Meiji Mura Brings Early Modern Japan to Today

Architecture History Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Historic Building Rescue Project Bears Fruit

Meiji Mura opened in March 1965 in Aichi Prefecture as Japan’s largest open-air museum. The facility gathers and preserves architectural and historical materials from the Meiji era, when the foundations of modern Japan were laid.

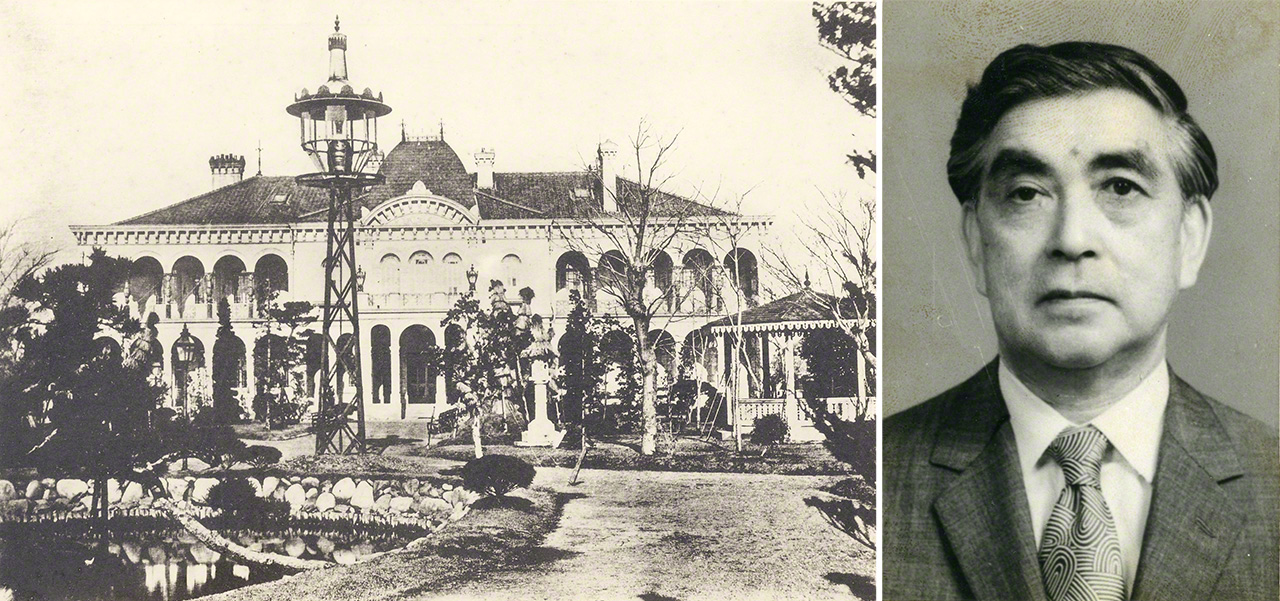

The inspiration for Meiji Mura came when the architect Taniguchi Yoshirō (who would become Meiji Mura’s first head) witnessed the demolition of the Rokumeikan, a cultural symbol of Japan’s opening to the West. Struck with regret by the loss of buildings from the Meiji era, when he himself was born, he developed a desire to preserve examples of Meiji architecture slated for demolition by relocating them and opening them to the public as a gift to future generations.

The Rokumeikan, demolished in 1940, and architect Taniguchi Yoshirō.

Some 20 years after the Rokumeikan’s demolition, at a high school reunion Taniguchi passionately described his desire to preserve Meiji buildings for future generations to friends. One who took his idea on board was Tsuchikawa Motoo, who would go on to serve as president and chairman at Nagoya Railways. Taniguchi and Tsuchikawa began working toward a plan for Meiji Mura that day. When they heard that an outstanding Meiji-era building was scheduled for demolition, historian members of the architectural committee would race to the site like paramedics racing to save a patient.

