Manga as a Window on Japanese Culture

Furuta Oribe: A Samurai Life Devoted to Zen and Tea

Culture History Manga- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Warrior Who Lived the Way of Tea

The centralization of power in Japan began in the seventh century, leading to the establishment of a system of nationwide government by the aristocracy under the imperial court by the start of the eighth century.

But it was not long until samurai started to emerge as a new political force. In the twelfth century, under the leadership of the shōgun, they were able to consolidate power in the form of the shogunate, which left nominal authority with the emperor but wielded actual military power through the figure of the shōgun. This system of power materialized during Japan’s medieval period, but later, disturbances became widespread, leading to the Warring States period (1467–1568), when tiny fiefdoms abounded.

Japan is an island country, surrounded by sea on all sides. It has been characterized by low movement of ethnic groups, creating a society with strong heredity tendencies (even Japan’s current Diet is composed of about 30% hereditary members). But the Warring States period was a time of meritocracy and success through strength, which saw the nationwide emergence of feudal lords, or daimyō, from among the samurai class.

But as with feudal lords in medieval Europe, they required not only the strength of a lion, but also the cunning of a fox. Daimyō in medieval Japan were not only brave; many were well-versed in what we today might call “soft power.”

A key cultural trend that flourished in their ranks was the culture of tea. Yamada Yoshihiro’s manga Hyōge mono (styled as Hyouge Mono: Tea for Universe, Tea for Life in some English renderings) is a historical narrative based on the life of Furuta Oribe, a samurai who lived in an age of war while also being a tea master who dedicated his life to sadō, the way of tea. It won the Grand Prize in the fourteenth Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prizes, presented in 2010, and was adapted into an anime in 2011.

The Museum of Furuta Oribe opened in Kyoto in 2014. It displays tea utensils, artworks, and historical materials connected to Oribe. (© Kyōdō)

In the style of tea with which he became enamored, the host prepares the drink in order to entertain a guest, using prescribed utensils and techniques. But it was more than a matter of manners.

During the Meiji era (1868–1912), Okakura Kakuzō (also known as Okakura Tenshin), curator of the Department of Japanese and Chinese Art at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, wrote The Book of Tea to introduce the pastime to people outside of Japan. In his book, he stated: “Teaism is a cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence.”

Essentially, tea, while being the practice of tea drinking, an activity performed regularly, is also a ceremony that reveals universal beauty and is linked to cosmic principles. Okakura stated that its inner mysteries lie in the adoration of the imperfect.

Owing to its detailed etiquette, people tend to think of tea as somewhat unapproachable, but in recent years, facilities have sprung up that make it easier for youth and non-Japanese people to learn. Taken at the Nakamura Chaho, Matsue, Shimane Prefecture. (© Jiji)

The Japanese word for tea, sadō, contains the element dō also used in terms like jūdō and bushidō. It is sometimes translated as “way” in English. The final destination of the “way” is a spiritual summit comparable with enlightenment in Zen Buddhism. In fact, the most renowned practitioner of sadō in Japanese history, Sen no Rikyū (1522–91), also devoted himself to Zen.

Tea became a popular pastime among samurai in the Warring States period, but its popularity also led to a fascination for the vessels used for tea drinking. A bewildering aspect of this is the value accorded to these objects, but this also relates to the Zen origins of the practice, which saw beauty and cosmic truths in the ordinary details. It would be mistaken to expect that a tea utensil was necessarily valuable because it was shiny, ornate, or decorated with gemstones. Confusingly, a chipped tea bowl that dropped on the earthen floor of a fisher’s kitchen could be considered a rare masterpiece.

Thus, appraisal of tea implements is only possible by people who are recognized to have the skills to determine their value. Sen no Rikyū was considered to have the keenest such discernment of his time.

The main protagonist of Hyōge mono, Furuta Oribe, was Sen no Rikyū’s leading disciple. After his teacher’s death, Oribe was considered the greatest tea master alive.

