A Look Inside the Bathhouses of Edo

History Culture Lifestyle Art- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Bathing Tradition

The first sentō (public bathhouse) appeared in Edo in 1591. According to the record Sozoro monogatari (trans. Tales That Come to Mind), a man named Ise Yoichi opened this new establishment in what is now Ōtemachi, Chiyoda, in the heart of Tokyo’s office district.

The heat and steam were such that it felt suffocating and was hard to speak or open one’s eyes. However, Edoites soon grew used to public bathhouses—perhaps the temperature was adjusted—and they became a part of city life in the Edo period.

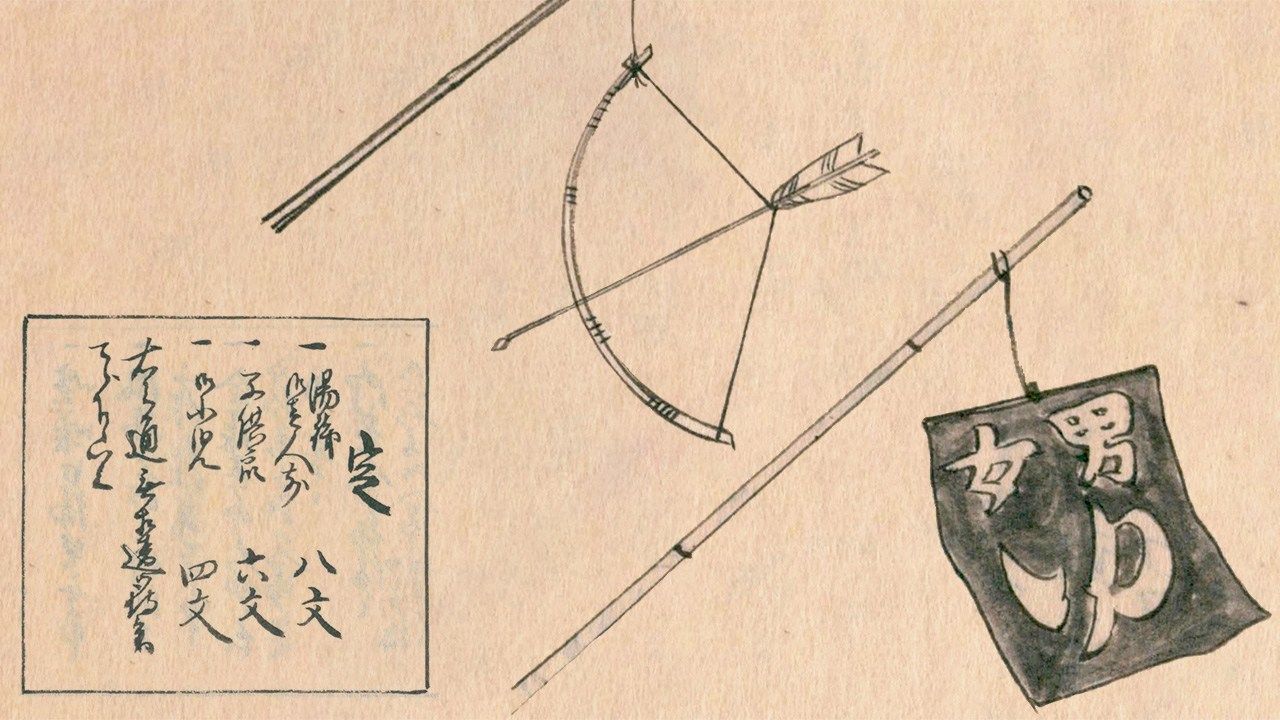

The bathhouses sometimes had punning signs showing a bow and arrow, as “fire an arrow from your bow” (yumi iru) sounded like “enter the bath” (yu ni iru). These grew less common in the later part of the Edo period. From around 1830, it became standard to display navy blue fabric with the characters for “men,” “women,” and “bath” on it.

