Masked Bringers of Fortune: Japan’s Divine Visit Tradition

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

UNESCO Recognition

On November 29, 2018, a set of 10 Japanese ritual visits of deities in masks and costumes was added to the UNESCO representative list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

One of these—the toshidon visitors of the Koshikijima islands in Satsumasendai, Kagoshima Prefecture—had already been inscribed individually to the list in 2009, but Japan successfully made the case to supplement it with nine further similar customs. They are collectively included as “social practices, rituals, and festive events,” one of the list’s five categories.

Turning Points of the Year

The divine visitors, or raihōshin, set apart from the ordinary residents through their masks and clothes, are seen as traveling from the outside world to call on settlements and individual houses. These are not the kinds of gods found in religious scriptures; instead, they are the manifestations of folk beliefs passed down from generation to generation. They only appear on set days each year, based on the specific local tradition.

These days are typically at important turning points of the calendar, such as New Year. For example, the toshidon make their visits on New Year’s Eve, the suneka on January 15 (Koshōgatsu, or “Little New Year”), and the amamehagi in early January or at Setsubun.

Obon, the summer festival when the spirits of ancestors are said to return to the world, is another such period. The boze of the island of Akusekijima appear at this time, while the mendon of Iōtō (Iwo Jima) come as summer transitions into autumn. Okinawa’s pāntu may arrive either around this time or shortly before New Year in the old lunar calendar.

The amamehagi of Noto. (Courtesy Haga Library)

In Buddhist monk Yoshida Kenkō’s classic Tsurezuregusa (trans. Essays in Idleness), written around 1330, he describes how in Kyoto on New Year’s Eve, people light pine torches and rush about knocking on doors until late at night. Although this passage in the nineteenth section of the work does not explain the reason for the activity, it could be said to be a kind of divine visit ritual.

An entry on the Tsukuba area in the fudoki, or report on local conditions, for Hitachi province compiled in the early Nara Period (710–94) includes a story about an ancestral kami (god), which pays visits on the evening of a harvest festival to Mounts Fuji and Tsukuba. The Fuji kami refuses it lodging, but the Tsukuba kami gladly provides hospitality. The ancestral deity responds by making snow forever fall on Mount Fuji, so nobody can climb it, while people gather to sing dance, and feast on Mount Tsukuba.

This story shows that the belief in divine visits has existed since ancient times. It also emphasizes the importance of properly welcoming the deities, as local residents do for the namahage, toshidon, and others today.

Also note that these historical examples take place at New Year and the harvest period, as with their UNESCO-listed counterparts.

Visitors Across Japan

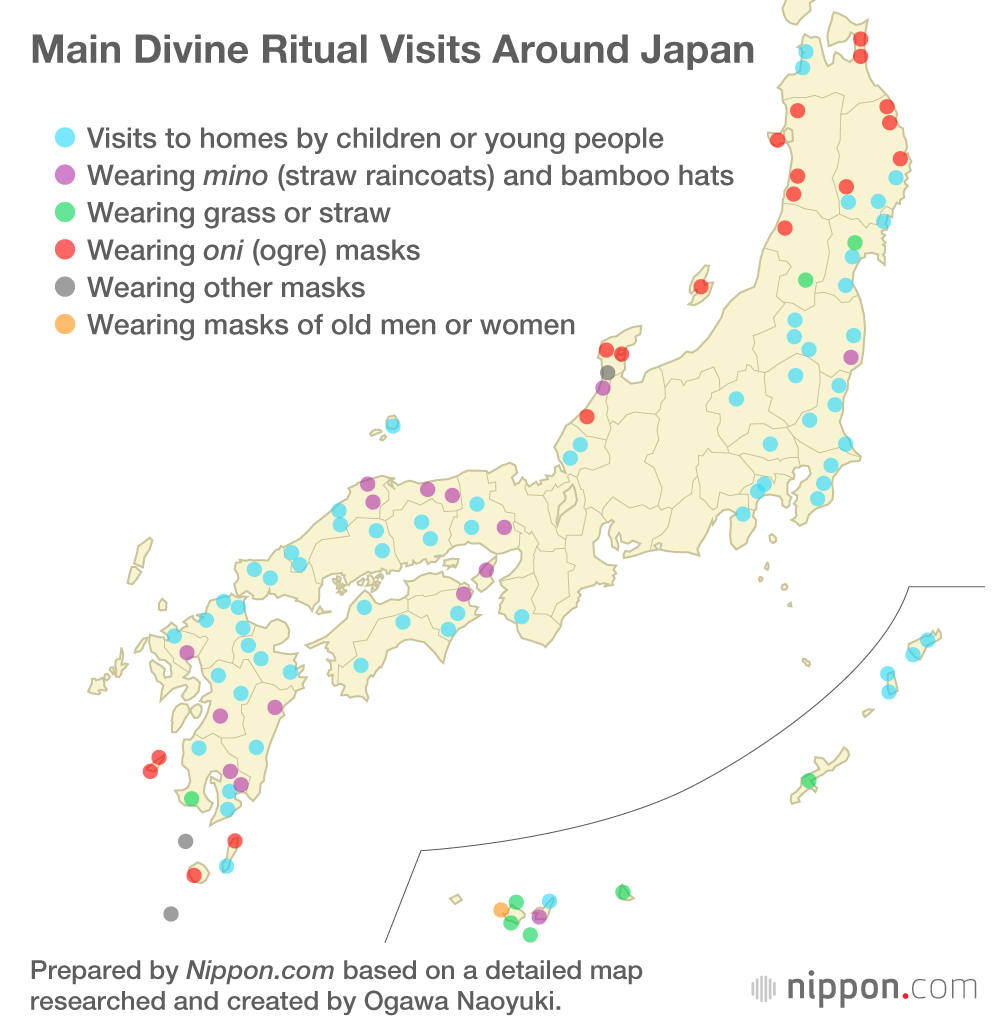

Japan has more than just the 10 divine visit rituals recognized by UNESCO, particularly when past customs are included, as this was once a standard folk practice. Excluding Hokkaidō, where there is no evidence of the native Ainu performing such rituals, versions are found across the whole country. Customs and festivals are especially prevalent in Tōhoku, Kyūshū, and Okinawa.

