Challenging the Myth of the Male Emperor: New Light on the Society of Ancient Japan

Society Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Beginnings

Yoshie Akiko’s love of ancient Japan goes back to her childhood, when she immersed herself in tales of Yamato Takeru and other semi-legendary figures of the protohistoric era. As a university student, she majored in Japanese history, but she never imagined she could go on to become a historian herself. She wanted to contribute something to society, but career opportunities for women were severely limited in those days.

Upon graduating in 1971, Yoshie spent a fruitless year looking for work before marrying at age 23 (about the average at that time). For the next six years, her days were occupied with housekeeping and childrearing. She knew she was doing important work, but it was not enough.

“As much as I loved my family and wanted to be there for them, I began to question the notion that childbirth and childrearing should exclude women from a more public role in society, and I began to think about tackling the issue from a historical perspective. Once my research objectives were clear, I decided to enroll in graduate school.” That was in 1979, a time when feminism was on the rise in Japan, as in other parts of the developed world.

“Women’s history only began to gain recognition as an academic discipline in Japan in the 1980s, amid the spread of feminism and an influx of women scholars,” says Yoshie. “I was one of those women.”

However, as Yoshie stresses, the foundations of her work on women in ancient Japan were laid much earlier.

“Even before World War II,” she notes, “the ethnologist Takamure Itsue [1894–1964] had argued that the customs of visiting marriage and matrilocal residence had prevailed up through the Heian period [794–1185]. It was only much later that patrilocal marriage became the norm. In ancient Japan, children were typically brought up in the households of their maternal relatives, which strengthened matrilateral bonds. Takamure maintained that women held a respected position in ancient Japanese society, not an inferior one. But of course, in those days men completely dominated academia, and they continued to do so after the war, so her theories were largely dismissed.”

Reading Between the Lines

In her own research, Yoshie has attempted to shed light on women’s political role in early ancient Japan through a close reading of ancient texts, including the eighth-century histories Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters), the Nihon shoki (Chronicle of Japan), and the Shoku Nihongi (Chronicle of Japan, Continued); the Man’yōshū poetry anthology (dating to the seventh and eighth centuries); local gazetteers known as fudoki; and Japan’s earliest written laws.

“You find almost no mention of women in Japanese scholarship tracing the development of the Yamato state and ancient government,” says Yoshie. “And source material for the early ancient period is particularly limited. But even the standard sources begin to yield all kinds of previously overlooked clues when you reread them with [women’s] issues in mind. For example, there are references to female village heads and clan chieftains, and we find that women had inheritance rights.”

By the early 2000s, research on women in ancient Japan had begun to attract widespread interest with the publication of several books presenting new findings on the roles of female clan chieftains and emperors. (In this article, the Japanese word tennō, which is gender neutral, is generally translated “emperor.” However, for purposes of clarity, and in keeping with common practice, the title of “Empress” is retained in reference to specific individuals.)

“Women scholars were gradually illuminating the leadership role of women in ancient Japan, and a few male historians were even referencing those findings in their own work. Around the same time, the historical issue of succession to the imperial throne was becoming a hot topic in the mass media owing to mounting concerns that the imperial line would hit a dead end under the current rule of patrilineal male succession.”

Who Was Himiko?

It was also around that time that Yoshie embarked on a major study of Himiko, a figure known to us from an account in the third-century Chinese dynastic history Records of the Three Kingdoms. The record, known to Japanese scholars as the “Gishi Wajin den” (Account of the People of Wa in the Chronicle of Wei), speaks of Himiko as the queen of Yamatai, a country in the land of Wa, meaning Japan. It states that a group of chieftains “jointly installed” Himiko as their ruler to put an end to years of civil war. It also refers to her as a shaman-queen and states that she ruled with the help of her younger brother.

“In Japan, hundreds if not thousands of papers have been written on the subject of Himiko and Yamatai, all based on the “Gishi Wajin den.” A narrow reading of that source has led scholars to the conclusion, which persists even today, that Himiko was a reclusive shaman, and that it was her younger brother who actually governed. No one has seen fit to question the biased assumption that it was naturally a man who held the reins of political power.”

Yoshie believes that the “Gishi Wajin den” must be interpreted in the context of recent archeological and historical findings, on the understanding that the account reflects the biases of ancient China’s strictly patriarchal, patrilineal society. Rereading the text carefully with all this in mind, Yoshie became more and more convinced that Himiko was personally in charge of her country’s government and diplomacy.

For example, one reason historians have minimized Himiko’s political and diplomatic role is that the “Gishi Wajin den” claims she never appeared in person before foreign emissaries. But as Yoshie sees it, her concealment is compelling evidence that she was a ruling monarch. “The Yamato monarchs never showed themselves to outsiders until the late seventh century, when the construction of the Chinese-style Fujiwara Palace created a space for them to hold audiences with foreign emissaries,” she notes.