The entrance fee was typically 10 mon for an adult (1 mon is equivalent to around ¥12 today). As part of the Tenpō reforms initiated by the shogunate from 1841, fees were, however, fixed at 8 mon for adults, 6 for children, and 4 for infants. (These prices appear on the sign shown in this article’s main image.)

Kitagawa Morisada, who sketched the sign, was a keen chronicler of life in Japan’s cities during the nineteenth century. He noted that a surge in the price of firewood around 1862–63 led to the entrance charge for adults rising to 12 mon.

Many goods were becoming more expensive at the time due to the effects of the opening up of the country by the US Navy Commodore Matthew Perry. The twilight of the shogunate was also marked by bloody events like the March 24, 1860, assassination of Ii Naosuke, the shogunate’s chief minister, and the killing of a British merchant by samurai from the Satsuma domain (now Kagoshima Prefecture) in the September 14, 1862, Namamugi Incident.

Entrance fees rose further in 1865 to 16 mon and the following year to 24 mon, as political uncertainty influenced everyday costs. This is the era that Morisada chronicled.

Cramped and Dark

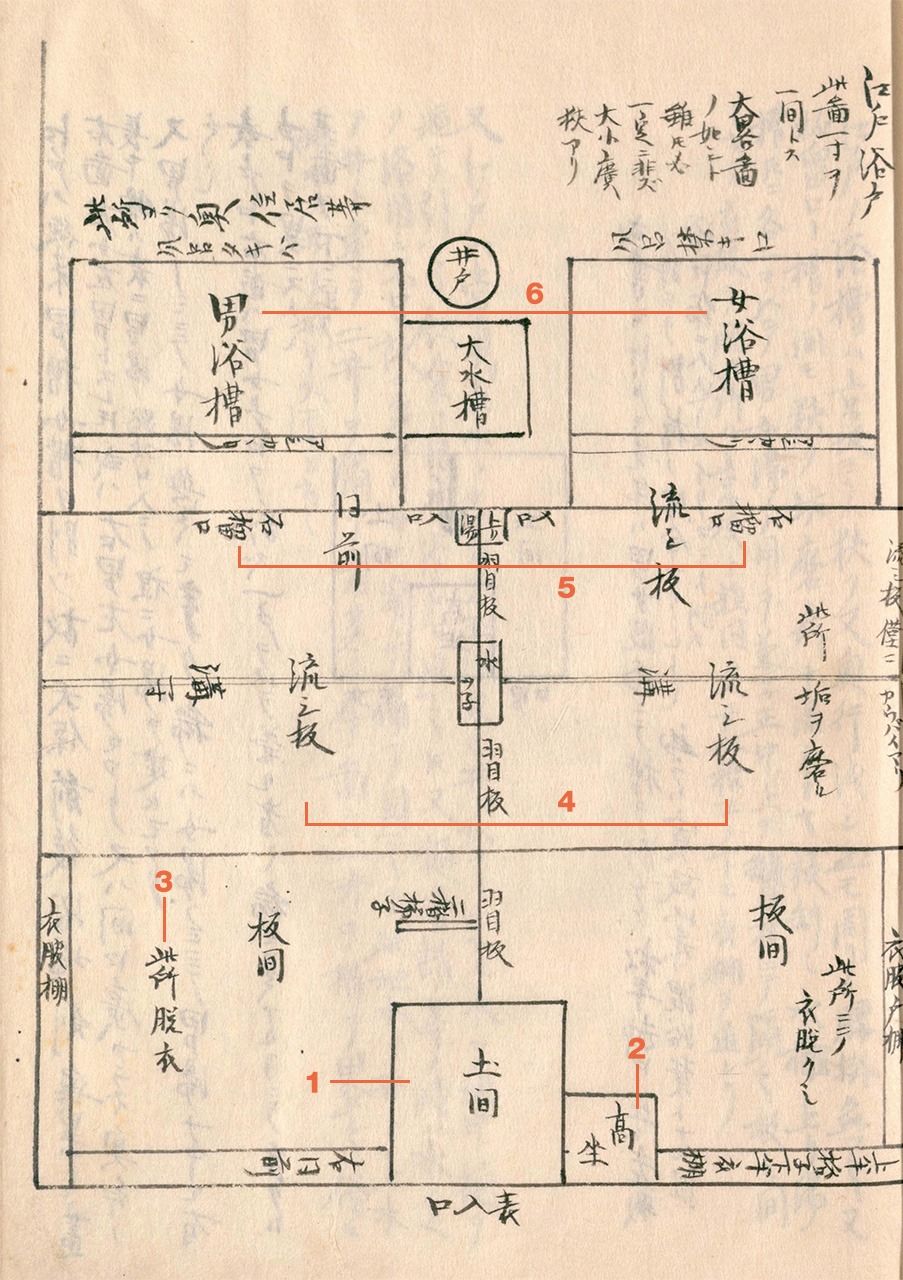

Among Morisada’s materials is a sketch of an Edo bathhouse floor plan.

A floor plan of an Edo bathhouse, indicating (1) the doma, an earthen-floored entrance space; (2) the bath attendant’s platform; (3) a changing area; (4) washing areas; (5) the zakuroguchi, entrances to the baths; and (6) the baths. From Morisada mankō (Morisada’s Sketches). (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Beyond the entrance space and attendant platform, there is a division into the bath for men on the left and that for women on the right. The layout of the changing and washing areas and baths is almost the same as for today’s bathhouses.

What is different is the zakuroguchi between the washing area and baths. The Kōjien dictionary defines zakuroguchi as Edo-period entrances to baths. They were low, so bathgoers had to stoop to pass through them. Thus, the baths felt more like separate rooms than part of the same space as the washing area.

Morisada records differences in the designs of these entrances in Osaka and Edo.

