“Oni” and Outsiders in Japanese Cultural History

Society Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The common image of the oni in Japan today is of fierce red or blue creatures with two horns and bulging eyes, wielding metal clubs, as seen, for example, in illustrations to the classic fairy tale Momotarō. The word is sometimes translated into English as “demon” or “ogre.”

Over the centuries, however, the Japanese term’s meaning has shifted. While many researchers in Japan have studied ancient and medieval materials to write about the oni from the viewpoint of literature or folklore studies, scholar Koyama Satoko is the first to trace the image of the oni and its social background from a historical perspective.

“Oni have influenced Japanese hearts and minds from ancient times until today,” says Koyama. “How have people come to grips with these beings and passed on their thoughts about them? Tracing the oni lineage means peering into the psyche of the Japanese people.”

Appearances in Official Histories

From more than 2,000 years ago, it was believed in China that after death people become gui (written with the character 鬼, later used for oni in Japanese), or spirits, and live in the underworld. Gui were talked about as part of the world of folk religions, Confucianism, and Daoism, and also took influence from Buddhism, after it spread to China. The boundary between gui and shen (神, deities) was hazy; some gui might become the object of worship, while others might be brought under control through magic. Gui were also thought to spread disease.

The concept spread to Japan no later than the seventh century, transforming to become more easily accepted.

“From the start oni in Japan had a multifaceted image. In the Heian period [794–1185], mononoke [the spirits of unknown people] were sometimes called oni, but the Chinese idea of using the word for all the spirits of the dead was only partially adopted. In China, gui could be good or evil, but the word oni came to be used only for evil beings in Japan. There was also a strong influence from esoteric Buddhism, which had incorporated the concept of godlike oni.”

Ancient national histories, compiled under imperial orders, include descriptions of oni activities. Nihon shoki, completed in 720, reports how in 544 people called the Mishihase from the northern part of Japan (some scholars suggest they were Ainu or Tungusic) came ashore on the island of Sado. The islanders feared to approach, in the belief that they were oni, and as they hesitated, some of them were abducted.

In Shoku nihongi (797), there is a description of a rumored jujutsushi or sorcerer on Mount Yamato Katsuragi in 699, who could control a godlike oni and make it draw water and gather firewood; if it did not obey, he would prevent it from moving through a binding spell. The later Nihon sandai jitsuroku (901) records a story of how in 887 a woman was eaten by an oni at night in Heiankyō (now Kyoto), also noting that there were stories of 36 other such incidents in the same month.

In the Heian period, there was a belief based on the traditional esoteric cosmology of onmyōdō that on particular nights, there was a danger of being attacked by parades of oni. Many aristocrats were wary about venturing outside on these occasions. The twelfth-century Buddhist cultural history Fusō ryakuki reports that an oni footprint was discovered in the imperial court in 929. It was described as a large footprint with two or three hooves; at the time oni were believed to have two or three toes on each foot.

“As the Nihon shoki account shows, it’s important to note that oni were perceived as landing from elsewhere,” Koyama says. “And even if they were only rumors, stories of oni appearances were reported to the court, and considered sufficiently terrible that they needed to be recorded in detail in official histories.”

Growing Horns

The Izumo fudoki, a collection of local reports compiled in 733 in what is now Shimane Prefecture, reports that a one-eyed oni devoured a farmer who was plowing a rice field. The Chinese geography text Shan hai jing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) describes the land of the oni with its one-eyed denizens with disheveled hair. This text, originally compiled from the fourth to the third century BC, may have arrived in Japan before the Heian period and influenced the Izumo story.

Koyama says that at least by when the Konjaku monogatari collection of Buddhist tales was completed in the twelfth century, the oni were imagined as having horns. In Jigoku zōshi (Scrolls of Hells) from the end of the same century, various oni appear in illustrations, some red, some blue, and others with the heads of horses or oxen. These colors, their enraged expressions, and their wearing of fundoshi loincloths derive from the gaki (hungry ghosts), yaksha guardian deities, and others in esoteric Buddhism.