Archeological analyses of the contents of Japan’s burial mounds, or kofun, suggest that there were women as well as men chieftains up and down the Japanese archipelago, with women making up anywhere from 30% to 50% of the total. Some of these women were buried with weaponry. As Yoshie sees it, Himiko’s “joint installation” as ruler over some 30 such chieftains occurred in the context of a society where women participated in government on an equal footing with men.

According to the “Gishi Wajin-den,” the Wei kingdom conferred on Himiko the title of “Queen of Wa and Friend of Wei”—a testament, in Yoshie’s view, to Himiko’s diplomatic prowess.

Shining a Light on Empress Suiko

Between the end of the sixth century and the third quarter of the eighth century, six women—representing eight separate reigns—ascended to Japan’s imperial throne: Suiko, Kōgyoku/Saimei, Jitō, Genmei, Genshō, and Kōken/Shōtoku. In fact, women accounted for roughly half of the emperors during this crucial period in the early history of Japan and the imperial court. Yet historians have treated them as if they were just “transitional heirs,” drafted on an ad hoc basis to prevent a break in the male line.

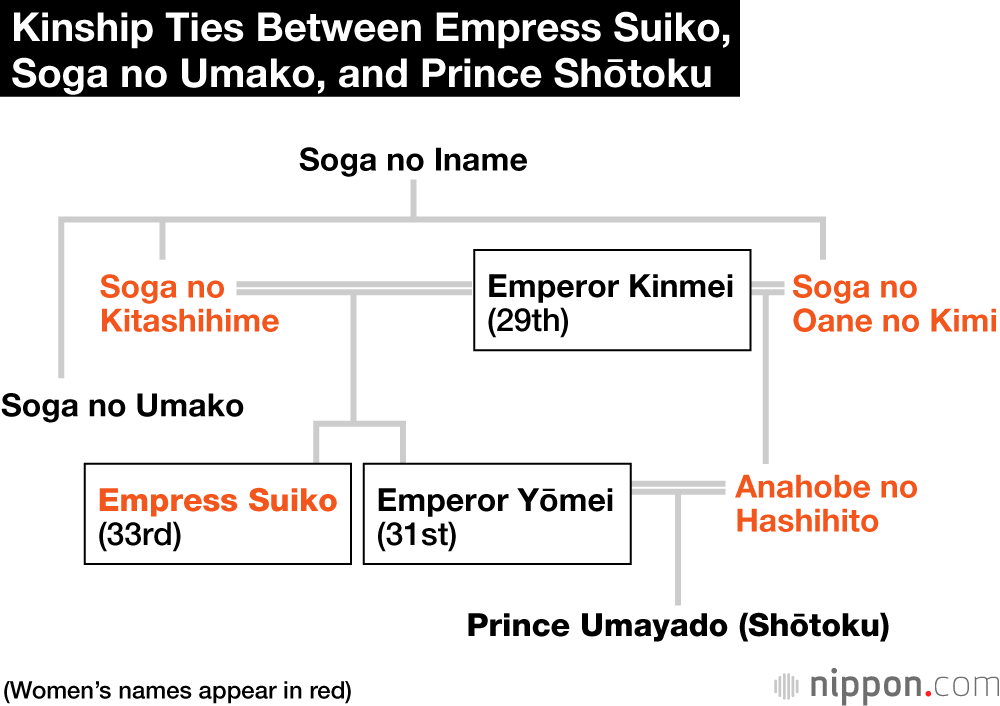

Yoshie feels that history has been particularly unfair to the first of these, Empress Suiko (r. 592–628). The daughter of Emperor Kinmei and Soga no Kitashihime, of the powerful Soga clan, Suiko reigned for a full 36 years, a period that saw important progress in the enterprise of nation building, supported by the introduction of Buddhism. Yet credit for those achievements tends to go to Suiko’s uncle, Soga no Umako, and to her nephew, the regent Prince Shōtoku (574–622). According to Yoshie, this is partly a result of biases written into the Chronicle of Japan, the official history that constitutes our main source for the period from the late 500s to the early eighth century.

“The deification of Prince Shōtoku began around the time the Chronicle of Japan was being compiled, so it’s difficult to get a clear picture of Empress Suiko, since she tends to be obscured by that legend,” she says. “But just looking at the undisputed historical facts, it seems clear that Suiko was a true ruler who actively engaged in diplomacy and knew how to make the most of both men’s abilities.”

During this period in history, says Yoshie, the title of king or emperor was conferred on a person whose leadership the heads of the country’s powerful clans could accept—much like Himiko’s “joint installation” several centuries earlier. Yoshie believes that the selection of a leader among eligible heirs was determined less by gender than by age and experience; one had to be close to 40 years old to qualify.

The Chronicle of Japan records that Empress Suiko’s father, feeling he was too young and inexperienced to become emperor at age 31, initially asked the wife of a previous emperor to take the throne in his stead, but she refused. As Yoshie sees it, the account (historical inconsistencies notwithstanding) can be taken as evidence that wisdom and experience were regarded as more important than gender.

