Onigiri: The Evolving Face of Japan’s Beloved Rice Ball

Food and Drink Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Iconic Dish

Onigiri is perhaps the most characteristic and beloved of all rice dishes in Japan. Simple and versatile, it consists of just a handful of rice pressed together with any number of flavorings or fillings. The ancient food continues to change and evolve, and as Japanese consumers reconsider the meaning of rice amid skyrocketing prices and other changes to the staple grain, I want to shine a spotlight on the history and future of the humble rice ball.

There is no clear record of when onigiri first emerged, but the archeological record suggests that people began pressing cooked rice into a firm shape not long after wet-field rice cultivation became established in Japan during the prehistoric Yayoi period.

Triangular lumps of carbonized rice have been unearthed at the Sugitani Chanobatake Ruins, a mid-Yayoi site in Nakanoto, Ishikawa Prefecture. Rather than being shaped after cooking, though, the rice was steamed in a wrapping in a method similar to modern chimaki, a dumpling of rice steamed in a bamboo leaf.

An ancient onigiri unearthed at the Sugitani Chanobatake Ruins. (© Nakamura Yūsuke)

Experts are divided over whether the rice balls were some kind of portable ration or a special offering for a rite or festival. Rather than wrestle with such questions, though, I want to draw attention to the fact that from extremely early times, inhabitants of Japan were hand-shaping rice into easy-to-eat bundles.

The earliest reference to onigiri in the written record is found in the ancient text Hitachi no kuni fudoki, which depicts life in what today is Ibaraki Prefecture. Compiled around 721, it describes people carrying food with them as they go about their day, including pressed or hand-formed rice called “nigiri ii” from the province of Tsukuba. At the very least, this is proof that forming rice, carrying it around, and distributing it was a part of daily life as early as the eighth century.

The first mention of something recognizable as onigiri comes from the eleventh-century classic, The Tale of Genji. Considered the world’s first novel, it talks about a food called “tonjiki,” which were small, hand-formed bundles of rice that were eaten while on the move or between court ceremonies.

Changing Names

The old name for formed rice bundles, nigiri ii, shifted over time to become nigiri meshi, with both words using the same kanji (握飯). At some point, meshi was dropped and the honorific o prefix was added, producing the modern naming, onigiri.

Alternatives to nigiri meshi to describe hand-formed rice also emerged, such as the word musubi, which came into wide use during the Edo period (1603–1868). The term appears in works like the Morisada mankō, a manual of manners (the book claims the word was originally used solely by women). Again, the honorific o was added later to make omusubi, which is commonly used today alongside onigiri.

Musubi, which derives from the verb “to bind” (musubu), conveys a much wider range of senses than its modern meaning that can be traced back to its roots in the eighth-century Kojiki and Nihonshoki, two of the oldest records of Japanese history. The works describe musuhi, the divine spirit of creation that is the genesis of all things. The word later took on a meaning of something that creates, connects, and bonds together.

Of course, it is hard to draw a direct link between the word omusubi and the divine. However, looking at the layers of mean ing behind the word certainly evokes a special kind of meaning beyond a practical, everyday food that nourishes so many people.

The Taste of Community

Rice farming at its core is a communal endeavor. Filling rice paddies with water requires maintaining and distributing the water supply of a whole community, and planting and harvesting similarly take cooperation.

A ripening rice paddy. Japanese culture is deeply rooted in rice farming. (© Nakamura Yūsuke)

Onigiri is one of the simplest ways to share the rice that comes from such a communal effort. You could describe it as an edible symbol of the community spirit that rice farming entails. In times of disaster or emergency, making and distributing onigiri has become a core aspect of relief efforts, not only because of the ease and efficiency of making rice balls, but also for their perfect suitability for distributing and sharing.

After the 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, volunteers rushed to help supply food to evacuees, and the core dish on offer was onigiri. Rice balls can be made in large quantities with limited ingredients, are easy to carry, and can be distributed with no need for dishes or utensils. All those onigiri, passed from one hand to the next, not only visually illustrated the bonds between people, but also emphasized the power of those bonds. In 2000, an organization dedicated to the preservation and sharing of Japanese food culture named January 17, the date of the earthquake, as Omusubi Day. The group intentionally chose omusubi over onigiri to evoke the bonds between people the food symbolizes.

Land and Sea in One

Onigiri reflects Japan’s geography as a mountainous island nation, with standard fillings like umeboshi, grilled salmon, salted kelp, and bonito flakes representing the bounties of the land and sea. All of these ingredients have long shelf lives and go well with rice. Areas on the coast tend to use seafood or seaweed, while inland and mountainous areas use wild plants, miso, or pickled foods.