At the time, they rescued 15 buildings from as far north as Hokkaidō and as far south as Kyoto. They moved the buildings to a 50-hectare plot of land on the banks of Iruka pond in Inuyama, Aichi Prefecture, owned by Nagoya Railways. Landscapers were hired to ensure that the buildings would appear in appropriate settings, and the museum opened on March 18, 1965.

The first guests enter the park at the Meiji Mura opening ceremony.

Rescuing Important Cultural Properties

The work of rescuing Meiji buildings went on after the park opened, and 10 years later, in 1975, it had expanded to cover 100 hectares with over 40 relocated buildings. Japan at the time was in a period of high economic growth, and many old Meiji buildings were in danger of demolition due to projects like road expansion, despite having survived natural disasters and the fires of World War II. Meiji Mura’s unceasing work has helped to make sure they remain to this day.

Currently, 64 buildings have been relocated to the park, and 11 of the buildings now at Meiji Mura are also officially designated as important cultural properties. They cover a wide variety of purposes, including churches, prefectural government buildings, pioneer houses, merchant houses, schools, and lighthouses among the collection. They also come from many places. There are buildings from not only Japan, but Hawai’i, Seattle, Brazil, and other focuses for Japanese emigration. In 1968, when Japan celebrated the “a century of Meiji,” the park saw over 1.5 million visitors. Meiji Mura now works to preserve early modern structures all around Japan to help people rediscover the value of local culture.

Meiji-era architecture scattered across 100 hectares of rolling landscape in Inuyama, Aichi Prefecture.

A Prime Minister Steps In to Save Architectural Heritage

Of all the historical buildings at Meiji Mura, the most popular is the Imperial Hotel Main Lobby. The Imperial Hotel was the work of on the twentieth century’s most important architect, Frank Lloyd Wright. It was completed on September 1, 1923. The Great Kantō Earthquake hit just an hour after the inauguration party, but the building sustained only minor damage and eventually served as a refuge for many victims. The hotel went on to become a common place for guests of state to stay, earning acclaim in Japan and around the world as an example of Wright’s architecture.

However, from the latter half of the 1960s, the hotel struggled to accommodate the ever-increasing number of guests, and the building also began to show signs of age. Despite many calls to preserve it as an important example of twentieth-century architecture, the hotel management decided to demolish it and build a new one. However, in 1967, at a press conference on Prime Minister Satō Eisaku’s return from a Japan-US summit, an American journalist asked what he was going to do about the Imperial Hotel, to which he immediately replied, “I will move it to Meiji Mura.” That set the wheels in motion to move the hotel. This is only the central section of the entryway, but that immediate response from Prime Minister Satō helped preserve a valuable architectural inheritance for future generations.

The central entryway of the Imperial Hotel, built 1923 in Hibiya, Tokyo.

Designed by Wright, an architect celebrated in Japan as the “magician of light,” the interior is composed of bricks and terra cotta fired in Tokoname, Aichi Prefecture, and Ōya stone mined in Tochigi Prefecture. The mood and impressions shift with changes in season, weather, or time.

A view of the Imperial Hotel Main Lobby.

The park has also collected the building where Mori Ōgai and Natsume Sōseki lived in Sendagi, Tokyo, with an eye to passing on the culture of the Meiji era. It is a small, typical Japanese home, but is an important testament to Japan’s literary history; within its walls Ōgai wrote one of his German cycle books, Fumizukai (trans. The Courier), and Sōseki wrote Wagahai wa neko de aru (trans. I Am a Cat) while living there.

The residence where Mori Ōgai and Natsume Sōseki lived, built in 1887 in Tokyo.

