Exploitation and Culture: Heaven and Hell in the Yoshiwara Pleasure Quarters

Guide to Japan Culture Art History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Two Sides of the “Pleasure” Quarters

“The pleasure quarters are something that must never appear in the world again—they are a place and a system that no reasonable person today would ever seek to replicate,” says Tanaka Yūko, a scholar of culture during the Edo period (1603–1868) and professor emeritus at Hōsei University. These were places of sexual exploitation, where women were treated as bonded labor, forced to work as prostitutes to pay off family debts, and were regularly exposed to disease and violence.

At the same time, the Yoshiwara district in Edo (now Tokyo), as one of the pleasure quarters officially licensed by the shogunate, played a foundational role in the culture of the Edo period, bringing many aspects of Japanese culture together into newly creative synthesis for the first time. Tanaka believes it is important to make clear both sides of the historical reality.

Printing and publishing flourished in Yoshiwara. The district was the birthplace of the famous ukiyo-e prints of Kitagawa Utamaro, produced by Tsutaya Jūzaburō (a publisher who rose to fame through his guidebooks to the pleasure quarters), popular fiction known as sharebon, parodic poetry, and pictorial art, as well as serving as a major center for calligraphy, waka and haiku poetry, the tea ceremony, music and dance, and kimono and other kinds of fashion. It was a place where celebrations and popular events to mark the seasons and other aspects of traditional culture were passed down and refined. Yoshiwara was a zone of entertainment whose offerings and impact went far beyond the sybaritic pleasures of the brothels.