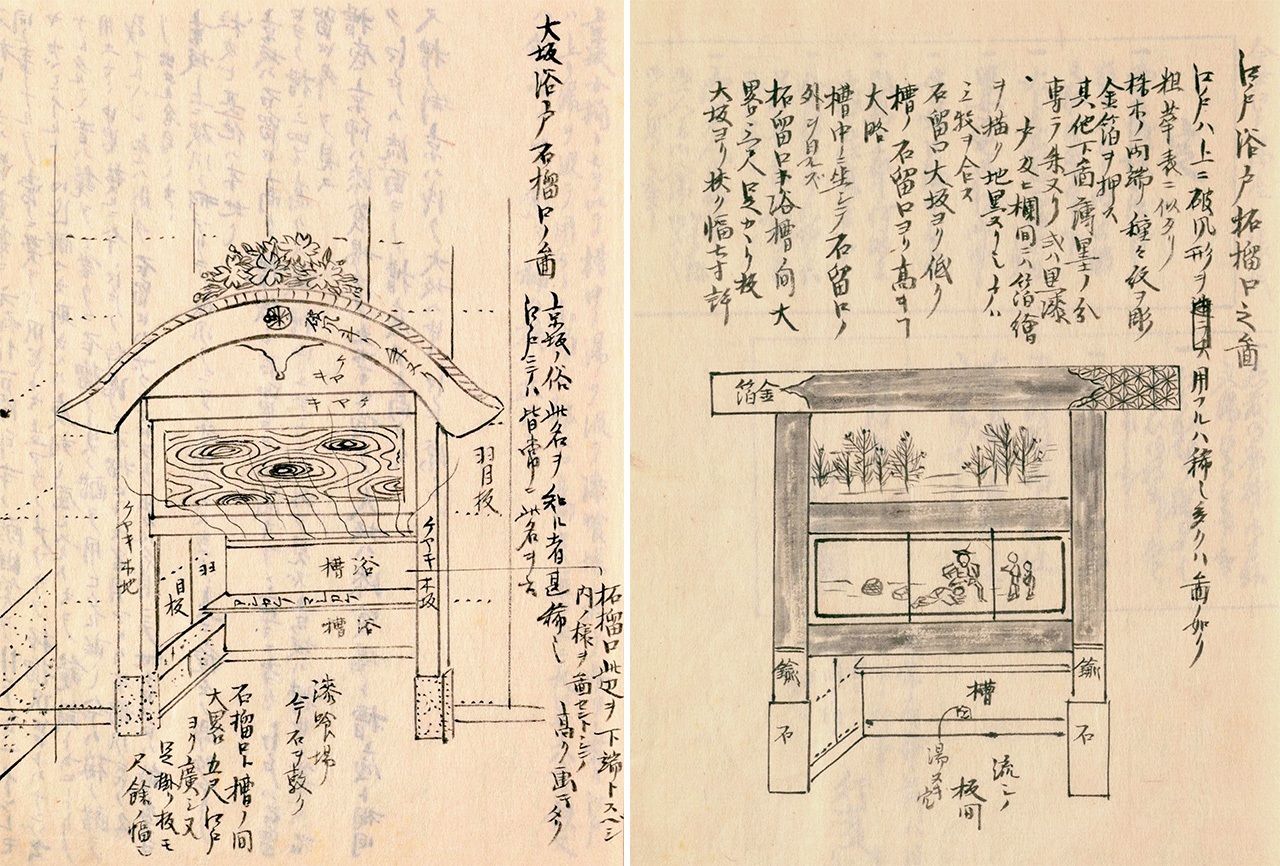

Zakuroguchi in Osaka (left) and Edo. From Morisada mankō (Morisada’s Sketches). (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Bathhouses originated in the west of Japan, so the Osaka zakuroguchi on the left represents the first version. It is extravagant, with vermilion gables and carvings of flowers. Meanwhile, the Edo entrance to the baths recalls a shrine’s torii gate.

There is also a picture above the Edo entrance with scenery and people, although the details are unclear. Today, Mount Fuji is a common feature in sentō art, but this association is thought to have caught on in the early twentieth century. Morisada makes no mention of pictures of Fuji.