“However, it wasn’t the case that all oni in pictures had horns, and there continued to be those without. Also, when ancient or medieval oni attacked humans, they used hammers, and they weren’t drawn with metal clubs until the Edo period [1603–1868].”

The Island of the Oni

A Chinese ceremony for expelling oni that spread disease was carried over into a similar ritual at Heiankyō for driving them out of Japan. This is connected to the Setsubun festival still celebrated today. A ninth-century document records an address read out by a practitioner of onmyōdō at the ceremony. The oni were ordered to go beyond the geographical boundaries of Japan at the time, corresponding today to the island of Sado in the west, Shikoku in the south, Tōhoku in the north, and the Gotō Islands of Nagasaki Prefecture in the west.

The aristocrat Fujiwara no Kanezane wrote in his diary in 1172 about creatures resembling oni arriving by boat in Izu. Inability to communicate led to fighting and considerable injuries among the islanders before the interlopers left. He wrote that a provincial governor had submitted a report of the incident to the imperial court. Kanezane himself was of the opinion that the oni were actually a group of foreigners. The way the Japanese saw foreign people with a different language and appearance as oni shows how much they feared them.

From the medieval to early modern period, Japanese maps included a land called Rasetsukoku, its name deriving from raksasa, the Sanskrit word for oni—this was the island of the oni, now commonly known as Onigashima. One of the models for various legends about Momotarō’s conquest of the oni from around the later medieval to the early modern period is Hogen monogatari (The Tale of Hogen) (1219–22), depicting the exploits of the warrior Minamoto no Tametomo. He landed on an unknown island and forced into submission the ōwarawa, descendants of the oni who were more than three meters high, carried swords under their right arms, and had long, straggling hair.

Until the medieval period, men who did not wear hats or tie their hair were called ōwarawa or dōji, words meaning “child,” even if they were adults. Although they were subject to prejudice based on their low rank, they were also feared for their occult powers. Prominent examples include Ushikaiwarawa, who could handle ferocious oxen, and Dōdōji, who looked after the key to a hall of important Buddhist statues. In The Tale of Hogen and the later Shuten Dōji, the dōji with supernatural powers are connected to oni.

Shuten Dōji (second from right) is a giant dōji by day, but transforms into an oni at night. From the Ōeyama Shuten Dōji emakimono (Ōeyama Shuten Dōji Picture Scroll). (Courtesy National Diet Library Digital Collection)

Connections with Prejudice

Some records described humans giving birth to oni, as babies born with nontypical bodies were called onigo (oni children). Such births were regarded as ill omens, so they were seen as needing action by the state. Often, these children were abandoned.

“Through fear of their appearance, parents could say that children who would be difficult to raise were oni and dispose of them with a convenient sense of righteousness. They could claim that these children threatened a crisis not only to themselves but also to the state,” Koyama says.

Women too were increasingly linked to oni as they lost social status. Koyama explains, “From the outset, Buddhism was a misogynistic religion. That aspect didn’t come over to Japan when it first arrived in the country, but from the second half of the ninth century, prejudice against women gradually established itself along with the spread of the patriarchal system.”

The inferiority of women was emphasized, as they were seen as lacking the ability to practice Buddhism, as well as being lascivious and extremely jealous.

“With the change from the Kamakura period [1185–1333] to the Muromachi period [1333–1568], women became associated with oni,” Koyama says. “In nō drama, brought to a peak of accomplishment by Zeami, there are many female oni driven mad by envy. Women were outsiders in a society centered on adult men. At the same time, they had an unmatched importance in that everyone was born from women. This was why it was necessary to suppress them. If they were weak, they would not be seen as oni. And the fear toward disabled children and foreigners meant that they were also viewed as oni.”