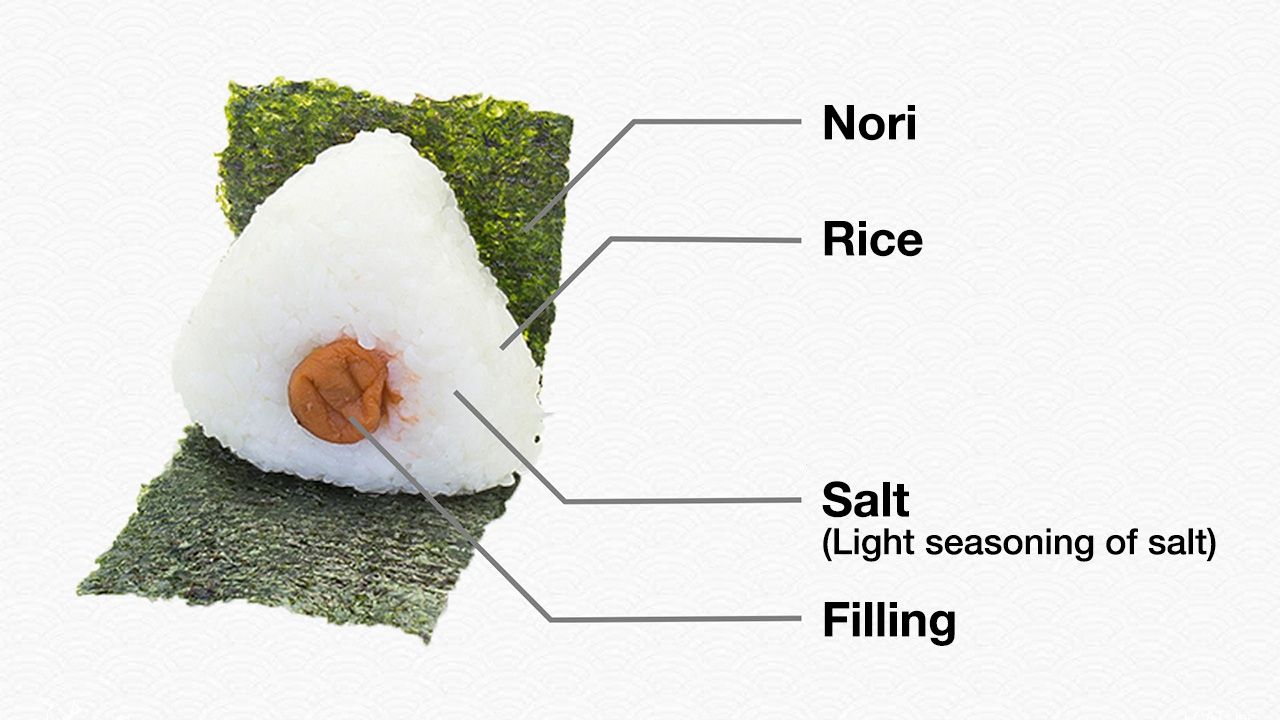

The basic makeup of a rice ball. (© Nakamura Yūsuke)

In its most basic form, onigiri is pressed by hand with a light seasoning of salt for flavor, and then wrapped in nori. However, adding fillings like umeboshi or grilled salmon opens the way for enormous variation. This versatility is a symbol of Japanese food culture itself.

The Japanese diet has changed, and nowadays, no one blinks an eye at onigiri stuffed with modern delicacies like tuna salad, boiled egg, fried chicken, or roast beef. There are standard variations, but onigiri’s flexibility and inclusiveness make it a food without limits.

Why the Triangle?

The shape of onigiri is tied not only to culture, but also logistics and productivity. Rice balls in Japan are by and large triangular, an image that has been reinforced by the ubiquitous convenience store versions. Some say it is a tradition that evokes the shape of mountains, but a more practical argument is that the triangle shape is more stable, helping keep the rice ball from falling apart. In simple terms, the shape is suited for mass production and distribution.

From a historical perspective, though, there is no single onigiri shape. The previously mentioned Morisada mankō states that in the Kyoto and Osaka, the bale-shaped tawara onigiri was most common. In Edo (now Tokyo), onigiri were mostly round or triangular, while other areas produced rice balls that were wide and flat. In recent years, Okinawa’s pork and egg rice ball has established itself as a sandwich-style onigiri. From this, we can see that shape has been dictated as much by the period and convention as consumer tastes and ease of eating.

The four standard shapes of rice balls. (© Nakamura Yūsuke)

Bale-shaped tawara onigiri. (© Pixta)

To respond to rising prices, many onigiri makers are trying to reduce costs by leaving out the nori, but cost is not the only concern. More onigiri have ingredients mixed throughout the ball or, in lieu of a filling, are made from rice cooked with stock and various ingredients or fried rice. Leaving off the nori wrapping allows customers to see what is on offer, letting the onigiri’s attractive visuals whet appetites and encourage buying.

This constant evolution has moved onigiri beyond a fixed traditional food to a dish that keeps step with the times.

Global Recognition

Specialty shops are expanding the possibilities, as well. The Michelin Guide’s Bib Gourmand category, which selects restaurants offering satisfaction beyond their price point, has come to include onigiri shops in recent years.

The increasing international acclaim offered to onigiri shows that it is on its way toward becoming a global cuisine. There are more and more onigiri-focused restaurants overseas, and the Onigiri Society, where I serve as director, is handling more international inquiries.

An array of vibrantly decorated onigiri shows the endless possibilities of the food. (© Nakamura Yūsuke)

In 2024, the Oxford English Dictionary officially included the word onigiri among its terms, giving English speakers a more authentic way to refer to the food aside from the localization “rice ball.”

The versatility of onigiri has helped in its evolution and development, as well as its acceptance overseas even as the traditional heart of “cooked rice shaped by human hands and shared with others” remains unchanged. As the food’s international appeal grows, surely unique interpretations infused with regional flavors will emerge, with every one of these new variations ensuring onigiri a long a vibrant future.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A classic hand-formed triangular onigiri. © Nakamura Yūsuke.)