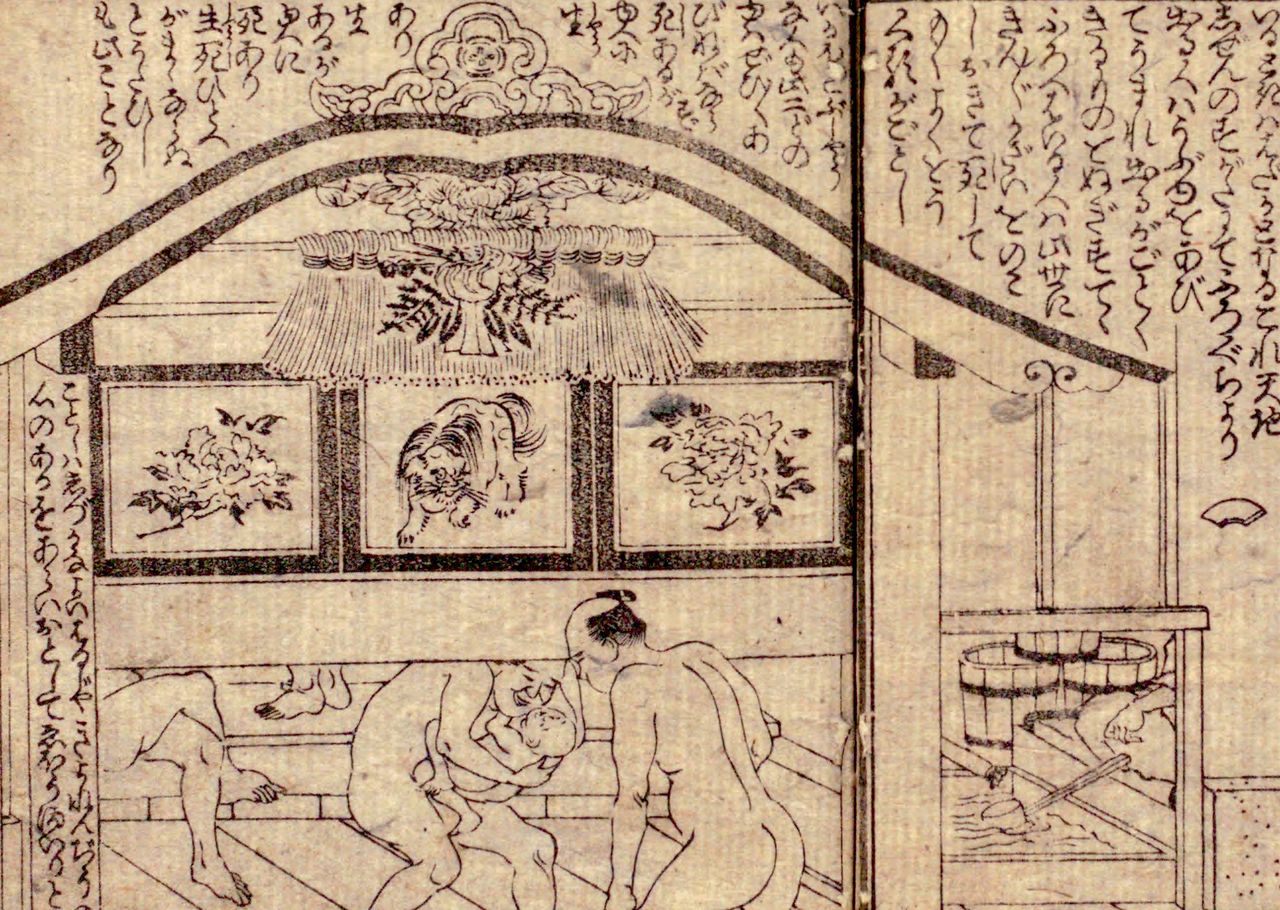

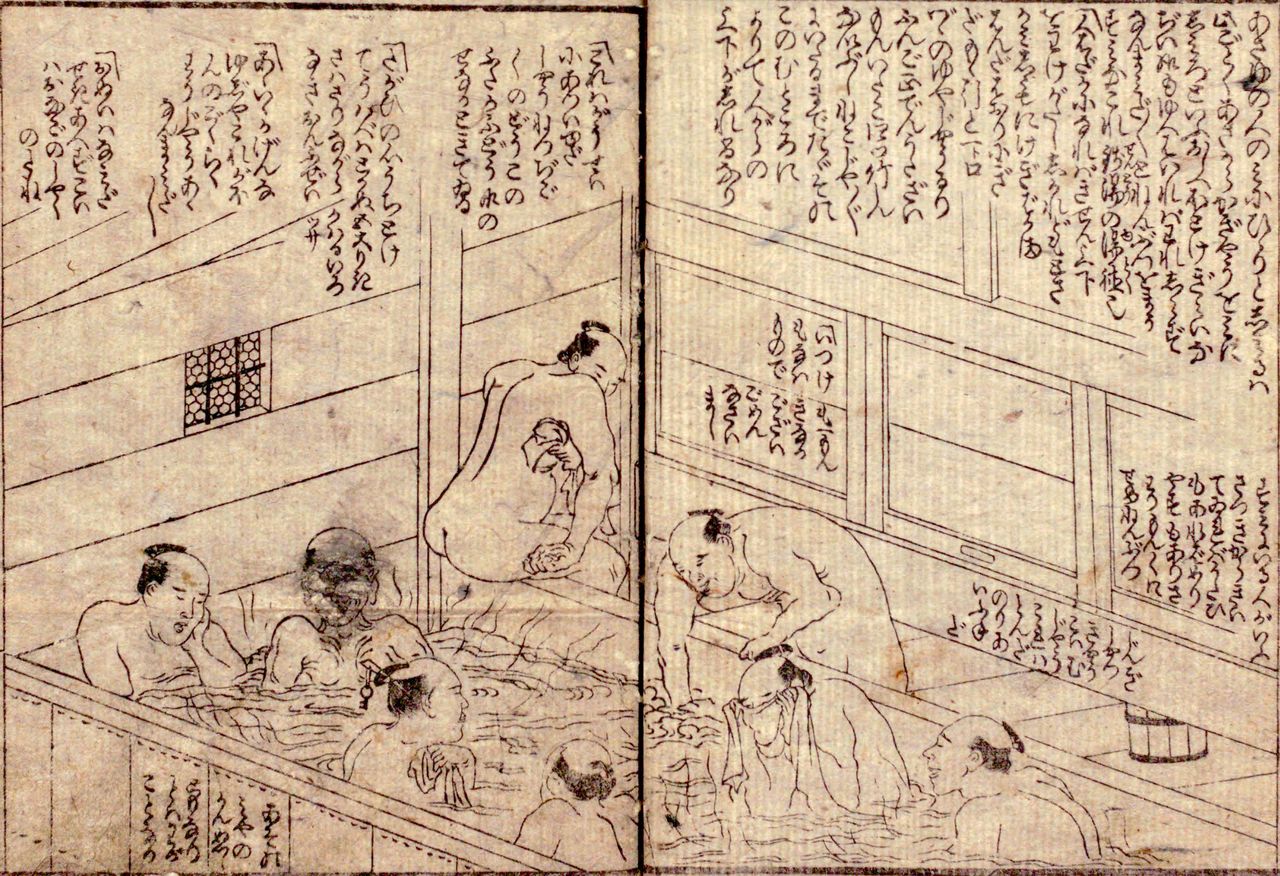

The writer Santō Kyōden, who was born around 50 years before Morisada, includes sketches of Edo bathhouses in his 1802 work Kengu irigomi sentō shinwa (Wisdom and Folly Mixed in New Tales of the Bathhouse).

The men’s bath in Santō Kyōden’s Kengu irigomi sentō shinwa (Wisdom and Folly Mixed in New Tales of the Bathhouse). The top picture shows the zakuroguchi, while the bottom picture looks down on the bathing area, with a bucket visible in the washing area. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Note the western-style gables on the zakuroguchi, showing these were still seen in Edo in the early nineteenth century. For some reason, they seem to have been replaced by the torii style 50 years later.

In any case, the bathing area was low-ceilinged, cramped, and dark. It was nothing like the open, well-lit sentō today. Nonetheless, it was a welcome place of rest for the common people of the city.

