Yanagita Kunio: Master of Japanese Folklore and Legends

History Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Ordinary People and Mystical Experiences

While working as a top government bureaucrat, Yanagita Kunio (1875–1962) conducted research and dedicated himself to establishing folklore studies as a new academic field in Japan, writing many books. His works were underpinned by the belief that Japanese history was made not by famous “great men,” but by ordinary people living their daily lives.

He was born in 1875 in what is now Fukusaki, Hyōgo Prefecture, to a doctor, Matsuoka Misao, and his wife Take. His four brothers who survived to adulthood also achieved success in various careers, including his eldest brother Matsuoka Kanae, who became a doctor and politician. He took on the name Yanagita when he was adopted into the family as an heir in 1901, and married a daughter of the family three years later.

In his 1954 memoir Seventy Years in My Hometown, Yanagita recalled his childhood days. While we now talk about “missing persons” when someone vanishes, in the past people thought that women and children were carried away by mountain deities (kami) or the creatures known as tengu in a phenomenon known as a kamikakushi. As a two-year-old, Yanagita woke up from a nap and repeatedly asked his heavily pregnant mother Take, “Do I have an aunt in Kobe?” His irritated mother apparently replied, “Yes, you do.” Then Yanagita left the house, and he was eventually discovered four kilometers away by the young couple who lived next door.

If they had not found him then, Yanagita says, “I’m sure I would never have been heard of again.” He felt he was close to experiencing a kamikakushi. Yanagita believed his temperament made him susceptible to extraordinary happenings.

When he was 12, he moved to Fukawa in what is now Tone, Ibaraki, where his brother Kanae had opened a clinic. One day, he opened the door of a local family’s hokora miniature shrine and found a beautiful soapstone bead inside. With a strange sense of exhilaration, he looked up at the blue sky to see dozens of stars. Just then, the cry of a bulbul made him feel like he had been restored to life. If he had not heard it, he says that he may have lost his mind.

An elderly woman in that family had rubbed the bead while she was recovering from a stroke, and they later enshrined it as a household deity. Yanagita valued such mystical experiences and seems to have had a latent desire to understand them, which led him to his research.

Family Trouble in “Japan’s Smallest House”

In Seventy Years in My Hometown, Yanagita presents two episodes that motivated him to develop folklore studies.

His mother Take was an expert mediator in disputes between married couples in the neighborhood. When Okō, the woman from a neighborhood inn called Ebisuya, regularly came to complain indignantly about arguments with her husband, Take soothed her with words and sent her away smiling. However, after Kanae married a local woman and they all lived together, there were endless quarrels between Take and her daughter-in-law, who eventually went back to her parents’ house, leaving Kanae’s life in disarray. Yanagita thought that the cause of his brother’s misfortune was the tiny house they lived in in Fukusaki, which he described as “Japan’s smallest”—it still stands today in the town’s Tsujikawayama Park. This was too cramped for two families to live together comfortably. Yanagita says the house’s size and the two women’s disputes were at the base of his desire to pursue folklore studies, as believed this was also a field in which one could consider problems related to family.

Yanagita Kunio’s childhood home in Fukusaki, Hyōgo Prefecture. (© Hyōgo Tourism Bureau)

In 1884, the Matsuoka family sold the house so that Kanae could become a doctor, and they moved to Take’s hometown in what is now Kasai in Hyōgo. The following year, when Yanagita was nine, he saw the miserable spectacle of starvation. Prominent merchant families built stoves and distributed rice porridge for a whole month to people who came carrying their earthenware pots.

His belief that this kind of tragedy should not keep happening motivated him to major in agricultural administration at Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo). He also said that his feeling that famine should be eradicated led him to folklore studies.

Strange Stories from Tōno

After graduating, Yanagita joined the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce in 1900, working as an elite bureaucrat until 1919, when he resigned as chief secretary of the House of Peers. As part of his work, he traveled across Japan for lectures and inspections, and was astonished in 1908 to discover on visiting the village of Shiiba in Miyazaki Prefecture that boar hunting and slash-and-burn farming were still being practiced there. Japan had rapidly modernized after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, but development was not uniform in this hilly island country, and traditional ways of living remained.

That year, he was introduced to an aspiring young writer called Sasaki Kizen from Tōno in Iwate Prefecture. He listened to and wrote down Sasaki’s strange stories from his hometown of kami and yōkai (supernatural creatures) that had been passed down in local families. These must have chimed with his affinity for the weird. Yanagita organized them into 119 tales, which he published in 1910 as The Legends of Tōno.