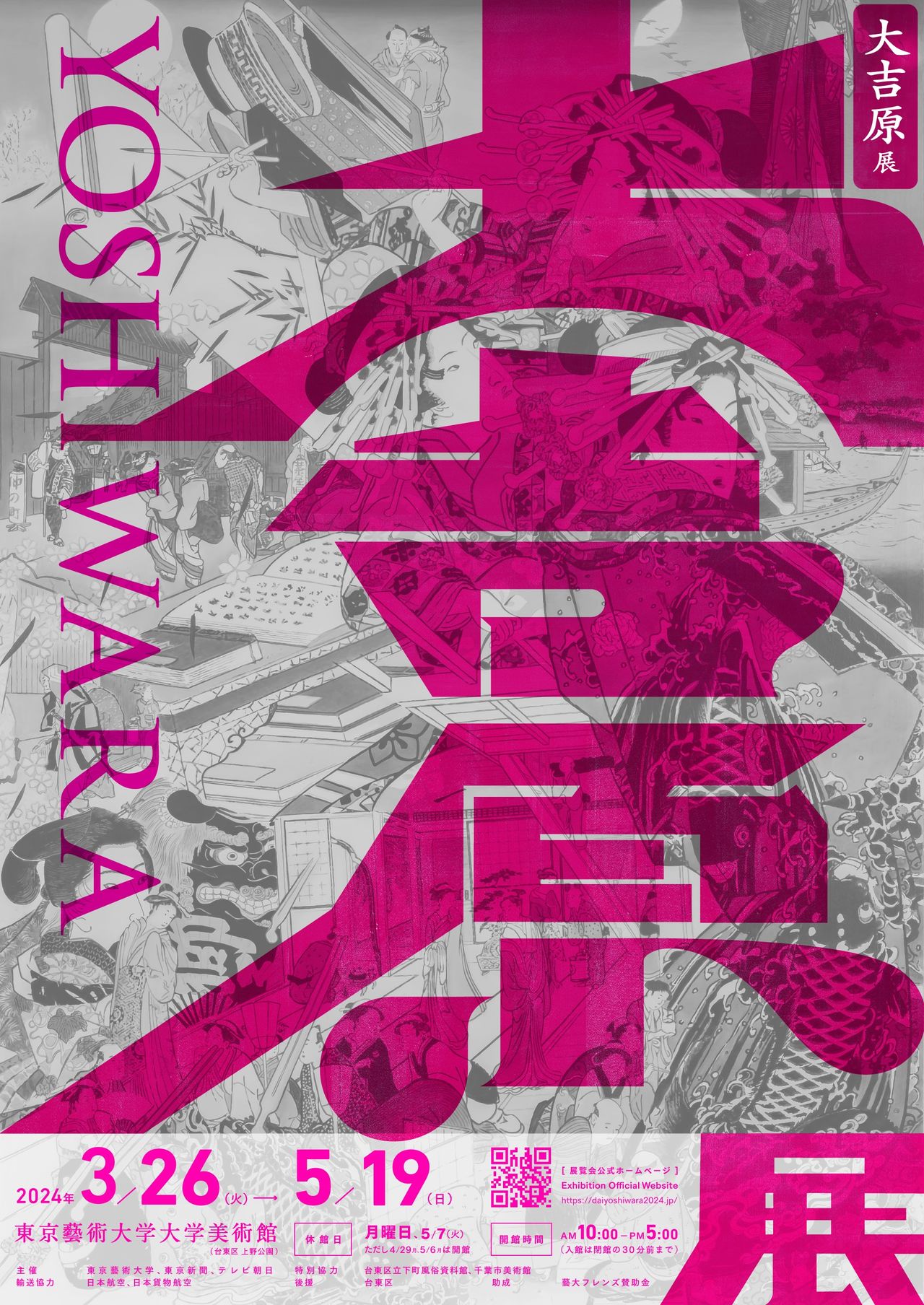

This dual nature today presents a dilemma for anyone wishing to communicate the culture of Yoshiwara. A major exhibition on the culture of the pleasure quarters, for which Tanaka helped as academic advisor, is being held at the University Art Museum (Tokyo University of the Arts) until May 19. Before its March opening, it faced criticism online for ignoring the negative aspects of the district and presenting what went on there as mere “entertainment.” We spoke with Tanaka to learn more about the background and intentions behind the exhibition.

Yoshiwara as Performative Space

“In the past,” Tanaka says, “many exhibitions have focused on the work of ukiyo-e artists, from Kitagawa Utamaro to Chōbunsai Eishi. But this is the first exhibition to examine Yoshiwara itself, and to turn the spotlight on this remarkable space that existed for so long and has now been lost to us forever.”

The pleasure quarters of Yoshiwara (located in what is now Taitō, not far from Asakusa and the famous Sensōji temple) once covered a district of some 100,000 square meters: “a fictional world in which extravagant fantasies of a garish alternative to the everyday world were created and performed” for nearly 250 years, says Tanaka. It provided the setting for the popular manga Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba, and today the history of the area is drawing attention for its tourist potential, although little remains from the height of the district’s fame during the Edo period.

“The focus of the exhibition is on Yoshiwara as a place and how it would have looked and felt at the time. This was a manmade district built in the early decades of the Edo period, with roads laid out on a grid pattern in the middle of the fields just outside the main city. It was home to some of the most impressive buildings that anyone at the time would ever have seen, as well as neat lines of cherry trees and other seasonal flowers along the broad avenue that stretched through the middle of the district.”

Men who came to visit the brothels were not the only people drawn to the district. Women and children came to admire the cherry blossoms, and tourists from out of town came to gawp at the famous sights. The whole district was a melting pot where all aspects of culture came together in a concentrated area, in the context of this remarkable performative space that was perhaps unique in world history. The displays in this exhibition have been designed to communicate the atmosphere and feel of this remarkable place as much as possible.”

The Dignity of the Grand Oiran

“Many of the exhibition pictures depict a vibrant and energetic place of entertainment. Looking at them, it’s almost as if you were there yourself. They bring to life in vivid detail the sights and sounds of people’s conversations, the twang of shamisens, singing and dancing, and parties in full swing,” Tanaka says.

“The artists took great care with details like the patterns on the women’s kimonos, the way they wore their clothes in layers, the balance between their elaborate hairdos and the hairpins and other accoutrements they wore. They brought out the women’s sense of style. Seeing the elaborate ways in which the courtesans adorned themselves helps us to understand how the tailors, dressmakers, and other craftsmen of the time used all their skills and ingenuity in creation.”

What the ukiyo-e artists were interested in capturing in their pictures was not a caricature of the women’s features or a realistic depiction of their naked bodies. “I hope that visitors to the exhibition will get a sense for how the artists worked to capture a sense of the dignity of the women who worked in the pleasure quarters,” Tanaka says. “Relatively early in the Edo period, Ihara Saikaku [1642–1693], a haiku poet and author of vivid prose narratives set in the pleasure quarters of Osaka, used evocative language to depict the resolute women who worked in the brothels. In a slightly later period, the ukiyo-e artists of Edo gave expression to their own esthetic by depicting the dignity of the courtesans in their pictures.”

