“Shūkatsu”: How Japanese Students Hunt for Jobs

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

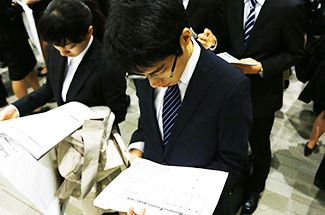

Foreign tourists are now an everyday sight on the streets of Tokyo. One wonders what they make of the young Japanese men and women they see wearing uniform black suits, showing less individuality than even the typical “salaryman.” They are evidently not businesspeople, but what are they? The answer: These are Japanese university students suited up to hunt for post-graduation jobs.

A distinctive feature of Japan’s shūshoku katsudō (job-hunting activity), shūkatsu for short, is that the recruiting schedule at major corporations is set in advance every year based on a consensus among the government, businesses, and academia. The shūkatsu process begins for most students in their junior years, which is when they start attending career seminars at their schools and elsewhere. In their senior years, they submit applications for job openings announced by companies and go through the selection process aimed at winning naitei, promises of postgraduation employment. After graduating in March, they start their new jobs in April, the first month of the fiscal and academic year.

Universities provide their students with information about job openings, hold career seminars, and operate career centers where students can receive individual guidance about finding a job. Through these activities the universities seek to achieve a rapid transformation of their students from “children” who lack essential social know-how into functional “grown-ups.” In that sense, this is a form of education. Since university employees—including people like me, who served as the head of a university’s placement department—generally have no real-life experience working in the business world, schools rely on outside experts to provide guidance. Because of Japan’s low birthrate, universities are competing fiercely for shares of a shrinking pool of prospective students. The job placement results for the students graduating from each university are reported by the media, and good results are a key sales point for the schools, so they give their students considerable support in their job hunts—to the point where some complain that it saps the students’ own initiative.

When they embark on their job hunts, students who were previously passive and careless suddenly start to use polite, respectful language and to exhibit leadership. We teachers are amazed to see this sort of metamorphosis each year. As they transform themselves into “proper” adults, they may be losing something, but in any case they emerge as new Japanese businesspeople in training.

A Revised Shūkatsu Schedule Causes Problems

Every year Keidanren (Japan Business Federation) sets a schedule for the recruitment of graduating students by its members, consisting largely of major corporations. Formerly, companies could undertake recruitment publicity, including the holding of explanatory meetings for junior-year students and solicitation of job applications from them starting in December, and they could interview students from the start of the new school year in April. This meant that students in their senior year were conducting their job hunts while school was in session, and there was concern that this was interfering with their academic work. In response to complaints from universities, the government proposed delaying the process, and after consultations among businesses, Keidanren adopted a new set of guidelines based on the government’s proposal. Under the new rules for the 2016 shūkatsu season (recruitment of students graduating in March 2016), the recruitment publicity season started in March 2015, three months later than previously, and interviewing started in August, during schools’ summer vacation.

In practice, however, this led to problems. The major corporations belonging to Keidanren were bound by the revised guidelines, but non-member foreign affiliates were not, and they snapped up promising students before the big companies started recruiting. Smaller companies not belonging to Keidanren were also free to launch their recruitment drives at an early stage, but they could not match the appeal of foreign affiliates offering prospects of high, merit-based salaries. Furthermore, students tend to prefer the stability of working for a major corporation. So these smaller firms had a hard time snaring recruits.

The extended shūkatsu season ended up causing frustration both among job-hunting seniors, who became fatigued, and among businesses, which were unable to hire as many students as they had hoped. So the guidelines have been modified again. For students graduating in March 2017, the interview season at Keidanren member companies will open in June 2016, two months earlier than last year. But the truth of the matter is that any schedule will have various drawbacks. This is inherent to a system of synchronized recruitment.

