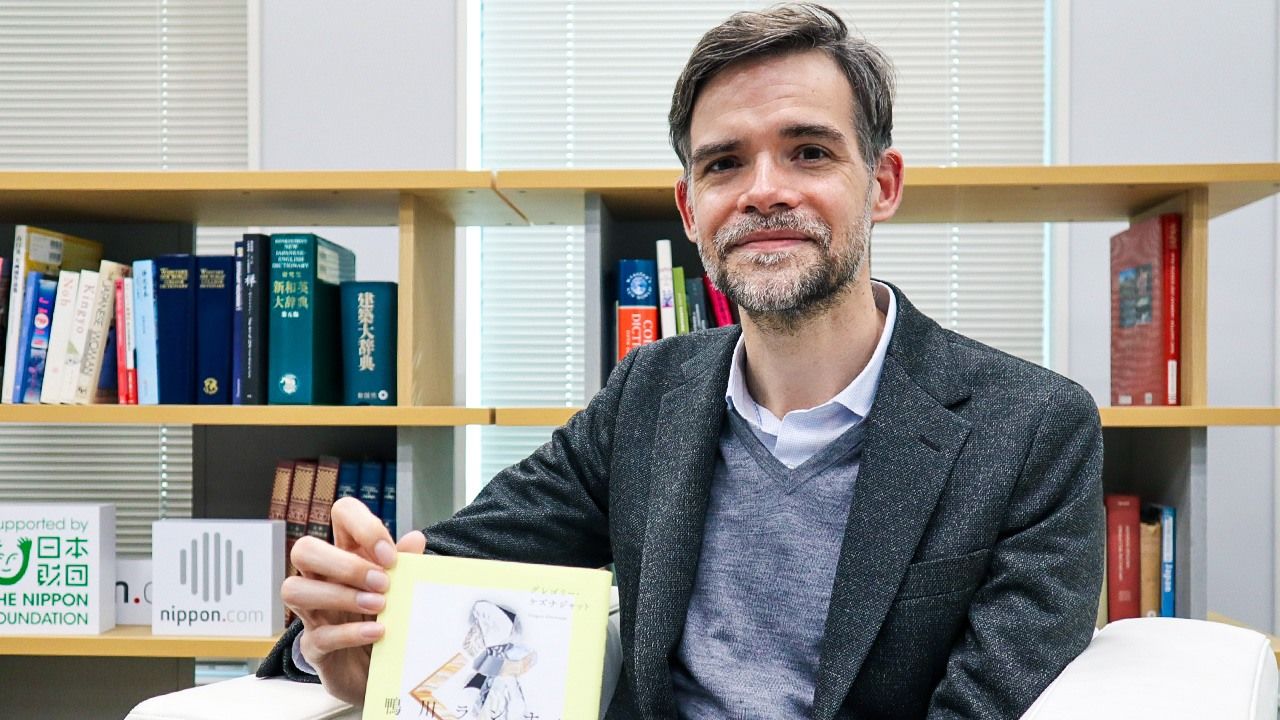

The Kyoto Literature Award was launched in 2019 with a general category and one for writers whose first language is not Japanese. In the spring of 2021, US writer Gregory Khezrnejat’s entry Kamogawa rannā (Kamogawa Runner) was selected as the overall winner of the prize in both categories.

Told in the second person throughout, Khezrnejat’s novella centers on a young American who studies Japanese in high school and college. Yearning to return to Kyoto, where he spent two weeks at the age of 16, he applies to the JET Program, and is assigned to work as an assistant language teacher at a junior high school in a town neighboring the former capital. He moves on to work at an English conversation school, and then encounters the literature of Tanizaki Jun’ichirō. The streets of Kyoto and the Kamogawa riverside form a backdrop to the main narrative.

Although fiction, there are many similarities with Khezrnejat’s own life. As a foreign take on Kyoto, the novel also brings to mind the 1997 book Ichigensan (trans. by Takuma Sminkey as Ichigensan: The Newcomer) by the Swiss-born writer David Zoppetti, which was nominated for the Akutagawa Prize. With Tanizaki’s Shunkinshō (trans. by Howard Hibbett as A Portrait of Shunkin) as a motif, this book depicts the narrator’s alienation in the city, his falling in love with a blind woman, and their separation.

Meanwhile, alongside the everyday life of a foreign resident in Kyoto, Kamogawa Runner explores topics like language, translation, and communication. In the opening of the story, the 16-year-old protagonist visits a temple, where he hears the word omamori explained as meaning “amulet” and agonizes over whether something is lost through translation—one of the big questions the work addresses.

Challenged and Fascinated

Khezrnejat was born in Greenville, South Carolina, in the United States. His father was born in Iran and speaks both English and Persian.

“As a child, I thought it was amazing that my dad could switch between two different languages. It was like having two different selves. When letters arrived from his family in Iran, Dad would read them, and say what they were about in English. ‘That writing that doesn’t even look like letters to me actually means something!’ It was so ordinary, but to me it was impressive.”

He encountered Japanese as a high school student. At the time, Greenville was enthusiastic about drawing Japanese companies to the city, and there were Japanese classes at Khezrnejat’s high school. As with Persian, he was challenged and fascinated by the use of a completely different script from English.

While majoring in computer science and English literature at college, he continued his studies of Japanese, and came to Japan in 2007 as an assistant language teacher. He did not return home after his contract finished, instead choosing to become a graduate student at Kyoto’s Dōshisha University.

“Partly I just wanted to stay in Kyoto, but I also wanted to be on the inside, researching in Japanese, rather than looking at Japanese literature from the outside as a graduate student in the United States.”

Khezrnejat now lives in Tokyo, but travels to Kyoto every few months or so. “It isn’t my hometown, but I lived there for ten years, so every time I hear people speaking in Kansai-ben, I feel, ‘Ah, I’m home.’”