At left, Chōbunsai Eishi, Yatsushi rokkasen (A Casual Selection of Six Flowers) ca. 1796–98 (© The Trustees of the British Museum); at right, one of a series of pictures depicting the seven great oiran courtesans of the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters by Keisai Eisen, ca. 1818–30. (Courtesy Hagi Uragami Museum, Yamaguchi Prefecture)

The women were ranked according to a strict hierarchy, with privileges and sumptuary regulations governing their dress and conduct. The superstars of the district were the oiran. As the pinnacle of the system, these women were required to have not only physical beauty and exquisite taste in dress and the arts but were also expected to be adept at the shamisen and other musical instruments, and to be trained in the tea ceremony, flower-arranging, and the other elegant pastimes. They were idealized as the perfect women with all the skills to entertain and satisfy the politically and economically powerful men of the times. “It’s quite likely that the women themselves strove consciously to approach as close to that idealized image as possible.”

Kitagawa Utamaro, Nōryō bijinzu (A Beauty Enjoying the Cool), ca. 1794–95. (Courtesy Chiba City Museum of Art)

Birthplace of Modern Publishing

Licensed brothels and pleasure quarters also existed in Kyoto, Osaka, and other cities. The quarters in Osaka provided the setting for works by Saikaku, including Kōshoku ichidai otoko (trans. by Hamada Kenji as The Life of an Amorous Man). But throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was the Yoshiwara district in Edo that had the closest connection to the literary arts.

“The pleasure quarters gave birth to new literary works and even whole genres. Among those who frequented the district were people like Santō Kyōden, a writer of popular fiction that depicted the life of ordinary people and the burgeoning urban culture of the times. The publishing companies of Tsutaya Jūzaburō and others like him created a wide network that linked all kinds of people across genres,” Tanaka says.

“Ukiyo-e artists and writers would meet, become friends and cooperate on new works. The printers, artists, and other craftsmen involved in producing woodblock prints would also form connections through the publisher. The Tsutaya publishing business was located just in front of the main gate into the quarter, and it is easy to imagine how it must have served as the ideal site for networking among the various kinds of people involved in publishing and the arts.”

Utagawa Kunisada, Seirō yūkaku shōka no zu (Picture of the Upper Floor of a Brothel), 1813. (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Glimpses of Daily Life

Yoshiwara and its denizens went to great lengths to mark important events throughout the year. During the Obon festival of the dead in mid-summer, for example, lanterns decorated by famous artists and calligraphers were hung from the teahouses that served as houses of assignation, transforming the whole district into a kind of open-air museum.

During the Niwaka Festival, which took place through the eighth month of the lunar calendar, visitors enjoyed performances of dance and music by male and female geisha on special floats.

“Floats would be carried in a procession down the street through the center of the district, and anyone could see the spectacle of musical and dance performances by the best entertainers from among the Yoshiwara geisha,” Tanaka says.

The most colorful and splendid celebrations of all took place during cherry blossom season. Cherry trees were transplanted just before they flowered, their roots still attached, into flowerbeds that lined the central Nakanochō street of the district, and were removed again once the petals fell. This magnificent spectacle was a tribute to the highly sophisticated skills of the gardeners and horticulturists of Edo period Japan.

Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara, on loan for the exhibition from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Harford, Connecticut, is one of the largest of all the paintings Utamaro created by his own hand (as opposed to prints). The picture shows 52 women of the quarter enjoying the spectacle of the cherry blossoms in full bloom.

Kitagawa Utamaro, Yoshiwara no hana (Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara), ca. 1793. (Courtesy Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

But Furuta Ryō, a professor at the museum who curated the exhibition, says he hopes visitors will enjoy its overall flow, rather than focusing solely on any single masterpiece. “Our hope is that visitors will get a sense of the changing seasons and the way in which the district was lit up by events throughout the year,” he says.

Furuta says he himself was struck by changes in the lines of cherry trees planted along the major roads of Yoshiwara. “Up to a certain time, the trees were planted more or less randomly in front of the teahouses, but then—and it’s hard to be sure exactly when—the practice shifted, and people started placing them in neat straight lines along the Nakanochō street through the center of the district. The change is not mentioned in any of the records we have.”

“Based on the artworks brought together for this exhibition, it seems likely that this change took place around the same time as Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara was painted, in 1793, the fifth year of the Kansei era [1789–1801]. The pleasure district was self-governing, and presumably an agreement was reached within the community as a whole. It seems likely that this colorful line of beautiful cherry trees along the central road of the district must have been introduced during the Kansei era, more or less at the same time as people like Tsutaya Jūzaburō and Utamaro were active.”

Furuta says Yoshiwara and the systems that governed life in the quarter underwent considerable changes over the course of its 250-year history, but that few materials survive that would allow modern scholars to follow the trajectory of these changes. “That is why we wanted to use these works of art to rediscover a lost world that can never be brought back again in reality.”

A Realistic Portrait of a Courtesan

Standing at the pinnacle of the Yoshiwara hierarchy were the oiran, exclusive beauties skilled in all the elegant arts. What kind of people were these champions of the pleasure quarters?