“The Yamato court was consolidating its power amid intense competition,” says Yoshie, “and it had even sent troops to the Korean Peninsula, so the monarch had to be someone with the experience and leadership to unite and govern those under her.”

When Empress Suiko took the throne, she was 39 years old; Prince Shōtoku, then known as Umayado, was only around 20. Given the prevailing emphasis on age and experience, it seems unlikely to Yoshie that Prince Shōtoku would have managed affairs of state on Suiko’s behalf. Yoshie also questions the widely held belief that Suiko was essentially the puppet of her powerful uncle, Soga no Umako.

“The uncle and niece were only separated by two years,” she points out. “I’m inclined to view them as intimates from childhood, brought up together in the same matrilocal household of the Soga clan—two equals who shared similar ideas about nation building via the introduction and spread of Buddhism.”

Ancient Japan’s “Bilineal” Society

At one time, historians classified all societies as either patrilineal or matrilineal. But there is growing recognition, supported by cultural anthropology, that ancient Japan was a “bilineal society,” in which the maternal and the paternal lines of descent were valued equally. Both bloodlines factored into an individual’s stature within the clan, and both female and male offspring of the emperor were seen as legitimate heirs to the throne.

“The principle of patrilineality wasn’t codified in Japan until the late seventh century, when the court embraced the Ritsuryō system modeled on the institutions of Tang China. But I believe that bilineality persisted in Japanese society, including the ruling class, up through the eighth century or so,” Yoshie says. She notes that the family tree of Prince Shōtoku as depicted in the Tenjukoku mandala shūchō, dating to 622, clearly reveals an equal emphasis on the male and female lines of descent. The Chronicle of Japan, by contrast, tends to emphasize the male line, reflecting the growing influence of Chinese norms within Japanese officialdom.

Having imperial blood on both the maternal and paternal sides heightened one’s claim to legitimacy, and consanguineous marriage was common among members of the imperial household in the sixth and seventh century. In fact, during this period the majority of emperors, male and female, were related to a previous emperor on both the paternal and maternal sides, going back no more than two generations.

Yoshie notes that both Emperor Jomei (r. 629–41) and his consort, who became Empress Kōgyoku, were related to Emperor Kinmei on their maternal and paternal sides. Their sons—later to become Emperors Tenchi and Tenmu—were still small children when Emperor Jomei died, and their mother acceded to the throne as Empress Kōgyoku (r. 642–5). “Although she briefly abdicated, she was installed again as Empress Saimei [r. 655–61], a testament to her abilities. While her sons were growing up, they doubtless learned from her example as a ruler. From this standpoint, Emperors Tenchi and Tenmu can be seen as examples of matrilineal imperial succession.”

Male Succession Is a Modern Rule

There were also two more female emperors during the Edo period (1603–1868): Empress Meishō (r. 1629–43) and Empress Go-Sakuramachi (r. 1762–71). Yoshie agrees that these two were probably nakatsugi or “transitional heirs,” to use the current terminology, and she speculates that scholars from the 1960s on, extrapolating from those examples, concluded that this had always been the function of female emperors. But Yoshie’s research argues otherwise.

The current rules of imperial succession—in which only a man descended from the male line may succeed to the Chrysanthemum Throne—were first codified in the Imperial House Law of 1889, enacted along with the Meiji Constitution in the context of Japan’s drive to build a modern imperial nation-state.

“There was fierce debate about the rules of succession until the very last, but in the end it was decided that a woman could not ascend to the throne and that succession had to be exclusively patrilineal, from father to son.” The debate was rekindled in the 1990s, amid a dearth of eligible male heirs, and in 2005, a government panel endorsed female succession. But the momentum for reform flagged after a male heir was born to Prince Fumihito and Princess Kiko in 2006.

On paper, at least, Japan abandoned the ie system and other patriarchal institutions after World War II. The postwar Constitution, predicated on the principle of popular sovereignty, assigns the emperor a strictly ceremonial role and accords equal rights to men and women. “Even so, male chauvinism persists in Japanese society,” says Yoshie, “and the imperial household continues to follow rules of succession adopted in the era of imperial sovereignty.”

A big part of the problem, says Yoshie, is that most people in Japan fail to realize that patrilineal male succession is a relatively new system.

“I think a lot of people are opposed to changing the rules in the mistaken belief that male succession has been a sacred tradition from time immemorial. It’s time for the Japanese people to free themselves from this myth and rethink the ‘traditions’ of the imperial household in the context of the emperor’s symbolic role under the Constitution of Japan.”

(Originally written in Japanese by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Idealized portrait of Empress Suiko by Tosa Mitsuyoshi, dated 1726, Eifukuji, Osaka.)

emperor Imperial House Law imperial family history empress Prince Shōtoku