From northern Tōhoku along Honshū’s west coast to Hokuriku, there are visitors with similar names: namahage, amahage, and amamehagi. Names like kasedori can be found from southern Tōhoku to Kantō, as well as in Kyūshū. There are also names based on the sound of knocking on a door, such as hotohoto, kotokoto, and patapata, from western Kansai to northern Kyūshū, as well as some parts of Kantō.

Some do not wear masks or costumes, instead slipping into houses unseen to leave miniature wooden agricultural tools and take offerings of mochi rice cake or money.

The kasedori of Saga Prefecture. (Courtesy Haga Library)

Bringers of Luck, Dispellers of Misfortune

When the toshidon pay their visit on New Year’s Eve, they ask about the children’s behavior in the houses they visit, and praise, scold, or admonish them. Finally, they hang a heavy mochi on each child’s back, which is said to make them one year older. This is a traditional equivalent to the small money gift known as otoshidama that Japanese children receive at New Year, and is intended to give them the strength to live through another year.

The namahage, amamehagi, and amahagi carry knives—now only models—thought traditionally to have been for peeling off fire-blisters on hands and feet that strayed too close to the irori sunken hearth. These visitors also chide children for their laziness and teach them the error of their ways. The kase in the name of the kasedori, meanwhile, is thought to have a meaning related to eczema and other skin problems. These examples show that one role of the divine visitors is to drive away illness at New Year.

The paantu of Miyakojima, Okinawa, are covered with mud taken from a sacred spring, which they in turn smear on residents and the walls of houses in the settlement. This is said to chase away misfortune and bring good luck. The mendon carry branches to hit others with and dispel evil spirits. The boze carry similar sticks tipped with red mud, said to drive off demons and make women fertile.

The mendon of Iwo Jima. (Courtesy Haga Library)

As they travel from house to house, the mayunganashi of Ishigakijima, Okinawa, chant about agricultural methods and offer blessings.

The mayunganashi of Ishigakijima, Okinawa. (Courtesy Haga Library)

While there are many kinds of raihōshin, they all share knowledge and the strength to live within communities, while dispelling bad luck. It was believed that they allowed people to continue to lead healthy and fulfilling lives.

Voyaging from the Spirit World

The raihōshin are like other Japanese spirits that travel to the human world during festival periods before returning again to the spirit world. However, ancestors greeted by mukaebi (welcoming fires) at Obon and the toshigami or New Year gods met with the kadomatsu (gateway pines) set out by households are invited spirits that have no form. By contrast, the raihōshin are seen as choosing to visit themselves, and they have a clear physical presence.

Their costumes represent the Japanese image of gods. Bamboo hats and mino raincoats are the typical garb of travelers on long journeys, while the masks of oni or other creatures highlight their separate existence from humans. Ancient Japanese texts like the Man’yōshū poetry collection called the spirit world the Tokoyo. It was imagined as being beyond the sea, in the mountains, in the middle of the forest, or even in the sky.

The folklorist Orikuchi Shinobu (1887–1953) dubbed the divine visitors marebito and developed a cultural theory that their chants later developed into literature and their movements into performing arts.

Yet, we must not forget that this is not a solely Japanese phenomenon. To give just a few examples, there are the Krampus, which visits Germany and Austria on December 5; the kläuse tradition on New Year’s Eve in the Swiss village of Urnäsch; and the manghao of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in southern China, which appear at Chinese New Year.

The Raihōshin (Ritual Visits of Deities) Inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

| Toshidon (Satsumasendai, Kagoshima Prefecture) | New Year’s Eve | Masks, mino (straw raincoats), palm leaves |

| Suneka (Ōfunato, Iwate Prefecture) | Evening of January 15 | Oni (ogre) or horse masks; mino, furs, or rice sacks |

| Namahage (Oga, Akita Prefecture) | New Year’s Eve (Formerly January 15) | Oni masks, mino |

| Amahage (Yuza, Yamagata Prefecture) | New Year’s Eve | Oni masks, mino |

| Mizukaburi (Tome, Miyagi Prefecture) | February, the first Day of the Horse of the traditional calendar. | Faces smeared with ink, shimenawa (sacred ropes) around shoulders, mino |

| Amamehagi (Wajima and Noto, Ishikawa Prefecture) | Evening during Shōgatsu (early January) and Setsubun | Tengu (long-nosed goblin), pug-nosed, or other masks; mino |

| Kasedori (Saga, Saga Prefecture) | Evening of New Year’s Day of the traditional calendar. | Bamboo hats, tenugui (cotton hand towels) around faces, mino. |

| Mendon (Mishima, Kagoshima Prefecture) | The first to the second day of the eighth month of the traditional calendar | Basket masks, mino. |

| Boze (Akusekijima, Kagoshima Prefecture) | The sixteenth day of the seventh month of the traditional calendar (the last day of Obon). | Faces smeared with red clay or ink, palm leaves wrapped around bodies. |

| Paantu (Miyakojima, Okinawa) | Early in the ninth month or on the final Day of the Ox in the twelfth month of the traditional calendar. | Masks and vines around the body smeared with mud. |

Chart created by Ogawa Naoyuki.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 28, 2018. Banner photo: The amamehagi of Noto. Courtesy Haga Library.)