Colonial-Style Architecture Brings Taste of Western Influence

Some of the buildings at Meiji Mura are the work of Japanese builders interpreting Western architecture in the colonial style. For example, the Mie Prefectural Government building and Higashi-Yamanashi District Office, both registered important cultural properties, show clear influences of Southeast Asian colonial architecture. Both of these buildings have a veranda across the front designed to shade the rooms from strong direct sunlight. The use of mokume-nuri, a technique to paint a woodgrain pattern onto wood by hand, on the furniture and window frames is another characteristic of the colonial style in Japan, and was inspired by the work of Japanese carpenters on buildings in Yokohama, Tsukiji, and other areas with large non-Japanese settlements. The Higashi-Yamanashi District Office is outstanding for its stucco techniques—particularly around the corners. where they create the impression of stonework despite the wooden construction—and the ceiling done with a traditional Japanese pattern of natural elements, in the style called kachō fūgetsu.

The Mie Prefectural Government building was built in Tsu, Mie Prefecture, in 1879.

The Higashi-Yamanashi District Office was relocated from Yamanashi, Yamanashi Prefecture.

The Saigō Tsugumichi Mansion, a registered important cultural property, with its unusual protruding semicircular balcony, displays strong influences from the former French colony of Louisiana, in the then still relatively new nation of the United States.

The Saigō Tsugumichi Mansion, built 1880 in what is now Meguro, Tokyo. Tsugumichi was the older brother of Saigō Takamori , a famous leader of the Meiji Restoration.

The dining room in the Saigō mansion.

