The Japanese Calendar

Culture Lifestyle History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan is said to have drawn up its first calendar in 604. It was a lunar calendar based on the phases of the moon, introduced from China via the Korean Peninsula. Over the centuries, seasonal events and observances have filled out the traditional marking of time.

Japan adopted the solar (Gregorian) calendar in 1873, yet many expressions inherited from the old lunar system are still in use today.

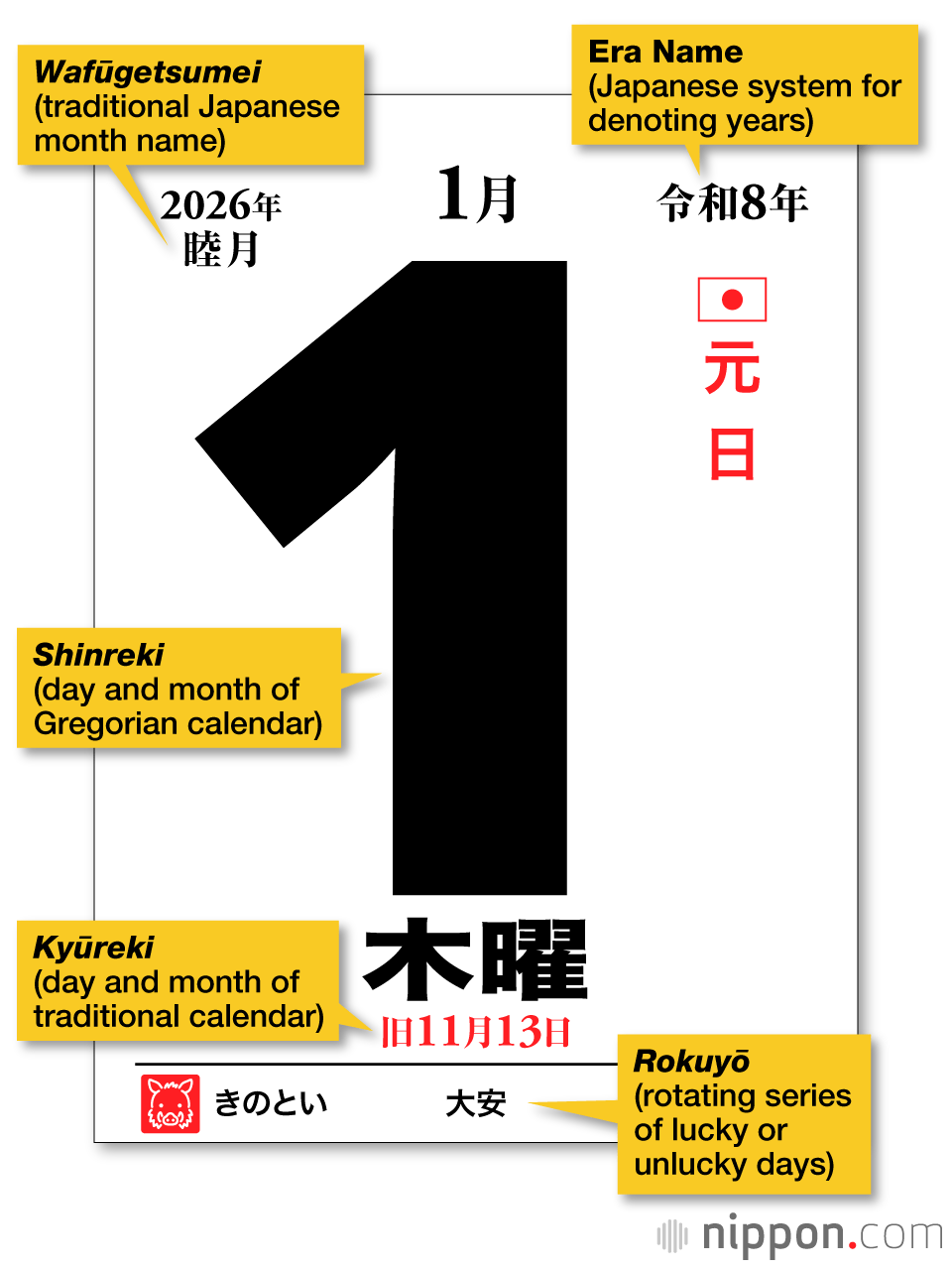

A calendar for January 1, 2026, with several traditional features.

Era Names

Japan uses its own system of era names for denoting years alongside the Western standard. For instance, the year 2025 was also Reiwa 7, the seventh year of the Reiwa era. The first era name was Taika, used from 645 to 650. In earlier times, a new era name might be declared for many reasons—such as to mark a celebration or in response to a disaster. Since 1868, however, new eras have been launched only with the accession of a new emperor.

12 Zodiac Animals

The 12 zodiacal animals form a 12-year cycle. Traditionally, these are called the jūnishi, but in contemporary usage, they are informally known as eto. The system originally came from China and spread through other countries in the region, with slight variations in the animals used.

In Japan, the order is rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, and boar. Illustrations and photographs of the animals are prominent on New Year cards, and they are also used when talking about people’s birth years.

Traditional Names for Months

Each month in Japan’s traditional lunar calendar was given informal, Japanese-style names reflecting the seasons or a major event during that month. These names still appear in some modern calendars today, though the seasonal associations behind the names do not always match the current system.