Wartime Enemies

In the ancient and early medieval period, oni had a genuinely frightening image, but into the Muromachi period, skepticism grew about their existence, and they began to be talked about like other supernatural beings such as yūrei and yōkai. Many picture scrolls were produced with jocular illustrations of the hyakki yagyō, a night parade of “one hundred” oni or yōkai. The most famous story of battling against oni at this time was centered on Shuten Dōji at the mountain Ōeyama in what is now Kyoto Prefecture (another theory is that it was Mount Ibuki in Shiga Prefecture). Known for his prodigious drinking, he was a human (dōji) during the daytime, but transformed into a fearsome horned oni at night. The story was illustrated in picture scrolls, with the varied appearance of his oni attendants fostering a tendency for absurdity.

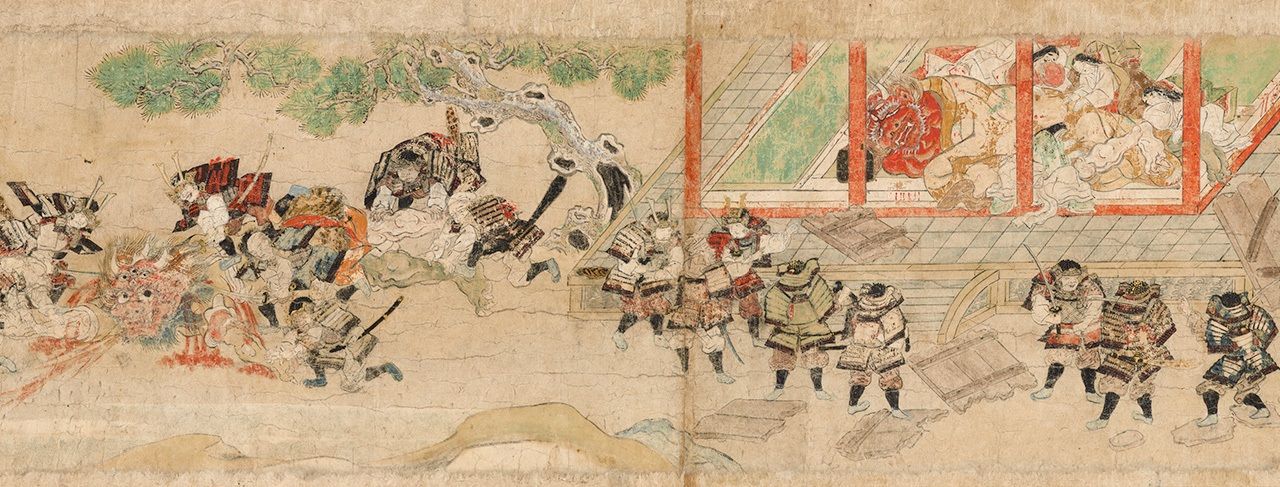

Ōeyama ekotoba (Illustrated Story of Ōeyama) is the oldest extant work depicting the legend of Shuten Dōji, and dates back to the fourteenth century. (Courtesy Itsuō Art Museum)

The Edo period saw a craze for “freak shows,” with a woman described as oni musume, who had a horn-like lump on her head, becoming particularly popular.