A view of the Tōno Basin in Iwate. (© Pixta)

Tōno is a small basin in the southern Kitakami Mountains. According to legend, it was a lake in ancient times, with female deities residing on each of three surrounding mountains. During the Edo period (1603–1868), it became a castle town ruled by the Nanbu clan, prospering through the large crowds that gathered on market days. Traders brought in agricultural products and seafood on horseback, and apparently also mysterious stories to share.

The 119 tales present a land home to both people and a range of supernatural beings, including mountain and household deities, wild mountain men and women, and creatures like kappa and tengu. Among them are the zashiki warashi, child spirits who live in old houses and are believed to affect the residents’ fortunes. There is also Oshirasama, a deity strongly associated with Tōno, who is revered as a kami of silkworm culture; she has her origins in the story of a marriage between a horse and a farmer’s daughter.

In people’s homes, Oshirasama is typically represented by two dolls made of mulberry wood about 30 centimeters high. One is carved with a horse’s head and one with that of a girl. They would be taken out of a box during festivals and draped with cloth garments before worship. The photograph shows a pair of Oshirasama dolls worshipped as a silk culture deity at a residence in Rikuzentakata, Iwate. (© Iwate Prefectural Museum)

Meetings with the Dead

The Legends of Tōno also includes many stories of ghosts, as the line between life and death was blurred, and the dead were believed to remain close to the living.

For example, people may meet again with others they had once known. In one story, a man named Kikuchi Matsunojō struggles for breath after getting typhoid, and his soul departs from his body and travels toward his family temple of Kiseiin. When he enters as a soul within the gate, he has a pleasant feeling on seeing crimson poppies in bloom. In the midst of the flowers, his father stands and says to him, “Are you here too?” He makes some kind of reply and continues on to where his son, who died young, says to him, “Daddy, are you here too?” Kikuchi approaches closer, asking “Is this where you’ve been?” but his son says, “You can’t come now.” When he hears someone calling his name from around the gate, Kikuchi reluctantly goes back and returns to his senses. His gathered relatives had poured water on him to bring him away from the brink of death. In this account of a near-death experience, the person revived describes his soul’s journey.

Another story tells of a man called Fukuji who marries into a family in the coastal town of Tanohama (now Yamada, Iwate). His wife and all but two of his children are killed in a tsunami, and he lives with the surviving children in a hut built where his former residence used to be. One year after the disaster, on a moonlit night in early summer, he gets up to relieve himself and sees a man and woman approaching through the mist, realizing that the woman is his dead wife. The man she is with had also died in the tsunami, and is someone he heard that she was close to before her marriage. She says to Fukuji, “I’m married to this man now,” to which he asks, “But don’t you care about our children?” She turns pale and bursts into tears. In disbelief that he is talking with the dead, Fukuji despondently looks down at his feet, and the couple moves quickly away. He follows them, but then accepts that they are indeed dead. In the morning, he returns to his hut, and suffers from a long sickness.

The disaster in this tragedy was the devastating 1896 Sanriku tsunami. We see the wife expressing her wish to make her own choices as an independent woman, and Fukuji encouraging her to realize that she was a mother, but having encountered his wife’s ghost, he eventually accepts that she has passed on and resolves to live his own life. This can be read as a story about the heart’s recovery, dealing with how to get through grief.