You, the Narrator

It took some trial and error to choose a narrative point of view for Kamogawa Runner.

“Each perspective has its merits, but with the first person, there might be some sense that the nonnative narrator is making an emotional plea to the likely native reader. With the third person, the narrator would be lining up alongside the reader in observing the protagonist. This was one reason why I decided to use the second person. I felt it offered the mechanics for suitably blurring the boundaries between reader and narrator. It also allowed me to create some distance from the protagonist, whose experiences overlap with my own.”

At the end of October, the story was published in a volume together with the story Igen (Tongues).

Mike, the main character of Tongues, goes to stay at the home of his girlfriend Yuriko after the conversation school where he works folds. While he is struggling with his work as a freelance technical translator, a friend introduces him to the opportunity to act as a “priest” at wedding ceremonies. Whatever he does in his daily life, he is always viewed as an English speaker. Even during sex, his girlfriend insists on using English, while in the priest job, he is asked not to make his Japanese too fluent.

“Because I wrote Tongues in the first person, I wanted to run with this, emphasizing Mike’s perspective. I tried to include some humor and create something a bit more acerbic. Many English speakers live for a long time in Japan without being able to speak Japanese. Even when they try to perform everyday tasks in Japanese, there’s a powerful, but unspoken, pressure for them to speak their native language, and—like it or not—they’re put in the category of “English-speaking foreigners.” This situation has its comical side, but can also be quite sad, and I wanted to explore it through fiction.”

A Self for Each Language

When Khezrnejat first began learning Japanese, the different words for the first person were a mystery to him. “In English there’s only ‘I,’ so I couldn’t see the difference between boku and watashi. Then when I came to Japan, all the male students around me used ore. I was never sure about when to use each one.”

He also feels a difference between “I” and boku—which, incidentally, is the form of the first person used by Mike in Tongues.

“I feel I have a different identity depending on whether I’m using Japanese or English. Sometimes it’s confusing if I start a conversation in Japanese, and the response comes, ‘Oh, you can speak in English.’ While the other person is presumably trying to meet my needs, it also feels a bit like I’m being chased out of Japanese. It’s not that I’m thinking in English and then translating into Japanese; I’m speaking Japanese from the perspective of another self immersed in the language. It’s easy to think that we express our ‘true self’ in our first language, but I think we develop a new self for each language.”

After winning the Kyoto Literature Award, Khezrnejat was interviewed by his US university, but found it quite challenging. “It was unexpectedly difficult to say what I wanted to say. As my first language, it should be easier to speak in English. But as my literary research and creative work had all been in Japanese, this was the language that came naturally when discussing these topics. I felt in this case that I was actually translating into English, because I wanted to speak Japanese.”

Why Japanese?

US writer Levy Hideo won the Noma Literary New Face Prize in 1992 for his debut work Seijōki no kikoenai heya (trans. by Christopher D. Scott as A Room Where the Star-Spangled Banner Cannot Be Heard: A Novel in Three Parts). In the afterword, he notes that he is often asked why he writes in Japanese. The same must also be true for Taiwanese author Li Kotomi, who won the Akutagawa Prize this year.

“The brilliance of Levy’s works is closely linked to them being written in Japanese. He himself has said that he wanted to speak to the readers of Japan readers directly, rather than in translation,” Khezrnejat notes. “For example, the English version of A Room Where the Star-Spangled Banner Cannot Be Heard might be seen just as the kind of ‘good read’ where a young person discovers himself through spending time in another country and feeling the differences with where he’s from. Translation changes not only the content but also the context of the reader and the act of reading. As someone who read the book in Japanese, I feel like something crucial in the original is lost. I’m not talking about whether it’s good or bad, but it becomes a different work.”

He goes on: “My parents asked why I had to write in Japanese, which they don’t understand. In that sense, it would be nice to have an English translation, but to be honest, if someone offered to do it, I think I’d hesitate. It’s a thorny question.”

For a work written in Japanese, if it is not translated, it cannot become “world literature.”

“I’m not thinking that I want people around the world to read it. Forming the sentences and writing fiction in Japanese is enjoyable in itself. Still, while this wasn’t at the top of my mind, there might have been some resistance to the idea of the supremacy of ‘global English,’” Khezrnejat says. “It’s good that literature crosses borders, but this doesn’t have to come through translation. I think it’s very worthwhile that there are authors writing in Japanese as their second language, and that native speakers like Tawada Yōko are writing in other languages.”

Projection and Translation

Khezrnejat says that Japanese literature as seen in the English-speaking world is always a projection of a desired image of Japan.

“After World War II, there was a wish for a gentle, feminine, traditional Japan, as a good ally—based on an image of Japonism—and the first English translations met these expectations. Japanese works in English today better reflect the true diversity of the literature, but perhaps still reflect changes in the contemporary English-speaking readership.”

Khezrnejat has conducted research into the works and English translations of Tanizaki, but in the future he wants to concentrate on creative activities. He is currently writing two new stories, one of which is set in the American South, inspired by another nonnative writer in Japanese.

“When I read Shiroi kami [White Paper] by Shirin Nezammafi [an Iranian writer twice nominated for the Akutagawa Prize], I was full of admiration for her setting it in Iran rather than Japan. However, during the selection process, it was questioned why such a story needed to be written in Japanese. Perhaps it didn’t meet readers’ expectations. I feel like there’s a desire for cross-border writing in Japanese to produce stories about the experiences of foreigners in Japan. My debut was this kind of book, so I certainly think there’s a place for them. But cross-border literature should have more freedom.”

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Gregory Khezrnejat at the Nippon.com office in Tokyo. All photos © Nippon.com.)