- 睦月 (Mutsuki)

The month when family members gather for the New Year. - 如月 (Kisaragi)

The month of bundling up against the cold. - 弥生 (Yayoi)

The month of renewed growth of plants. - 卯月 (Uzuki)

The month when deutzias bloom. - 皐月 (Satsuki)

The month of planting rice seedlings. - 水無月 (Minazuki)

The month of water, when farmers flood paddy fields. - 文月 (Fumizuki)

The month when rice ripens. - 葉月 (Hazuki)

The month of falling leaves. - 長月 (Nagatsuki)

The month when nights grow longer. - 神無月 (Kannazuki)

The godless month, when the kami of Japan are said to gather at Izumo Taisha Shrine in Shimane Prefecture. In Izumo, this is called Kamiarizuki, or “the month of gods.” - 霜月 (Shimotsuki)

The month of frost. - 師走 (Shiwasu)

The month when priests run around, making preparations for the New Year.

The Five Sekku

The five sekku are seasonal festivals that take place on days deemed to be auspicious. Each festival is also known by another name that reflects the plant associated with the season.

- January 7: Jinjitsu no Sekku (Nanakusa no Sekku)

People eat nanakusa-gayu (rice porridge with seven spring herbs) at breakfast, wishing for health and protection from illness in the year ahead. - March 3: Jōshi no Sekku (Momo no Sekku)

A celebration for girls, praying for their growth and happiness. Families display hina dolls, giving rise to the Hinamatsuri or Doll Festival. It is associated with peach blossoms. - May 5: Tango no Sekku (Shōbu no Sekku)

Traditionally a celebration for boys, praying for their growth and success. Today, it is a national holiday known as Children’s Day. It is associated with irises. - July 7: Tanabata no Sekku (Sasatake no Sekku)

On this day, people write wishes on colored paper and hang them on bamboo branches. - September 9: Chōyō no Sekku (Kiku no Sekku)

A day to pray for long life and good health. Chrysanthemum petals are floated in sake and enjoyed as part of the celebration.

Dolls on display for Hinamatsuri on March 3. (© Pixta)

The 24 Sekki: Subdivided Seasons

The 24 divisions of the year have traditionally been used to mark seasonal changes. Farmers once referred to these sekki or “solar terms” when planning agricultural activities. Because the system was created in ancient China, some of the terms do not perfectly match Japan’s modern climate. Japan also devised a calendar with each of the 24 sekki divided further into three kō, creating a total of 72 microseasons.

Spring

- February 4: 立春 (Risshun)

Beginning of spring - February 19: 雨水 (Usui)

Rainwater - March 6: 啓蟄 (Keichitsu)

Insects awaken - March 21: 春分 (Shunbun)

Spring equinox - April 5: 清明 (Seimei)

Pure and clear - April 20: 穀雨 (Kokuu)

Grain rains

Summer

- May 5: 立夏 (Rikka)

Beginning of summer - May 21: 小満 (Shōman)

Lesser ripening - June 6: 芒種 (Bōshu)

Grain beards and seeds - June 21: 夏至 (Geshi)

Summer solstice - July 7: 小暑 (Shōsho)

Lesser heat - July 23: 大暑 (Taisho)

Greater heat

Autumn

- August 8: 立秋 (Risshū)

Beginning of autumn - August 23: 処暑 (Shosho)

Manageable heat - September 8: 白露 (Hakuro)

White dew - September 23: 秋分 (Shūbun)

Autumn equinox - October 8: 寒露 (Kanro)

Cold dew - October 23: 霜降 (Sōkō)

Frost falls

Winter

- November 7: 立冬 (Rittō)

Beginning of winter - November 22: 小雪 (Shōsetsu)

Lesser snow. - December 7: 大雪 (Taisetsu)

Greater snow - December 22: 冬至 (Tōji)

Winter solstice - January 5: 小寒 (Shōkan)

Lesser cold - January 20: 大寒 (Daikan)

Greater cold

* Dates indicate the start of each solar term. They may vary slightly from year to year.

Rokuyō: Auspicious and Inauspicious Days

Rokuyō refers to six labels that indicate whether a given day is considered lucky or unlucky. Even today, some calendars still print these designations. Interpretations vary, but the following are the most commonly accepted meanings.

Typical interpretation

- 先勝 (Senshō)

A good day for acting swiftly. The morning is auspicious, but the afternoon is unfavorable, as indicated by the meaning of the characters: “first win.” - 友引 (Tomobiki)

The name of the day indicates that you can “draw friends” into similar kinds of fortune, so it is propitious for happy events, but by the same token, funerals should be avoided. - 先負 (Senpu/Sakimake)

It is best to act calmly on this day. The morning is unlucky, but the afternoon is lucky. Here the kanji mean “first lose.” - 仏滅 (Butsumetsu)

Generally inauspicious, although it is fine to conduct funerals and Buddhist rites. The name literally means “Buddha’s death.” - 大安 (Taian)

Generally auspicious, meaning “great peace.” Especially good for weddings. - 赤口 (Shakkō/Shaku)

An unlucky day, particularly for celebrations. Only noontime is considered propitious. The name means “red mouth”; the color red is associated with blood and fire, so blades and sources of fire should be avoided.

(Banner photo © Pixta.)