Mixed Bathing Bans

Morisada writes of reading that mixed bathing used to be normal in Edo, but that Matsudaira Sadanobu, a senior councillor of the shogunate, ordered that there should be separate baths. It is true that mixed bathing at sentō was typical through much of the Edo period.

The Kansei Reforms (1787–93) instigated by Sadanobu prohibited mixed bathing. For Sadanobu, who promoted abstinence and clamped down on recreation, men and women bathing together tended to corrupt public morals.

When he fell from power, some bathhouses apparently revived mixed bathing. However, the Tenpō reforms tightened the rules again, and baths for men and women became completely separated.

Hadakisoi hana no shōfuyu (Naked Flower Rivalry in the Women’s Bath) by Toyohara Kunichika (1868) shows an imagined women’s bathhouse scene. In the upper right, a male attendant assists with washing. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

In some rare cases of bathhouses with limited space that could not divide their bathtubs, there might be establishments for women only. In the classic rakugo story Yuyaban (The Bathhouse Attendant), a dissolute son of a merchant who is working at a sentō daydreams about disguising it as being exclusively for women and getting a good view from the attendant’s platform.

Incidentally, a picture at the temple Ryōsenji in Shizuoka Prefecture shows a mixed bath in the last years of the shogunate. It depicts a bathing area with the gables typical of Osaka and Kyoto and a mixed washing area. The Japan-US Treaty of Amity and Commerce was signed at this temple in 1858, and it is said that the picture was painted by a foreigner.

Thus, mixed bathing continued outside Edo while it was banned in the city, and the tradition remains in some parts of Japan today.

(Originally published in Japanese on May 22, 2021. Banner image from Morisada mankō [Morisada’s Sketches]. Courtesy National Diet Library.)