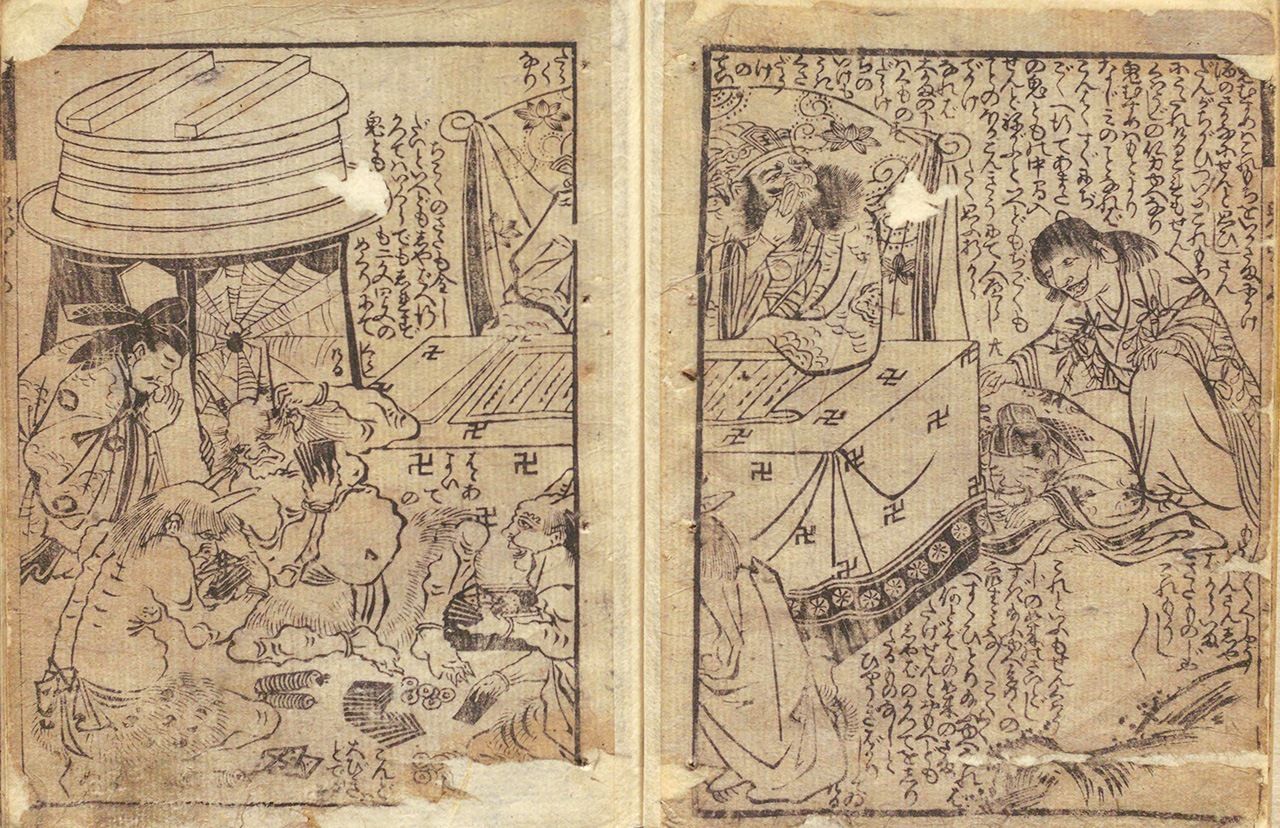

An illustration from an Edo period kibyōshi “yellowback” comic book of King Enma, the ruler of hell, seated at center, with the oni musume (oni girl) to the right, on display in a show at Ryōgoku in Edo (now Tokyo). (Courtesy National Diet Library Digital Collection)

From the Meiji era (1868–1912), oni became associated with war. During the Russo-Japanese War, there were picture books showing Momotarō subjugating Russian oni, while in World War II, US and British soldiers were represented as oni. In Japan’s first full-length animation, Momotarō: Umi no shinpei (Momotarō’s Divine Sea Warriors), released in April 1945, the oni on Onigashima are depicted simply as Westerners with single horns.

