“Omikuji” and “Ema”

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

This Year’s Fortune

On hatsumōde, the first shrine or temple visit of the year, Japanese people often draw lots called omikuji that predict whether they will enjoy good or bad fortune in the year ahead. People wishing to know their fate generally pay a fee of around ¥100–¥200. One common method is to select a thin numbered stick from a container and then take a paper fortune from a drawer bearing the corresponding number. Many shrines offer different ways to choose a fortune, with some even having omikuji vending machines.

Drawing omikuji sticks at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture.

Drawing omikuji sticks at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture.

A standard paper fortune will feature a result ranging from daikyō (great bad luck) and kyō (bad luck) to kichi (good luck) and daikichi (great good luck). It will also offer predictions in such areas as health, study, and love and relationships. Traditionally, a good fortune should be taken home. Bad fortunes were once tied to trees in the hope that they would not come true; many shrines and temples now set aside a designated fence-like area for attaching fortunes, though, to avoid damage to the trees.

Tying fortunes at Gokoku Shrine in Hiroshima.

Tying fortunes at Gokoku Shrine in Hiroshima.

Some shrines and temples offer omikuji that concentrate on romantic luck, while others may have English or Chinese fortunes for international visitors, such as Sensōji in Tokyo and Naritasan in Chiba Prefecture. It might also be possible to buy fortunes contained within a simple pottery cat or wooden Daruma doll. This way, even if an unlucky omikuji is left behind at the temple, purchasers have a nice souvenir to take home.

It is said that villagers in the Kamakura period (1185–1333) used to draw lots when at an impasse, such as agreeing on the order to draw water to their rice fields or how to divide fishing grounds. The priest would purify paper lots inscribed with the villagers’ names, picking several out to make decisions. As the gods were considered to be fair, this ensured consensus. By the Edo period (1603–1868), it had become common to ask the gods before making important decisions relating to politics, marriage, or business. This is thought to be the forerunner of today’s omikuji practice.

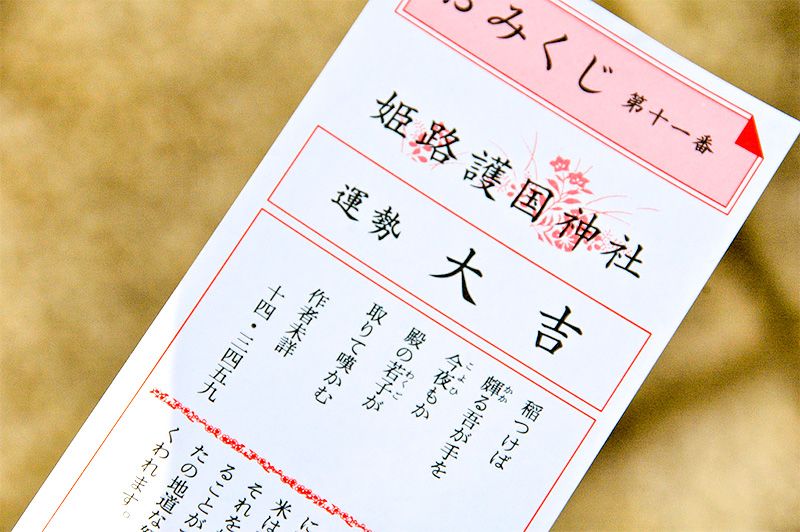

An omikuji predicting daikichi (大吉), great good luck.

An omikuji predicting daikichi (大吉), great good luck.

Wooden Votive Tablets

Visitors also offer up prayers for fortune through the use of votive tablets known as ema. These small wooden plaques are used for various kinds of written prayer. Diligent study is highly touted in Japan, and Yushima Tenmangū Shrine in Tokyo and Dazaifu Tenmangū Shrine in Fukuoka are particularly associated with exam success. In fact, there are some 12,000 Tenmangū shrines around the country, dedicated to the scholar Sugawara no Michizane (845–903), who came to be revered as a deity of learning after his death.

Exam-takers often write 合格祈願 (gōkaku kigan) on their tablets as a “prayer to pass.” Among the various messages used on ema, yojijukugo, or four-character phrases, are quite common. These include 家内安全 (kanai anzen), safety for one’s family; 商売繁盛 (shōbai hanjō), prosperity in business; 健康祈願 (kenkō kigan), a prayer for health; and 恋愛成就 (ren’ai jōju), success in romance. As with exams, different places of worship may be connected with different kinds of fortune and worth making a specific journey.

There are no particular rules for writing on tablets, although it is normal to write prayers on the back rather than the illustrated front side. Some people write their names, but this is not considered necessary. Ema cost from about ¥500 to ¥1,000 and may be either hung in the temple or shrine or taken away to display at home.

Animal Designs

In ancient Japan, it was believed that the gods traveled to the human realms on horses. In the Nara period (710–794) people dedicated horses to temples and shrines. As the practice developed, pictures of horses on wooden tablets were substituted for the real animals. The kanji for ema are 絵馬, meaning “picture” and “horse.”

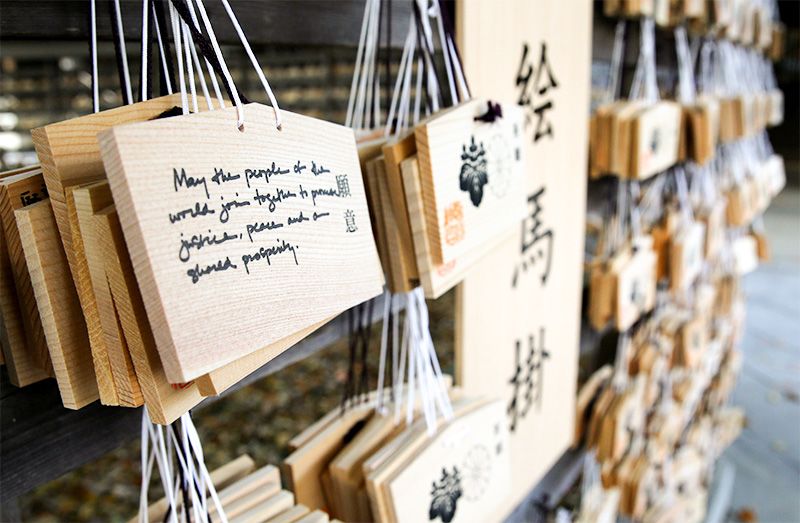

An ema prayer written by US President Barack Obama at Meiji Jingū in Tokyo: "May the people of the world join together to promote justice, peace, and a shared prosperity." © Jiji.

An ema prayer written by US President Barack Obama at Meiji Jingū in Tokyo: "May the people of the world join together to promote justice, peace, and a shared prosperity." © Jiji.

Today, ema designs are not limited to horses, and often have a picture of the year’s eto, or zodiacal animal. The system of associating a different animal with each year in a 12-year cycle came from China during the sixth century. In Japan, the animals (in order) are the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, and boar.

New Year's or before taking a university entrance exam are popular times for making a prayer by ema, but there does not have to be a special occasion. The wooden petitions can be used whenever people feel they need a little assistance from the deities.

Photo credits:Banner photo of ema: Wally GobetzTsurugaoka Hachimangū: clio1789

Gokoku Shrine: GetHiroshima.com

Daikichi omikuji: cotaro70s