Recognized as a Classic

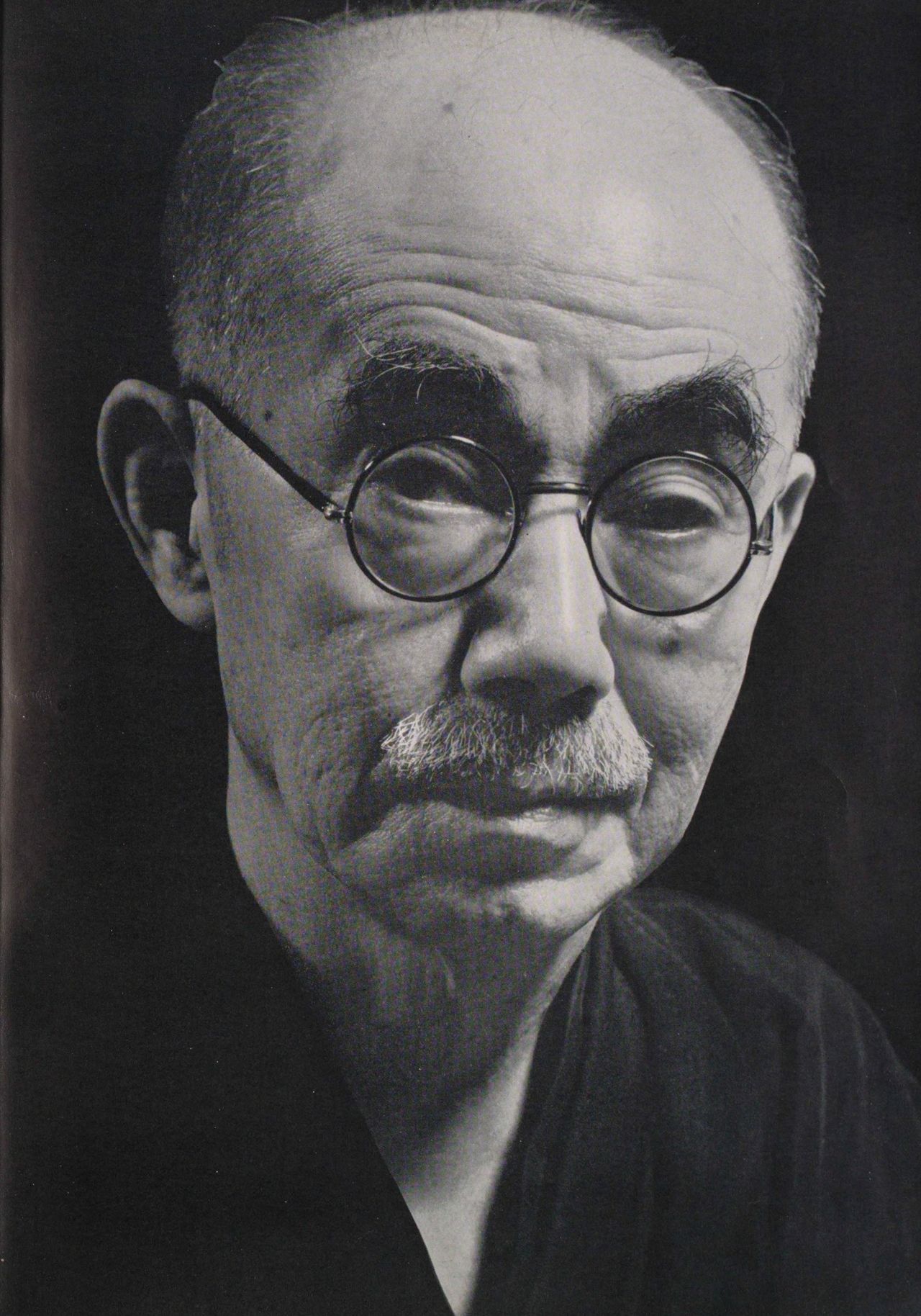

Yanagita Kunio in front of his house in Setagaya, Tokyo, in October 1956. (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

In the preface to The Legends of Tōno, Yanagita said that the stories of mountain deities and people were not just folk tales or fabrications, but that they were events that actually took place. It is true that the stories carefully detail when and where they happened and who was involved, with many real people appearing. Some describe how families killed a newborn kappa child, or how a family fell into ruin after the departure of a zashiki warashi. These stories can be linked with the practice of infanticide (for reasons including limiting family size in impoverished times), which was a topic difficult to discuss openly.

With a self-published print run of just 350, The Legends of Tōno initially met with a disappointing reception. Only authors like Izumi Kyōka and Akutagawa Ryūnosuke showed their appreciation at first, although with the establishment of folklore studies—historical research based on folk traditions—it came to be regarded as a classic. Researchers are still finding new relevance today in its records of how people faced up to and came through epidemics and disasters.

Yanagita also wrote in the preface that he hoped the stories would “make the lowlanders shudder.” By the “lowlanders” (heichijin), he presumably meant Tokyoites who took civilization for granted. More than a century later, and over 60 years since Yanagita’s death in 1962, the traditional ways of life he considered in his folklore studies have successively vanished. The Legends of Tōno meanwhile, has found foreign readers through publication in translation in languages including English, Chinese, and Korean, and it has also recently been adapted to manga. His 1956 collection Discussions of Yōkai also features many varieties of yōkai that have become hugely popular, inspiring burgeoning research. Yanagita’s folklore works continue to find new readers both in Japan and around the world.

Referenced Works

Works by Yanagita Kunio mentioned in the text:

- Kokyō shichijūnen (Seventy Years in My Hometown) has no English translation

- Tōno monogatari is translated as The Legends of Tōno by Ronald A. Morse

- Yōkai dangi (Discussions of Yōkai) has no English translation

(Originally published in Japanese on November 21, 2025. Banner image combines photographs of Yanagita Kunio [courtesy the National Diet Library] and the Tōno Basin [© Pixta].)