A Sellers’ Market for Labor

Japan currently has a sellers’ market for labor. The situation has changed greatly in recent years. The share of nonregular employees has topped 40%, and average incomes have been trending down; meanwhile the low birthrate has led to a severe shortage of workers. This is a serious problem for businesses. And even the administration of Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, which has a conservative image, is working at “promoting the dynamic engagement of all citizens,” such as by bringing more women into the workforce, and relaxing restraints on admission of non-Japanese workers in the aim of increasing the labor supply.

In the present sellers’ market, students who are highly rated by companies have been receiving multiple job offers. This is a headache for corporate personnel departments. Superior students who have received a naitei from one company have no compunctions about backing out if they subsequently get an offer from a company higher on their list. As they put it, “Companies choose among students, so it’s only natural for students to choose among companies”—a self-assured assessment that was rarely heard in the past.

It was in this context that owahara emerged as one of the popular new terms in Japan last year. Short for oware harasumento, or “harassment to end,” it refers to the heavy pressure that some companies have placed on students to halt their job searches after the company has made them an offer. Similar pressure was seen during the bubble-economy years in the late 1980s, but it tended to be petty in nature. For example, if a student visited a company to decline a previously accepted job offer, an employee at the personnel department might intentionally throw some tea on him or her. On a more intense level, some companies had the recipients of their naitei attend prolonged “training” sessions at resorts where they were effectively cut off from outside contact. Today, of course, companies cannot afford that sort of ploy. And if they go too far in applying pressure, students will be quick to spread the word on Twitter and other social media, giving the company a bad name in short order.

How Do Companies Rate Students?

What do companies weigh most heavily when choosing among prospective employees? One factor is the school from which they are graduating, but this is by no means the only consideration. The selection process includes a written test and multiple interviews. In group interviews, corporate recruiters gauge students’ teamwork and leadership abilities, and at a series of individual interviews they observe personality traits and communication skills and look for students’ latent potential. Interviewers focus especially on candidates’ accounts of their failures. They want to know how they have spent their time at school and what they have done to overcome negative experiences. According to recruitment officers, this serves as a basis for assessing whether students have the problem-solving ability they will need in their future work. Some companies also conduct high-pressure interviews where recruiters deliberately take an overbearing approach to see how well the interviewee bears up.

In the face of corporate recruiters, who are specialists in assessing human resources, students will not get far with statements like “I was the deputy head of my club at school, so I have leadership ability.” But how accurately can recruiters hope to assess students’ qualities from short face-to-face sessions? And how can they identify students who have talent but are not good at expressing themselves? Questions like these remain.

How Do Students Rate Companies?

Corporate rankings are published every year showing which companies are most popular among job-hunting students. For the most part, though, these are just indications of how well known the companies are, not actual assessments of them by students. It is presumably in a quest for higher rankings that companies run ads during the shūkatsu season focusing not on their products but on the projection of a favorable image. Top-ranking companies are flooded with hundreds or even thousands of job applications per opening from eager students. With the spread of the Internet, students have been applying to larger numbers of companies. Some say they have applied to 50 or 100. Naturally most of the applications are turned down, and so most students experience repeated rejections. Running into this sort of a setback for the first time in their lives is devastating for considerable numbers of them. So shūkatsu is also a test of students’ mental toughness.

Job-hunting students want to avoid what are called “black companies” in Japan. These are workplaces where, in violation of the Labor Standards Act, employees may be required to put in more than 100 hours of overtime a month, subjected to verbal abuse from bosses, required to meet excessively high targets, or otherwise mistreated. But such workplaces continue to exist. It is not surprising to find harsh conditions like these at companies in fields like information technology that are deluged with work orders and are raking in money or at newly launched start-ups. But students also face the unpleasant reality that getting a job at a “white company” where working conditions are relaxed is no use if the company then goes under.

A Microcosm of Social Change

Meddling by parents in their children’s job hunts can be a headache for both schools and companies. Sometimes parent-child relations are soured by differences over prospective employers. Parents who grew up when the Japanese economy was thriving sometimes force outdated views on their offspring. Members of this earlier generation tend to favor large, well-known companies that promise stability and to be leery of smaller businesses and start-ups. Sometimes students who have won job offers end up turning them down because their parents have expressed doubts, saying, “I’ve never heard of that company; is it okay?” or, “Wouldn’t you be better off at a big, stable corporation?”