The work was a part of the fourth Niigata Anime and Manga Festival (Gata Fes), held in 2013. Various artists were involved in collaborations. (© Niigata Anime and Manga Festival Executive Committee)

To Live in Beauty or Battle

In the story, Oribe’s character struggles with the choice between a life dedicated to his pastime or one steeped in battle. Initially, he was only a commissioned officer, but still, he possessed a genuine aesthetic sense. He was in no way incompetent as a warrior, and had been willing to sacrifice his life on the battlefield as an envoy at one point. His one weakness was that, even in a pinch, he could not resist the allure of tea utensils.

Oda Nobunaga was his lord, a daimyō of unique stature, skilled in economics, politics, and warfare. He promoted those of talent regardless of their background. He also possessed a keen sense of beauty, and was able to appreciate objects brought to Japan by Western traders and missionaries.

But he is also known for his severe character, famously stamping out religious groups he considered hostile and ruthlessly purging incompetent subordinates. In the same way that Swiss cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt considered Frederick II (“the Great”) to be “the first modern man on the throne,” in historical terms, Nobunaga is a controversial personality.

Incidentally, in many East Asian markets, he is known in popular culture as the main character in a video game, Nobunaga no yabō (Nobunaga’s Ambition).

Nobunaga aimed to reunite a divided Japan, but he was assassinated by his subordinate Akechi Mitsuhide. His project was inherited by another subordinate, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who quickly succeeded in uniting Japan, after which he used Rikyū to help inaugurate a golden age of tea.

Up to this point, Hyōge mono is based on historical fact, but beyond that, it is a creation of the author’s imagination.

Actually, it was Hideyoshi, conspiring with Rikyū, who encouraged Akechi Mitsuhide to embark upon the coup d’état. Hideyoshi secretly wanted to kill Nobunaga at his own hand. The background to his conspiracy lay in their opposing aesthetic tastes: Oda’s grandiose world of beauty was incompatible with Rikyū’s extreme minimalism and admiration of black.

In the 1980s, Japanese fashion designer Kawakubo Rei caused a sensation with her Comme des Garçons label, which launched black Japanese clothing into the colorful world of fashion. This aesthetic appreciation of black is part of the Japanese wabi sabi tradition, which Rikyū lived and breathed.

This is the reason he took part in the plot to obliterate Nobunaga, but his successor, Hideyoshi, soon took up Nobunaga’s extravagant aesthetics as his own. Hideyoshi became antagonistic toward Rikyū, and saw no option but to kill him.

Furuta Oribe was the only person who knew of Hideyoshi’s anguish. After Hideyoshi’s death, Tokugawa Ieyasu gained control, and was appointed shōgun by the emperor. The Warring States period drew to a close, and the Tokugawa reigned supreme. But at the same time, Furuta Oribe began plotting his own conspiracy, with a very small group of associates. This was also due to his antipathy toward Tokugawa’s artistic taste.

The Sagawa Art Museum in Moriyama, Shiga Prefecture, staged an exhibition in 2015 marking the 400th anniversary of the death of Furuta Oribe, accompanied by Hyōge mono–themed advertising in JR trains throughout the Kansai area. (© Sagawa Art Museum)

A Tale of Sensibility Still Relevant Today

Hyōge mono is a term to describe a jovial person. But it does not refer to straightforward humor that makes others laugh. Rather, it alludes to more complex tastes. In fact, such a modern sense of humor first emerged during the time of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi.

For example, Nobunaga erected a giant rock in his castle and instructed his subordinates to pay their respects to it as though it were him. No doubt Nobunaga struggled to keep a straight face as he watched his subordinates earnestly praying to the rock.

When Rikyū’s disciple sent chicken meat when he was ill, he wrote back, saying “Could you please send money instead of chicken?” Historian Hongō Kazuto has suggested that this was the maestro’s unique sense of humor.

Furuta Oribe, as depicted in Hyōge mono, is also fond of such bewildering expressions of wit. But alas, the end of the Warring States period was also the end of the time when expressions of extreme individualism were tolerated—Tokugawa Ieyasu’ss seriousness and stability came to color his era. With this wave of change, Furuta Oribe chose, at the end of his days, to use his very life as a way to express his sense of beauty. Leaving behind a once-in-a-lifetime masterpiece, his story drew to a close.