Enchanting Japanese Architecture of the Meiji Era

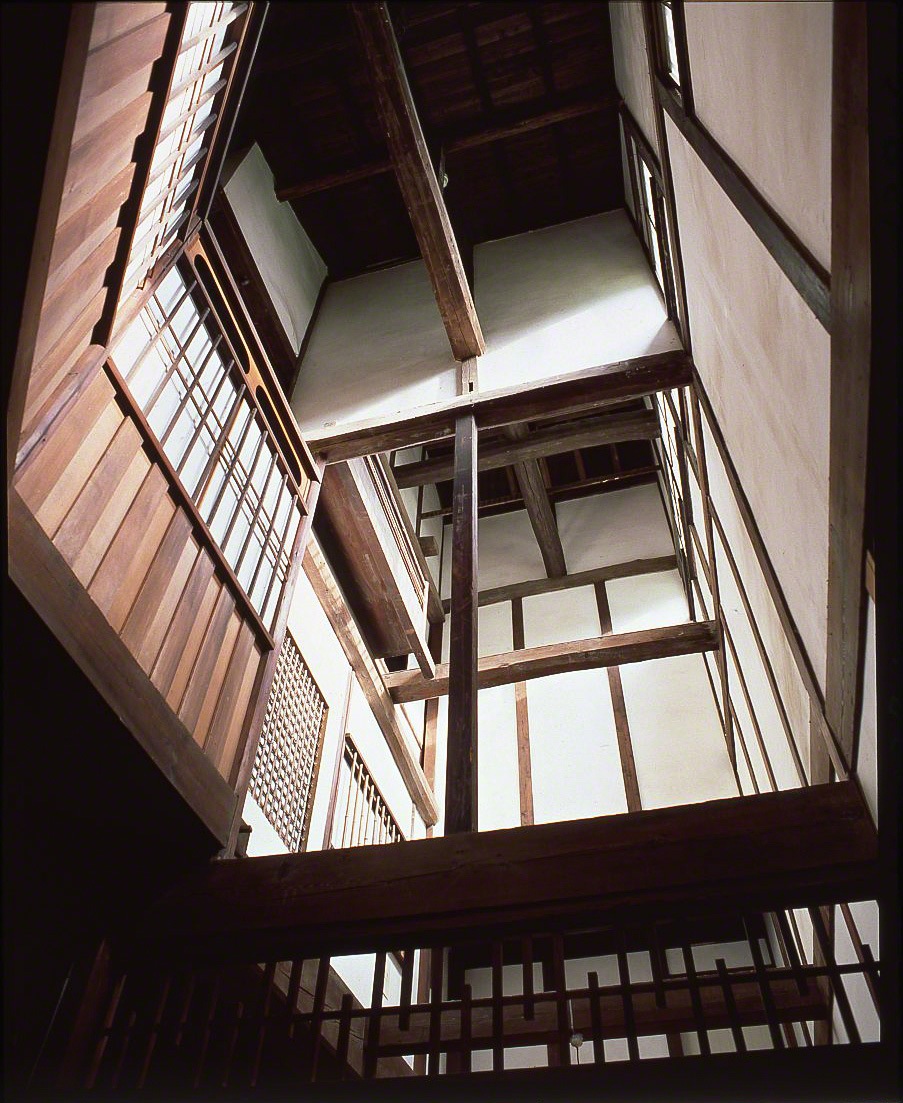

Although Western architecture had a strong influence in the Meiji years, it was also a time when masters of traditional Japanese carpentry reached the peak of their skills. Despite the drab exterior of the Nagoya Tōmatsu Family Residence, another registered important cultural property, one step inside this merchants’ home reveals the very best of such techniques. The building is well suited to Nagoya’s reputation as a traditional tea-ceremony city, with an atrium that extends up to the third floor, a corridor on the second floor that resembles a garden path leading to a tea ceremony room at the end, and a wabi-aesthetic room at the back of the split-level third floor reflecting the tastes of the head of the family. Beyond the arrangements befitting the tea-master’s role, the building stands out for its remarkable combination of refined taste and ingenuity, such as the security measures taken when the owner moved from oil wholesaling to banking, and the lighting and ventilation to enhance the quality of life.

The Tōmatsu Family Residence reached its current state in 1901, after multiple rounds of renovation.

The atrium of the Tōmatsu Family Residence, extending up to the third floor.

Interior Furnishings

In addition to historical buildings, Meiji Mura actively seeks out furniture and other historical materials. It currently has over 30,000 pieces in its collection, some of which are on display inside the buildings. It has furniture and furnishings from the Rokumeikan, Meiji palace, and the Akasaka Palace, and furniture designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, Takeda Goichi, and Endō Arata, in a collection whose size is unparalleled in Japan. Each building’s study and dining room are appropriately furnished, and museum visitors can actually sit down and experience the rooms as they originally were.

At left is a balloon-back chair in a style popular in nineteenth-century Britain, decorated with Japanese decorative cherry blossom makie lacquer patterns, from the Saigō Tsugumichi Mansion; at right is a peacock chair designed by Frank Lloyd Wright on display in the lobby of the Imperial Hotel.