It is true that major corporations pay well, offer good benefits, and have strong brands. But even companies that everybody knows have been running into financial trouble. Many students who are truly ambitious have been deliberately setting their sights on little-known small or midsize firms that are developing their business globally or on start-ups in fields like IT and video games. And it is not unusual for students to pick companies based on their values in diverse areas, such as gender and ecology.

One headache for employers these days is the sharp rise in new employee turnover. It is said that 30% of new hires quit within three years. Under the conventional recruitment system at Japanese companies, employees are hired not for their ability to do useful work right away but mainly for their future potential. So companies devote substantial resources to training. And if employees quit after just a few years, this investment cannot be recouped. Apparently it is not unusual for employees who have received a boss’s reprimand for a mistake at work to stop showing up from the following day. Today’s students are less able than their predecessors to cope with failure and scolding, and they despair easily. Middle-aged people complain that the current crop of young employees lack the gumption to stick it out because they were coddled as children. But young people who leave their jobs cite reasons for doing so, including workplace harassment, the desire to lead full lives instead of devoting themselves entirely to work, and the ambition to learn a specialized skill that will allow them to make a living even if their employer goes under.

Some of the characteristics of the salarymen of yesteryear, such as love for the company and a commitment to selfless service, are now historical relics. The system of permanent career-long employment has broken down, and it is no longer uncommon for people to change jobs. The companies that are now leading the growth fields in the economy did not even exist when today’s students were born. Times have changed greatly. The winners among this cohort of students may be those who either find a small and unknown company that becomes tomorrow’s Sony or who are capable of coping with corporate bankruptcies and hopping between jobs.

In shūkatsu we find a microcosm of the changes in Japanese society. Looking at students’ job-hunting activities, we see the decline of formerly popular companies, the change in work styles, and the communication gap between generations. Young people are giving up on and turning away from the material affluence of their parents’ generation. Meanwhile, nonregular employment is on the rise. The number of hikikomori, unemployed social recluses holed up in their rooms, is rising, and they are getting older. All this is happening in the context of a society where people who have wandered off the beaten path have a hard time getting back on to it. There is a shortage of workers, but the labor market continues to lack flexibility. It is no wonder that students worry about their prospects. As they hunt for jobs, students confront the changes in Japan’s economy and the diversification of values.

(Originally published in Japanese on April 28, 2016. Banner photo: Students attend a job fair at the Tokyo Big Sight convention center in March 2016. © Jiji.)▼Further reading

Changing Career Goals for Female Students in Japan Changing Career Goals for Female Students in Japan |  One Look Suits All: Japan, Land of Uniforms One Look Suits All: Japan, Land of Uniforms |  The Words of 2015 The Words of 2015 |  Japan’s Employment System in Transition Japan’s Employment System in Transition |

The Diversity Deficit: How Japanese Corporate Recruitment Has Failed to Move with the Times The Diversity Deficit: How Japanese Corporate Recruitment Has Failed to Move with the Times |  Japanese Women Face Tough Reality in Work and Marriage Japanese Women Face Tough Reality in Work and Marriage |  Higher Education and the Japanese Disease Higher Education and the Japanese Disease |

employment hiring education universities business companies young people generations values

Addressing the Problems with Japan’s Peculiar Employment System

Addressing the Problems with Japan’s Peculiar Employment System  Japan’s Labor Shortages in Perspective

Japan’s Labor Shortages in Perspective  Regular Full-Time Positions Increasingly Elusive for Japanese Workers

Regular Full-Time Positions Increasingly Elusive for Japanese Workers  Shifting the Employment Debate: “Nonregular” Focus Distracts and Misleads

Shifting the Employment Debate: “Nonregular” Focus Distracts and Misleads