Tokugawa chose to establish his government in Edo (modern day Tokyo), and restricted foreign intercourse and innovation. In his world, the adoration of imperfection came to an end, and orderliness became the main focus in society. In exchange for innovation, Japan obtained stability, which it successfully maintained until 1853, when US Commodore Matthew C. Perry came to Japan demanding that it open its doors.

Similarly, in the reality of our modern society, the stability of the twentieth century feels like a thing of the distant past. Today, we live in turbulent times than more closely resemble the era of the Warring States. We can therefore empathize with the fortunes of Furuta Oribe, who lived according to his own peculiar tastes in a world of turmoil.

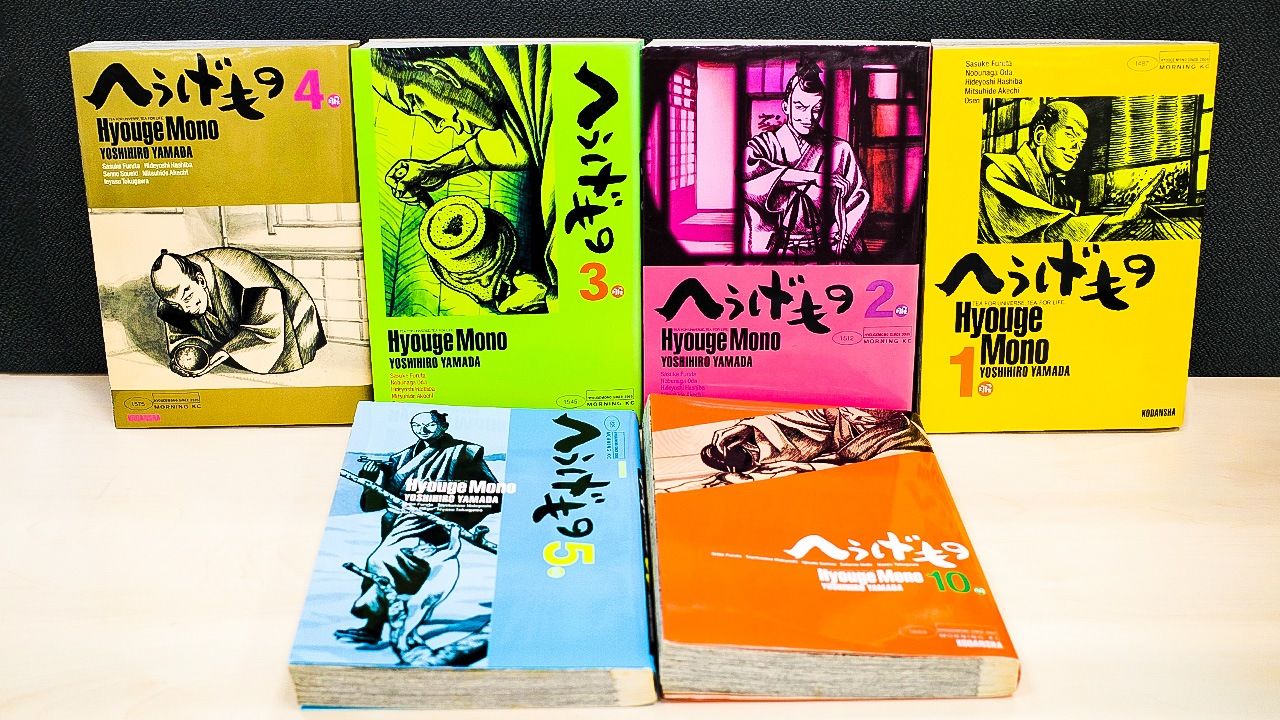

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Hyōge mono first appeared as a series in Kodansha’s weekly manga magazine Mōningu (Morning), from 2005 to 2017, and was also released, with a distinctive cover, as a stand-alone series of 25 books. It was adapted as an anime series for NHK-BS from 2011 to 2012. © Nippon.com.)

tea ceremony Sen no rikyu tea Zen Toyotomi Hideyoshi Oda Nobunaga Tokugawa Ieyasu samurai Manga and Anime in Japan