“There are no historical resources that give us a true picture,” Furuta says. “Guides to the pleasure quarters like the Yūjo hyōbanki (a sort of Who’s Who ranking of the women who worked in the district) might note that such-and-such a woman has a particular skill or writes attractive calligraphy, for example, but they do not tell us anything about the women’s personalities. And ukiyo-e pictures are generally marked by the style of the individual artist—all the women in Utamaro’s pictures are depicted in a style that is immediately recognizable as by him, for example. Because of this, we cannot turn to these artworks either for a true picture of what the women really looked like. This is one reason why the pictures would always carry the name of the oiran and the house where she worked. Perhaps in the West, people might have expected the artist to depict the women more faithfully. At least draw her so we can tell who it is supposed to be! But realism in that sense wasn’t a priority for ukiyo-e artists.”

A vivid contrast with the famous ukiyo-e pictures can be seen in the painting Oiran by Takahashi Yuichi, made in 1872, in the early years of the Meiji era (1868–1912).

At left, Takahashi Yuichi, Oiran (Grand Courtesan), 1872, (Courtesy Tokyo University of the Arts); the ukiyo-e print on the right by Ochiai Yoshiiku is a depiction of the same woman, and dates from just three years earlier. (Courtesy Hagi Uragami Museum, Yamaguchi Prefecture)

“This was the first painting that depicted a woman from the pleasure quarters in oils. It is a portrait of an oiran from the Inamoto house, known as the fourth Koina. According to an article in the Tōkyō Nichinichi Shimbun at the time, the painting was commissioned by a frequenter of the pleasure quarters who wanted a painting that would immortalize the authentic appearance of an oiran and preserve the fleeting beauty of the district against the passing of time,” Furuta explains.

“It was probably a deliberate decision to have the woman style her hair in the sagegami hairstyle, which was already fading from the pleasure quarters at the time. Also, her hair is not quite perfect. This is typical of Takahashi Yuichi’s style. He liked to paint things that were slightly off, or just a little out of place. This was an important part of his realism.”

The courtesan is depicted with a stern expression, a hint of exhaustion on her features. A student of Takahashi’s records that the subject of the picture was brought to tears by the finished portrait, protesting angrily: “I don’t look like that. That’s not my face at all!”

Women’s Rights Then and Now

In October 1872, six months after Takahashi painted his portrait, the newly established Meiji government passed the shōgi kaihō rei or “prostitute liberation ordinance,” partly in response to criticism from western countries of the practice of human trafficking. This did not mean that the brothels disappeared: but the women were now understood to be working of their free will, and could no longer be sold into prostitution to pay off debts. But Yoshiwara’s days were numbered, and much of the culture of the pleasure quarters was lost in the years that followed, as values changed quickly and dramatically as a result of increasing westernization.

“The harsh reality for the women in the brothels is not something we should forget,” Furuta says. “Such a system would be unimaginable from the vantage point of our values today. With that in mind, our aim in this exhibition is to communicate the history of Yoshiwara as a place for disseminating Edo culture to the wider Japanese population. That this distinctive space of fantasy and make-believe survived for 250 years is testimony to the vast creative energy on the part of all the various people who congregated here and made this cultural flowering possible.”

Meanwhile, Tanaka stresses that there are two important facts that need to be included in any attempt to communicate the history Yoshiwara and the culture of the pleasure quarters.

Yoshiwara, she says, was a performative space that made skilled use of artistic techniques of every kind. The publishing industry flourished through spreading this culture to the wider society outside The ukiyo-e woodblock prints that are known and appreciated around the world today were born from this environment. This is one fact.

At the same time, the pleasure quarters would never have functioned without the presence there of young women forced into prostitution to pay off debts. Although the shogunate took steps to safeguard law and order in the licensed quarters, they did not protect the human rights of the women who worked there. Until the Meiji era, the concept of human rights itself did not exist, and we cannot legitimize or take at face value the cultural productions of a time without such an idea.

“On the flip side, though, we might ask ourselves whether women’s rights are truly protected in an unequal society, so riven by vast disparities of wealth and opportunity as the one we see in Japan today. I want to use this exhibition to convey my own message about women’s rights. As well as providing an opportunity to learn about a unique place that served as a foundational crucible for Japanese culture, I hope that it will also help to spark a new awareness among people of the many challenges we still face today.”

(Based on an article written in Japanese by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Kitagawa Utamaro, Yoshiwara no hana (Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara) (detail), ca. 1793. Courtesy Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund.)