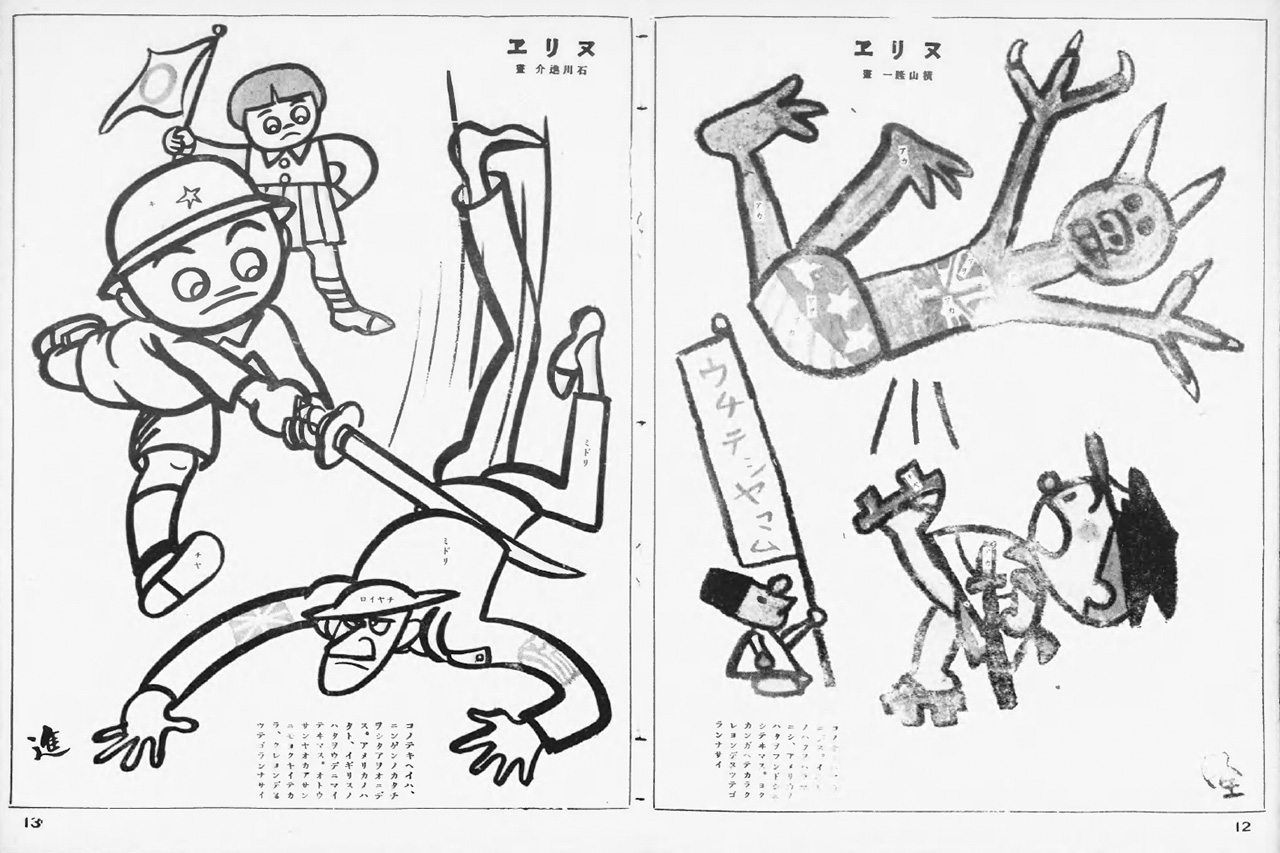

Fuku-chan was a character from a newspaper manga series enlisted into the oni fight. Koyama says, “If young readers saw the mischievous boy Fuku-chan kicking the oni and nobody got angry with him, the creatures [representing Western enemies] must really be bad. It was a clever use of oni to try and unify people to say, ‘let’s conquer them together.’”

Fuku-chan, at right, defeats an oni, while another child slashes an oni disguised as an enemy solder at left. From the wartime propaganda magazine Shashin shūhō (The Weekly Photographic Bulletin). (Courtesy National Archives of Japan).

Remember History

Today oni are familiar as a kind of yōkai appearing in games and stories. There are humorous red and blue oni in the Yōkai Watch series, while the oni (demons) in the social phenomenon Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba have varied appearances and personalities, and are very different from their counterparts in folk tales.

It is fine to enjoy oni as interesting characters, but Koyama says we should not forget their negative history. “From ancient times, the Japanese described their targets for prejudice and exclusion as oni, which were blamed for any kind of national crisis. Using the label of oni carried a fixed image, which shut down any thought of other people or situations as being multifaceted. In the current uncertainty about where the world is going, I think we should study the history of oni, and always consider whether we hold any prejudiced viewpoints.”

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimie Itakura of Nippon com. Banner image: Subjugating an oni in Ōeyama ekotoba [Illustrated Story of Ōeyama]. Courtesy Itsuō Art Museum.)