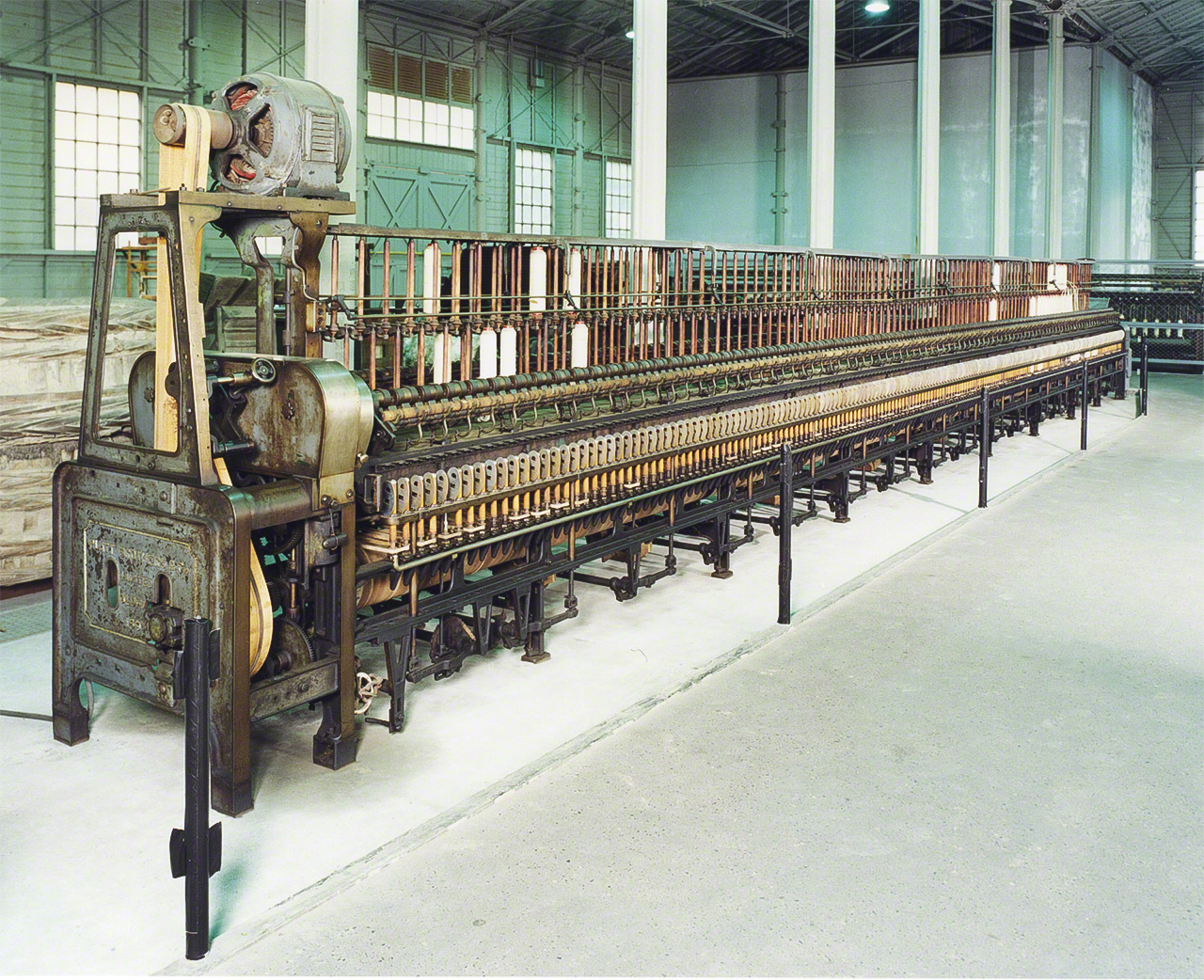

The museum displays machines that helped lay the foundations for modern Japan, including a single-cylinder-type Brunat steam engine, as well as three important cultural properties: a Chrysanthemum Crest planer, a British ring spinner, and an Inokuchi-style centrifugal pump built during the dawn of Japan’s rail era at the National Railways Shinbashi Factory. Volunteer guides are available to activate some and offer demonstrations and explanations.

Ring spinner made by the British company Platt Brothers.

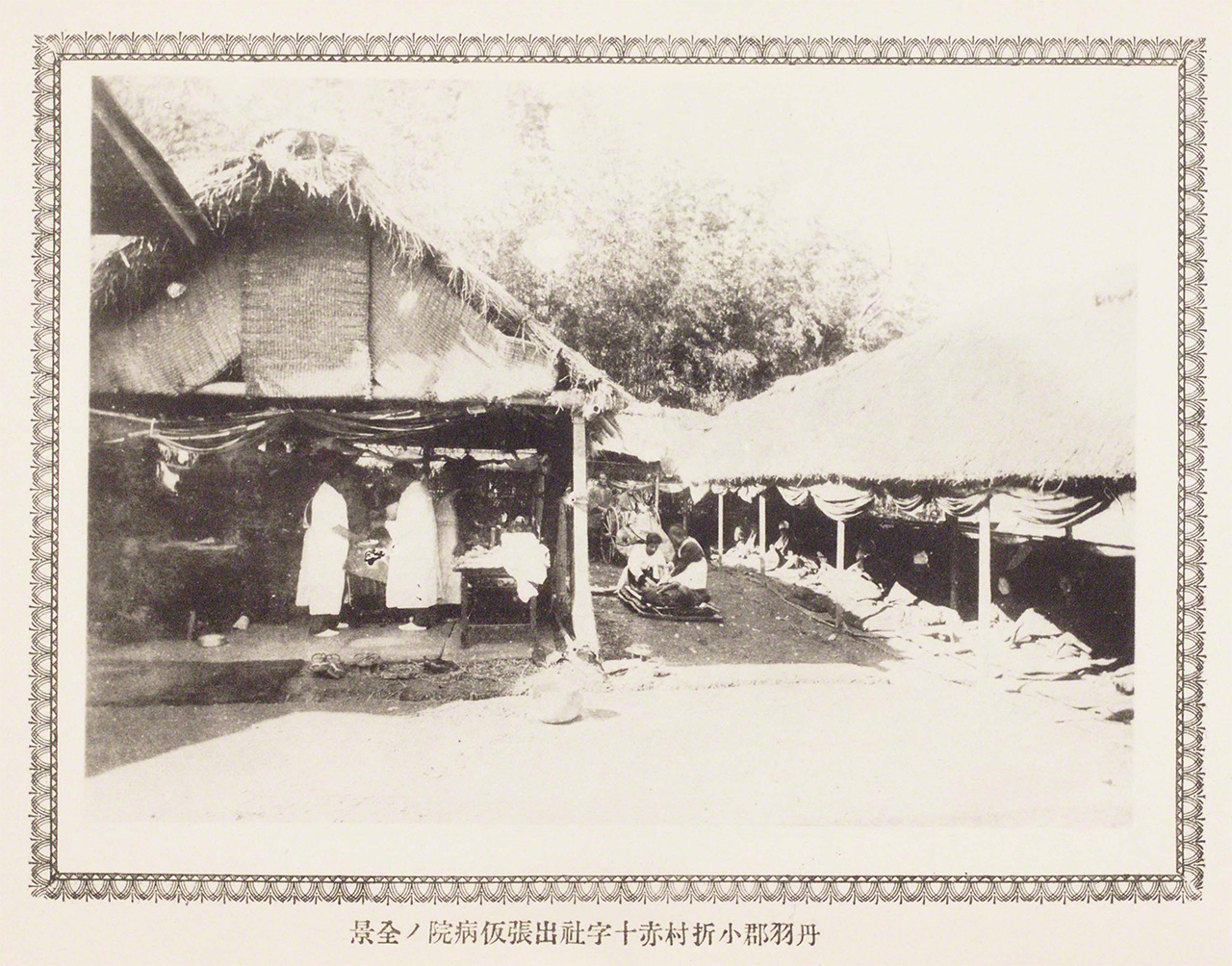

Meiji Mura also has an archive of around 5,000 documents, books, and photographs from the Japanese Red Cross Society, which were rescued from destruction when the society rebuilt its headquarters. They include records of the JRC’s leading disaster relief activities and Japan’s first humanitarian aid activities in aid of Polish orphans, and are a valuable historical record to demonstrate the society’s activities to future generations.

Photographs documenting relief efforts by the Japanese Red Cross Society after the Nōbi earthquake of 1891.

In 2018, the museum used crowdfunding to pay for repairs and restoration of a large American reed organ dating back to 1890. Staff members now play the restored organ, offering the sounds of Meiji to visitors.

The 1890 American organ still produces music today.

A steam locomotive that ran between Shinbashi and Yokohama during the early days of the railroads and Japan’s first city streetcar, the Kyoto City Tram, are also on active display. Visitors can board the cars, where the steam whistle, the billowing smoke, and the rumbling of the streetcar will transport them back to Meiji.

A British Sharp Stewart Steam Locomotive that once ran between Shinbashi and Yokohama.

German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once said that “Architecture is frozen music.” This seems to mean that the beauty of music fades after it is played, while architecture gives that beauty a lasting shape. While all that has a shape must pass, someday, the preservation of these important Meiji era buildings for us is valuable beyond measure for as long as visitors come to enjoy and learn from them.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Meiji Mura scenery. Photographs and videos © Meiji Mura Museum.)

culture architecture museum Meiji Frank Lloyd Wright Aichi Prefecture